Free care findings in Sudan

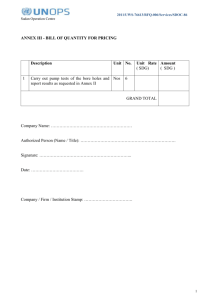

advertisement

Free healthcare policy for under-fives and pregnant women in northern Sudan: findings of a review Dr Sophie Witter on behalf of FMoH team March 2011 Research team Key informant interviews Khalda Khalid Rania Hussein Sally Hassan Gassim Elsadig Eltigani Fatima Elzahra Ismail Costing team: Mohammed Saed Fatima Abderhamn Mohamed Yahia Ahmed Khalil Khadiga Mohamed Bader Facility survey/exit interviews Hiba Nasser Eldain Asrar Faddul Elsied Afraa Hamid Isra Abdemagid Dr Manarr Abdelrahman, University of Khartoum Background to policy Free health care until 1992, then cost-sharing introduced NHI starts in 1995 Free emergency care, 1996 Interim Constitution, 2007 – rights to basic health care 2007 National Health Policy with focus on MDGs and vulnerable groups Free care for pregnant women and underfives announced by President, January 2008 Some background on health indicators Selected health indicators, 2007, Sudan IMR 99/1,000 MMR 595/100,000 Facility delivery rate CS rate 22% 5.60% Overall poor Some improvements but others stagnating (e.g. MMR) Substantial inequities (regional and by quintile) e.g. CS: range from 0.8% in West Darfur to 14.2% in River Nile & from 1% in Q1 to 19% in Q5 Study objectives To understand and advise on: The content and cost of the package of care The flow of funds from federal to states level How the policy is managed and monitored The impact of the policy How the free care policy is linked to drug supply systems and to other health programmes (including other free care programmes and HI) In addition, it sought stakeholder views on the policy, its implementation, on problems which it faces, and on proposed solutions to those problems. Conducted by FMoH, funded in part by MDTF Research tools 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. key informant interviews (214) exit interviews (138 women; 248 <5s) facility survey (30) costing of package (24) secondary data and literature Focal states: Khartoum, Red Sea, Kassala, Blue Nile, South Kordofan Study period: Jan-September 2010 Study limitations For KII, getting written reports was main challenge For facility survey, no major constraints For exit interviews, gaining adequate sample (especially for deliveries); plus some difficult questions on expenditure For costing, gaps in financial records Ended up having to exclude financial analysis for two states Secondary data very fragmented and sometimes with gaps (e.g. HMIS) Summary of findings Policy specification Not clearly specified – no detailed written guidelines Very varied implementation By kind of facilities included By services included By type of costs covered (or how much covered) Rationing has favoured hospitals, inpatients & urban areas (e.g. RS: only 6% to HCs) Compounded by inadequate funds and drugs Overall expenditure Federal funding – little addition by states or localities, except in Khartoum In 2009, 0.58 SDG ($0.28) per person for northern states as a whole 13% of free care spending; 6% of free drugs* 1% of expenditure on health at state level (RS + BN) 0.005% of total public expenditure (NHA figures) *less than a quarter of amount to renal centre Were resources adequate? All KI agree on inadequacy, though estimates of gap vary (60-100%) Hard to estimate as no unit costs established before (for budget setting) and reporting too aggregated Using our cost estimates, the funding for 2009 would only have covered 7% of needs (assuming package = all CS and all child care) Flow of resources Budget-setting not well understood Resources erratic (especially cash) Drugs more reliable but still limited in quantity and type Within states, varying approaches to distribution – percentages, fixed amounts, according to judgement of need etc. Partially suspended or stopped in a variety of ways in each state Impact on utilisation 2008-9: 45% increase in child care cases; 14% normal deliveries (free care report); 24% CS Consistent with international experiences (also facility survey and exit interviews) Big increases in ultrasound (for deliveries) and operations (for children) HMIS data (?quality) shows steady rise over past few years of CS by c.25% per year But concern that two-thirds of CS elective in northern Sudan Impact on households Exit interviews show households still paying for most items mean of 62 SDG per child care episode and 248 SDG per delivery Costs unpredictable: range for CS of 54 SDG to 1,054 SDG Costs higher when add drugs to be purchased outside (61% of drugs prescribed to women not in stock, for example) <2% totally free (both groups) 39% of households (children) and 50% (women) paid for drugs, even though they were in stock Of household monthly spending after food, one child episode costs 44.5% and delivery 213% on average 53% cannot afford to pay (children); 66% (women) Health insurance and payments 29% covered in children’s exit interviews; 24% in women’s For both groups, those with insurance paid more (though difference not significant) More likely to say they can afford care, but still the minority (34% of insured carers of children could afford and 42% of women) Impact on quality of care Mixed qualitative reports – concerns but no evidence of deterioration No evidence of increase in stillbirths 51% of children >2 visits before – why? Gradient of infrastructure and staffing between Khartoum and other states Basic equipment lacking (and sometimes worse at higher level facilities) For women, quality is no. 1 consideration (for children, proximity) High user satisfaction except on price and drugs Impact on facilities Between 6% (SK) and 81% (RS) of facilities participating in policy Context of varied rules on use of user fees Reports of increased workload (for some, not all) Reports of debts (for some; others just charge) Balance of revenues and expenditures over 2007-9 show improvements for most, which suggests they are coping For staff, loss of incentives from fees (but gains from drug sales?) Findings on drugs supply system Drugs absorb over half of free care funds (and single biggest item of expenditure for patients too) Supply not functioning well though: Free care adds to multiple channels CMS + RDFs not able to reliably stock essential items (often have to buy from private sources) Facilities have to transport free care drugs Availability at facilities poor (e.g. 61% out of stock, according to women’s EI) This was also found by facility survey – lack of even basic items, like gloves Also higher prices at peripheral units – regressive Linkages with health insurance Free care used as ‘first line’ in most cases – subsidises NHI – this is also patients’ preference as avoid co-payments But given the insufficiency of resources, NHI still bears costs, in theory However, in practice, cash-flow issues and blocked payment channels in many areas Plus free care is potentially disincentivising for NHI At present, patients are still paying either way! Monitoring of policy Monitoring weak – no budgets for supervision, no checklists etc. Not combining with other programmes with resources (e.g. Global Fund) Reports varied in format, hard to analyse Very fragmented information sources; not combined to analyse outputs, unit costs, trends, how funds used etc Overall views of key informants In short: Good policy but poorly done Many practical suggestions for how to strengthen RECOMMENDATIONS Is the policy needed? Yes Constitutional right Important to fulfil most of the objectives of the 2007 health strategy Focuses on vulnerable groups Poor health indicators and huge inequalities (10% inst deliv Q1 vs 55% Q5, 2006 SHHS) Households bearing the brunt of costs - 67% of total from them, according to NHA, and of this, 97% is out-of-pocket If so, how to implement it? Option A – to continue the free care as currently designed, but with improvements to funding, clearer guidelines and stronger monitoring and evaluation Option B – to continue the policy as at present, but switching to a more explicit output-based system, with funds following activities Option C – to use the health insurance system as a way of creating entitlement for free (or largely free) services for the target groups Option D – to change the focus to providing integrated free funding at all primary facilities Option E – other possible approaches, such as establishment of health equity funds, use of vouchers and conditional cash transfers. Package of care Current situation: overlapping free care policies and value-added of services unclear Need for integration of policies to cover normal deliveries (gateway to care); emergency CS and other complications; all main children’s conditions, whether IP or OPD Ideally for mothers, full package of ANC, delivery care, and PNC, including FP Available at close-to-user facilities (first and second line) The cost Choice of approach is needed before detailed costing can be done But the study generated broad-brush budgets for each scenario to inform debate For A or B, cost for all deliveries and <5s care would be about 19% of the total public expenditure on health For C, needs more detailed elaboration with NHIC For D, all care at rural hospitals and health centres would cost in range of 10% of total public health expenditure How to fund these? Develop clearly specified, costed package with credible implementation mechanisms Accompanied by reforms to improve effectiveness of sector These will include reallocating funds away from some high-cost tertiary centres Current spend per capita is $122 ($34 from public sources) so can afford to fund essential care, but health indicators poor and inequitable Once improved use, then have the basis for arguing for additional pooled resources (Abuja targets (currently 6.6% of public expenditure on health, reduction in OOP etc.) Monitoring and evaluation Whatever option is chosen, stronger M&E is needed – we elaborate framework to include indicators on: Coverage Cost Equity indicators Sustainability Financial protection Rational, high priority care Quality of care Accompanying reforms which are needed….some examples To strengthen: Drug supply system Clinical practice Primary care Strengthening NHI More transparent & fair resource allocation Drug supply system Study found evidence of too many parallel systems, poor availability, and high prices Accelerate integration of 15+ national programmes and CMS/RDFs CMS re-focussed on core role of not-for-profit supplier of essential drugs to all parts of Sudan Operate national pricing and transport to all public facilities In return, all debts to CMS paid off – no longer creditor of last resort Clinical practice Great variation across facilities in drugs and tests – often not in accordance with standards Need for provider-friendly protocols and training Payment mechanisms to be linked with meeting standards Upgrading of equipment necessary too Revitalising primary care Need to correct bias towards hospitals (both by the system and patients) by: freeing care/reducing financial barriers at the primary level developing resource allocation mechanisms which ensure more predictable funding integrated planning for infrastructure improving the drug supply to peripheral facilities motivating staff who stay in rural areas installing gate-keepers (through regulation or prices) NHIC - recommendations Development of actuarial analysis by the NHIC Reform of the payment mechanisms (currently FFS) Clear national guidelines on the payment channels for state-level NHI reimbursement of services Investigating factors behind cash flow problems (including regularity of contributions from MoF) What we have learned (internationally) Confirms findings from other countries that exemptions policies targeted at vulnerable groups are often poorly specified, funded, implemented and monitored In Sudan, the story is complicated by the federal system, the NHI, the drug supply (revolving drugs) system, the multiplicity of free care and vertical programmes, and the mixed practice on financial autonomy of public facilities Confirms that exemptions appear simple, but are complex, as involve addressing systemic issues Should be combined with – and may help to trigger? wider set of health sector reforms Shukran!