Philosophy of Language: Wittgenstein

advertisement

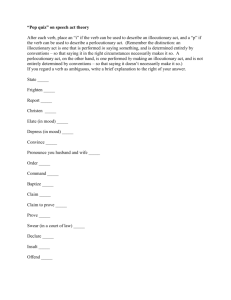

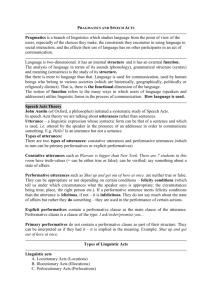

Philosophy of Language: Wittgenstein Fall 2003 Professor Boedeker J.L. Austin’s How to Do Things with Words Austin distinguishes between three kinds of speech acts, i.e., three ways of doing things with words: I. Locutionary act: “saying something”, by uttering a (semantically) meaningful sentence, i.e., a locution (= a full unit of speech). II. Illocutionary act: an act that one performs in performing a locutionary act. Whereas a locutionary act has a (semantic) meaning, an illocutionary act has a (pragmatic) force. There are two basic and mutually-exclusive types of illocutionary acts: A. Constative: an utterance of a sentence that makes a statement (true or false), i.e., that claims to record or impart straightforward information about the facts. B. Performative:* an utterance of a sentence that is: 1. not a constative (and therefore does not make a [true nor false] statement) and 2. is, or is a part of, the doing of an action, which would not normally be described as, or as ‘just’, saying something. Illocutionary acts are conventional, i.e., acts done as conforming to conventions (p. 105). That is, there are conventions that determine that to say certain words in certain circumstances is to perform a certain action (such as stating that something is the case, making a bet, making a will, marrying someone, christening a ship, etc.). Since illocutionary acts are conventional in this way, they can be made explicit by being rephrased using (something like) the following formula: “I hereby (verb) you that/to (proposition) .” Generally, a locutionary act becomes a perlocutionary act only if “the circumstances in which the words are uttered should be in some way, or ways, appropriate” (p. 8), and “the words must be spoken ‘seriously’ and so as to be taken ‘seriously’” (p. 9). Although illocutionary acts must be spoken seriously and so as to be taken seriously, they do not describe a private mental act (of “intending”). Rather, for an utterance to be spoken seriously is just for the speaker not to be joking, writing poetry, acting, etc. For Austin, one source of nonsensical philosophical problems is the “descriptive”, or “constative fallacy”, i.e., the implicit assumption that all utterances are constatives, and thus a purported description of a fact. * Note that although performatives are just one kind of illocutionary act, Austin often wrongly claims that what is actually true of all illocutionary acts is true only of performatives. One example of this confusion is his claim that performatives, but not constatives, can be replaced by the explicit formula “I hereby (verb) you that (proposition).” 37 III. Perlocutionary act: the production, by performing an illocutionary act (and thus also a locutionary act), of certain consequential effects on the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience, or of the speaker, or of other persons (perhaps with the design, intention, or purpose of producing them). Unlike illocutionary acts, perlocutionary acts are not (entirely) conventional. That is, the act performed (on the audience or the speaker) is not determined just by circumstances, speaker, and the words uttered. For example, my performance of the illocutionary act of stating that America is bombing Afghanistan might make one person elated, but another depressed. Or George Bush’s speech might convince one person that he was right, but convince another person that he is a fool. Since perlocutionary acts are not conventional in the way that illocutionary acts are, they cannot generally be made explicit in the way that illocutionary acts can. For example, I cannot perform the perlocutionary act of saying something that makes someone feel better by saying “I hereby make you feel better by saying that…” What does this have to do with Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations? 1. In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein commits what Austin calls the “descriptive”, or “constative” fallacy: assuming that all meaningful use of words is ultimately a matter of saying that this is how things are (Tractatus 4.5). Austin follows the later Wittgenstein in broadening the view of language beyond its merely descriptive use to all sorts of uses (PI sections 134-136). Whereas Wittgenstein is skeptical about the project of making general descriptions of language (PI sections 64-67), however, Austin’s distinctions between locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts is an attempt to do just this. 2. Wittgenstein claims: “For a large class of cases – though not for all – in which we employ the word ‘meaning’ it can be explained [note different translation!] thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language” (43; cf. 30, 138, 197). But this guideline that “meaning is use” can also prove misleading. Whereas locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts are all uses of words, only locutionary and illocutionary acts really deserve to be called uses that involve (semantic or pragmatic) meaning, since only these acts are entirely governed by conventions. Perlocutionary acts, however, are uses of words that go beyond their (semantic or pragmatic) meaning, since they are not entirely governed by conventions. Response paper topic for John Searle’s Speech Acts: Explain Paul Grice’s theory of meaning, Searle’s criticism of it, and (in rough terms) Searle’s alternative account. What important addition does Searle make to Grice’s theory? 38