Judicial Review in Admin. Law

advertisement

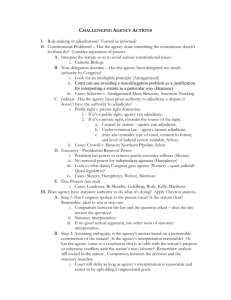

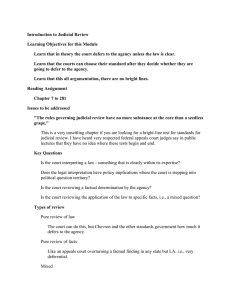

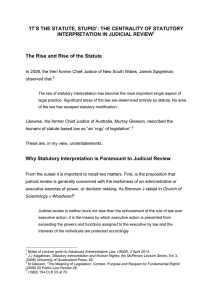

Judicial Review in Admin. Law General Assumptions The admin state rests on presumption that benevolent experts know how to make “wise” policy Therefore, judges should defer to agencies and refrain from second guessing them Does this philosophy weaken or strengthen admin law? Does it favor judicial activism or restraint in admin law? There are some problems with these views “Capture” Inconsistent philosophies w/in agency about its mission Agencies don’t mechanically/automatically and “scientifically” establish/implement policy They have a range of policy options and discretion to choose Agencies don’t always use their discretion wisely Admin law/judicial review is an attempt to respond to these problems We don’t have to assume judges make better administrators than agency employees do We just have to assume administrators will do better if they know a powerful third party is looking over their shoulder – H.L. Mencken quote near top of p. 332 Technicalities of Judicial Review Access – threshold issues to determine whether or not a court will even hear your cause Ripeness (of the issue/cause) Abbott Labs v Gardner (1967) Timeliness – Courts don’t anticipate harms Are facts fully developed? Parties will address the law’s actual, as opposed to potential or theoretical, impact [this requirement must be balanced by “law of equity” considerations] of administrative remedies – has plaintiff pursued all avenues w/in the agency for relief before coming to court? exhaustion Access Standing (of plaintiff) Adversariness – “case/controversy” requirement of Art. III, Sec. 2 – APA §702 much looser than con law standard which requires “direct” and “substantial” injury claim “A person suffering legal wrong because of agency action, or adversely affected or aggrieved by agency action w/in the meaning of a relevant statute, is entitled to judicial review thereof.” “[No] action in a court of the U.S. . . . shall be dismissed . . . on the grounds that it is against the U.S. Injury – only have to show claim is w/in a “zone of interest” a statute intended agency regulations to protect Scenic Hudson Preservation Conf. V FPC (1965) – extended principle to “aesthetic, conservational, and recreational” interests Assoc. of Data Processing Service v Camp (1970) involved economic loss due to competition (which results from agency action) U.S. v SCRAP (1973) – challenging “attenuated” relationship between freight rate increase and litter in the environment Injury – any class of interests the statute implicitly or explicitly requires the agency to consider in policy making Bennett v Spear (1997) – challenge to negative impact of Endangered Species Act implementation on operation of water reclamation/irrigation project FEC v Akins (1998) – admin law equivalent of a “taxpayers’ suit,” which is not allowed in con law context unless qualifying under Flast v Cohen (1968) exception to such suits arising under taxing/spending power violated specific constitutional limitation on govt. taxing/spending power Injury Access Standing (of plaintiff) Adversariness Injury Remediability – Court can fashion a remedy to relieve the plaintiff Plaintiff not estopped – hasn’t claimed/denied something previously that one is now claiming/denying: remember that the gov’t. can’t be estopped Issue not mooted – harms haven’t ceased since action initiated (Roe v Wade exception) Important Observations Doctrines related to “Access” are largely judiciallycreated standards serving as threshold or “gatekeeper” criteria to limit courts’ workload “Access” criteria can be [and have been] expanded or contracted to ease or tighten citizen access to courts “Liberal”/activist courts loosen the criteria making it easier for citizens to sue the govt. “Conservative” courts practicing judicial restraint tighten these criteria making it harder to sue The APA is an instrument to enhance supervision and control over the administrative state, thus it has some key provisions concerning judicial review of agency action and who may challenge agency action Judicial Review of Agency Actions (Chapter 7 APA) Is agency action reviewable? Y §702, §704 establishes "presumption of reviewability" N 701 (a) (1) statute prevents J.R. (2) “committed by law to agency discretion” Courts usually follow the wording of statutes granting non-reviewability of agency action [these are rare], except in cases where a constitutional issue or a fundamental right has supposedly been violated. “Committed by law to agency discretion” could be a serious wildcard; Court has waxed and waned on interpreting this phrase. The definition of an agency "action" extends from action through inaction. Scope of Review: § 706 Questions of Fact “Substantial Evidence” § 556-557 hearings De Novo Review Verification of Events Ascertaining Intent Determining Credibility of Witnesses Questions of Law •Statutory authority and obligation (ultra vires and discretion issues) •Procedural compliance Deference to Finding of Facts § 706(2) allows courts to void agency actions found to be (a) arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law; (e) unsupported by substantial evidence in a case subject to § 556-557 hearings or otherwise reviewed on the record of an agency hearing provided by statute; or (f) unwarranted by the facts to the extent that the facts are subject to trial de novo by the reviewing court. Unless there is a clear absence of substantial evidence (information that reasonable minds could accept as sufficient to support a rational conclusion), or there is serious challenge to the credibility of the evidence agency has relied upon, Courts will defer to agency’s findings. Deference to Agency Interpretation of Law § 706(2) allows courts to void agency actions found to be (b) contrary to constitutional right, power, privilege, or immunity; (c) in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority, or limitations, or short of statutory right; (d) without observance of procedure required by law Motor Vehicles Manuf. Assoc. v State Farm (1983) NHTSA adopted rule in 1977 requiring “passive” safety system (either airbags or seatbelts) in all cars manufactured after Sept., 1982 By 1981 it was clear that almost all new cars had seatbelts, rather than expected 60%-40% split Reagan’s new NHTSA head then rescinded the rule before its effective date Safety benefits of airbags would not be realized Automatic seatbelts too easily disabled Thus, no real safety benefits accrue BUT c. $1 billion cost to consumers from implementation of rule would depress auto sales and poison public’s attitude toward safety regs in general State Farm sued to prohibit application of the new rule (rescinding the original rule) and to compel the application of the original rule The new rule, as was the case with the original rule, was made under APA §553 No allegations of procedural irregularities or agency excess of statutory authority Rather, claim of “arbitrary & capricious” rulemaking (revoking rule w/o justification and in way as to thwart congressional intent) Agency’s authorizing statute provides for judicial review of agency “action” Court holds “action” to include “revoking” a regulation as well as imposing one Court’s ruling: Agency action is “arbitrary and capricious” which is prohibited by §706(2)(A) of the APA What constitutes “a/c” action? No rational relationship between facts found and choice made Agency relied on factors Congress didn’t want considered Agency ignored important aspects of the problems it’s charged with addressing What made NHTSA’s action “a/c”? Didn’t explain why rule couldn’t require air bags agency’s lawyers supplied this ex post facto rationale in brief no evidence the agency had relied on this line of reasoning in decision-making process Agency didn’t explain why it couldn’t require some kind of non-detachable automatic seat belt Agency rejected statistical evidence it had before it as invalid but didn’t conduct alternative studies to resolve uncertainties over the impact that the original rule would have on seat belt use Note: this case came a year BEFORE the Chevron case covered in Ch. 4 Chevron v Natural Resources Council (1984) Facts: EPA issued national standards for air pollution levels. Congress then required states which had not met standards to require industries within their borders to obtain state permits for the addition and operation of certain sources of pollution, “major stationary sources.” EPA, pursuant to rulemaking authority delegated to it in the statute to “implement the permit requirement,” allowed states to define an entire plant, rather than individual machines w/in it, to constitute “major stationary source”; this came to be referred to as the “bubble concept.” This allowed EPA to monitor only a plant’s total emissions for compliance with pollution standards. NRDC’s claim: EPA acted outside its statutory authority by adopting this rule, i.e., when Congress passed the statute imposing requirements on states lagging behind national clean air standards, the clear meaning of its words and clear intent was to require a separate permit for each pollution-emitting machine. Court’s ruling: an agency’s interpretation of its statutory authority must be upheld unless it is in violation of precise language in the statute. Language of statute is ambiguous, i.e., “major stationary source” is never defined Agency’s interpretation is “a permissible construction of the statute” and not “manifestly contrary to the statute.” Case’s significance: in the realm of administrative law, the principle of “judicial restraint” in reviewing agency action reigns supreme. This is the chief dimension of the “deference doctrine.” this ruling has been cited in more than 10,000 cases since deference doctrine does NOT extent to agency interpretation of constitutional and other legal principles, only its own statutory authority Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v Volpe (1971) Sec. of DOT can approve highways through public parks only if “no feasible and prudent” alternative exits even then, he must make every effort to ensure minimum harm to the park Volpe, Sec. of Transportation, approved construction of I-40 through Overton Park (containing the Memphis Zoo) w/o any formal factual findings on either of these points. Citizens’ group claims violation of authorizing statute