Fittipaldi Gabby Fittipaldi Professor Courtright Paper One 29

advertisement

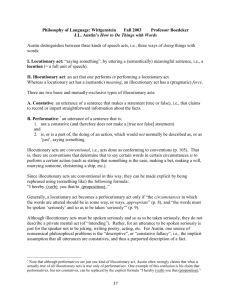

Fittipaldi 1 Gabby Fittipaldi Professor Courtright Paper One 29 September 2014 Speech Acts Day in and day out, sometimes intentionally but often mindlessly, people everywhere welcome, question, praise, demand, and even insult one another. When individuals speak, they utter certain words to produce these sorts of thoughtless results or acts. Acts executed from the process of speaking are formally known as ‘speech acts’ (Sadock). Speech acts are considered to be the minimum or “basic unit of communication” that takes place between individuals (Jaworowska). In other words, these acts, or performances, are how people communicate with one another. They are how speakers get their messages across to the recipients, or listeners. According Searle, a communications theorist, there are three different types of speech acts: locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts, which will be explained in more depth. Each of these three parts contributes to the foundation of the speech acts theory. They are performed in everyday interpersonal conversation and implemented subconsciously by speakers all over the world. Individuals utilize speech acts based on their upbringing and ethnic background; therefore, speech acts differ from country to country. These acts are not universal; they are based on cultural influences and language. In order to grasp a general knowledge of speech acts, one must understand the meanings of the three types. First, there are locutionary acts. A locutionary act indicates what an utterance is in the traditional sense; it is the physical performance of an utterance. Fittipaldi 2 Second, there are illocutionary acts, which indicate what the utterance does. For example, an utterance can be a warning, an assertion, an apology, an approval, a command, and more. It is the effect of an utterance. Searle said, that in order “to perform illocutionary acts [one has] to engage in a rule-governed form of behavior” (“What Is A Speech Act” 222). There are two types of rules that follow illocutionary acts: regulative rules and constitutive rules. Regulative rules “regulate” activities, but they are independent of one another. For example, “when cutting food hold the knife in the right hand” (224). In this example, this act is not dependent on the rule itself. Constitutive rules, on the other hand, define forms of behavior. The existing activity is dependent on these rules or guidelines. For example, “a touchdown is scored when a player crosses the opponents’ goal line in possession of the ball while a play is in progress” (224). In order for one to gain a touchdown, this rule must comply with the activity. Illocutionary acts, altogether, correspond with both of these rules (225). Furthermore, there is still one last type of speech act to mention. Perlocutionary acts are the last type of speech act performed in a conversation. These indicate the effect the utterance has on a listener, and it is what he or she responds with. Through the performances of a perlocutionary act, the speaker influenced the listener to realize or do something. All three of these acts mentioned can be exemplified in everyday communication, including Craig and Tracy’s B-K conversation. In the B-K conversation, a minor example can be provided to clarify these three speech acts. On page 305, lines 021 to 025, B and K talk about buying their fathers Christmas presents. B states how her father is “the main problem,” and K agrees explaining how her dad is the same way. B says, “I think we’ve got the same father,” making an Fittipaldi 3 assertion jokingly, which is the illocutionary act. Her statement itself is the locutionary act. K then responds with, “I think everybody’s father must be like that at some point” (Craig and Tracy). B’s assertion allowed K to ‘realize’, in her opinion, that all dads are the same, thus responding how she did, which is the perlocutionary act. This situation is just one example of how speech acts take place in typical conversations between people. As shown, speech acts are carried out all the time in the utterance of sounds the speaker makes. In Searle’s “What Is A Speech Act,” he says, that theses sounds, or “marks” that one performs are said to have “meaning” (228). “To say that A meant something by x is to say that ‘A intended the utterance of x to produce some effect in an audience by means of the recognition of this intention,’” which is called meaning (228). A particular meaning can be indirectly or directly expressed to the listener; however, there are complications with indirect speech acts. The problems that may arise from indirectly stating something come from the speaker’s utterances. It is possible for him or her to say one thing but mean something else (“Indirect Speech Acts” 60). For this reason, culture plays a significant role in indirect speech acts. Communicative performances are subject to different interpretations based on a listener’s background, native language, and upbringing. “Speech acts are difficult to perform in a second language because learners may not know the idiomatic expressions or cultural norms in the second language…” (CARLA). This contradicts any opinion on speech acts being “universal” because listeners usually apply their first language rules and norms to these types of situations. For example, American and Chinese cultures are different from one another in interpreting utterances. If an American said “I couldn’t agree with you more,” it means that individual liked another’s opinion. However, a native from China Fittipaldi 4 would interpret the utterance as the American not fully agreeing with what he or she said, and thus misconceiving the meaning (CARLA). People tend to speak in idioms and colloquialisms in everyday conversation, which could be confusing to someone of a different cultural environment. In the B-K conversation, there are examples of idioms that are geared towards an American listener and may be understood differently if expressed to a non-American. On page 315, B is describing rural Philadelphia to K. At line 237 B says, “I mean it’s not – doesn’t hold candle to Virginia for example…” (Craig and Tracy). ‘Doesn’t hold a candle to…’ is an idiomatic expression meaning someone or something is not equal and not able to measure up to someone or something else. This is a common idiom, in English, that may not be translated properly or presented in a way that Americans intend for it. Another example to point out in the B-K conversation is on page 316. On this page, B and K are discussing horseback riding and the riding club. At line 257, B is explaining the ride itself and mentions, “If you go over a fence and fall or anything like that… [it’s] seen particularly – in a bad light if you go around a jump instead of going over it” (Craig and Tracy). ‘In a bad light’ is another idiomatic expression that means to make someone seem like a ‘bad’ person. Therefore, B was saying if you jump over the fence and fall, or go around it, you are seen as a coward and weak, i.e. ‘bad.’ To reiterate, an individual raised from another cultural background, and an alternative language, would interpret a saying like that differently. Speech acts are not universal, and this is seen through a variety of examples of oneon-one interaction between English speakers and non-English listeners. As explained previously, there are rules involving speech acts. Rules from one culture and language Fittipaldi 5 group may contrast to another culture and language group, thus leading to different communication norms for both parties (Nelson, Bakary, and Batal 110). If the two groups have different rules for communication and speech acts, the listener, for example, could believe the speaker was being rude. A bilingual listener must learn how to determine when a speech act is being used and, based on the patterns of those particular languages, how a speaker utters the act. Speech acts are a part of everyday communication between people. They are considered the basic unit of communication because in order for one to converse, they have to perform these acts. There are three different types of acts, locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary, and rules for these performances as a whole. However, when two people from two different parts of the world interact with one another, misunderstandings and misinterpretations are inevitable. If speech acts were universal, people would be able to comprehend one another perfectly without the meaning being misconstrued. Since this is not the case, these subconscious speech acts cannot be ubiquitous; therefore they vary from culture to culture based on the rules of that particular language. Fittipaldi 6 Works Cited Craig, R. T., and K. Tracy. “Appendix: The B-K Conversation.” Conversational Coherence. Ed. R. T. Craig & K. Tracy. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1983. 299-320. Print. Jaworowska, Joanna. “Speech Act Theory.” California State University, Los Angeles. Trustees of the California State University, 2004. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. Nelson, Gayle, Waguida El Bakary and Mahmound Al Batal. “Egyptian and American Compliments.” Speech Acts Across Cultures. Ed. Susan M. Gass and Joyce Neu. New York: Mounton de Grayter, 1996. 109-128. Print. Sadock, Jerrold. “Speech Acts.” Division of the Humanities: The University of Chicago Division of the Humanities, n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014. Searle, John. “Indirect Speech Acts.” Syntax and Semantics Vol. 3. Ed. P Cole & J. L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press. 1975. 59-82. Print. Searle, John. “What Is A Speech Act?” Philosophy in America. Ed. P. Cole & J. L. Morgan. London: Allen & Unwin, 1965. 221-239. Print. “What is a Speech Act?” CARLA: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. The University of Minnesota, 2014. Web. 22 September 2014.