SampleBookclub1 - The University of Texas at Arlington

advertisement

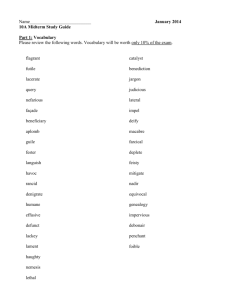

Professional Book Club Presentation LIST 5326 Fall 2007 Academic Honesty Statement I have read and understand the UTA Academic Honesty clause as follows. “Academic dishonesty is a completely unacceptable mode of conduct and will not be tolerated in any form at The University of Texas at Arlington. All persons involved in academic dishonesty will be disciplined in accordance with University regulations and procedures. Discipline may include suspension or expulsion from the University. “Academic dishonesty includes, but is not limited to, cheating, plagiarism, collusion, the submission for credit of any work or materials that are attributable in whole or in part to another person, taking an examination for another person, any act designed to give unfair advantage to a student or the attempt to commit such acts.” (Regents’ Rules and Regulations, Part One, Chapter VI, Section 3, Subsection 3.2., Subdivision 3.22).” Further, I declare that the work being submitted for this assignment is my original work (e.g., not copied from another student or copied from another source) and has not been submitted for another class. My Background • I currently teach 9th grade English I in a large urban high school. • I have taught 9th, 10th, and 12th grades over the past seven years. • I currently hold Secondary certification for English, grades 6-12, and Spanish, grades 6-12. • I am seeking the following certifications through the M.Ed. with Triple Literacy Emphasis: – Reading Specialist – Master Reading Teacher – ESL endorsement My Background: Professional Organizations I do try to stay current with professional organizations, so that I can interact with other educators and pursue conversations related to the issues facing our profession. I am currently a member of ATPE, the Association of Texas Professional Educators. I like being able to hear about different facets of education, including content areas other than English Language Arts, as ATPE is not specifically focused on one content area. In the past, I have also been a member of NCTE, the National Council of Teachers of English and TCTELA, the Texas Council of Teachers of English Language Arts. My Background: Professional Journals I do read a number of professional journals regarding education. I find that I connect with others’ ideas and find ways to adapt new strategies or suggestions for my own classroom and my own students’ needs. Plus, it is enlightening to hear the success that other educators have in the classroom. Journals that I read with frequency include English Journal, Voices from the Middle, School Library Journal, and The Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. My Background: Professional Conferences I have attended a couple of professional conferences over the past few years. I attended the New Jersey Writing Project in Texas Conference in the Spring of 2006 in San Antonio, Texas. I also attended the TCTELA conference in the Spring of 2004 in Austin, Texas. I enjoy the conference experiences because they provide ample opportunities to be creative, to learn, and to explore innovative ideas through both the individual break out sessions and the general speaker and author sessions. Plus, it is always refreshing to meet new educators and to explore the new resources that are brought out at the conferences. My Background: District Support In years past, my district has supported teacher travel and conference registration for conferences and professional development related to our content areas. However, as the money crunch has made its way to our campus and department, there have been fewer and fewer opportunities to pursue conference attendance and similar activities. Pre-AP teachers are the select few who attend miniconferences, largely because that is funded by a grant that requires, for each teacher, a set number of pre-AP conference hours each year . Reflection Statement I created the following assignment, prior to my practicum, in the fall of 2007 for LIST 5326, Teaching Language Arts in the Secondary Schools. This assignment allowed me to explore in depth an issue that is plaguing teachers across the country – reluctant male readers. This assignment demonstrates my ability to stay abreast of current research in the field of English Language Arts, while facilitating professional development ideas that will allow this research to benefit my colleagues in the classroom. Reflection Statement This assignment demonstrates my ability to reflect upon current research and its applications in the context of today’s classrooms and with today’s students. In developing this Professional Book Club Presentation, I demonstrated my understanding of IRA Standard 2 (Candidates use a wide range of instructional practices, approaches, methods, and curriculum materials to support reading and writing instruction) as I considered new and innovative instructional methods and texts to engage adolescent males with reading. Reflection Statement Additionally, in considering new approaches to engaging male readers, I demonstrated my understanding of TExES Reading Specialist Competency 006 (The reading specialist understands and applies knowledge of reading comprehension and instructional methods that promote students’ reading comprehension at the levels of early childhood through grade 12). Through the exploration of ways to get struggling male readers to interact with more texts, especially through the use of archetypes, I have been able to think more deeply about ways to encourage male readers’ comprehension of what they read by carefully selecting the texts they read. Reflection Statement Furthermore, in considering unique activities to fit with the needs of adolescent male readers, I demonstrated my understanding of TExES PPR Competency 002 (The teacher understands student diversity and knows how to plan learning experiences and design assessments that are responsive to differences among students and that promote all students’ learning) in that I explored in depth the types of texts and activities that would be more personally relevant for male students, especially those who have a reluctance to reading. Reflection Statement This Professional Book Club Presentation demonstrates my awareness of considering the needs of all readers in our classrooms, especially when there are ways to differentiate the activities and texts so that teachers can better accommodate all of the needs. It also demonstrates my recognition of the importance of exploring literature from multiple angles, specifically archetypes, as these different angles allow more readers to become involved with texts and the reading process overall. Reflection Statement As a Reading Specialist and an ESL teacher, I will work with students with varying interests in reading and Language Arts. This assignment demonstrates my understanding of the importance of sharing researchbacked practices with other teachers and staff members, so that we can all work together to meet the unique needs of our students, no matter their gender. Bibliography Brozo, W.G. (2002). To be a boy, to be a reader: Engaging teens and preteen boys in active literacy. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Information and Reviews Oregon Writing Project http://owp.uoregon.edu/2004/nussbaum/nussbaumbookreviewtwo.html This review briefly explores Brozo’s use of archetypes as a means of enticing male readers with literacy. The review highlights the fact that Brozo does provide some instructional practices, as well as a wealth of book suggestions for working with archetypes in the classroom. However, the reviewer found it difficult to completely “buy into” the use of archetypes as a means of making adolescent male readers’ lives better. Instead, the reviewer finds that there is good information in Brozo’s book, but it is not the ultimate solution for solving all of the issues facing boys’ literacy today. Information and Reviews International Reading Association http://www.reading.org/publications/bbv/books/bk175/ This review by the publisher notes the book’s incorporation of classroom examples that demonstrate how different activities can be used in conjunction with reading of texts that follow the ten archetypes presented in the book. The review also hints at the book’s community literacy efforts in that it mentions community involvement in order to positively influence boys’ literacy. This review is quite helpful in that it links to the Table of Contents and even offers a sample chapter download to preview text from the book itself. Information and Reviews George Mason University, Research Channel http://www.researchchannel.org/prog/displayevent.aspx?rID=5217&fID=568# This review puts the book To Be a Boy, To Be a Reader in the context of the broader literacy situation and the disparity between girls’ literacy and boys’ literacy. The site presents an interview with Dr. Brozo, with him explaining his background and how he came to be interested in the area of boys and literacy. Throughout the interview, Dr. Brozo discusses the declines that begin to occur in boys’ literacy; he then advocates for more attention to be dedicated to this issue so that the statistics and current trends can be reversed. Whether it be through archetypal studies (as he suggests) or other active instructional practices, this interview and review highlights Dr. Brozo’s recognition of an important issue facing educators and society today. Information and Reviews The Galt Global Review http://www.galtglobalreview.com/reviews/reviews_booknotes14.html This review highlights the uniqueness of Brozo’s book, focusing on the use of strategies with the ten positive archetypes as a means of reaching struggling and reluctant male readers. The review considers the book to be “one-of-a-kind” as it presents classroom ideas and community-building ideas to counter the problems with boys’ literacy in today’s schools. This review is joined with three other reviews of books that focus on the issue of boys and literacy, thus indicating the relevance of Brozo’s book at this given time. Summary of Book Introduction William G. Brozo is a professor at George Mason University, where he focuses on Language and Literacy. He was a high school English teacher, where he saw firsthand the struggles that many adolescent males face as readers. Reaching out to these students sparked further interest in him, as he set out to observe and collect data on readers, specifically struggling male readers. With his experience as an educator and a researcher, Brozo is quite qualified to present ideas and strategies for reaching and connecting with adolescent male readers. He ties his strategies and ideas to statistics, highlighting the struggles that male students are facing around the country and even around the world. With the recent publication of several books that focus on the needs of boys as they hit adolescence (in the year 2000), Brozo’s work fits in well with the education and societal trend of seeking resources and strategies for accommodating the unique needs of this part of society. Summary of Book Introduction, continued The specific topic of this book is addressing the needs of teen and preteen boy readers by introducing them to positive male archetypes through which they can identify and get hooked on reading. The overall purpose of the book seems to be to provide background and justification for the ten positive male archetypes in the context of both fiction and nonfiction literature that will appeal to teens and preteens. Having taught high school and having seen the statistics regarding boys and violence, Brozo recognized the need for positive changes to occur in the realm of literacy and adolescent boys. Thus, his point of view and frame of reference centers on his belief that boys can become active readers and successfully literate if teachers and adults of all professions encourage boys to seek out books on topics that interest them. In essence, Brozo believes that literature and reading can be methods through which adolescent boys can seek positive paths in life, away from the negative images that are often stereotypically attached to their gender. Summary of Book Introduction, continued This book is written for teachers, as it provides numerous ideas and detailed strategies that can be implemented in the classroom. Additionally, the book includes extensive reading lists by archetype and category, thus allowing teachers to more easily incorporate selected texts into their classrooms. Other professionals in education, as well as concerned adults in the community may find this book useful, as it encourages adults to become involved in the literacy lives of adolescent boys. Brozo recognizes the need for good, positive role models, and thus, this book would be beneficial for any adults who work with reluctant readers, specifically males. Summary of Book Focus of the Book Brozo does advance an explicit thesis in his book, as he notes “the premise underpinning this book is that engaging adolescent boys in literacy should be the highest priority when developing reading curricula and seeking to foster independent reading habits” (Brozo, 2002, p. 2). His thesis is supplemented with his focus on the use of archetypes as a means of engaging male readers with literature that reflects parts of their own lives. Brozo’s purpose for writing the book centers on his belief that archetypes will serve as a motivation for male readers to increase their literacy by losing themselves in books that are relevant for their own lives and the struggles and obstacles that they face as men. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued There are several critical pieces of evidence to support Brozo’s focus on archetypes as a means for engaging adolescent males with reading. First, literature of all genres and from all time periods reflect archetypes as a means of understanding more deeply the plight of the characters. Second, adolescent boys often struggle with finding their place in a world full of violence, drugs, etc. The use of archetypes can help male students understand the roles that will allow them to be successful on their journey into manhood. Third, the stereotypical images portrayed in popular culture can affects adolescents’ sense of direction and purpose. Thus, the use of archetypes can help male students see themselves as purposeful individuals through the lens and context of literature. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued Adolescent readers, specifically boys, struggle in large numbers in my profession and specifically in English Language Arts. Their reluctance to read and engage with texts spills over to other content areas, as well. Thus, Brozo’s book fits well within the growing body of knowledge in this area. His book, published in 2002, aligns well with the works of Smith and Wilhelm (Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys and Going with the flow: How to engage boys [and girls] in their literacy learning), Booth (Even Hockey Players Read), and Knowles (Boys and Literacy: Practical Strategies for Librarians, Teachers, and Parents). Brozo’s work is unique, however, in that his approach to addressing the needs of adolescent boy readers is quite specific, focusing on the archetypal approach. Other texts centered on boys’ literacy are much less specific and rely on generalized ideas and approaches to engaging students with texts. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued This book presents Brozo’s personal observations in classrooms, detailed classroom vignettes, personal narratives and commentary from students, and literary analysis of the archetypes set forth by Carl Jung. Brozo’s incorporation of Jung’s work regarding archetypes establishes his sincere belief that this approach will benefit struggling and reluctant male readers. He notes that he “present[s] the 10 positive male archetypes to help teachers guide adolescent boys through the archetypal world of the male psyche” (Brozo, 2002, p. 26). He maintains a balance between incorporation of archetypes and literature with the underlying goal of making this a reasonable idea for teachers and educators to actually implement in the classroom. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued Brozo’s consideration and recognition of classroom structure is evident as he continues arguing his thesis supporting the use of archetypes. For example, he includes ample discussion of how the archetypes manifest themselves in young adult literature, thus refocusing his emphasis on how this approach can realistically be implemented in a secondary classroom. Furthermore, he focuses on each of the ten archetypes individually, providing strategies and ideas for teaching with the archetypes. From anticipation guides to concept maps, Brozo puts forth numerous ideas that balance effective classroom practices with the incorporation of archetypal literature. There are alternate ways of suggesting ideas to engage adolescent male readers. Many authors (McFann, O’Donnell, Rief) recommend providing male readers with books on topics that are interesting to them. This, of course, is a way to encourage more adolescent males to read. In fact, Brozo recognizes the importance of incorporating student interest in classroom reading. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued However, Brozo feels that simply giving students interesting books to read will do little to change how adolescent boys actually interact with texts. Thus, Brozo maintains that students’ interests can be considered when seeking books that align with the positive male archetypes. Brozo’s book does raise the issue of gender and literature, as his focus is on male literacy. Some educators will likely question the merit of focusing solely on boys, rather than seeking ways to increase literacy among both boys and girls. However, as the literacy rates for girls are still higher than that of boys, perhaps that is an issue that has been set aside for now. No matter the specific focus of Brozo’s book, he is quick to acknowledge that many of the strategies presented are useful for all students regardless of their gender. Additionally, he suggests that even girls might benefit from the study of male archetypes, as it would allow them to gain a different perspective on masculinity than that which is presented in popular culture and the media. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued Brozo’s ideas do relate to educational theories, as he seems to support students’ self-constructed knowledge in connection with literature and students’ own experiences. Vygotsky’s idea of the zone of proximal development suggests that students can learn from their current experiences in preparation for the next step of maturity; this aligns with the different archetypes in that men will spend time fulfilling different archetypal roles, moving on to others at different phases of their lives. In addition, Brozo’s use of different strategies, as well as different types of texts coincides with Gardner’s belief in multiple intelligences and multiple ways of learning. With each reader bringing his own experiences to the texts and to the archetypal journey, each learner processes the information at their own pace and in their own unique way. Summary of Book Focus of the Book, continued Furthermore, Brozo’s use of archetypal characters in literature as examples and models for male readers aligns well with Bandura’s Social Learning Theory and the belief that people in general learn from observing and interacting with others. This book offers much advice and support to educators as it provides extensive reading lists, classroom strategies with samples, a teaching unit focusing on masculinity as explored through young adult literature, and community-based ideas for getting adults outside of the classroom involved with students’ literacy. Brozo’s book offers comprehensive ideas with specificity, thus allowing teachers to implement them in their own classrooms with relative ease. Personal Response I was quite intrigued by this book, as I was previously unfamiliar with the male archetypes and the ways in which they manifest themselves in literature. I was initially overwhelmed by the content and the subject matter; however, as I read more of the book, I recognized Brozo’s down-to-Earth language and the ease with which he presents the ideas and strategies for using the information with students in the classroom. The evidence Brozo presents is quite convincing, as he cites many statistics related to boys’ literacy and the societal implications of males who are illiterate. In looking at websites, scholarly articles, and other texts, Brozo does seem to be quite recognized for his work. Scieszka, another author who focuses on literacy for male readers, wrote the foreword for Brozo’s book, indicating that there is a respect in the field for Brozo and the attention he has garnered with regards to this important topic. Personal Response, continued As noted before, Brozo’s work does fill a more specific niche in the broader area of boys’ literacy. Other more general texts on the topic of literacy and males include Smith and Wilhelm’s Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys and Going with the flow: How to engage boys [and girls] in their literacy learning), Bloom’s Even Hockey Players Read, and Knowles’s Boys and Literacy: Practical Strategies for Librarians, Teachers, and Parents. Brozo’s conclusion and argument does not conflict with any other books or courses I’ve read or dealt with, as his argument was largely focused on the use of archetypes as a means of furthering boys’ literacy in a positive way. I find nothing wrong with suggesting positive and more personalized approaches to engaging students with literature, as I feel that is a way to get more students involved with their own lives and their own schooling. Prior to this book, my ideas related to boys and literacy had primarily focused on the notion that boys like nonfiction and sports books. This idea has been reinforced, but is now largely supplemented by recognition of the large collection of fiction and young adult books that can be used to help male readers connect with and understand male archetypes. Personal Response, continued I would definitely recommend this book to other educators, especially high school English teachers, as the use of male archetypes seems to be an innovative way to focus students’ attention on literature as a reflection of life. Furthermore, I believe that the wealth of strategies and booklists included in this text will benefit teachers in their efforts to expand their classroom libraries and to expand their own knowledge of relevant and engaging young adult texts. Brozo does a good job incorporating student feedback, specific classroom strategies, and detailed descriptions of the ten positive male archetypes. All of these things make this book a winner in my eyes, as I feel that I can now more effectively reach out to and work with my adolescent male readers. Instructional Tip #1 Brozo (2002) notes that “biographies help adolescents discover goodness in real-life men and introduce them to archetypes on which to base their own lives” (p. 18). In the classroom, this can be implemented by doing a genre focus on biographies. Each six weeks, students will select from biographies on men from history and current events, leading them to explore the ways in which real men’s lives play out and reflect the decisions that they make in life. Students can then create Venn diagrams to compare and contrast the archetypes portrayed in the biographies of these real-life men. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.6A, in that students’ vocabulary will be increased through the exploration of the biography genre and the introduction to archetypes and associated content. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 010 in that the selection of biographies and discussion of archetypes will pave the way for adolescent boys’ literacy to develop further. Instructional Tip #2 Brozo (2002) suggests that “books that are steeped in positive male archetypes may actually dispel stereotypical notions of what it means to be masculine” (p. 19). In the classroom, students can read self-selected books that have strong male characters, such as Gary Soto’s Taking Sides or Walter Dean Myers’s Hoops. Students will create a character sketch of one of the stronger male characters in the book. Then, students will choose a male character from a television show, creating a character sketch of that person. In the end, students will compare and contrast the portrayal of the male character in the book with that of the male character in real life. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7E, in that students will be analyzing texts and comparing and contrasting the characters within them. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 006 in that the joining of a literature text with popular culture reflects the importance of engaging students with their own lives in order to facilitate comprehension. Instructional Tip #3 Brozo (2002) presents data that highlights a “grim picture of young men engaging in increasing levels of drug addiction, violence, homicide, and suicide” (p. 21). In the classroom, students need opportunities to see men portrayed in a more positive light. Students will select articles from the newspaper that portray men in a negative light. Then, students will select articles from the newspaper that portray men more positively. Students will choose one negative article and one positive article and will write a plan for how the man portrayed positively could influence for the better the man portrayed negatively. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7H, in that students will be working with two different articles and will be drawing inferences to support their plan of action. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 008 in that writing is used as a means to further students’ understanding of the texts. Instructional Tip #4 Building on Carl Jung’s ideas, Brozo (2002) notes that “positive male archetypes are an adolescent boy’s guides along the often dark and jagged way of this interior journey” (p. 25). In the classroom, students will look for real-world examples of the positive male archetypes by reading different magazines and newspapers. In pairs, students will look for multiple examples of the archetype which they have been assigned. Students will then join with another pair to teach them about the archetype with which they have been working. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.13E in that students will be gathering information about their archetype by reading different articles. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 006 in that multiple texts are used to allow students to build their comprehension on a single topic and archetype. Instructional Tip #5 Brozo (2002) notes the importance of the Pilgrim archetype by reiterating that “young boys need and crave, especially in their souls, meaningful and vibrant interaction with others who can keep them in touch with the wanderer within” (p. 27). In the classroom, students will read The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child by Francisco Jimenez. Students will keep a dialectical journal in which they pull quotes from the book that connect with the Pilgrim archetype. Students will select their most important quotes at the end of the book, sharing them with the class. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.10B in that students are pulling quotes from the text in order to supplement and support their own responses and connections to the Pilgrim archetype. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 006 in that students are engaged in deeper comprehension of the text through use of a dialectical journal as they read. Instructional Tip #6 Brozo (2002) observes that “modern cultures eschew initiation rites of adult males, leaving boys with fewer reference points for responsible masculine behavior” (p. 29). In the classroom, students will collect popular culture examples of how modern society defines manhood. Students will compare those examples with the ways in which popular culture portrays boys and teens. Students will create a Venn diagram comparing these portrayals, highlighting their understanding of how popular culture accurately or inaccurately portrays masculinity. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.11 in that students are looking at similar ideas through different texts. Furthermore, it supports TExES PPR Competency 008 in that students are engaged in active learning connected to their own lives and popular culture. Instructional Tip #7 In planning a unit to engage students, Brozo and his colleagues recognized the importance of using “literature as a catalyst for critical explorations of masculinity” (Brozo, 2002, p. 104). In the classroom, students will work in literature circles to read Bucking the Sarge, Tangerine, Whirligig, and Canyons. Working with their literature circles, students will create a concept map to define the word ‘masculinity’ based upon the characters in the novel. After reading the novels, the class will create a larger concept map detailing all of the meanings and nuances of masculinity that were explored in all of the novels. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.11 in that students are exploring elements of masculinity in the context of different texts. Furthermore, it supports TExES ESL Competency 005 in that students are engaged in expanding their vocabulary and word knowledge through reading and writing. Instructional Tip #8 Brozo (2002) notes the importance of engaging male readers in the United States and around the world when he reiterates that “placing suitable books in teen and preteen boys’ hands is also one of the goals of education in the United Kingdom” (p. 93). In the classroom, provide students with access to a wide range of books and reading materials, including newspapers, comics, how-to books, and magazines. Additionally, students will take class trips to the library at least once a month, allowing the librarians to discuss with male students the availability of books that might engage them. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.8 in that students have access to a variety of texts and print resources. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 010 in that the teacher provides ample instructional resources and texts to match the needs of the students. Instructional Tip #9 Brozo (2002) stresses that “a book talk that includes an enthusiastic delivery, expressive reading of excerpts, and a cliff-hanging conclusion is especially useful for engaging reluctant readers” (p. 89). In the classroom, bring in two or three of your favorite books with male protagonists. Choose an action-filled part of the book and read it aloud for the students, demonstrating the excitement that can be created through reading. Then, have students work in pairs to dramatize favorite parts of a book they have read and allow them to present it to the class as a form of booktalking. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.15 in that students are engaged with different texts through listening and performing. Furthermore, it supports TExES ESL Competency 004 in that students have the opportunity to hear language modeled for them, along with having the chance to practice creating their own language-rich presentation that is linked to a text. Instructional Tip #10 Brozo (2002) stresses the importance of meshing classroom activities with students’ lives by stating that “teachers…should first discover what adolescent boys’ interests are outside of school in order to ultimately introduce them – particularly struggling and reluctant readers – to enticing literature” (p. 78). In the classroom, students will create a collage that represents their hobbies and interests outside of school. Then, students will do a gallery walk around the room, putting post-it notes on the collages to indicate books they have read that they think their classmates might like based on the interests displayed in the collage. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7B in that students are considering their own interests and lives in order to connect with reading. Furthermore, it supports TExES ESL Competency 005 in that there are opportunities to connect reading and content knowledge to students’ own lives and interests. Instructional Tip #11 Brozo (2002) notes that “most teen and preteen boys rarely see fathers or any adult men reading anything” (p. 97). In the classroom, guest readers will visit every Friday to take part in a reading time. Assistant principals, male teachers, community leaders, and parents are invited to come in on Fridays to read with and/or for the students. Students will write letters to the guests, sharing their thoughts and feedback with them regarding their visit to the class. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7A in that students will see adults who enjoy reading for pleasure, thus encouraging students to seek out similar opportunities for themselves. Furthermore, it supports TExES ESL Competency 009 in that role models from all walks of life are welcomed into the classroom to facilitate appreciation and acceptance of literacy goals and reading among students. Instructional Tip #12 Brozo includes striking statistics indicating that “in large urban areas, as many as 40% of African American boys do not graduate from high school, whereas 40% of African American men have problems with literacy” (Brozo, 2002, p. 97). In the classroom, students will select a role model in society (past or present) who is African American. Students will read at least two texts about this person (including newspapers, biographies, magazine articles), creating an outline of their life. Then, students will create a collage that represents this person’s life and the archetype that they feel was best represented in the two texts they read. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7D in that students will compile the information they glean from the texts into different organizational forms. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 2 in that a variety of resources and activities are being used to further students’ literacy. Instructional Tip #13 Brozo (2002) suggests that “exploring media portrayals of boys and men would appear to be an effective approach to take to help young men think critically about how gender stereotypes are promulgated by commercial advertisers” (p. 125). In the classroom, students will work in groups to analyze portrayals of men in three different contexts – movies, magazines, and television. Each group will select three texts to read/watch, taking notes on how men are seen in these contexts. Then, each group will present a presentation to the class outlining the results of their study, as well as possible solutions for remedying such stereotypes. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.12 in that students will analyze different texts to draw a conclusion about stereotypes and gender. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 2 in that a variety of reading and writing activities are used to allow students to delve deeper into the content and the ways in which popular culture affects how different genders are portrayed. Instructional Tip #14 Based on his own experiences, Brozo (2002) concludes that “every concerned adult can inspire teen and preteen boys to read” (p. 136). In the classroom, students will select a member of the campus staff to work with as a buddy reader every Wednesday during Advisory time. Students can work with any adult – a counselor, the librarian, another teacher, secretaries, the building manager, etc. Students will to their buddy reader a book in which they are interested. Then, every Wednesday, the student and the buddy reader will keep a reading log, keeping track of how far they have read, as well as a narrative about the discussions they had regarding the book. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7A in that students will have the opportunity to work with other readers , namely adults, to gain a deeper sense of enjoyment from reading. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 2 in that the teacher is providing multiple grouping arrangements for students so that their learning is reinforced and scaffolded in different contexts. Instructional Tip #15 Brozo (2002) discusses and recognizes that “boys often need help discovering their interests; yet, in households where parents are extremely busy, boys are usually left to their own devices to discover what turns them on” (p. 140). In the classroom, students will read a series of Gary Soto short stories and/or novels, highlighting teenage boys and their hobbies. Students will create a T-chart in which they list their hobbies and pastimes on one side, and the hobbies and pastimes of the characters on the other. Students will then write a reflective paragraph noting how they plan to implement a hobby similar to a character from one of the stories or novels. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7 in that students will consider their own interests and lives as part of the context for their reading. Furthermore, it supports TExES ESL Competency 005 in that the activities presented build upon the connections between reading and writing as a means for gaining deeper insight into a text and its relevance for students’ lives. Instructional Tip #16 Brozo (2002) cites research that notes that “in addition to increasing languaging about texts, quality mealtime conversation between parents and children has been shown to reinforce family unity” (p. 152). In the classroom, students select two passages from a book they are reading. They select one passage they think a parent would like and one passage they think a sibling or other relative would like. During the next two weeks, students find time to read these passages aloud to their family. Then, the students tell their family why they like the book. Students bring back to school a reflection on how their family reacted to the passages, as well as how they felt about sharing a book with someone else. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.14 in that conversation and listening and speaking skills are incorporated to supplement students’ literacy development and reading of texts. Furthermore, it supports NCATE/TESOL Program Standard 2 in that the teacher is including and building learning opportunities that incorporate authentic conversation for students. Instructional Tip #17 Brozo (2002) comments about his observations in a classroom, noting that the teacher’s “male students were rarely self-selecting books because of fear of ridicule…If a boy chose something that other boys deemed a ‘girl’s book,’ the book would likely be returned to the shelf, becoming a ‘pariah’ among the males” (p. 91). In the classroom, a wide range of materials should be provided, especially those that appeal to male students. For example, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated, BET, and Boy’s Life are magazines that can be included in the classroom. Also, books by popular male authors such as Avi, Stephen King, Gary Soto, and Gary Paulsen can be a good place for male readers to begin their journey through selecting books. Allow students to make suggestions and additions at least once a week. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7 in that students have opportunities to self-select books that interest them and can explore the types of books that they feel are reflective of their own lives. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 4 in that the classroom is a literacy-rich environment, full of different types of texts that will appeal to a wide range of student interests. Instructional Tip #18 Brozo (2002) notes that “the Wildman [archetype] emboldens young men to challenge the status quo, and question their own and others’ complacency, conformity, and popular ideology…[which] helps adolescent boys see through fads and strive for solid and permanent values instead” (p. 37). In the classroom, students will read Jerry Spinelli’s Crash. As they read, students will create a character journal from the point of view of the main character Crash. Students will make note of the ways in which Crash acts in order to be a part of the “in crowd.” At the end of their journaling, students will write a letter to Crash, detailing how they feel he did or did not fulfill the Wildman archetype. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7 in that students will use the character journal as a means of monitoring their own comprehension of the text. Furthermore, it supports TExMaT Master Reading Teacher Competency 006 in that the activities encourage comprehension and metacognition as students read. Instructional Tip #19 Brozo (2002) points out that “teen and preteen boys need models of the Healer archetype who fit into their complex and high-tech worlds … [and] teachers should work to guide boys through the inward journey of self-healing while encouraging boys’ outward acts of public service for those who are hurting” (p. 39). In the classroom, students will work in groups to create a school-wide service project to address a need on campus. Students will conduct interviews of adults and other students on campus and will present the findings to their group members. Then, students will draft a plan of action to rectify the need on campus. After the project, students will write a reflective letter to themselves, detailing how well they felt they modeled the Healer archetype. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.16 in that students communicate their ideas to others in a coherent manner. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 001 in that the project provides opportunities for students to strengthen their oral communication skills in a productive manner that aligns with their study of archetypes. Instructional Tip #20 Brozo (2002) found that “providing boys with models of real-life men who love the truth, as well as examples of male literary characters who embody Prophetlike qualities, can help boys more readily access this powerful archetype for lifelong inspiration” (p. 41). In the classroom, students will brainstorm definitions for the word ‘prophet,’ leading to a broader picture of what the Prophet archetype represents. Then, students will read Malcolm X: By Any Means Necessary in conjunction with excerpts from The Autobiography of Malcolm X. As students read, they will annotate the text, highlighting characteristics of the Prophet archetype in yellow and non-Prophet archetype characteristics in blue. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7I in that students will read and use annotation strategies to better comprehend the text. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 010 in that the teacher is providing instructional activities specific to the texts in order to facilitate student understanding. Instructional Tip #21 Brozo (2002) recognizes that “to access the Magician archetype, boys need to become acquainted with their intuitive selves…[and] teachers may help boys become comfortable with this archetype by finding both ancient and contemporary examples of males who have used their intuitive powers to improve their lives and the lives of those around them” (p. 35). In the classroom, students will read Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, keeping a reading log of all of the examples of when Prospero demonstrates characteristics of the Magician archetype. Then, students will compile a class list of characteristics of the Magician archetype, aligning their list with observations from their own lives and the real world. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.8 in that students read classic literature, but also consider it from a more modern perspective. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 2 in that students’ real world observations become a part of their exploration of the content and the literature they read, thus expanding their literacy base. Instructional Tip #22 Brozo (2002) suggests that boys should be introduced to “books with characters who possess different archetypal qualities” (p. 6), namely the ten positive male archetypes: Pilgrim, Patriarch, King, Warrior, Magician, Wildman, Healer, Prophet, Trickster, Lover (Brozo, 2002, p. 26). In the classroom, students will create posters to represent each of the ten male archetypes. Each poster will contain popular culture images, as well as quotes from literature texts to best represent the characteristics emulated through each archetype. Students will then complete a gallery walk around the room, leaving post-it notes on the archetypes with which they feel that they have identified with at some point in their life. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.9 in that students will define specific archetypes based upon their own lives, the literature they have read, and popular culture. Furthermore, it supports TExES PPR 8-12 Competency 008 in that the teacher is facilitating active learning for students through a variety of interrelated activities. Instructional Tip #23 Smith and Wilhelm (2006) suggest that “making what we teach matter through inquiry addresses the boys’ desire for a focus on the immediate experience” (p. 56). In the classroom, students will brainstorm activities and hobbies that they believe interest male students. Then, students will create a list of questions related to this brainstormed list. Students will take their list of questions to the library, where they will seek out nonfiction and fiction books that will address some of their questions. Students will use these books as their self-selected reading for the next six weeks. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.8 in that students read for purposes related to their own interests and inquiry. Furthermore, it supports TExES PPR 8-12 Competency 008 in that the teacher is building the classroom activities around the interests of the students, thus making it a more personalized learning journey for the students. Instructional Tip #24 Blair and Sanford (2004) discuss that “societal expectations of boys direct them to be responsive in particular ways, such as being loud, witty/mocking, individualistic, and self-fulfilling” (p. 453). In the classroom, students will create a list of adjectives that they feel are associated with boys – both stereotypically and non-stereotypically. Then, students will seek out magazine and newspaper articles that either support or contrast with the adjectives on the list. Students then create a list of adjectives that they hope society will use to describe them and their lives. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.12 in that students read texts in order to analyze the portrayal of boys in them. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 2 in that the learning is scaffolded from students’ personal experiences to those established in texts. Instructional Tip #25 Young (2000) notes that during her work with boy readers, “the boys produced a new meaning for men being brave as they interacted with their texts and one another” (p. 330). In the classroom, one group of students will create a definition of a brave based upon their reading of Superman and Batman comics. Another group of students will create a definition of brave based upon Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet. Students in each group will present their definitions and supporting textual evidence to the class; at the end, the other group can challenge or question the group’s definition. At the end of the class, a definition of brave will be created, taking into consideration the revelations found in both sets of texts. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.12 in that students will compare and contrast an aspect of masculinity based on several texts. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 4 in that there are multiple texts and interactions with text during the lesson. Instructional Tip #26 McFann (2004) reiterates that “families play a critical role in promoting male literacy, and the impact is especially powerful if the father is involved to help boys see reading as something that males do” (p. 21). In the classroom, students will create children’s books based upon fairy tales with strong male characters. The students will then present the children’s books to elementary students in the district, establishing a reading partnership with these students. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.22 in that students are creating their own products to represent their understanding of texts. Furthermore, it supports IRA Standard 4 in that the teacher is facilitating modeling of reading and writing behaviors for students, so that they, too, can pass along these habits with the elementary students with whom they present their story. Instructional Tip #27 O’Donnell (2005) notes that “recognizing the new face of literacy and providing boys with springboard materials is a key to fostering book-reading boys” (p. 19). In the classroom, students will look at Troy Aikman: Super Quarterback in conjunction with a documentary about Troy Aikman’s life. Students will make a Venn diagram comparing the type of information that was learned from the two different types of texts. Then, students will peruse annotated book lists detailing books about sports. Students will select a book to read based upon their interest and reactions to the texts they worked with in class. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.8 in that students will read and learn through a variety of text types. Furthermore, it supports TExES PPR 8-12 Competency 004 in that the teacher is providing different activities through which students can co-construct their knowledge and further their learning. Instructional Tip #28 Smith and Wilhelm (2002) suggest that “society, which defines and enforces social definitions of manhood, must actively interrogate and redefine masculinity” (p. 6). In the classroom, students must explore different definitions of masculinity and manhood as it relates to their own lives and the lives of others. Students will read fairy tales from around the world, annotating the stories for examples of masculinity. Then, students will create a chart reflecting the different ways manhood was portrayed in different fairy tales, grouping them by region of the world. Finally, students will use these examples to begin thinking of their own definitions of becoming a man. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.7 in that students will be creating a definition based upon their understanding of the texts being read. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 006 in that multiple texts are being used to further students’ comprehension. Instructional Tip #29 Rief (2000) notes that students “become passionate writers when they are reading books that matter to them as human beings” (p 57). By incorporating books that appeal to male readers and that provide positive directions through the positive male archetypes, students will be well on their way to developing deeper literacy skills. In the classroom, students will choose a book that has been the most important book to them so far during the school year. Students will choose their favorite passage from the book and will imitate the author’s style and write a passage based on their own life, reflecting the same archetype that was explored in the book. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.2 in that students will respond to their reading by becoming writers and imitating an author’s style. Furthermore, it supports TExES Reading Specialist Competency 008 in that the teacher facilitates students’ growth as writers by strengthening their skills as readers, too. Instructional Tip #30 Young and Brozo (2001) explore the topic of boys’ literacy further with Young noting that “boys who wish to be viewed as boys of a certain sort (e.g. jocks, nerds, skaters, gays) will read, write, and think like others who claim membership in that particular Discourse of masculinity” (p. 320). In the classroom, male students need to see male characters in a variety of forms and texts. First, the class should brainstorm a list of characteristics relevant to all of the male characters they can think of from literature. Then, students should make a separate list of characteristics that they feel are missing from the first list. Finally, students should discuss why it is important to broaden the types of texts they read both in class and out. This activity supports the English I TEKS, specifically §110.42.2 in that students are exploring a topic by using brainstorming and prewriting activities. Furthermore, it supports TExES PPR 8-12 Competency 008 in that the teacher is facilitating active learning for students by building on their prior knowledge and connections. Teacher Interview: Ideas from this Book I spoke with Mrs. D., a 10th grade English teacher. Mrs. D was familiar with archetypes, but had never before considered using them as a framework for increasing students’ literacy. Instead, she has traditionally taught archetypes to her Pre-AP students as a means for analyzing texts. She was intrigued by the comprehensive book lists included at the end of the book, as well as the method through which the author builds on the positive male role models. Mrs. D said she would be interested in looking at a few of the male role models through the suggested texts, but indicated that she would not follow all of them, simply because she would want to balance it with appropriate materials for female students, too. Teacher Interview: Professional Development Mrs. D does have some opportunities for professional development, especially if they relate to the TAKS test or a specific initiative on their campus. For example, right now they are receiving professional development on open-ended responses, as that is an area that was weak on their students’ benchmark tests. Additionally, during staff development days, Mrs. D said that they do have the opportunity to work in small groups and to build on their own department’s professional knowledge. She said that she likes that type of professional development the most because it is highly relevant to their campus needs at that time. Teacher Interview: Professional Organizations Mrs. D does not belong to any professional organizations at this time. When I asked her about organizations with which she was familiar, she only named the National Council of Teachers of English. I told her about the International Reading Association, as well as state-based literacy/English Language Arts organizations, but she was not familiar with them. Mrs. D pointed out that once you’re in the classroom, many things fall by the wayside, including participation in the professional organizations. She commented that she wished her department would encourage such participation so that more people could bring forth ideas from these organizations. Teacher Interview: Professional Conferences Mrs. D has attended one professional conference in San Antonio – the New Jersey Writing Project in Texas. She said she enjoyed being able to dialogue with her colleagues away from the school campus, as that seemed to build their camaraderie more than if they had been attending a workshop on campus. Mrs. D added that she really liked how the conference provided different sessions for different grade levels, as she was able to go to a middle school workshop to get a feel for ideas that might be useful for the teachers in her vertical team. Overall, she liked being able to learn something new in a different environment. Webliography http://www.education-world.com/a_issues/chat/chat045.shtml This website presents an interview with Jon Scieszka as he discusses his initiative to draw attention to boys’ literacy through his website “Guys Read.” In the interview, Scieszka points out startling facts related to boys’ literacy, but also gives suggestions for overcoming some of these statistics. For example, he discusses the importance of having male role models in schools, so that boys can see that success is possible. The interview concludes with Scieszka’s suggestions of books for male readers, many of which could easily be added to classroom libraries. Webliography http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ALAN/winter99/gill.html This website presents an article in the online journal ALAN Review entitled “Young Adult Literature for Young Adult Males.” In the article, author Sam D. Gill indicates the importance of finding books that will actually appeal to male readers, especially those who are already reluctant readers. The end of the article includes a listing of books for male readers, grouped by types of stories (i.e. nature/adventure, identity, historical, sports). This listing could be given to students in class, so that they can self-select books that might interest them. Webliography http://www.teacherlibrarian.com/tlmag/v_30/v_30_3_feature.html This website features a February 2003 article in Teacher Librarian Magazine entitled “Overcoming the Obstacle Course: Teenage Boys and Reading.” The article highlights recent research regarding boys and literacy, much of which was included in the book Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys. Additionally, the article includes results from a survey administered to teen readers, indicating reasons why teen boys don’t seem to enjoy reading; over 39% of them felt is was boring and not fun. To help counteract that, the article suggests incorporating more magazines and newspapers before delving into longer works such as novels. The end of the article includes a suggested reading list for 7th grade boys, as well as nonfiction categories that seem to interest boys the most. These categories could be a starting point for teachers wanting to increase their reading of nonfiction in the classroom. Webliography http://content.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=1543 This Scholastic article entitled “If Your Boy Won’t Read” presents several ideas for enticing male students with reading, even at home. Some of the big ideas presented on this site include modeling good reading habits, reading about your son’s interests and hobbies, and starting off with comics and/or graphic novels. These ideas can be easily adapted in the classroom, too, as teachers can incorporate more visual texts with the content area, which will increase students’ literacy in many ways. Also, teachers can build a classroom library that includes many books that focus on students’ interests without distracting from the books that are mandated by the curriculum. Webliography http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/brochure/meread/meread.pdf This site presents a pdf file entitled “Me Read? No Way! A Practical Guide to Improving Boys’ Literacy Skills.” The document was produced for the Ontario Ministry of Education and presents numerous teaching strategies to help boys engage with texts more consistently and more actively. For example, the document suggests that teachers build on social interaction during the reading process by allowing male readers to read in groups or to dramatize passages from a book. All of the strategies presented in the document are worthwhile, as the aim of the site is to increase student literacy through engaging activities in the classroom. Webliography http://education.qld.gov.au/students/advocacy/equity/gendersch/issues/lifting.html This site from Australia presents several pages of information related to boys and literacy. There is discussion of how gender frameworks apply to boys’ literacy, what counts as literacy in the school setting, a look at masculinity versus literacy, and links to real male students’ opinions about literacy and English. This information is useful for the classroom, as it gives us a direction in which to move in order to increase male students’ literacy. By understanding how some students feel in class and by considering the perceptions that are associated with being male and being literate, teachers can then work to develop strategies and instructional practices to counteract some of these things. Webliography http://guysread.com/ This website focuses solely on books that guys might enjoy reading. Set up similar to a database, visitors to the site can search for books by looking at already established lists or by using the search feature. You can search by author, topic, or favorite book, thus allowing more possible books to be retrieved during the search. This site would be very useful in the classroom, as it would help more reluctant readers choose a book based upon other guys’ recommendations or books that they have already read. Webliography http://www.penguin.com.au/PUFFIN/TEACHERS/Articles/understand_ male.htm This website presents an article entitled “Understanding the Reluctant Male Reader.” The article considers different factors that contribute to reluctant readers, and categorizes such readers as “dormant,” “uncommitted,” and “unmotivated.” In exploring these factors and their relation to male readers, the author contends that teachers and librarians should consider male readers’ interests when seeking books for them. Additionally, the author reminds us of the importance of not devaluing series books or comics simply because they are things that we may not like to read. In the classroom, these ideas can be put into place by having students complete an interest survey or something similar so that there is a clearer idea of what types of books will engage them as readers. Bibliography Blair, H.A., & Sanford, K. (2004). Morphing Literacy: Boys Reshaping Their School-Based Literacy Practices. Language Arts, 81, 452-460. This article discusses the different literacies that students, specifically boys, face in their lives, and considers the role that school-defined literacy plays in boys’ lives. The authors note that teachers and schools sometimes dismiss boys’ interests, when in reality, the boys are continuing to develop literacy skills in relation to things that are actually of interest to them. By embracing boys’ interests, teachers and schools can help strengthen these literacies. Bibliography McFann, J. (2004). Boys and books. Reading Today, 22 (1), 20. This article presents a mix of research findings related to boys and literacy, as well as recommendations for helping male students find books that they will enjoy reading. The article shares several statistics comparing girls’ literacy to that of boys, but suggests that presenting reading material in a new way and making connections with positive male role models will help increase boys’ success with literacy. Bibliography O’Donnell, L. (2005). Are Canadian boys redefining literacy? Reading Today, 22(4), 19. This article discusses how boys in Canada seem to be falling behind in literacy when compared with their girl counterparts. The article considers different reasons for this disparity, largely focusing on boys’ perceptions of reading more of a female-oriented activity. In the end, the article discusses was to invite boys into reading by making it more connected to things that they already enjoy, such as video games, websites, and other technology-based activities. Bibliography Rief, L. (2000). The Power of Reading: Practices that Work. Voices from the Middle, 8, 49-59. This article presents snapshots of different students of different ages and their approaches to reading. As she discusses the students’ behaviors, Rief incorporates strategies that she uses with each of the students to encourage them to continue reading. From read alouds to poetry as a form of reading response, Rief presents ideas for engaging students with the reading process, thereby helping them realize that it is not an inactive, isolated process. Bibliography Smith, M., & Wilhelm, J. (2006). Going with the flow: How to engage boys [and girls] in their literacy learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. This book focuses on the conditions in which boys find themselves in terms of their home literacies versus their school literacies. In looking at ways to engage students with reading more regularly, the authors focus on instructional practices to help students become more active readers. One such approach involves designing lessons using inquiry, so that students’ own interests and questions drive the lessons and ultimately, the reading of texts. Bibliography Smith, M., & Wilhelm, J. (2002). Reading don’t fix no Chevys: Literacy in the lives of young men. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. This book presents ideas for making reading and literacy more relevant for students, especially adolescent males. The authors include numerous interviews with students, thereby adding to the authenticity of their premise that many males see little usefulness in reading books in school. The book includes reasons for apathy towards reading among high school males, but also provides suggestions for overcoming this apathy with students. Bibliography Young, J.P. (2000). Boy talk: Critical literacy and masculinities. Reading Research Quarterly, 35, 312-337. This article explains a research study in which the author worked with four male students to explore how they viewed the concept of masculinity in several different texts. The author used a number of critical literacy strategies when working with these students, leading to deeper discussions of how texts can reflect gender and concepts related to gender. Bibliography Young, J.P., & Brozo, W.G. (2001). Boys will be boys, or will they? Literacy and masculinities. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 316-325. This article sheds light on two researchers’ conversations about literacy and males. The conversations are presented in the form of emails and detail statistical data related to boys’ literacy, as well as behaviors observed over the course of their individual research projects. Through their detailed discussions, they both come to agree that all students – males and females – need adequate critical literacy skills in order to effectively think and communicate in our evolving society.