1ac Know Your Audience Pages 14-23

advertisement

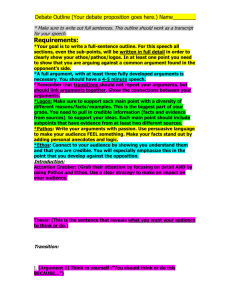

1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 14 Know Your Audience: Use the Basic Academic Structure Introduction: First Paragraph The purpose of the Introductory Paragraph is to act as a “road map” or a guide to the writer’s main claim. It provides background information (Lead-In), states the purpose of the paper (Thesis Statement), and lists the three major routes (Listing of supporting arguments). Intro Paragraph in order: 1)Lead-In 2)Thesis Statement 3)Listing of 3 Supporting Arguments Body: Three Supporting Arguments The purpose of the Body is to prove the thesis through full discussions of each supporting argument. This includes three pieces of evidence per argument accompanied by full explanation/connection. In Short Essays, Each Argument=1 Paragraph In Longer Essays, Each Argument=1Section. Sections=3 or more paragraphs. Each Body Paragraph Contains Nine Structures: 1) Topic Sentence that introduces argument and reinforces thesis 2) Listing of Evidence with brief explanation of argument 3) Provide Evidence #1 4) Explain Evidence #1 5) Provide Evidence #2 6) Explain Evidence #2 7) Provide Evidence #3 8) Explain Evidence #3 9) Reinforce Argument with a Wrap-Up Sentence Conclusion: Final Paragraph The purpose of the conclusion is to summarize the paper and provide lasting resonance. If the introduction is a “road map,” the conclusion is a “rear-view mirror.” A conclusion reflects a reminiscent tone that reminds the readers of the overview, the thesis, and all major points without introducing new information. It ends with a “So-What” sentence (or sentences) that prompt the audience to think about the issue even after they have finished reading the paper. 1)Return to Lead-In 2)Restate Thesis 3)Revisit Major Points & 4) “So-What?” 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 15 Know Your Audience: Identify their Needs Effective collegiate writers possess Audience Awareness. This means knowing WHO you are trying to convince and HOW to convince them. If you do not know your audience, then you cannot reach them. You must connect with your audience in your introduction or you will lose them and they will not read your essay. Identify Your Audience before You Begin Writing Uninterested-- This audience might share different interests or might not think that the topic affects them. Uninformed-- This audience does not possess the basic background information necessary to understand your argument. Unconvinced-- This audience is fundamentally opposed to your argument. Use Your Introduction to Grab Your Readers by Making the Topic- Relatable-- You must make the topic relevant to the audience’s interests. Understandable-- You must provide background information for illumination. Trustworthy-- You must knock down major opposition. Keep Your Audience in Mind throughout the Entire Writing Process The Uninterested Audience--Provide examples that relate to their interests. The Uninformed Audience--Use terminology and examples that are understandable; Explain everything thoroughly. The Unconvinced Audience--Maintain credibility through the use of factual evidence and reliable sources, knock down major opposing arguments, and avoid offensive language. 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 16 Know Your Audience: Plan Your Thesis Statement Step One: Brainstorm & Decide on a topic. Successful academic writing is pre-planned writing. It does not mean that you cannot make changes; it means that you start with the destination in mind, along with the points you are going to use to reach that destination. If you do not know where you are going, how is your reader supposed to follow you there? The way to go about doing this is to think through your feelings about the work when you first read it, your ideas about messages, your connections to greater meanings, and your reactions to the class discussions. Step Two: Make it argumentative. It is not enough just to know your topic. You need to say something unique, original, and argumentative. Step Three: Cut it down to the basic crux of the argument. The basic crux of the argument is the point the writer is proving. The writer should be able to identify the thesis in a short sentence. It does not take long-winded explanations or references (that’s what the paper is for). If the thesis cannot be written in a simple sentence, it is too convoluted for the purposes of 1302 and needs to be finetuned. Step Four: Make sure the thesis fits into one of the three claim categories. SUBSTANTIATION: Cause/Effect Video Games cause violent behavior. EVALUATION: Judgment Scuba Diving is the best form of exercise. POLICY: Recommendation The school should institute a ban on all cell phones. Step Five: Use the Checklist below to make sure that your thesis is solid. Questions to ask yourself Explanations Does it contain SUBSTANTIATION? Does it contain EVALUATION? Does it contain POLICY? A causes B OR B is a result of A Contains some type of judgment Contains should, should not, must, ought to, needs, etc. Is it written in sentence form? NOT a question Is it a full sentence? NOT a fragment or run-on Is it in Active Voice? Follows the Subject, Verb, Object format Is it argumentative? NOT Fact or Opinion Can it be reasonably opposed? NOT an obvious statement Is it written clearly and concisely? Does NOT include “because” Is it logical? NOT a fallacy 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 17 Know Your Audience: Plan Your Supporting Arguments Supporting Arguments are claims that prove the thesis by providing reasons that make it true. STEP 1: Identify the type of claim found in your thesis--Substantiation, Policy, or Evaluation STEP 2: Turn thesis into a question by using HOW or WHY. STEP 3: Answer that question with three different argumentative statements. Substantiation (Cause/Effect): Arguments prove HOW one situation causes the other. Evaluation (Judgment): Arguments explain WHY the judgment is true. Policy (Should/Need/Must etc.): Arguments explain WHY the situation needs to be changed (Horrible State of Current Status). OR HOW the situation will get better if it is changed. OR HOW the situation will get worse if it doesn’t get changed. STEP 4: Use the examples found below to guide your work. SUBSTANTIATION Example Thesis: Horror Movies cause nightmares. Thesis as Question: HOW do horror movies cause nightmares? Answers (a.k.a. Supporting Arguments): ARGUMENT #1: Horror Movies disallow the brain from relinquishing the scary images during dream cycles. ARGUMENT #2: Horror Movies force the psyche to process the on-screen traumatic experiences during sleep. ARGUMENT #3: Horror Movies provoke fight or flight responses from which watchers cannot disengage. EVALUATION Example Thesis: Music is good therapy. Thesis as Question: WHY is music good therapy? Answers: ARGUMENT #1: Music relaxes listeners through sound. ARGUMENT #2: Music provides an outlet for creativity. ARGUMENT #3: Music reflects positive emotions. POLICY Examples Thesis: The United States should implement year round schooling. Thesis as WHY Question: WHY should the U.S. implement year-round schooling? Answers describe Current Status: ARGUMENT #1: Traditional school years do not give students time to achieve high standards. ARGUMENT #2: Traditional school years do not enable students to compete internationally. ARGUMENT #3: Traditional school years do not give students enough rest breaks. Thesis as HOW question: HOW will implementing year-round schooling make things better? ARGUMENT #1: Implementation of year-round schooling will give students time to achieve high standards. ARGUMENT #2: Implementation of year-round schooling will enable students to compete internationally. ARGUMENT #3: Implementation of year-round schooling will give students frequent rest breaks. Thesis as HOW question: HOW will not implementing year-round schooling make things worse? ARGUMENT #1: Not implementing year-round schooling will prevent students from learning material. ARGUMENT #2: Not implementing year-round schooling will force students further behind internationally. ARGUMENT #3: Not implementing year-round schooling will cause student and faculty exhaustion. 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 18 Know Your Audience: Supporting Arguments Cont. STEP 5: Utilize the checklist below to ensure correct construction. Revise accordingly. Requirements for Supporting Arguments All three arguments start with the same subject All three arguments are grammatically parallel Arguments are Written in Active Voice Arguments are Written in Academic Voice Arguments are Argumentative, not Facts or Opinions Arguments are Grammatically Correct Arguments are Clear & Concise Arguments have Reasonable Opposition Arguments support the thesis by answering HOW or WHY Arguments acts as umbrellas that allow for supporting points Arguments are logically sound, not Fallacious Arguments are written as Full sentences, NOT Questions 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 19 Know Your Audience: Use Persuasive Strategies Think of a successful television commercial or ad campaign and ask yourself about the characteristics that make it “stick” with you. The same strategies and techniques used in successful commercial persuasion are similar to the ones we use when crafting written argumentation: Clear Claims Repetition of Major Ideas Music & Language: Solid Sentence Fluency & Compelling Vocabulary Audience Specificity “Sexy” (Interesting & Intriguing) Topics Combination of Appeals Appeals: Writers present material in such a way that audience agreement is attained through the shared experience of logic, emotion, or ethics. Logos (logical): Using the arrangement of facts to lead readers to reasonable conclusions. Ex: The amount of fatal accidents resulting from cell phone usage supports the need to pass legislation limiting usage while driving. Pathos (emotional): Using emotional imagery/verbiage to lead readers to conclusion based upon the experience of those emotions. Ex: The 7-year old boy was on his way to his first baseball tournament when the vehicle in which he was riding was struck by the texting teen driver. He was killed instantly, leaving devastated parents and two grief-stricken siblings. Ethos (ethical): Using morals or ethics shared by the majority of audience members to reach the conclusion that the writer’s assertions are “just” or “right.” Ex: Texas residents should vote for legislation banning texting while driving because it will save lives. 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 20 Know Your Audience: Avoid Common Fallacies Fallacy=A Claim built upon Faulty Logic There are many different types of logical fallacies, so there is no need to attempt to memorize every single possible fallacy. However, it is important that beginning college writers attain some level of recognition of the most common fallacies, so that they can avoid making fallacious claims themselves. Ad Hominem= Attacks the character of the arguer rather than the argument itself Ex: Susie is too young and naïve to make a valid argument as she has not seen the world yet. Bandwagon= Suggests that an argument is true because the majority believes it. Ex: America should stop using the dollar because most of the world has changed to the Euro. Begging the Question=Uses Circular Reasoning to prove a statement. Ex: The mayor is dumb because she’s stupid. Either/Or Reasoning=Oversimplifies the issue by assuming there are only two sides. Ex: Either they serve their country, or they are traitors. Weak Analogy=Assumes truth through the comparison of two unlike items. Ex: A woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle. Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc=Assumes a non-existent cause & effect relationship. Ex: The boy stepped on a crack so his mother broke her back. Hasty Generalization=Uses a part to make an inaccurate claim about a whole. Ex: John is a Democrat and he likes Jay-Z’s music; All Democrats like Jay-Z. Slippery Slope=Suggests that one event will automatically lead to a chain of events. Ex: Buying a foreign car will cause Ford Motor Company to go out of business. Since the ice caps are melting, the world will be engulfed in water. Argument from False Authority=Depends upon an anonymous or non-credible “expert.” Ex: The Frosted Flakes are nutritious because it says it on the box. Non-Sequitur=Does not logically follow the preceding statement or premise. Ex: Gabby Giffords is from Tucson, Arizona so it is important for Arizonans to like NASA. Speaking of dinosaurs, the Alamo is free for all visitors. 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 21 Know Your Audience: Developing & Drafting The Introduction The Introductory Paragraph Contains Three Components IN THIS ORDER: 1) LEAD-IN: SEVERAL sentences that frontload the audience so that they have enough basic background information to understand the claim. 2) THESIS STATEMENT: ONE underlined sentence that succinctly states the claim without providing reasons. 3) LISTING: ONE grammatically parallel sentence that introduces all three arguments & reinforces the thesis FIRST: Profile Your Audience as Uninterested, Uninformed, or Unconvinced. UNINTERESTED ----------maintains other interests/does not think topic affects them UNINFORMED -------------does not possess basic knowledge to understand the thesis UNCONVINCED------------maintains prior opposition to the thesis SECOND: Determine purpose of introduction. UNINTERESTED ----------Must make the topic relevant to the audience’s interests UNINFORMED -------------Must provide background information for illumination UNCONVINCED -----------Must knock down major opposition. THIRD: Choose Specific Strategy for Lead-In. o o o o o Provide the definition of central words or ideas in thesis Provide necessary background (e.g. history of issue or description of current situation) Provide an anecdote that illustrates the current situation Describe a scenario or common scene that illustrates the negatives of the current situation Sympathize with the major opposing argument to your thesis and refute it IMPORTANT NOTE: Do NOT rush the lead-in part of your introduction. It sets up the entire paper by stating the problem, defining the specific area of concentration, and/or providing the purpose for the paper. This is where the writer grabs the audience by directing the issue to their specific needs. The worse thing an academic writer can ever do is leave the audience stopped at the beginning because they do not have enough information to understand the writer's train of thought. When this happens, the argument fails. 1301 Essay Writing Manual Miller-Davis 22 Know Your Audience: Developing & Drafting the Conclusion Return to Overview/Lead-In, Revisit Major Points, Restate Thesis (any order) & a “So-What?” Remember, the Introduction is a Road Map, the Conclusion is a Rear-view Mirror. The most important aspect to remember when writing your conclusion is that the conclusion acts as a rear-view mirror of the entire paper. The audience has already completed the journey of your paper. It is now time for you to remind them of all they have seen and experienced without merely repeating it. When you want someone to remember how great your argument is so that they believe it, you must first bring them full circle to the beginning, remind them of all of the major points, reinforce the argument in direct and specific terms, and then end by leaving them with something that creates lasting resonance. Return to Lead-In: Make sure you bring readers full circle by providing some type of follow-up to the situation you described in the initial sentences of your introduction. If you provided a scenario, return to that scenario. If your overview states the problem, you can remind the reader that the problem needs to be remedied or you can imagine a scenario where the solutions proposed in your paper have solved the problem. Or if your overview provided general background information, you can simply refer to that basic knowledge by reminding reader that it exists. Revisit Major Points: Remind reader of all major arguments by discussing each argument briefly. Usually this takes 1-2 sentences. Sometimes, it might be wise to bring up one of the points within each argument that was particularly convincing. Other times, you can just relist each argument and remind the audience how each argument proves the thesis. Restate Thesis: You should not restate the thesis exactly as you did in your introduction, but you should use a synonymous phrase that echoes the exact sentiment. In other words, the premise of the argument should NOT have changed by the time you get to the end. Provide a “So-What?”: Your issue should be so important to you that you want the audience to think about it long after they have finished reading your paper. Usually, this is done by making a statement about the significance of the argument to the reader (without saying “you” of course). As a writer, you want to make a final statement that creates lasting resonance for your reader. How do I create lasting resonance? The following directions are only guidelines to help spur your thinking, they do NOT describe the only ways in which a “so-what?” can be constructed. If the thesis is a policy claim: Make a generalized statement about the future ramifications if the policy is not adopted. If the thesis is a substantiation claim: Make a point about what would happen if the pre-cursor did not exist. If the thesis is an evaluation claim: Make a general comment about the future good or the future harm of the subject.