Engl 3080-Argumentative Writing (argument)

advertisement

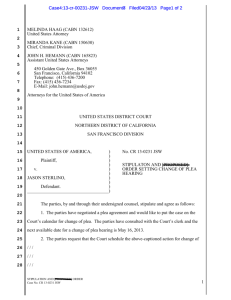

Thompson 1 Brooke Thompson Dr. Lopez ENGL 3080 9 December 2014 The Necessity of Plea Bargaining One of the major controversial topics in the legal sphere, outside of today’s demanding court cases, is the constitutionality of plea bargains and whether or not they are necessary in the criminal justice system. The main argument or larger conversation surrounding this topic is the fact that plea bargaining is essentially unfair, unjust, and primarily unconstitutional. In reality, because plea bargaining is a choice given to defendants rather than a requirement, the plea bargaining system remains constitutional, just as well as it is fair and just. Also, not only are plea bargains constitutional, but they are necessary to the administration of the criminal justice system, for pleas benefit all parties involved. We will discover just how the prosecution, the judge, the defendant, and the court all benefit from the plea bargaining system and why this system still remains in place today. More than 90 percent of criminal cases in America end in a plea deal for a specific reason. Furthermore, we will identify the benefits that result from having the plea system in place, and how the system substantially outweighs the negative prospective of plea bargaining as a means of settling a case. Although the bargaining system may be controversial because of the vast number of cons claimed to be associated with the process, we will see just how it still proves constitutional and most necessary and proper for the balance it provides to the criminal justice system as a whole. Out of the various reasons for the negative outlook on plea bargaining, the two biggest issues are the coercive nature behind accepted plea bargains, and the incompetency of those who Thompson 2 accept the pleas. These two issues lead to a large percentage of innocent defendants who plea out in fear and/or a misunderstanding of their rights. Because several innocent people are being sentenced, it has caused a controversy in the legal system where parties have opted to request a partial ban on pleas, or a request to eliminate the system altogether. Because getting rid of the bargaining method will do more harm than good to the criminal justice system, banning plea deals and suggesting the unconstitutionality of the act has failed significantly. Millions of cases would be overturned if pleas were declared unconstitutional, and the already overcrowded dockets of the American courts will cause a blockage on the availability of courtrooms and judges needed to try each of these cases. Furthermore, the issue with coercion has resulted in cases where the courts ruled on the requirement of counsel, those who can properly advise indigents on the severity of a crime and help them outweigh the costs of a guilty plea, as originally outlined in the Sixth Amendment of the right to counsel. However, because the process of the bargain crucially affects the entire criminal justice system, it fails to be eliminated simply because of negligence. Instead, defense attorneys have a duty to administer assistance to defendants contemplating the acceptance of a guilty plea. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy of the United States Supreme Court wrote in one of his opinions that, “‘The reality is that plea bargains have become so central to the administration of the criminal justice system that defense counsel have responsibilities [. . .] that must be met to render the adequate assistance of counsel that the Sixth Amendment requires’” (Veith). Because the assistance of counsel is available to defendants, there should be no issue with incompetency, unless the defender has failed at his duty of actively providing knowledgeable input on a defendant’s case—which can then be tried in the court of law. Thompson 3 As far as the coercive nature of the plea bargaining system and how it causes factually innocent people to take a plea out of the fear of receiving a harsher sentence in court, has caused several debates on the unjust nature of the plea bargaining system. The idea of a plea is to allow defendants to receive a lesser sentence than they would if they went to trial: “A defendant might plead guilty, not because he is guilty, but because the prosecutor offers some concession in return. Even an innocent defendant may rationally prefer a specified lenient sentence to the risk of a much harsher sentence resulting from a wrongful conviction at trial” (Gazal-Ayal). The simple fact that they would prefer a specified lenient sentence means that they have a choice to choose whether or not to accept a guilty plea in the first place. With a plea, there are three options: guilty, not guilty, and nolo contender, meaning “no contest.” Because there are three choices that can be made when taking a plea, one cannot argue a guilty plea being forced upon if one has the ability to make such a decision of guilt for oneself: “Supporters of the plea bargaining system claim that the above argument [of force] ignores the crux of the practice. Plea agreements are not forced on defendants, supporters note—they are only an option” (GazalAyal). Because they are an option, they remain constitutional. So now not only are there defenders who are designed and delegated to educate their defendants on the nature of a plea, the defendant then has a choice on whether or not to take it. Furthermore, because these two measures are in place, the negative outlook on pleas is justified because of the provisions installed to make the process legal and beneficial—if properly executed. Shifting away from the negative aspect of pleas, let’s focus on why the criminal system needs plea bargaining to remain integrated in the courts. Although plea bargaining is seen as an evil, it’s by far the most necessary evil in the justice system because of the balance it provides to the system at large. The system, with the implementation of pleas, is already overcrowded with Thompson 4 cases that need to go to trial. In reality, the justice system can only supply so many lawyers, judges, courtrooms, and public defense attorneys until they have ran out of the integral elements needed for a defendant to go to trial. For example, in the Supreme Court, “Approximately 10,000 petitions are filed with the Court in the course of a Term [or one year]. In addition, some 1,200 applications of various kinds are filed each year that can be acted upon by a single Justice” (Supreme Court). On average, cases—depending on their severity—can take months for a decision, which costs the courts money for trial materials and attorneys to represent the case. If all 10,000 of these cases went to trial, the criminal justice system would not be able to afford the cost and the man power needed to expedite all cases. Thus, plea bargains play a vital role in the efficiency of the justice system. Out of these 10,000 petitions of writ, the lack of severity for some issues can cause a loss of attention to those cases that need extended time to determine an appropriate outcome. This problem has been prominent for years: “what most concerned Congress, in 1996, was the crowding that it saw on the dockets of the federal courts, with prisoners’ lawsuits piling up and taking longer to decide” (Denniston). Furthermore, in addition to plea bargaining cutting down on time and resources, it cuts down on the number of individuals occupying our already crowded prison cells: “America’s prisons now hold more than 2.3 million inmates, and many of the facilities are overcrowded, with serious implications for both health and safety” (Denniston). For example, “In California, the states’ 33 prisons are operating at almost twice their design capacity — actually, 195 percent, meaning that two inmates have to occupy the space designed for one” (Denniston). Because America’s prison cells are already at maximum capacity from the small percentage of cases heard by the courts, there is no way America will be able to accommodate the number of potential inmates that would result from the lack of plea bargaining. Thompson 5 Furthermore, plea bargaining benefits the criminal justice system by providing conviction rates for prosecutors and allowing them to focus primarily on issues that are more severe: “it enables them to secure high conviction rates while avoiding the expense, uncertainty, and opportunity costs of trials. By obtaining guilty pleas, prosecutors can pursue more cases, potentially resulting in greater aggregate deterrent or incapacitative effects with a finite amount of resources” (Smith). In addition to helping prosecutors focus primarily on more severe cases, plea bargains have the potential to help in the conviction of a co-defendant on trial, if the individual involved in the plea is able to be a witness during trial. In some cases, defendants who take a plea bargain are subject to being a witness as a part of their deal of a lesser sentence; not all plea deals are strictly for lesser sentences alone. For example, over this past summer I worked on a murder case that went to the Fulton County Superior Court where a group of five young, black males—gang affiliated—were indicted on the robbery and murder of Jerrick Jackson, brother of a prominent Atlanta pastor, Wiley Jackson. Out of the five co-defendants, one of the defendants plead at the beginning of the case. Part of his deal was to testify against the other males, detailing what happened during the crime and identifying which individual was responsible for each action that took place during the night of the crime. One of the defendants on trial, Demetrius Morgan, claimed he knew nothing about what the other four planned to do, and plead not guilty. However, “Alejandro Pitts entered a guilty plea before Morgan's trial started. He testified on Monday and said Morgan knew, along with everyone else in the car, what they were about to do” (Harris). Because of Pitts’ testimony, the jury was able come to a proper verdict on each individual involved, based on factual truth. In the instance that testimony is relevant to the conclusion of a case, plea deals prove beneficial to the criminal justice system. Thompson 6 In conclusion, plea bargaining, like every other controversial issue, has both pros and cons that can be debated and misunderstood. Yes, plea bargaining may be seen as unjust, unfair, and unconstitutional, but in reality, it’s quite the opposite. As we have outlined above, plea bargaining has three possible outcomes—guilty, not guilty, and nolo contender—all of which are voluntary decisions that can be made of the accused defendant. Because of the provisions of the Sixth Amendment, giving individuals the right to counsel, the argument that plea deals are forced on innocent and incompetent individuals fails because of the provision that has been set to accommodate them. Yes, there are instances where the defendant is wrongfully advised, and if proven, can be taken to court. But the majority of defendants are given an explanation and a choice. Furthermore, plea bargaining is necessary to the criminal justice system as a whole because it provides a balance in the administration of the courts and in America’s overcrowded prison cells. If the 10,000 petitions of writ, discussed above, were to go to trial versus settled with a plea deal, the criminal justice system would face a true problem, as they would not have the means to address all 10,000 cases. Furthermore, the convenience of plea bargaining helps the prosecution with conviction rates and settling cases properly, like the murder case of Jerrick Jackson. Is plea bargaining an evil? Maybe, but unnecessary—by no means. As proven, plea bargaining plays an integral role in the criminal justice system as a whole. Even though the method of plea bargaining has its downfalls, it has the potential to be improved, as any other evolving structure. However, it should never be partially banned or abolished because of its constitutionality and necessity to our judicial system. Thompson 7 Works Cited “A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court.” Supreme Court of the United States. 9 Dec. 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. Denniston, Lyle. “Argument preview: Crowded prisons, inmates’ rights.” SCOTUSblog. SCOTUSblog, 28 Nov. 2010. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. Gazal-Ayal, Oren, “Partial Ban on Plea Bargains.”. Cardozo Law Review 27 (2006): 2295-2351. SSRN. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. Harris, Rodney. “Demetrius Morgan found not guilty on murder charge, guilty on others in Jerrick Jackson trial.” CBS 46.com. WorldNow and WGCL-TV., 15 July 2014. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. Smith, Douglas A. “Plea Bargaining Controversy, The.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 77.3 (1987): 949-968. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. Veith, Gene. “The constitutional right to a plea bargain.” Patheos Hosting the Conversation On Faith. Patheos, 23 March 2012. Web. 9 Dec. 2014