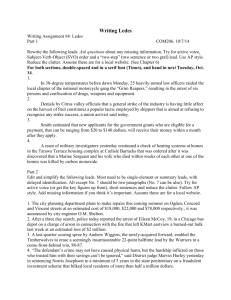

Building the Feature Story

advertisement

Building the Feature Story

Senior Projects – 2014-15

What is a Feature Story?

A feature story is a special human

interest story or article that is not

closely tied to a recent news event. It

focuses on particular people, places,

and events, and it goes into great detail

regarding concepts and ideas of

specific interest.

Elements of Feature Stories

direct quotation: A report of the exact words of an author or speaker. Unlike

an indirect quotation, a direct quotation is placed inside quotation marks.

Example:

"She quoted from a letter [E.B.] White wrote in 1981: 'You might be amused

to know that Strunk and White was adapted for a ballet production recently.

I didn't get to the show, but I'm sure Will Strunk, had he been alive, would

have lost no time in reaching the scene, to watch dancers move gracefully to

his rules of grammar.'“

(Jeremy Eichler, "Style Gets New Elements." The New York Times, October

19, 2005)

Elements of Feature Stories

indirect quotation: A paraphrase of someone else's words. Also called

indirect discourse. An indirect quotation (unlike a direct quotation) is

not placed in quotation marks.

Example:

Military relations with China also are tough, said U.S. Navy Admiral

William Fallon, commander of the U.S. Pacific Command. He said he

called Chinese counterparts to discuss North Korea's missile tests, for

example, and got a written response that said, in essence, “Thanks, but

no thanks.”

(Alwyn Scott, "U.S. May Slap China With Suit in Intellectual-Property

Dispute." The Seattle Times, July 10, 2006)

Elements of Feature Stories

The combination of direct quotation and indirect quotation is called

mixed quotation.

Example:

"In the process of verbally dismantling the quantification of higher

education, [Leon Botstein] compared Ivy League universities to Gucci

handbags and sneaked in concise dismissals of the College Board

('offensive, essentially'), the college essay ('an awful genre'), the S.A.T.

('a totally useless event'), and multiple-choice tests in general ('a grave

error in the name of so-called objectivity')."

(Alice Gregory, "Pictures From an Institution." The New Yorker,

September 29, 2014)

Elements of Feature Stories

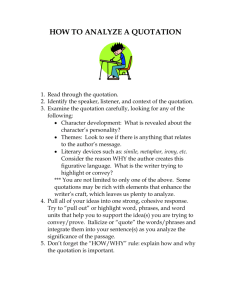

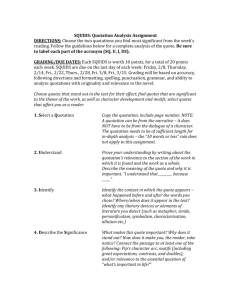

When Are Quotes Worth Quoting?

• when they put words before the

reader for close analysis

• when they are crucial evidence

• when they say something so well it

can't be said better.

(Bill Stott, Write to the Point. Anchor

Press, 1984)

Elements of Feature Writing

• Support and Elaboration consist of the specific details and

information writers use to develop their topic. The key to developing

support and elaboration is getting specific. Good writers use concrete,

specific details, and relevant information to construct mental images

for their readers. Without this attention to detail, readers struggle to

picture what the writer is talking about, and will often give up

altogether.

• Two important concepts in support and elaboration are sufficiency

and relatedness.

Elements of Feature Writing

Sufficiency refers the amount of

detail — is there enough detail to

support the topic?

Sufficiency, however, is not

enough. The power of your

information is determined less by

the quantity of details than by their

quality.

Elements of Feature Writing

Relatedness refers to the

quality of the details and

their relevance to the

topic.

Good writers select only

the details that will

support their focus,

deleting irrelevant

information.

Elements of Narrative Writing

• Characters: All stories must have

characters, or the people or subjects

of the story.

• Plot: Every story needs a plot, or

events to give the characters

something to react to. Usually, the

plot consists of five components: the

exposition, rising action, climax,

falling action, and resolution.

Elements of Narrative Writing

• Conflict: A conflict is any struggle

between opposing forces. Imagine a

story where there were no problems.

Usually, the main conflict is between the

protagonist and the antagonist, but that

is not always the case. The struggles can

exist between society, within a character,

or even with acts of nature.

• Setting: The setting is the time and the

location in which the story takes place.

The conflict IS the setting! Ingenious!

Basic Feature Structure

• Lede

When Scott Storch was 8 years old, he was dizzied by a soccer

cleat to the head. His mom did not take such injuries in stride…

Mom banned Scotty from participating in sports. Instead, she

enrolled him in piano classes at Candil Jacaranda Montessori in

Plantation, about 15 minutes from their Sunrise home. An old

jazz pianist named Jack Keller taught him.

• Nut graf

At age 33, in 2006, his fee hit six figures per beat, which he

could produce in 15 minutes. The money turned the Sunrise

kid into a Palm Island Lothario. Hip-hop's blinged-out white

boy lived in an expansive villa in the Miami Beach enclave,

kept more than a dozen exotic vehicles — including a $1.7

million sports car — and docked a $20 million yacht.

Basic Feature Structure

• Captivating descriptions

• Direct quotes

• Indirect (summary) quotes

• And transitions connecting everything…

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that capture mood:

• The blue wall on the left side of the room brings a sort of serenity to

the classroom. (P. 1)

• Although the room is so bright, it’s gloomy in here. The only bright

part is my friends. (P. 1)

• The Eeyore stuffed animal and drawing remind me of my childhood,

and all the Disney movies I’ve watched and loved over the years. (P. 2)

• The worn old desks that have been etched after years of students

complement the teacher’s podium that is a dirty and disgusting tone

of wood. The white boards are faintly smudged with the writings of

purple, blue and orange; tape separates them and has also been

worn. The walls and chalk stands are a pleasant shade of puke which

ties the room together. (P. 2)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey mood:

• The ceiling has many holes, like gunfire has broken out and the only

place to shoot is up… Big windows share a false hope of reaching the

outside world, yet the locks on them symbolize our captivity. (P. 2)

• The room where you need to arrive early in order to secure a

comfortable chair. The room where the tables seem to always be

wobbly. The room that is always a bit too warm. (P. 3)

• The lights are turned off and the luminescent glows of cell phones

light up some of the students’ faces, uninterested in the video being

shown. (P. 3)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey mood:

• The whiteboard is the center of attention and the visible, but erased

lessons of last semester are the only remnants of notes we seniors

may have missed due to the stress and preoccupation of college

applications. (P. 3)

• I see the leaves of the trees dancing with the wind. (P. 4)

• As the soft breeze kisses my cheek and the warm sun calms my soul, I

feel free from the oppression that the other sections of this place

creates. (P. 4)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey mood:

• The senior tree looks dead and blue. There is gum all over the ground

and a blue-grey sky. There is not one leaf. (P. 4)

• The gated, secluded playground is empty, but the quad is crowded

with other students. (P. 4)

• Green tables sit on cold broken concrete, infested with blots of black

gum. (P. 4)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that capture sensory detail:

• You hear the rustle of backpacks as students get ready to leave and

start piling by the door. (P. 1)

• The great big windows show the sunrise and the beginning of the day

is starting. (P. 1)

• The rickety chairs rocking back and forth, the tables moving forward

with the push of arms. Whiteboard filled with rainbow writing,

noting homework or assignments. The black tables highlight the

crisp, white binder paper. The air filled with the feet smell of A Hall

mixed with the breakfast numerous students enjoy. (P. 1)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey sensory detail:

• Wheely chairs squeaking on the tile floor – click click clack boom. (P. 2)

• Shelves filled with books, white boards filled with words, and desks

filled with students. (P. 3)

• At the head of the classroom, old and new technology are used to

teach. Combinations of whiteboard and markers fill most of the front

wall where the assignments can be read from afar, with a Smart Board

that projects PowerPoints to show pictures and videos to give fresh

insight about literature and the world, streamed from a school-issued

laptop. (P. 3)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey sensory detail:

• I smell the grass that was cut the day before and the cleaning supplies

used around campus. (P. 4)

• Instead of seeing the white gulls, there are black crows in the

branches of the tall trees. The branches are unusual; they remind me

of blood vessels. The air is slightly chilly, but strangely the warm sun

feels good on my back. (P. 4)

• The wind continues to ease and rage back up again as if it were like a

wave – slowly building up and pulling away from the shore. But then,

all at once, the wave crashes violently into the shore again. (P. 4)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that present narrative:

• The walls are pale and bare, but as the year goes on, they slowly fill with

projects we have worked on. (P. 1)

• The walls are lined with experiences and soon-to-be experiences,

motivation and hard work. (P. 3)

• The chairs make no attempt to match, and appear to come from all walks

of life. (P. 3)

• The senior tree sees all and hears all. No one listens, though. The tree

sees break-ups and get-togethers, people becoming friends and friend

break-ups. Fights and bullies. Kissing. It also sees all of the birds: black

birds, sea gulls and even the painted eagle on the ground. (P. 4)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey narrative:

• This class is a bunch of random pieces combined, so different and

unique that when you take a step back, it all works together. Bare in

the beginning, and now covered with works we all created, gives it a

sense of “meant to be.” People you wouldn’t normally talk to can

now complete your sentences. (P. 3)

• All the posters and pictures on the wall mean so many different

things, each one with its own story. And I always glance at the clock

on my left above the door, slowly watching the time pass by as I write.

(P. 3)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey narrative:

• I see a poster about schizophrenia. There are too many pictures to

take in all at once. I look at the one in the middle left. It is a kid

looking at his mirror image, but the image he sees is cynical and dark.

The middle one is a girl sitting in the dark while hands are shadows in

the background. I begin to feel paranoid. My heart begins beating

faster. I think about memories I have watching scary movies. I am

reminded of an old movie I watched when I was a kid. I almost feel

scared, but I also feel intrigued about how the images I am looking at

right now bring me back to a past experience. (P. 2)

Step 1: Setting the Stage

Descriptions that convey poetry:

Baby blue

if you knew

This room was

covered by the color of the mood.

Tiles – misplaced

Thoughts – erased

left aside

by peers and minds

Cuz sandpaper sighs

engrave a line

to the soul’s pride

where I derive (P. 2)

Step 2: Identifying Direct Quotes

Look for quotes that not only tell the story, but capture the voice of

your interviewee:

"Are you married, my dear?"

"Yes, I am."

"Then you won't mind zipping me up."

Zipped up, Dorothy Parker turned to face her interviewer, and the

world.

Step 3: Choosing Indirect Quotes

• Which quotes would work better as

summaries?

• In creating summary quotes, incorporate

other descriptive details – what the

interviewee said, the tone of his/her

voice, or what he/she was watching

while speaking.

Step 3: Choosing Indirect Quotes

FRANK SINATRA, holding a glass of bourbon in one hand and a cigarette in

the other, stood in a dark corner of the bar between two attractive but

fading blondes who sat waiting for him to say something. But he said

nothing; he had been silent during much of the evening, except now in this

private club in Beverly Hills he seemed even more distant, staring out

through the smoke and semidarkness into a large room beyond the bar

where dozens of young couples sat huddled around small tables or twisted

in the center of the floor to the clamorous clang of folk-rock music blaring

from the stereo.

--Gay Talese, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”

Step 4: Structuring the Feature Story

• The simplest feature structure is the “quote” – summary description –

“quote” – summary description model, in which direct and indirect

quotes are alternated to tell a story.

• Your structure will be determined in part by the story you wish to tell.

In “Obama’s Way,” Michael Lewis alternates the story of President

Obama’s daily activities with the story of Air Force navigator Tyler

Stark, trapped in Libya – using one particular example to illustrate the

power and importance of the presidency.

Step 5: Building the nut graf

• Your nut graf – usually the second or

third paragraph in the story – explains to

the reader why, “in a nutshell,” your

story is important.

• In this case, you’ll be explaining the

importance of this particular interview

or visitation to your senior project

overall.

Step 5: Building the Nut Graf

Christian singles have coffee hour. Young Jews have JDate. But many Muslims

believe that it is forbidden for an unmarried man and woman to meet in

private. In predominantly Muslim countries, the job of making introductions

and even arranging marriages typically falls to a vast network of family and

friends.

In Brooklyn, there is Mr. Shata.

Week after week, Muslims embark on dates with him in tow. Mr. Shata, the

imam of a Bay Ridge mosque, juggles some 550 "marriage candidates," from

a gold-toothed electrician to a professor at Columbia University. The

meetings often unfold on the green velour couch of his office, or over a meal

at his favorite Yemeni restaurant on Atlantic Avenue.

Andrea Elliott of The New York Times

Step 5: Building the Feature Lede

• Feature ledes often begin by setting a scene or painting a picture - in

words - of a person or place.

• A feature lede is often described as a conversation that anyone would

like to be a part of.

• An easy way to begin a feature lede is to visualize that you are telling

your reader a story. You would never start a story with ‘’One hundred

sailors were cast ashore’’. You might begin with something like, ‘’A

merchant ship was sailing in the calm waters of the Indian Ocean, and

suddenly, a storm hit.’’

Types of Ledes: Anecdotal

Anecdotal: Everyone loves a good story. Interesting stories, metaphors

or events make for a riveting read.

• Tells a story

• Creates a situation and draws the reader in

• Provides characters and/or situations with which the reader can

identify

• Usually includes description

Types of Ledes: Anecdotal

BEIJING — The first sign of trouble was powder in the baby’s urine. Then

there was blood. By the time the parents took their son to the hospital, he

had no urine at all.

Kidney stones were the problem, doctors told the parents. The baby died on

May 1 in the hospital, just two weeks after the first symptoms appeared. His

name was Yi Kaixuan. He was 6 months old.

The parents filed a lawsuit on Monday in the arid northwest province of

Gansu, where the family lives, asking for compensation from Sanlu Group,

the maker of the powdered baby formula that Kaixuan had been drinking. It

seemed like a clear-cut liability case; since last month, Sanlu has been at the

center of China’s biggest contaminated food crisis in years. But as in two

other courts dealing with related lawsuits, judges have so far declined to

hear the case.

Edward Wong of The New York Times' Beijing bureau

Types of Ledes: Descriptive

Descriptive ledes: They describe a place, person or an event with great

care so the reader can envision where the story takes place or what

would have happened.

• Conjures up a mental picture of a subject or event

• Helps portray the mood and setting

• Allows the reader to hear, see, smell, feel the situation

Types of Ledes: Descriptive

The fragrance of chicken filled

the air. Yellow broth trickled

down from a stained white

table onto a candy wrapper

covered floor. The custodian

scoffed at the mess, then

wiped it away into an already

full garbage can.

Just another day in the

cafeteria.

The joy of dishes

Types of Ledes: Narrative

• Narrative ledes: Similar to descriptive leads but use strong action

verbs and sometimes even dialogue to make narration effective or to

recreate situations powerfully.

Types of Ledes: Narrative

It was a hell of a time to be in Iceland, although by most accounts it is

always a hell of a time to be in Iceland, where the wind never huffs or

puffs but simply blows your house down. This was early in August, and

it was stormy, as usual, but the summer sun did shine a little, and the

geysers burped blue steam and scalding water, and the glaciers

groaned as they shoved tons of silt a few centimetres closer to the sea.

On the water, the puffins frolicked, the hermit crabs frolicked, and

young people bloated with salmon jerky and warm beer barfed politely

into motion-sickness buckets on the ferry sailing across Klettsvik Bay.

Susan Orlean, “Where’s Willy?” The New Yorker

Types of Ledes: Contrast

• Used when there is a comparison to be made

• Points out opposites and extremes

There were no chemicals, but there certainly was chemistry. There

were no test tubes, but for sure there was experimenting. And a lot of

mixing — and learning — took place in these labs. Jazz labs, that is.

Types of Ledes: Suspended Interest

• Arouses the reader’s curiosity because it doesn’t tell all

• Tempts the reader to read on to find out; sometimes teases

• Usually presents the point near the end of the lede

• Direct opposite of the summary lede

Types of Ledes: Suspended Interest

Working during school. Working after school. Spending free periods

working.

Doesn’t sound like fun, does it?

It is publishing a newspaper, a job that is challenging, ongoing, not

always fun, but rewarding when the final product is distributed.

Types of Ledes: Allusion

• Referring to someone or something well-known

• Can be reference to literature, history, a motto, a quote, a familiar line

in a song or book, the name of a movie, a poem, etc.

• Make sure the reference is suitable to the subject of the copy

The old saying, ‘It’s not whether you win or lose but how you play the

game,’ was a lesson the JV volleyball team learned quickly.

Ledes to Avoid: Quotes

• Unless the quote is exceptional, it isn’t the most original or exciting

way to start your story.

• The quote must set the stage for the copy or give the focus or theme

of the copy

“I wish I could get more money for less work,” senior Amanda Weller,

who is presently working at Shoprite, confessed. It was a feeling

expressed by many, with student expenses rising and limited working

time available.

Ledes to Avoid: Questions

What must a feature lead start with? Certainly not questions. ‘Did you

knows’ and rhetorical questions make for bad sentences and are hardly

interesting.

Rating albums ‘R’ or ‘PG’? A practice unheard of, yet it almost became

a reality when 25 recording companies agreed to comply — to a limited

extent — with the wishes of the Parent Music Resource Center.

Step 6: Tying it All Together with Transitions

• Words and phrases that connect one idea to another

• Often highlight the logical order of ideas

• You can also create transitions by repeating main words and using

well-chosen synonyms and pronouns throughout the paragraph.

Step 6: Tying it All Together with Transitions

Begin tracing your family history by getting a large looseleaf notebook

and making a chart. Then visit old relatives and get them to talk about

their parents, grandparents, aunts, where they came from, when they

married, maiden names, family traditions, and so on. You can also try

to get your hands on old family Bibles, diaries, letters and account

books.

Judith Chasek

Other Transition Methods

For years now on the mud flats on the east side of San Francisco Bay,

artists and ordinary people have been creating imaginative sculptures

by nailing together driftwood and debris. These sculptors build trains

and ballerinas, chickens and totem poles, whales and airplanes with

wood, hubcaps, old tires, rusty cans and whatever washes ashore.

J. Fritz Lanham