view ppp [PPT 0KB]

advertisement

![view ppp [PPT 0KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/009985608_1-d805f754ff4bfa46d3b75b7b352c4275-768x994.png)

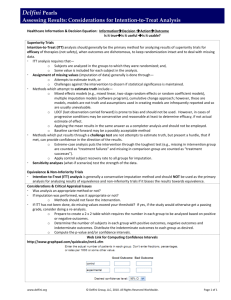

Are you still feeling lucky punk? Why Ken Henry’s hunch is right – we should abolish dividend imputation and cut company tax to 19% Nicholas Gruen Presentation at ANU Canberra, 14th April 2009 Outline 1. 2. 3. Introduction Our current situation “are we still feeling lucky?” The case for lower company tax – – 4. ‘Long clean lines of policy’ – – 5. In a closed economy In an open economy Alignment Dividend imputation Conclusion Our Circumstances Our Circumstances “After all, Indonesia’s current account deficits had been nowhere near as large . . . as its neighbours’ – at less than 4 percent of GDP, Indonesia’s . . . deficit was actually smaller than, say, Australia’s.” Paul Krugman on Indonesia’s economic crisis Our Circumstances Australia’s current account deficits have been around 6% and may rise to 9% New Zealand has been in this situation for some time and is now on S&P watch for credit downgrade We need to – Ensure we can attract the funds we need to make it through the next few years – Maximise extent to which recovery is investment driven – Establish long term plans to increase savings Tax is about choices Except for taxing economic rent and ‘bads’, taxing is costly. So . . . • ‘Long clean lines’ of policy are valuable, but also come with costs. – ‘Real reform’ - getting top rate down – versus ‘tinkering’ of lifting thresholds – The argument for alignment of company and top personal tax – Dividend imputation was a ‘long clean lines’ reform • None of these issues can or should be decided in principle • We must choose the lesser of evils based on the evidence in specific cases. Capital taxation – Other things being equal it’s more economically costly than taxation on personal exertion – Why? • The implicit tax on saving and investment compounds over time (the closed economy argument) • Capital is more mobile than – even highly skilled – people (the open economy argument) The closed economy argument – Mankiw and Weinzierl’s ‘back of the envelope’ model – A simple neoclassical growth model of the US with plausible parameterisation and 25% tax on labour and capital – In context of debates about extent of self funding of tax cuts • Where are various taxes on the Laffer Curve? – Conclusions are that in the long run • Capital tax cuts are nearly 50% self funding through higher saving and investment compounding through time • Labour tax cuts are less than 20% self funding – through greater work effort Delong on the closed economy argument • I very much fear that our current system of capital [taxation] leaves not just $20 bills on the sidewalk but $1000 bills • If there are important labor rents earned by workers in capital intensive industries then the excess burden from capital taxation will be magnified and will fall on the fortunate rent-sharers in labor as well. • If total factor productivity does not fall from the sky but is instead linked to investments in any of a number of ways, then any capital tax that reduces investment will reduce productivity growth as well (Do we really believe that technological progress in making computers was independent of investment in information technology?) • Then by how much would more capital-friendly tax policies in the 1970s and 1980s that encouraged investment, including investment in information technology, have brought forward in time the high-tech productivity boom of the 1990s and 2000s? . . . • This paper's estimates of growth effects and revenue offsets are more likely to be low than high. The closed economy argument – Arguments only slightly weakened with • Non-infinite time horizon for household savings decisions • Recovery of lost revenue by alternative (distortionary) taxes. – Arguments are greatly strengthened if • Capital investment has positive externalities related to technology development and transfer as has been suggested by DeLong and others • The economy is open to capital flows • Capital taxation cuts could be less regressive The open economy argument: Tax and foreign investment A substantial body of research considers . . . the effects of taxation on investment and on tax avoidance activities. . . . The first generation of these studies . . . reports tax elasticities of investment in the neighborhood of –0.6. [So] a ten percent tax reduction (for example, reducing the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 31.5 percent) should be associated with six percent greater inbound foreign investment. More recent evidence suggests that foreign direct investment is even more tax sensitive than this. Hines, J and Summers, L, 2009. “How Globalization Affects Tax Design”, NBER Tax cuts and growth - empirical evidence – Lee and Gordon (2005) • Strong negative correlations between company tax rates and economic growth – 10 percentage point cut in the company tax rate increases per capita annual growth by between 0.57 and 1.82 percent • Little or no correlation between top personal tax rates and economic growth – Hassett and Mather (2006) • Strong negative correlations between company tax rates and wages and • Little or no correlation between personal tax and wages (against their AEI priors) Company tax and growth - empirical evidence Djankov, Shleifer et al, 2008, NBER Company tax over time Source: OECD, 2004 The case for ‘alignment’ – company v personal tax Practicality (anti-avoidance) suggests alignment But economic theory suggests taxing different kinds of income differently One can earn money in a company shielded from personal tax rate. But one can’t enjoy it! To spend money earned in a company owners and employees must be paid by company Triggering personal tax liability There is a tax deferral issue which, if it’s a problem should – and can - be handled with appropriate anti-avoidance provisions As it is elsewhere (and was here – till 1987) Alignment: Lifting thresholds versus cutting the top rate 16 The other miracle economy: The case of Ireland 30,000 48.00% 38.00% 20,000 28.00% 15,000 18.00% 10,000 8.00% 5,000 -2.00% 19 87 19 88 19 89 19 90 19 91 19 92 19 93 19 94 19 95 19 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 04 20 05 Annual per capita GDP ($US) 25,000 Annual per capita GDP growth (%) 58.00% Ireland GDP grow th Australia GDP grow th Ireland GDP per capita Australia GDP per capita The case of Ireland Ireland’s economic renaissance dates to 1987 when it aggressively courted foreign investment with tax cuts Its out-performance is commensurate with Lee and Gordon’s and Djankov, Shleifer’s results Ireland has a huge gap between top personal (42%) and company rate (12.5%) Dividend Imputation – We know its theoretical justification • To improve tax neutrality between debt and equity investment • To reduce double taxation of dividends – But is it cost effective as a capital taxation expenditure? – It now costs over $20 billion – How much does it lower the cost of capital? Ken Henry: 23 February 2009 An open economy model affects the way one should think about our company tax arrangements, including dividend imputation. 21 Dividend Imputation in economic theory Foreign investors are the marginal, more elastic investor So they disproportionately determine share prices. In fact Australian policy has • Extended domestic shareholders’ access to imputation credits – Superannuation – Refundability • Restricted pass-through of imputation to foreign shareholders. – So the marginal (foreign) investor purchases Australian shares with little regard to imputation. – So the value of credits is poorly represented in foreign demand for shares and so in share prices • which determine the cost of equity capital Dividend Imputation – the evidence Most reputable studies suggest that the value of imputation credits on the markets is 50 cents in the dollar or less. The most sophisticated econometric study by Cannavan, Finn and Gray (2004) suggests something close to zero valuation. Recent econometric evidence suggests that the introduction of dividend imputation did not increase share prices (Ickiewicz, 2006) Similar investigations of a tax credit scheme on dividends paid to UK pension funds yielded the same result. Credits under-valued and so were not reflected in share prices and did not lower the cost of capital. Removing these tax credits produced substantial reallocation of ownership, but with second order effects on price. (Bond, Devereux and Klemm; 2005) Dividend Imputation – Within firms credits are valued somewhere near zero. • Interview evidence suggests that in 80% of firms project analyses ignores value of credits earned. • Response of R&D to reductions in the tax concession strongly suggests that firms manage for profit after company tax, but before imputation credits. Recycling dividend imputation revenue as lower company tax – Accordingly we could ‘cash out’ an inefficient tax expenditure for an efficient company tax cut. – Allows cuts of up to 11 percentage points (Hathaway and Officer, 2004) – Company tax could go as low as 19% even without behavioral responses – Ireland cashed out its own dividend imputation system as lower company tax Recycling dividend imputation revenue as lower company tax • Likely effects – Abolition of DI => sale of Australian equities to foreigners. – Leads to only second order’ price effects (Bond, Devereaux and Klemm, 2005). – With lower company tax, FDI would rise substantially. – Improved post tax return on foreign investment in Australian shares rises lifting share prices • This lowers the cost of capital. • Increases investment Recycling dividend imputation revenue as lower company tax – “The coefficient estimates suggest that a cut in the corporate tax rate by 10 percentage points will raise the annual growth rate by one to two percentage points” (Lee and Gordon) – This would increase the payback above Mankiw and Weinzierl’s result – Or can be spent chasing lower company tax • Anti-avoidance and resource rent tax could also bring the rate lower, or generate higher revenue Recycling dividend imputation revenue as lower company tax Equity – This lowering of company tax is progressive – because it only favours foreign suppliers of capital – Downside is higher effective rate of tax on dividends to Australian shareholders • Share price rises provide compensation for those whose effective tax rate on dividends rises. Conclusion (i) Pierre Mendes-France “Gouverner, c'est choisir” – To govern is to choose The economist’s job is to say “this or that, not both. You can't do both”. Kenneth Arrow – Alignment and dividend imputation stem from worthy objectives • They also have opportunity costs • Those costs are greater than their benefits 29 Conclusion (ii) What’s there not to like?