Concept note:

The impact of short-term financial incentives on sexual behavior and HIV incidence

among youth: Evidence from a randomized controlled field trial in Lesotho

June 25 th, 2009

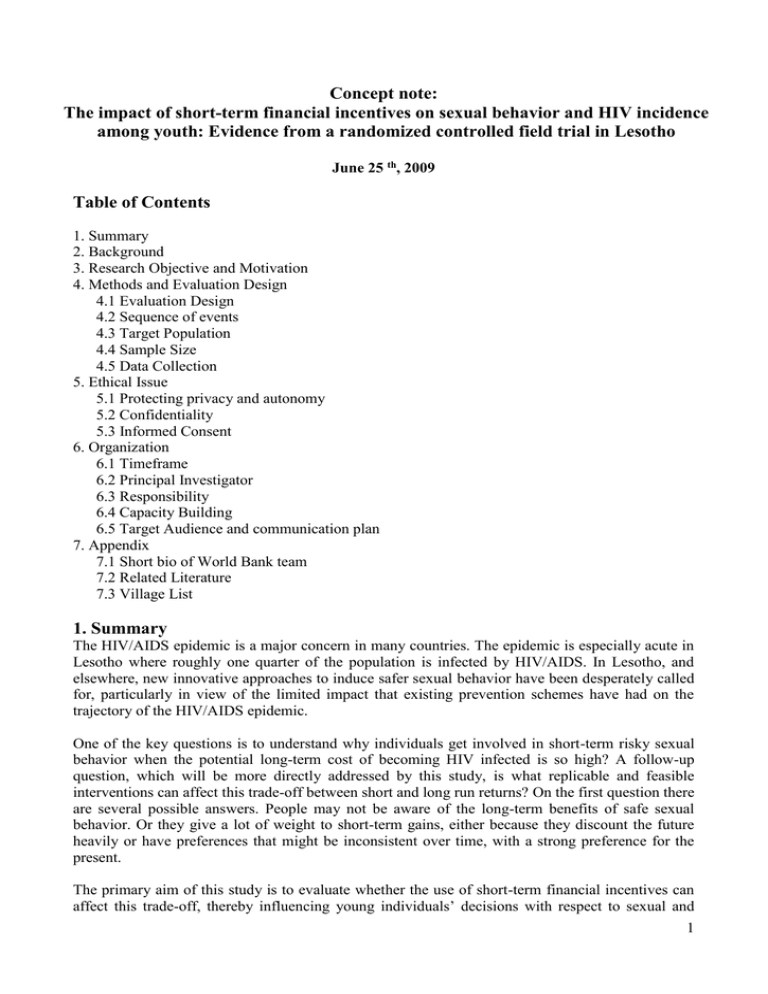

Table of Contents

1. Summary

2. Background

3. Research Objective and Motivation

4. Methods and Evaluation Design

4.1 Evaluation Design

4.2 Sequence of events

4.3 Target Population

4.4 Sample Size

4.5 Data Collection

5. Ethical Issue

5.1 Protecting privacy and autonomy

5.2 Confidentiality

5.3 Informed Consent

6. Organization

6.1 Timeframe

6.2 Principal Investigator

6.3 Responsibility

6.4 Capacity Building

6.5 Target Audience and communication plan

7. Appendix

7.1 Short bio of World Bank team

7.2 Related Literature

7.3 Village List

1. Summary

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is a major concern in many countries. The epidemic is especially acute in

Lesotho where roughly one quarter of the population is infected by HIV/AIDS. In Lesotho, and

elsewhere, new innovative approaches to induce safer sexual behavior have been desperately called

for, particularly in view of the limited impact that existing prevention schemes have had on the

trajectory of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

One of the key questions is to understand why individuals get involved in short-term risky sexual

behavior when the potential long-term cost of becoming HIV infected is so high? A follow-up

question, which will be more directly addressed by this study, is what replicable and feasible

interventions can affect this trade-off between short and long run returns? On the first question there

are several possible answers. People may not be aware of the long-term benefits of safe sexual

behavior. Or they give a lot of weight to short-term gains, either because they discount the future

heavily or have preferences that might be inconsistent over time, with a strong preference for the

present.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate whether the use of short-term financial incentives can

affect this trade-off, thereby influencing young individuals’ decisions with respect to sexual and

1

reproductive health behavior, and thus in the end reduce HIV incidence rates. We will study this

question using a sample of population attending New Start Voluntary Counseling and Testing

(VCT) sites that a local NGO, Population Service International (PSI), has already implemented in

Lesotho.

We propose to conduct a randomized controlled trial to test whether adding a financial incentive to

remain STI-negative in the form of a lottery can promote safer sexual activity. The lotteries will

work as follows: if the individual is tested negative on a set of curable STIs, she will get a lottery

ticket with the chance to win a “big” prize. If she is tested positive, she will receive free treatment,

but no lottery ticket. If an individual who tested positive is cured, she can come back in the lottery

system and get a later chance to win the lottery ticket if she remains STI-negative. The outcome will

be to measure the impact of financial incentives on HIV incidence after two years. Because lotteries

are inexpensive, we think we are testing a model that could be relatively easy to replicate.

As a second step, the project will also explore spillover effects. A higher number of STI and HIV

negative individuals within a community is a potential source of positive externalities for all

members who did not participate in the project. We might have externalities through two main

channels: first, the diffusion of information regarding HIV/STI prevention and second, a lower

probability to be involved in sexual relationships with positive partners.

Information about the cost of the information will also be collected so that we will be able to

measure the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and compare it with other HIV prevention

interventions.

The results of this research project will be disseminated through academic and non-academic

conferences, workshops, publications in academic journals, and also in policy journals with the aim

to reach out to policy makers outside the research community.

2. Background

Lesotho has the third-highest HIV prevalence in the world at 23.2% (DHS, 2004). Many HIV

prevention initiatives are currently going on in the country. The proposed impact evaluation

responds to the urgent need to find innovative approaches to promote safer sexual behaviors among

youths in Lesotho. In particular, the project will be implemented through the New Start Voluntary

Counseling and Testing (VCT) sites established by PSI in the country.

PSI, the implementing agency, has 5 static New Start VCT sites nationally in 5 out of the 10

districts in Lesotho. They are located in the main camp town of the following districts: Maseru,

Mafeteng, Qacha’s Nek, Maputsoe, Butha-Buthe. Each of these sites has vehicles and tents that are

used for outreach services. Outreach activities aim at targeting more specific groups of the

population who are generally at higher risk of HIV infection. For example, urban and semi-urban

villages (within 30 km radius from the static VCTs, working places (garment factories, phone

companies, etc.)) and schools. The present randomized evaluation aims at targeting youths in urban

and semi-urban villages (see section 4.3 for details).

PSI Lesotho has an extensive experience of working in the HIV prevention sector and it is currently

involved in various HIV prevention activities, including, in particular, condom distribution.

3. Research objective and Motivation

The result of traditional information campaigns (like ABC-Abstinence, Be Faithful and use

Condom) on sexual behavioral changes is not conclusive. Although, anecdotal evidence shows that

it has resulted in some changes, for example, interventions focusing on condoms use have resulted

2

in increasing condoms during commercial and sexual encounters, there is no rigorous evidence

actually showing a significant reduction in HIV prevalence in Southern Africa countries.1

Perhaps the reason for this resides in some differences in sexual behavior in Africa (e.g. it is much

more common to have concurrent partnerships that can overlap for significant time) and so the

information campaigns are not focusing on the right messages and thus not affecting behavior

where it matters the most. Or maybe, as recent literature suggests people tend to delay activities that

are a little bit unpleasant in the present (like protecting themselves) even if they have very large

returns in the future.2 People may not be aware of the long-term benefits of safe sexual behaviors.

Alternatively, they give a lot of weight to short-term gains, either because they discount the future

heavily or have preferences that might be inconsistent over time, with a strong preference for the

present.

What replicable and feasible interventions can affect this trade-off between short and long run

returns? Can the introduction of a small but "short term" reward promote safer sexual behaviors?

This intervention aims at contrasting the difference between a reward in the next 4 months (a lottery

ticket) and a reward 10 years later (being HIV negative). The main issue, is the interval between

the sexual activity and the lottery. To gauge the extent of participation in the lottery, the correct

interval time among lottery draws, and the impact on behavioural changes, we plan to do a short

qualitative study a couple of months before the beginning of the project.

The research objective is to test and rigorously evaluate whether the introduction of small financial

rewards in the short term can promote safer sexual behaviour in general, and reduce HIV incidence

in particular, in a high risk environment.

The results of the evaluation are expected to be an important input in designing effective HIV

prevention in Lesotho. Furthermore, a credible impact evaluation is also a global public good in the

sense that it can offer reliable guidance to international organizations, governments, donors, and

nongovernmental organizations in their ongoing search for effective HIV prevention programs.

4. Methods and Evaluation Design

4.1 Evaluation Design

We are proposing to conduct a randomized controlled field trial to rigorously test whether shortterm financial incentives in the form of lotteries have an impact on sexual behavior and the

incidence of HIV and a small set of curable STIs of youths coming in to outreach sessions of New

Start VCT in Lesotho.

The underlying question for the study is why individuals get involved in short-term risky sexual

behavior when the potential long-term cost of becoming HIV infected is so high, which clearly is

the case in Lesotho. It appears like individuals, to the extent that they have not been coerced into

having sex (which unfortunately is also a common problem); put a lot of weight on short-term gains

at the expense of long run benefits. If this is the case, short run financial incentives may affect

individual’s trade-off between short and long run returns. In fact, there exists some preliminary

evidence that small (financial) incentives associated with activities that have very high returns in the

1

An exception for this is Uganda that experienced a large drop in HIV prevalence in the 1990s, which is unique among

Sub-Saharan African countries; this drop is generally credited to educational programs, which promoted partner

reduction and to elements of ABC (Green, 2004; Green et al, 2006; Slutkin et al, 2006).

2

For example, Thornton (2008) studies the impact of monetary incentives to maintain HIV status on sexual behavior. In

particular, after testing for HIV, this study randomizes financial incentives to rural Malawians for successfully

maintaining status. Similarly Baird, Chirwa, McIntosh and Ozler (2009) assess the impact of a more traditional CCT

program, conditioned on school enrollment, on sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

3

future can result in significant change in behavior (Emont and Cunnings (1992), Kane (2004)

Krishnan-Sarin et al. (2000)). However, there is little (no) evidence that such an incentive scheme

will work when it comes to sexual behavior.

Thus, the main hypothesis to be tested is that a system of rapid feedback and positive reinforcement

using cash as an incentive can effectively lower risky sexual activity and reduce rates of HIV

transmission. The primary outcomes for evaluating impact will be a sub-set of sexually-transmitted

infections (STIs), Syphilis, Chlamydia, Gonorrhea,3 that are prevalent in the population and have

been incontrovertibly linked to risky sexual activity. Each of these STIs is curable. This is a critical

point, since enrollees who test positive for an STI can continue to participate in the study after they

have been treated and cured of the infection. Thus, learning is encouraged through positive

reinforcement, and mistakes can be corrected and overcome.

We will test study participants for HIV at baseline and after one year and two years to assess the

impact of the intervention on HIV transmission, but we will not condition participation to the

lotteries to HIV status.

We propose to test this hypothesis through the introduction of financial incentives in the form of a

lottery to remain/become STI-negative, which we believe is both replicable and relatively easy to

scale-up. Indeed, using a lottery system decreases the cost of the project compared with a

conditional cash transfer transferring a fixed sum of money to all individuals who remain STI

negative. Thus, the project might be easier to scale up with limited resources. Lotteries are also

more valued by risk-takers and these individuals might also be the ones with the most risky sexual

behavior, thus providing additional incentives would reach the most important group. The

presumption is that the financial incentive will influence individuals’ trade-off between short and

long run returns with respect to sexual behavior.4

The sample population will consist of youth aged 18-30 targeting through outreach activities in

urban and semi-urban villages implemented by the VCT centers in Lesotho We aim at a study

population of about 6,000 (see section 4.3 for details). To the extent demand will exceed supply; we

will randomly choose the participants.

In a clustered randomized controlled field trial the sample population is randomly divided into a

treatment group (individuals that will have a chance to participate in the lottery) and a comparison

(individuals that will not take part in the lottery) group. Here, the randomization will be at the

village level and therefore the analysis will cluster the standard errors at the village level Half of the

villages will be assigned to the treatment group and half to the control group. Since treatment has

been randomly assigned, and provided that the sample contains a sufficiently large number of

individuals, units assigned to the treatment and comparison groups are similar in expectations

before the intervention. The analysis will also control for observable characteristics. The causal

effect of the intervention can therefore be gauged by comparing mean outcomes in the treatment

and comparison groups after the intervention.

3

The study will remain open for testing other STIs, such as Trichonomasis and MGen, depending on budget, prevalence

and testing technology.

4

Raffles and other contests similar to lotteries are often advertised in the newspapers and on radio in Lesotho. It is

difficult to have detailed information on them (i.e. what are the chance to winning commercial lotteries or how many

people buy it), but the concept of lottery is common enough that most study participants will be familiar with it.

4

The random assignment to the control and treatment groups will be done in a transparent way, for

example by drawing from an urn which villages will be in the treatment and in the control group5.

Not only does randomization guarantee internal validity, it is also typically a fair way to allocate

participants across the treatment and the comparison groups.

Individuals both in the treated and in the control villages will receive free sexual health discussion

sessions as part of the PSI prevention and treatment program, free HIV/STI testing, free STI

treatment (for individuals tested positive), and free counseling before and after each STI/HIV test.

PSI also will provide free condoms in the VCTs.

Individuals in the treatment group villages will be eligible to participate in a lottery if they are

tested STI negative. There will be testing and lottery draw every four months. Participants will

know in advance the amount of the lottery reward. Suggestively, the amount of the reward will be

around 1000-2000 Rands and the lottery will be drawn among all the STI negative people in each

villages6. There will be 2 winners (i.e. one man and one woman) in each village. The exact details

on the type and the size of the reward will be more precisely decided during the pilot of the project.

The focus on STI status as a condition for participation in the lottery, rather than on HIV status, is

primarily based on ethical consideration. By focusing on STIs that are curable, we can also study

how the intervention affects behavior of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants. STIpositive individuals, who receive treatment and are cured, will be eligible to participate in future

lottery draws.

The proposal calls for two follow-up surveys, one after a 12-month period and one after a 24 month

period. We aim at surveying twice the sample of around 6,000 participants. To generate more

precise estimates of the impact of the intervention, a baseline survey will also be implemented. The

information from the baseline survey will also assist in stratifying the sample and will be used to

study heterogeneous effects. We are planning to study heterogeneous effects by gender and HIV

status and the power calculations have taken into account this stratification. In order to minimize

attrition during the project, we will collect data on names, addresses and phone numbers of the

participants in a way to preserve confidentiality and not to decrease their willingness to participate

(see section 5 for details). Further, we will provide small incentives (e.g. air time vouchers) for

participants to report to the study station

The design of this experiment avoids the usual complications of selection and reporting bias

because it randomized individual incentive to learn STIs status. However, there will be selfselection of people who choose to decide to participate in the study, because, for example, they are

more motivated and aware and perhaps knowledgeable about their options (in case they are HIV

positive) compared to someone who have tested. Those are mainly problems of external validity.

We are aware of these problems but in practice, they are difficult to avoid, since we cannot impose

this study on a representative sample of the population..

4.2 Sequence of events

The first thing would be to randomly allocate the villages between the control and treatment group.

We will randomly select villages from the list of villages with more that 150 youths from the list of

normal outreach activities of PSI. If the number of villages selected will not be enough to reach the

target sample size we will pick up additional villages from the Lesotho Census 2006. Individuals in

5

Because the randomization will be done in a transparent way, in public, it will not be possible to have the organization

administering the intervention blinded to the randomization.

6

We will study the possibility - once we have established in the first rounds that the lotteries are well accepted in the

study population - to randomly allocate different levels of prize over time and across village, moving away from a

simple binary treatment and providing richer variation in the level of treatment.

5

the target villages (both control and treatment) will be informed about the project through the

village chief.

Month 1

In each village, individuals in the target group, coming to the VCT outreach event, will be

registered and they will sign an informed consent. A survey will be conducted. We will collect data

on names, phone numbers, and addresses of the participants that will be kept in a separate file. We

will thus able to re-contact them during two years (see Section 5 for details). There will be the pre

and post test counselling, free sexual health discussion sessions as part of the PSI prevention

activities, free HIV/STI testing, free STI treatment (for individuals tested positive). PSI will also

provide free condoms. Each individual will receive a card with an ID number and they have to

present every time they will be tested. Informed consent will be required, so refusing HIV or STI

tests is a possibility. But we should only recruit individuals who, if they have provided informed

consent, are willing to take all tests.

We will provide an incentive, such as a grocery voucher to all the youths who agree on be part of

the project. Participants will be informed that PSI will come back after four months to test them

again and to provide them another grocery voucher for the value of about 25 Rands.

Month 5

Three or four days before the due date at month 5, a SMS firm will send to each participant a quick

reminder for their test. For those without cell phone, the reminder will be sent to the village chief.

Individuals in both the lottery and control villages will receive free sexual health discussion

sessions as part of the PSI prevention and treatment program, free STI testing, free STI treatment

(for individuals tested positive), and free counseling before and after each STI/ test. PSI will also

provide free condoms.7 Note that we will do HIV test only every year, at baseline, after 12 months

and after 24 months.

Individuals in the treatment group will be eligible to participate in a lottery if they are tested STI

negative. Every time clients will be tested, the enumerator will register the id number of that client

and provide her a Grocery voucher both in the treated and in the control villages.

After we target 150 youth per village, STI negative youth will be eligible to participate to a lottery

draws. A couple of participants will be called to do the lottery draw. The winner’s ID number will

be advertised in the village and we will ask to the winner to come and claim the prize. There will be

one lottery draw per village every four months.

Month 9, Month 16, Month 20

Same events as in month 5.

Month 12

Same events as in month 5 plus follow-up survey and HIV testing.

Month 24

Follow-up survey and HIV-testing

4.3 Target Population

HIV/AIDS is by far the leading cause of death for young people in sub-Saharan Africa (WDR

2007). While preventing new infections at any age is an important public health goal, achieving

7

We may decide to provide free STI testing in a subsample of the control villages in order to also test the effect of free

STI testing.

6

significant reductions in risky behavior among young people, aged 18-30, has the added attraction

of addressing a major concern about the impact of the AIDS epidemic on the demographic profile

of the most affected countries.

Adolescence and young adulthood corresponds to a period of identify formation, sexual identify

formation, and increased risk-seeking behaviors, but it is precisely this phase of life when

individuals are most receptive to changing norms, attitudes, and practices with regards to sexual

behavior. Thus, by offering the correct incentives during the critical transition to adulthood, it may

be possible to intervene before risky behaviors become firmly entrenched. The present project aims

at targeting youth aged 18-30 reached by New Start mobile VCT established by PSI.

There are 5 New Start VCT sites nationally, located in the main camp town of the districts Maseru,

Mafeteng, Qacha’s Nek, Maputsoe, Butha-Buthe. Each of these sites has vehicles and tents that are

used for outreach in their own catchment area. This project will focus on urban and semi urban

villages. In appendix, a list of the villages (from the Lesotho Census 2006) with an estimate of more

than 150 youth per village.

The project aims at targeting about 50 villages, of which half will be in the treatment group. We are

going to target about 12-13 villages per months in the all country and about 100-150 youths per

village. This would involve a total of 6,000-7,000 participants.

Table 1: Statistics on the target population:

No. of villages No. of villages in No. of villages in No

of No of youths tested and

in total

total per months

total per months youths per survey per villages per

per VCT

villages per day

(counting

20

month

working days per month)

50

12-13

2-3

150

7-8

Each VCT will have two outreach teams, composed by two nurses and two enumerators. To reach

our sample size, the two outreach teams will spend about 10-15 days in the first village and then

they will move together to the second and third villages for other 10-15 days. This means that each

nurse and each enumerator should roughly test and interview 7-8 youth per day. When they will

reach about 100-150 youth per villages they will move to the second village. 8 We also plan to target

villages during weekends to reach a higher number of youth.

PSI would like to expand the program to the whole population if funds will be provided by the

Lesotho Government or by other institutions. Furthermore, PSI will carry on their ordinary

activities in the static VCTs and in the villages out of the target villages.

4.4 Sample size

The protocol requires an 80% power of detecting a 50% reduction of annual incidence of HIV

infection in the core group of young individuals (18-30 years old) from 1% in the comparison group

to 0.5% in the treatment group. This gives us a sample of roughly 5,000 individuals in 50 villages.

The sample size calculations take into account the clustering within villages. As the invitation to

participate in the experiment, for both analytical and ethical reasons, will not be limited to only the

young HIV-negative individuals (HIV-positive individuals will also be allowed to participate), and

since we also want to be able to test if the sexual behavior of HIV-positive individuals can be

affected through financial incentive, the sample size was expanded to 7,000 individuals. This

8

From the data collected by previous Client Intake Forms at VCT level, this is seems reasonably.

7

sample size will ensure that we have enough core participants (HIV-negative individuals), while at

the same time it gives us enough power to detect a 50% reduction of annual incidence of sexually

transmitted infections (STIs) in the group of young HIV-positive individuals from 2.5% in the

comparison group to 1.25% in intervention group over two years.

Since expanding the sample size has obvious budget implications, an alternative evaluation strategy

has been developed that gives us less precision, or power, to detect a reduction of annual incidence

of STIs in the group of young HIV-positive individuals. This alternative strategy requires roughly

6,000 individuals in 50 villages.9

4.5 Data Collection and analysis.

In order to rigorously evaluate the impact of the program, we will conduct both a baseline survey of

participants prior to the start of the intervention and at least one post-survey (when the project has

been running for two years) of the participants. In addition to these two major surveys, the

participants in the treatment group will be tested for STI every quarter (since the lottery will be

based on the STI test result) and for HIV every year.

The survey and the data entry will be conducted by PSI. PSI will thus be responsible for the quality

of the data collection. The World Bank will provide funds to expand PSI capacity for the data

collection. Roughly, 10 enumerators are needed.

The research proposed will create new datasets. A survey among VCTs clients will be carried out

longitudinally, i.e. before the launch of the intervention (baseline) and after its launch (follow-up).

The survey of individuals/workers will contain general and more specific questions on health and

STIs/HIV.

Examples of modules to include in the surveys are:

1. Socio-demographic information

2. Life style risk factors (i.e. alcohol consumption)

3. Relationships and sexual behavior (i.e. age of sexual debut, condom use and other

preventative methods, age of partners, extra-marital relationships and concurrent partners,

sexual economic exchange)

4. HIV/AIDS and STIs knowledge

5. History of HIV testing and obtaining results (i.e. test before the survey, main reasons for

testing)

6. Perception of own risk of being HIV positive

7. Knowledge of people infected and who have been HIV tested

8. Violence and sexual abuse

9. Birth and Pregnancy history

10. Family situation (i.e. number of kids, how often do you see your partner, sources of income

for the family)

In both the baseline and in the follow-up surveys, we will test participants for STI and HIV. The

biological markers that have been selected for the study have been selected from a list of STIs that

are commonly used within the epidemiological literature as proxies for risky sexual behavior, and

that are known to be prevalent in the area where we will be working.

9

Details of the sample size calculations are available upon request from the lead investigators.

8

We have opted to include HIV testing, but we will not condition on it the participation to the lottery.

In any case, the study is sufficiently powered without including HIV as an outcome, and free HIV

testing is already available through VCT clinics in the area for anyone who wants it. We plan to

collect data on the following: Chlamydia; Gonorrhea; Syphilis through rapid tests.

To evaluate the program effect on the treated individuals, or the Average Treatment Effect (ATE),

we want to measure the difference between the potential outcome (Y1i) for individuals (Pi = 1) in a

treated village (Ti = 1) in the presence of the treatment and the potential outcome (Y0i) individuals in

a treated village in the absence of the treatment: ATE E(Y1i Ti 1, Pi 1) E(Y0i Ti 1, Pi 1) .

However, since we do not observe the potential outcome for individuals in a treated village in the

absence of the treatment, (Y0i), we use the individuals in control villages (Ti = 0) as the

counterfactual. We assume the potential outcome for individuals in a treated village in the absence

of the treatment in the village would be the same as the potential outcome for individuals in the

absence of the treatment in control villages, E (Y T 1, P 1) E (Y T 0, P 1) . Therefore, the ATE

0i i

i

0i i

i

is given by, ATE E(Y1i Ti 1, Pi 1) E(Y0i Ti 0, Pi 1)

.

The following equation is estimated to find the ATE for individuals:

Yi 0 1Ti 2 X i 3 Z i it

(1)

where Yi is an outcome for individual i (HIV or other STI status), Ti is the treatment indicator, Xi is

a vector of individuals characteristics (gender, age, education) and household characteristics

(wealth, parent education and literacy) and Zi is a vector of village level characteristics (village

infrastructure, school quality, village social capital)10. The direct impact of the treatment program

on the treated individuals, or ATE, is measured by 1.

5. Ethical Issues

No work on this study will begin prior to approval by all ethical oversight committees. Applications

will be submitted to a recognized academic ethical review acceptable to PSI and the World Bank

and if approved, to the Ethic Committee at the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Lesotho.

Notwithstanding these formal review procedures, the research team is aware of the ethical concerns

relevant to this research project. There is sensitivity around the idea that it may be possible to “buy”

and “reward” specific behaviors, and there is apparent concern that the proposed intervention

represents unwarranted interference in a matter of personal rather than public concern.

Our response to these concerns is several-fold. First, we believe that intervention can be justified on

the basis of market failures that are evident in health and may cause individuals to make privately,

and in particular, socially inferior decisions regarding sexual practices. This relates to the fact that

private markets do not facilitate optimal decision making by individuals for many reasons, and

these market failures may be magnified among youth and young people. Second, there is a sizeable

public cost in addition to the private costs associated with HIV infection. These costs have been

measured and assessed in many different ways and although the magnitude of the public burden

may be disputed, the fact of its existence is not. Third, it is important to emphasize that this is an

intervention of “carrots” (e.g. cash rewards through lottery; and free counseling and treatment) not

“sticks.” Individuals will be counseled prior to enrolment as to the nature of the study, and they

will have the option to decline to participate if they so desire. Finally, the individual’s privacy

regarding all aspects related to study participation, including STI testing, results, and treatment and

10

Alternatively, we will specify equations for the average treatment effect (ATE) that will use village fixed effects, i.e.

controlling for additive heterogeneity.

9

counseling, will be strictly protected according to criteria about informed consent and data use

established by the ethical oversight and review committees.

Thus, the study proposal rests solidly on the premise that risky sexual behavior is a) not in their own

best interest; and b) creates negative public health externalities on other members of society.

Moreover, the study will include all clients at the VCT sites in Lesotho. Although the primary target

is to study people, who have the highest incidence rates, we will not exclude any clients, both HIVpositive and HIV-negative individuals will be taken part of the field trial. Finally, individuals who

receive a positive STI result upon testing will receive free treatment and counseling.

5.1 Protecting privacy and autonomy

At all times, we will take several steps to preserve the subjects’ privacy and autonomy. All

individuals from the sample will be visited and informed of the objective and procedure of the

survey. We will inform the participants of their right to refuse participation in the study. In

addition, we will also assure the subjects that their choice regarding participation in the study will

not impact the care or service they currently receive or hope to receive from affiliated health

providers.

5.2 Confidentiality

We have developed various methods to safeguard against possible threats to confidentiality.

Participants will be informed that all information that they give us during the course of the study

will be strictly confidential, will be used only by the project investigators and will not be available

for other purposes. The results of the study may be published for scientific purposes, but will be

written in such a way that no individual can be identified.

To ensure further confidentiality, each subject will be assigned a unique identification number (ID),

and this code will be the only identification used on all study materials and laboratory specimen

logs. To be able to re-contact people over time, we will collect data on names and phone number of

clients, but the records linking the names and IDs will be kept locked in a secure storage facility.

After data are entered into a computer file, these computer records will be password protected to

limit access. The data files used for analyses will not include information that can be used to

identify individual households or individuals. The latter will be stored separately and will only be

used for re-surveying the study population.

At the follow-up surveys, we plan to re-interview the same individuals that were identified in the

first round. For use with follow-up surveys, only the module of individual roster will be kept in

paper format, which will include numerical identifiers. This part of the survey will be printed in a

different booklet from the remainder of the interview (“data”). The two booklets will be stapled

until the data have been entered. Once the data are entered, the identifying booklet will be separated

from the data booklet. The data booklets will then be destroyed. The identifier booklets will we kept

in a locked and secure place.

During the project we plan to do the STI test. To ensure confidentiality, each subject tested will be

assigned a unique identification number, and this code will be the only identification used. The HIV

testing will require that all information that might be used to identify individual survey respondents

be destroyed prior to the merging of the STI test results with the survey interview data. Therefore,

it will not possible to identify survey respondents.

5.3 Informed Consent

With regard to informed individual consent, we will follow the protocol established by similar

socio-economic surveys carried out in Lesotho. Consent will be obtained by asking to individuals if

10

they would be willing to participate in the survey. We will underline that they can refuse to

participate and that they can drop out from the project whenever they want. This is consistent with

procedures used previously and that constitutes a norm in Lesotho for evaluation surveys.

In addition to asking consent for the general survey, we will ask consent for STIs test. Subjects will

be explicitly asked for their consent before the test, by remembering them that it is a voluntary test.

The consent forms will be written in simple language at a sixth-grade reading level in local

language. The language used in the consent form will be developed in collaboration with PSI who

is familiarized with the procedures used to obtain informed consent for research studies. This was

done with cultural differences and local language patterns being considered. The staff will closely

review the consent form with all participants, and will read the following passage aloud to ensure

understanding. The consent statements are appended as separate documents.

For example, it would be like this:

Good morning/afternoon, Madam/Sir. My name is _____________ and I am here on behalf of the

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, to collect information your health.

This is a research project, and the findings may be used to design and plan appropriate policies to

fight against HIV/AIDS at a national level in the future. As a participant, you benefit by gaining a

better understanding of the advantages of prevention for HIV and AIDS. The study is expected to

last for around 2 years, so if you accept to cooperate you will probably receive further visits within

the next years.

Everything you tell me will be kept confidential. Under no circumstances will we link your name to

the data during the analysis and dissemination of the study findings. If you choose not to

participate, it will not affect you in anyway.

If you agree to participate, it will take about 30 minute to complete the interview. If you have any

further questions, during the study or in the future, please do not hesitate to contact the research

team using the telephone numbers below.

6. Organization

6.1 Timeframe

October 2008- April 2009: Preparation and design work

April 2009- April 2011: Fieldwork or material/information/data collection phase of study

July 2009-Pilot of the project

August 2009- August 2010: First analysis phase of study, including 4 waves of data collection on a

quarterly basis.

April 2010- September 2010: Writing-up of the research and Preparation of any new datasets for

archiving in STATA format. The data sets will be made available to interested researchers

following the time table and the guidelines of the World Bank Research Committee.

September 2010 – December 2010: Dissemination

6.2 Principal Investigators

The project will be implemented by PSI supported by the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare

(MoHSW) in Lesotho and the World Bank.

The World Bank team is composed of11:

Martina Bjorkman, IGIER, Bocconi University

11

A short biography of each World Bank team is reported in Appendix.

11

Lucia Corno, Institute of Interenational Studies (IIES), Stockholm University.

Damien de Walque, Economist, Development Research Group, The World Bank

Jakob Svensson, Institute of International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

The PSI team is composed of:

Michele Bradford, Country Representative, PSI/Lesotho

Mankhala Lerotholi, VCT Project Manager, PSI/Lesotho

Adam Smith, PSI, Program Officer, PSI/Lesotho

Mosele Machitje, MIS research Officer

New Start Site managers in the 5 VCTs

The MoHSW team is composed of:

Mrs M. Moteetee- Director General, MOHSW

Mr Katito Campbell - Operations Manager. Health Sector Reforms Programme, MOHSW

Mrs. M. Makhakhe – Director Health Planning, MOHSW

Mr.J. Nkonyana – Epidemiologist Heath Planning, MOHSW

Ms Senate Matete, Doctor, Ethic Committee, MOHSW

Mr. M. Khobotlo – Acting Chief Executive, NAC

6.3 Responsibility

PSI will be responsible for planning and implementing the intervention. The World Bank Team in

consultation with other partners will be responsible for the evaluation design, including randomly

sampling the clients included in the intervention, questionnaire design and data analysis. The two

parties will discuss and coordinate their plans and activities.

More specifically PSI will be responsible for:

- Organization of clients’ incentives (Grocery vouchers)

- Promotion activities on the project (Agreements with the village chiefs, posters)

- Localization of villages for outreaches with the higher number of individuals aged 18-30.

- Training of counselors on STIs

- Data collection and data entry

- Follow and re-contact individuals every four months for a two years window (through SMS).

More specifically The World Bank will be responsible for:

- Provide funds for the project

- Designing questionnaires for the baseline survey and the follow-up survey

- Analysing the data and writing a report on the results.

- Dissemination of the results

- Monitoring and supervising constantly the project with close interactions with PSI

6.4 Capacity building

This project will be conducted in collaboration with a local partner, Population Services

International (PSI). PSI, at global level, has already many platforms that run STI programs and has

extensive experience on how to run a STI program.

However, in Lesotho, while PSI has been involved in several HIV prevention activities and it is the

main provider of condoms in the country, they do not provide STI testing and treatment.

12

Participation in this study would help PSI Lesotho to open a new area of promoting safer sexual

behavior through STI prevention and treatment and to consolidate their capacity in all facets of HIV

research, from collection of biological specimens, to evaluation and assessment.

First, participants in both randomized and control groups will indeed receive free sexual health

discussion sessions by PSI workers, free HIV/STI testing, free STI treatment and free counseling

before and after each STI/HIV test. Since the project will be carry on a broad scale in the whole

country, this would increase the number of trained workers involved in the project in term of HIV

prevention. This would be a precious source with potential spillover to spread information on

HIV/AIDS in the whole country.

Second, even if PSI field workers have extensive experience in conducting visits and interviews,

they have had less experience with the evaluation of their work. They will be able to gain

experience in project evaluation. They will be involved in the random allocation of the villages and

in the lottery draw. They will be also trained for the data collection. It is very relevant for the

success of a project to understand what works and what does not, especially for targeting resources

toward projects that are really effective in HIV prevalence reduction.

Third, PSI members has been involved in designing and in writing the present proposal, thus,

through the involvement in this project, they will be able to run other randomized experiment in the

future by their own. It is very relevant for the success of a project to understand what works and

what does not, especially for targeting resources toward projects that are really effective in HIV

prevalence reduction.

6.5 Target Audience and Communication Plan

The primary target audience for this project includes the Government of Lesotho (the National

AIDS Commission, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW)) and policymakers

working on HIV/AIDS prevention in Lesotho. However, as we are studying a simple intervention

that is both relatively easy to scale-up and replicate, the results should be of general interest to both

government, non-government, and the donor community in their effort to identify efficient ways to

fight HIV/AIDS.

The results of this research project will be disseminated through academic and non-academic

conferences, workshops, publication in academic journals, and also in policy journals with the aim

to reach out to policy makers outside the research community.

7. Appendix

7.1 Short Biography of The World Bank Team

The World Bank team is composed of:

Martina Bjorkman, IGIER, Bocconi University

Martina Björkman obtained her PhD in Economics from the Institute for International Economic

Studies at Stockholm University in 2006. She is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Bocconi

University in Milan. She is currently Research Affiliate of the Centre for Economic Policy Research

(CEPR), the Innocenzo Gasparini Institute for Economic Research (IGIER) and the Fondazione

Rodolfo Debenedetti (fRDB). Her fields of interests are development economics, economics of

education and health, economics of gender and political economics. Martina Björkman is currently

working on research projects in Uganda, Lesotho and South Africa. Most of her field-based

research relates to randomized experiments within the health and education sector. At Bocconi

University she teaches undergraduate macro economics and undergraduate and graduate courses in

development economics.

13

Lucia Corno, Institute of Interenational Studies (IIES), Stockholm University.

Lucia Corno is a Post-Doctoral research fellow at Stockholm University. She is close to obtain her

Ph.D. in Economics at Bocconi University in Milan, Italy. Her fields of interests are mainly

development economics and health economics. She has been involved in research studies on the

health seeking behavior in Tanzania, the determinants of HIV/AIDS in Lesotho (using of

Demographic Health Survey 2004). Her most recent research includes the relationship between

homelessness and crime.

Damien de Walque, Economist, Development Research Group, The World Bank

Damien de Walque is an Economist in the Development Research Group (Human Development and

Public Services Team) at the World Bank. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from the University

of Chicago in 2003. His research interests include health and education and the interactions between

them. He has been involved in a study on the relationship between schooling and HIV infection in

Uganda, as well as analyzing the effect of education on other health outcomes, like smoking

behaviors. He is working on evaluating the impact of HIV/AIDS interventions and policies in

several African countries. He also developed a research agenda focusing on the analysis of the longterm consequences of mortality crises. He has participated in several World Bank missions in

Lesotho and has survey work experience in many African countries.

Jakob Svensson, Institute of International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

Jakob Svensson is a Professor of Economics, Institute for International Economic Studies (IIES),

Stockholm University. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from Stockholm University in 1996 and

spent five years at the Research Department of the World Bank before joining IIES. His research

interests include, among others, health and education. He has been the project leader of several

large surveys in the education and health sectors, and he recently (jointly with Martina Björkman)

managed a large prospective (randomized) evaluation of an accountability intervention in the health

sector in Uganda.

7.2 Backgroud literature

Askew, I and Berer, M (2003). “The contribution of sexual and reproductive health services to the

fight against HIV/AIDS: a review.” Reproductive Health Matters 11(22):51-73.

Bertrand, JR and others (2006). “Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication

programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries.” Health Education and

Research 21(4):567-97.

Baird, Chirwa, McIntosh and Ozler (2009) “The Impact of a Conditional Cash Transfer Program for

Schooling on the Sexual Behavior of Young Women in Malawi”, working paper

De Janvry, A. and E. Sadoulet. 2004. “Conditional Cash Transfer Programs: Are They Really

Magic Bullets?” Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics: University of California,

Berkeley.

Donatelle, Rebecca and others. 2000. “Randomised controlled trial using social support and

financial incentives for high risk pregnant smokers: Significant other Supporter (SOS) program.

Tobacco Control 9: 67-69.

Emont, S. and K Cummings. 1992. “Using a low-cost, prize-drawing incentive to improve

recruitment rate at a work-site smoking cessation clinic.” Journal of Occupational Medicine

34:771-4.

14

Farrington, John and Rachel Slater. 2006. “Introduction: Cash Transfers: Panacea for Poverty

Reduction or Money Down the Drain?” Development Policy Review 24(5):499-511.

Fiszbein Ariel and Norbert Schady (2008). “Conditional Cash Transfers for Attacking Present and

Future Poverty”, Policy Research Report, forthcoming, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Gertler, Paul (2004). “Do Conditional Cash Transfers Improve Child Health? Evidence from

PROGRESA’s Control Randomized Experiment” The American Economic Review 94(2): 332-341.

Haug, Nancy and James Sorensen. 2006. “Contingency management interventions for HIV-related

behaviors. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 3(4).

Higgins and others. 1994. “Incentives improve outcomes in outpatient behavioral treatment of

cocaine dependence.” Archives of General Psychiatry 51: 568-76.

Jeffrey, RW and others. 1984. “Effectiveness of monetary contracts with two repayment schedules

of weight reduction in men and women from self-referred and population samples.” Behavioral

Therapy 15:273-9.

Jeffrey RW and others. 1978. “Effects on weight reduction of strong monetary contracts for calorie

restriction or weight loss.” Behavioral Res Therapy 16:363-9.

Kamb, ML and others. 1998. “What about money? Effect of small monetary incentives on

enrollment, retention, and motivation to change behavior in an HIV/STD prevention counseling

intervention. The Project RESPECT Study Group.” Sexually Transmitted Infections 74:253-55.

Kane, Robert, and others. 2004. “A Structured Review of the Effect of Economic Incentives on

Consumers’ Preventive Behavior.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 27(4):327-52.

Krishnan-Sarin, S. and others. (2006). Contingency management for smoking cessation in

adolescent smokers.” Experimental Clinica Psychopharmacology 14(3):306-10.

Mauldon, Jane Gilbert. 2003. “Providing Subsidies and Incentives for Norplant, Sterilization and

Other Contraception: Allowing Economic Theory to Inform Ethical Analysis.” Journal of Law,

Medicine, and Ethics 31:351-64.

Nigenda, Gustavo and Luz Maria Gonzalez-Robledo. 2005. “Lessons offered by Latin American

cash transfer programmes, Mexico’s Oportunidades and Nicaragua’s SPN: Implications for African

Countries. DFID Health Systems Resource Centre.

O’Donoghue, T. and M. Rabin. 2001. “Risky Behavior Among Youths: Some Issues from

Behavioral Economics” in Risky Behavior Among Youths, J. Gruber, ed. Chicago, University of

Chicago Press: 29-68.

Paul-Ebhohimhen, V. and A. Avenell. 2007. “Systematic review of the use of financial incentive

in treatments for obesity and overweight.” Obesity Reviews 1-13.

Philipson, T. and R.A.Posner (1995). “The Microeconomics of the AIDS Epidemic in Africa.”

Population and Development Review 21(4):835-848.

15

Rawlings, Laura and Gloria Rubio. 2005. “Evaluating the Impact of Conditional Cash Transfer

Programs.” The World Bank Research Observer 20(1): 29-55.

Rawson, R. (2002). “A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral

approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence.” Archives of

General Psychiatry 59(9):817-24.

Rosen, M and others. (2007) “Improved Adherence with Contingency Management.” AIDS

Patient Care STDS 21(1):30-40.

Schady Norbert, and José Rosero. (2007). “Are Cash Transfers Made to Women Spent Like Other

Sources of Income?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4282, The World Bank,

Washington, DC.

Schubert, Bernd and Rachel Slater. 2006. “Social Cash Transfers in Low Income African

Countries: Conditional or Unconditional?” Development Policy Review 24:5.

Schuring, Esther. 2005. “Conditional Cash Transfers: A New Perspective for Madagascar?” A

World Bank Report (unpublished).

Silverman, K. and others. 1996. “Sustained cocaine abstinence in methodone-maintenance patients

through voucher-based reinforcement therapy.” Archives of General Psychiatry 53:409-15.

Sindelar, J. and others. 2007. “What Do We Get for Our Money? Cost Effectiveness of Adding

Contingency Management.” Addiction 102(2):309-16.

Stizer, Maxine and Nancy Petry. 2006. “Contingency management for treatment of substance

abuse.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2:411-34.

Thornton, Rebecca (2006). “The Demand for and Impact of HIV Testing: Evidence from a Field

Experiment”. Processed.

UNAIDS (2001). Global Crisis-Global Action: Preventing HIV/AIDS Among Young People.

Geneva, UNAIDS.

UNAIDS (2007). Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva, UNAIDS.

Weedon, Donald and others. 1986. “An Incentives Program to Increase Contraceptive Prevalence

in Rural Thailand.” International Family Planning Perspectives 12(1):11-16.

Windsor, RA, Lowe JB, Bartlett EE. “The effectiveness of a worksite self-help smoking cessation

program: a randomized trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 11:407-21.

Yeh, E (2006). “Commercial Sex Work as a Response to risk in Kenya.” University of California,

Berkeley Disseration in the Department of Economics.

7.3 Background data from the Lesotho Census 200612

Village list with a number of people aged 18-30 higher than 150 in each district

12

Data from the census 2206. We impute 40 percent of the population as aged 18-30 (from the DHS is the 46% but on a

sample of 15-59).

16

Berea

Ha Boose

Ha Buasono

Ha Lebina

Ha Lehlohonolo

Ha Lenkoane

Ha Letsoela

Ha Maritintsi

Ha Mohlaetoa

Ha Mokhameleli (Ha Tjotji)

Ha Moroke

Ha Nkhahle

Ha Patso

Ha Sakoane

Ha Ts'ekelo

Koalabata

Malimong (Ha Mapeshoane)

Maphiring

Mapolateng

Maqhaka

Marabeng

Naleli (Ha Ts'osane)

Sebalabala

Tsipa

Tsokung

Butha Buthe

Ha Mofolo

Ha Kuini (Lithakong)

Liqalaneng

Marakabei

Phahlane

Tebe-tebe

Tlapeng

Leribe

Ha Mathata

Ha Khomoatsana

Ha Lejone

Ha Mahloane

Ha Majara

Ha Maqele

Ha Mathata

Ha Matube

Ha Matumo

Ha Mohlokaqala

Ha Mokati

Ha Molelle

Ha Mositi

Ha Nena

Ha Polaki

Ha Polile

Ha Sekhonyana

17

Ha Simone

Ha Thokoa

Hleoheng

Khanyane

Lekhalong (Ha Mafata)

Lekhalong (Ha Qamo)

Levis Nek

Lisemeng

Lisemeng II

Mamohau

Maqasane

Matukeng

Mokoallong

Naleli

Pitseng (London)

Pote

Qophelo

Soweto

Tabola 1

Tiping 1

Ts'ifalimali

Tsoekereng

Vukazenzela

Mafeteng

Ha Kabai

Ha Konote

Ha Mabatla

Ha Mafa

Ha Mofoka

Ha Ngoale

Ha Petlane

Ha Ramarothele

Ha Sehlabo

Ha Sekhaupane

Haseng

LeCoop

Makeneng

Makhomalong

Maralleng

Mathebe

Methinyeng

Mohlanapeng

Motsekuoa

Tibeleng

Maseru

Bochabela I

Bochabela II 1

Boquate (Ha Majara)

Borokhoaneng2

Fika-le-Mohala (Orlando)

Ha Abia

18

Ha Jimisi

Ha Khoabane

Ha Leqele

Ha Lesia

Ha Leteketa

Ha Mabote

Ha Mabote (Motlakaseng)

Ha Mabote (Nokeng)

Ha Mabote (Thoteng)

Ha Mafefooane

Ha Maja

Ha Makhalanyane

Ha Makhoathi

Ha Malelo

Ha Mantsebo

Ha Matala

Ha Mohasoa

Ha Motemekoane

Ha Motloheloa

Ha Mpo

Ha Paanya

Ha Pita

Ha Ramabele

Ha Ramatekane

Ha Ramokitimi

Ha Ramorakane

Ha Rasetimela

Ha Sekepe

Ha Seleso

Ha Seoli

Ha Shelile

Ha Sofonea

Ha Teko

Ha Thetsane

Ha Tikoe

Ha Tjameli

Ha Tlali

Hata-Butle

Khubetsoana (Ha Nkhala)

Khubetsoana (Nts'irele)

Lekhaloaneng

Leralleng

Letlapeng

Lithabaneng (Ha Keiso)

Lithabaneng (Ha Matala)

Lithoteng (Ha Seleso)

Lower Thamae

Machekoaneng

Mafikaneng

Mafikeng

Mafikeng (Ha Motoko)

19

Mahlabatheng

Mamenoaneng

Maqalika

Maqalika (Litupung)

Maseru Correctional Service

Maseru East

Maseru West

Maseru west

Matukeng

Mohalalitoe

Moshoeshoe II

Motimposo

Naleli

Naleli (Khutsong)

Old Europa

Phahameng

Qoaling (Ha Letlatsa)

Qoatsaneng (Ha Tsautse)

Ratjomose

Seapoint

Selakhapane

Semphetenyane

Thabong

Thetsane West

Thibella

Thoteng

Ts'enola (Majoe-Lits'oene)

Upper Thamae

Total 112

Mohale

Ha Matabane

Ha Moletsane

Ha Phafoli

Ha Potsane

Ha Rakoloi

Ha Sehaula

Quacha

Ha Makoae

Ha Mapote

Ha Matlali

Ha Mosiuoa

Ha Seteleng

Keiting

Leseling

Makhalong

Mosafeleng

Motse-Mocha

TJ

Quithing

None

Thaba

20

Ha Khoanyane

Ha Laka

Ha Motsepa

Ha Rats'iu

Ha Toka

Lebung

Liqonong

Mohlakeng

Ponts'eng

Thabong

th

Maseru, 9 April, 2009

Principal Secretary, MOHSW

--------------------------------

Ms Michele Bradford

PSI Country Representative

------------------------------------

Ruth Kagia

Country Director for Southern African Countries, The World Bank

----------------------------------

21