Background Narrative

advertisement

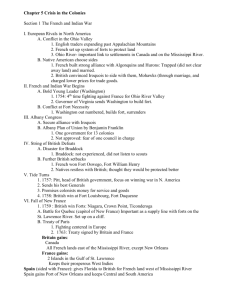

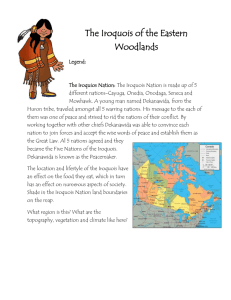

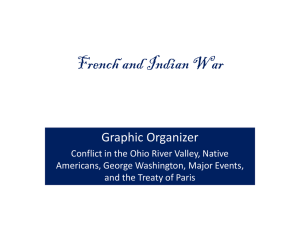

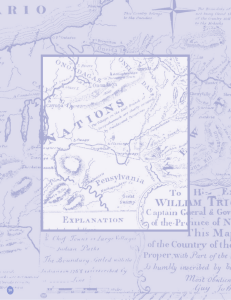

Background Narrative England and France fought three wars against each other – King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, and King George’s War, primarily in Europe during the 1600s and 1700s. As a result, the colonists played relatively minor roles. However, following the third, the French began to build forts in the rich lands of the Ohio Valley that they considered a vital link between New France (Canada) and Louisiana. Also, they wanted to protect their fur trapping and trading. At the same time, George II was granting huge tracts of land in the Ohio Valley to citizens in Virginia who saw the economic and financial potential of the area. The French, alarmed by this development, prepared to defend what they considered French territory. More forts were added along the Great Lakes. In 1752, the Marquis Duquesne was made governor-general of New France with instructions to remove the British from the Ohio Valley. In 1753, he sent troops to build Fort Presque Isle near Lake Erie and Fort LeBoeuf in the part of the Ohio Valley claimed by Virginia. When Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, learned the French had built more forts, he sent out a small party under the command of a young George Washington to deliver a letter of protest to French officials, demanding that they leave the region. The mission was a failure, because the French summarily refused to vacate the area. However, as he passed through the region, Washington noticed a strategically-located site where the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers meet to form the Ohio River – one that would be an excellent spot for a fort. The British began to build a fort at what is now present-day Pittsburgh. They were interrupted by a larger French force that chased off the British and completed the fort, naming it after the Marquis Duquesne. In 1754, Governor Dinwiddie sought but failed to get help from the other colonies, because he felt that this was a threat to the safety of the colonists and a barrier to westward expansion. To counter this threat, he sent a second expedition to attack the fort, again under the command of George Washington. On May 28, they advanced on the fort, ambushed a French scouting party, and took a number of captives. The colonial forces constructed Fort Necessity, a small and simple structure. On July 3, the French forces retaliated by capturing Washington’s entire force, but later released them. The French and Indian War had begun, even though there had been no formal declaration. In North America the French and Indian War changed the future of the continent and impacted many cultures: English, American, French, Canadian, Huron, Algonquian, Iroquois, etc. Each side, French and British, found allies in Native Americans. The French usually got along with Native Americans because they did not threaten the Native American way of life. In fact, French traders had lived among the Indians for years and had married into their culture. They learned to respect native traditions and did not destroy the land where Native Americans hunted – because fur trade, not farming, was New France’s main source of income. Many Algonquian-speaking nations allied themselves with the French, including the Miami, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Ojibwa, Menominee, Huron, Shawnee, pro-French Seneca, and Delaware allies at Monongahela River. The British allied themselves with the Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee (hou-DE-nohsah-nee). The Iroquois nations: Seneca, Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, and later the Tuscarora, had formed a strong alliance in which each nation pledged to protect the others. This alliance made the Iroquois very powerful. It protected them from outside enemies but ensured them of internal peace. Once a year, each nation sent representatives to a council, where concerns were addressed and voted upon. The League’s constitution was written in symbols of unity on a beaded wampum belt. The nations inhabited western New York, which included all the major trade routes of the region and stretched from Niagara Falls to Albany, New York, from New England to Ohio. The Iroquois had been enemies of the French since Samuel de Champlain sided against them by joining forces with the Huron in battles against them in 1609. In 1754, the British government asked the Iroquois to side with them. At first, the Iroquois refused. They pointed out that the British and French were fighting over Iroquois land, but when the French and British began to fight in their forests, the Iroquois were pulled in. The British were able to get the aid of the Iroquois with the help of William Johnson, an English fur trader, who settled in the Mohawk Valley. The Mohawk called him Warraghiyagey (warrag-ee-YAH-gay), which means “Doer of Great Things.” He was married twice to Mohawk women; one was Mary, also called Mary Brant, sister of Joseph Brant. Through his marriages, Johnson became so influential that he was made a British baronet and commissioned “Colonel of the Six Nations.” Johnson called a meeting of the Iroquois Confederacy, where he promised the nations that their land would be protected. He tried very hard to honor that promise, but others did not. Works Cited Chorlian, Meg. “Contest for Empire, 1754-1763.” Cobblestone (Sept., 2005), 4-11. Collier, Christopher, and James Lincoln Collier. The French and Indian War 1660-1763. New York: Benchmark Books, 1998. Gard, Carolyn. The French and Indian War: A Primary Source History of the Fight for Territory in North America. New York: Rosen Publishing, Inc., 2004. Maestro, Betsy. Struggle for Continent. Singapore: Harper Collins Publishers, 2000. Yoder, Carolyn. “French and Indian War 1754-1763.” Cobblestone (Aug.-Sept., 1991), 1-10.