The USA, 1919-41 Depth Study: How far did US society change in

advertisement

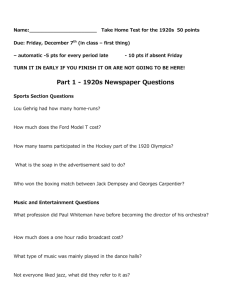

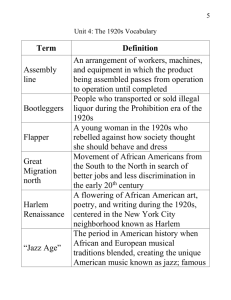

Cambridge ICGSE History Depth Study: The USA, 1919-41 How far did US society change in the 1920s? The Revolutionary Spirit of 1919 “The most extraordinary phenomenon of the present time … is the unprecedented revolt of the rank and file…. The common man … losing faith in the old leadership, has experienced a new access of self-confidence, or at least a new recklessness, a readiness to take chances on his own account … authority cannot any longer be imposed from above; it comes automatically from below.” —The Nation (25 October 1919) Solidarity (30 June 1917) The American ruling class saw radical ideas as foreign to the US, conflating reactionary and xenophobic feelings in the public’s imagination. The Seattle General Strike To win higher wages, 100,000 workers brought the city of Seattle, Washington to a halt. The General Strike Committee set up 35 neighborhood milk stations, prepared and served 30,000 meals per day, and organized an unarmed Labor War Veteran’s Guard to keep the peace. Firemen stayed on the job, and laundry workers continued to wash hospital laundry. During the five days of the strike, the city was quiet and orderly with a lower crime rate than before the strike. The Post Intelligencer (6 February 1919) After the strike, police raided the Socialist Party headquarters and arrested 39 members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). “The so-called sympathetic Seattle strike was an attempted revolution. That there was no violence does not alter the fact…. The intent, openly and covertly announced, was for the overthrow of the industrial system; here first, then everywhere…. True, there were no flashing guns, no bombs, no killings. Revolution, I repeat, doesn’t need violence. The general strike, as practiced in Seattle, is of itself the weapon of revolution, all the more dangerous because quiet. To succeed, it must suspend everything; stop the entire life stream of a community…. That is to say, it puts the government out of operation. And that is all there is to revolt— no matter how achieved.” —Ole Hanson, Mayor of Seattle Ole Hanson An Attentat (Propaganda of the Deed) Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s House after the bomb explosion (2 June 1919). From April to June 1919, anarchists carried out a series of bombings and attempted bombings. “The powers that be make no secret of their will to stop, here in America, the world-wide spread of revolution. The powers that be must reckon that they will have to accept the fight they have provoked. A time when the social question's solution can be delayed no longer; class war is on…. There will be bloodshed; we will not dodge; there will have to be murder: we will kill, because it is necessary; there will have to be destruction; we will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions. ” —The Anarchist Fighters The Steel Strike (September 1919) More than 350,000 workers in the steel mills of western Pennsylvania, who worked 12hour days, 6-days a week, went out on strike, defying US President Woodrow Wilson and American Federation of Labor President Samuel. The police beat and arrested strikers; the Department of Justice deported strikers; federal troops protected the steel mills. Owners of the steel corporations brought in 30,000 Black strikebreakers. Striking Chicago Steelworkers (1919) The steel corporations also employed spies to stir up hatred between Serbian and Italian strikers. After 10 weeks, the strikers called off the strike in defeat. The Murder of Wesley Everest In Centralia, Washington, on 11 November 1919, members of the American Legion attacked the IWW, the anti-war union that had been organizing the local lumber industry workers. The Legion marched with to the IWW hall armed with rubber hoses and gas pipes. A gun battle broke out in which 3 American Legion members were killed. Wesley Everest, an IWW member, lumberjack, and war veteran, killed a fourth Legion member, attempting to escape the gun battle. Everest was tortured and jailed. That night, vigilantes broke into the jail. The vigilantes cut off Everest’s genitals, hanged him from a bridge, and riddled his body with bullets. Wesley Everest No one was arrested for the murder of Wesley Everest, but 7 members of the IWW were sentenced to 25 to 40 years in prison for the deaths of the American Legion members. Preventing Mass Rebellion In 1919, 120,000 textile workers went on strike in New England; 30,000 silk workers went on strike in New Jersey; the police went on strike in Boston; cigarmakers, shirtmakers, carpenters, bakers, teamsters, and barbers went on strike in New York; 5,000 workers at International Harvesters in Chicago went on strike. These strikes were beaten down by force. The IWW was destroyed. The Socialist Party fell apart. The economy improved for just enough people to prevent mass rebellion. Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge (later US President) inspects the militia during the Boston Police Strike (1919). A Crusade for Conformity • In Washington, DC, a ’crowd burst into cheering and hand clapping’ when an irate citizen shot a critic of a patriotic pageant. • In Indiana, a jury took two minutes to acquit a citizen for killing a man who had said, ‘To hell with the United States.’ • In Connecticut, a salesman for a clothing store was sent to prison for calling Lenin ‘one of the brainiest’ men in the world. • The nation’s most powerful evangelist, Billy Sunday said, “If I had my way with those ornery wild-eyed socialists, I would stand them up before a firing squad.” • Senator McKellar of Tennessee advocated the establishment of a penal colony on Guam for political prisoners. • The New York State legislature expelled its five Socialist members despite the legal status of the Socialist party. “The Red Scare” and “The Palmer Raids” Beginning in December 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer conducted mass arrests of aliens (immigrants who were not citizens). Department of Justice agents broke into private homes and union halls without warrants and rounded up thousands of suspected radical aliens, including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. The arrested aliens were held in seclusion for long periods of time, brought into secret hearings, and ordered deported. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman “We must purify the sources of America’s population and keep it pure. I am myself an American and I love to preach my doctrine … undiluted Americanism.” —Attorney General Palmer Andrea Salsedo In the spring of 1920, Andrea Salsedo, an Italian typesetter and anarchist suspected of being involved in the 1919 bombings, was arrested in New York by FBI agents. The suspect was held for eight weeks in the FBI offices on the fourteenth floor of the Park Row Building and was not allowed to contact family or friends or lawyers. Then his crushed body was found on the pavement below the building and the FBI said he had committed suicide by jumping from the fourteenth floor window. Andrea Salsedo In Boston, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian friends of Salsedo, heard of their friend’s death and began carrying guns to protect themselves. Sacco and Vanzetti On 5 May 1920, in Massachusetts, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested, charged with a payroll robbery and with the murder of the payroll guards. Sacco and Vanzetti were convicted more for being anarchists and foreigners than from the evidence. Judge Webster Thayer, who presided, declared that he wanted to get “those anarchist bastards.” They spent seven years in jail while appeals went on, and while all over the country and the world, people became involved in their case. On 23 August 1927, Sacco and Vanzetti were electrocuted. Sacco (right) and Vanzetti (left) Woody Guthrie’s “The Flood and the Storm” historically contextualized the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. Woody Guthrie’s “The Flood and the Storm” • The year now is Nineteen and Twenty, kind friends, and the great world’s war we have won. • Old Kaiser Bill, we have beat him once again in the smoke of the canon and the gun. • Old Von Hindenburg and his Royal German Army, they are tramps in tatters and in rags. • Uncle Sammy has tied every nation in this world in his long, old leather moneybags. • Wilson caught a trip and a train into Paris, meeting Lloyd George and Mister Clemenceau. • They said to Mister Wilson, “We’ve staked off our claims. There is nothing else for you.” • “I plowed more lands, I built bigger factories, and I stopped Hindenburg in his tracks. • You thank the Yanks by claiming all the lands, but you still owe your money to my bank.” • “Keep sending your ships across these waters. We’ll borrow all the money you can lend. • We must buy new clothes, new plows and factories, and we need golden dollars for to spend.” • Every dollar in the world, well, it rolled and it rolled and it rolled into Uncle Sammy’s door. • A few got richer and richer and richer, but the poor folks kept but getting poor. • Well, the workers in the world did fight a revolution to chase out the gamblers from their land. • Farmers and peasants and workers in the city fought together on their five-year plans. • The soul and the spirit of the workers’ revolution spread across every nation in this world • From Italy to China to Europe and to India, and the blood of the workers it did spill. • This spirit split the wind to Boston, Massachusetts with Coolidge on the governor’s chair. • The troopers and soldiers, the guards and spies fought the workers that brought the spirit there. • Sacco and Vanzetti had preached to the workers. They were carried up to Old Judge Thayer. • They were charged with killing the payroll guards, and they died in the Charlestown chair. • Sacco had come from the mountains of Italy, had a wife and children three. • Vanzetti sold fish on the streets of North Plymouth, was a writer of workers’ poetry. • Well, the world shook harder on the night they died than ’twas shaken by that great world’s war. • More millions did march for Sacco and Vanzetti than did march for the great warlords. • More millions did pray, more millions, they did sing, more millions, they did weep and cry • This August night in Nineteen and Twenty-Seven when strapped there in that chair they did die. • More millions saw the light, more millions joined the fight, more millions from shore unto shore • Than ever did fight for the rich man’s hire or dress in the warrior’s uniform. • Well, the peasants, the farmers, the towns and the cities, and the hills and the valleys, they did ring. • Hindenburg and Wilson, and Harding, Hoover, Coolidge never heard this many voices sing. • The zigzag lightning, the rumbles of the thunder, and the singing of the clouds blowing by, • The flood and the storm for Sacco and Vanzetti caused the rich man to pull his hair and cry. Ending the “Dangerous and Turbulent” Flood of Immigrants Between 1900 and 1920, 14 million immigrants had come to the US. In 1921 and 1924, the US Congress passed laws setting immigration quotas favoring Anglo-Saxons, severely limiting the coming of Jews, Latins, and Slavs, and keeping out Asians and Blacks. Effect of 1921/1924 Immigration Laws Germany: 51,227 England/Northern Ireland: 34,007 Irish Free State: 28,567 Italy: 3,845 Russia: 2,248 Lithuania: 124 African Countries: 100 each Bulgaria: 100 China: 100 Palestine: 100 The “American Plan” As the radical left was destroyed, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) lost its appeal to business as a safe alternative to socialism; between 1920 and 1930, membership in the AFL dropped from 5 million to less than 3 million. The National Association of Manufacturers mobilized a movement for its “American Plan” that would replace “union shops” with “open shops.” Workers were forced to sign “yellow dog” contracts; court injunctions made strikes and picketing almost impossible. Corporations established company unions as part of an effort to create a sense of team loyalty with the help of newly-introduced personnel managers, a product of the business schools of the decade. Between 1919 and 1924, 117 colleges opened business schools dedicated to scientific management and business administration. A New Kind of Hero The Saturday Evening Post told the new urban-industrial middle class that sustaining order demanded administrative heroes, such as the wartime administrator of food supplies Herbert Hoover, said to have given the country “clean, efficient action” at “incredibly low cost.” In the Saturday Evening Post, Hoover was praised “as a machine of a man, with no waste words or motion, who was organizing a machine of men, … [to] take over existing organizations and run them with a minimum of human friction and a maximum of practical results.” The Purity Crusade and Prohibition The Purity Crusade was a movement of evangelical Protestants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Purity Crusaders sought to defend public morals by spreading Protestant Christianity; by legally enforcing the observance of the Sabbath; by separating the home from public life so as to shield innocent children from the corruption of outsiders; by controlling sexuality, including the prohibition of abortion, the avoidance of masturbation, the replacement of midwives by doctors, and the elimination of prostitution; by criminalizing drugs and alcohol; by segregating the races and religions; and by instilling loyalty to the nation. Temperance movement supporters within the Purity Crusade successfully lobbied for the ratification of the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution (enabled by the Volstead Act), effectively prohibiting alcoholic beverages in the US. Prohibition began 17 January 1920 and ended 15 December 1933, when the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition went into effect. Prohibition gained widespread approval in some states, particularly the rural areas in the Midwest, although in urban states it was not popular. Levels of alcohol consumption fell by about 30 percent in the early 1920s. Every year during prohibition, federal agents seized thousands of illegal distilleries, confiscated hundreds of thousands of gallons of illegal spirits, and arrested tens of thousands of offenders. Despite the work of these agents, however, prohibition proved impossible to enforce effectively. Millions of Americans, particularly in urban areas, were simply not prepared to obey the law. Prohibition Agents Dispose of Spirits Illegal stills (distilleries) sprang up all over the US as people made their own illegal whisky (moonshine). Most Americans had no need for their own still. They simply went to their favorite speakeasy. Crime and Corruption Speakeasies were well supplied by bootleggers (suppliers of illegal alcohol) who made vast fortunes. Chicago gangster boss Al Capone made around $60 million a year from his speakeasies. By 1925 there were more speakeasies in American cities than there had been saloons in 1919. Prohibition led to massive corruption. Many of the law enforcement officers were themselves involved with the liquor trade. Big breweries stayed in business throughout the prohibition era by bribing local government officials, prohibition agents, and the police. Even when arrests were made, it was difficult to get convictions because of corrupt judges. Al Capone (c. 1935) Clive Weed, “The National Gesture,” Judge (12 June 1926) Classes Mix at the Speakeasy In the larger cities nightclubs sold bootleg liquor and featured jazz entertainment as the Purity Crusade, which had gained momentum in the decades before 1920, seemed entirely forgotten. Jazz Musician Milton Mezzrow “It struck me funny how the top and bottom crusts in society were always getting together during the Prohibition era. In this swanky club which was run by the notorious Purple Gang, Detroit’s bluebloods used to congregate— the Grosse Point mob on the slumming kick, rubbing elbows with Louis the Wop’s mob.” —Milton Mezzrow The End of Prohibition Prohibition had made the US lawless, the police corrupt, and the gangsters rich and powerful. By the end of the 1920s, “The Noble Experiment” had failed. When the Wall Street Crash was followed by the Great Depression, economic arguments were presented for ending prohibition. Legalizing alcohol would create jobs, raise tax revenue, and free up resources tied up in the impossible task of enforcing prohibition. Prohibition was repealed in December 1933. Al Capone’s Soup Kitchen (1931) “Universal Newspaper Newsreel” (1933) The Interchurch World Movement President Woodrow Wilson exhorted Americans to bring America’s Purity Crusade to a climax by purging evil and darkness from the entire world. During 1919 and 1920, Protestant churches planned to fulfill Wilson’s exhortations through an Interchurch World Movement that would fill every nation in the world with missionaries. Protestant leader Tyler Dennett proclaimed: “Our business is to establish a civilization that is Christian in spirit and in passion in Borneo as much as in Boston.” Barely two years later, these words sounded hollow. Protestants appeared disillusioned and confused as they entered the 1920s. Suddenly, they faced a world that refused to be redeemed, and the great financial drive to mobilize resources for the missionary effort failed. Students, who earlier had rushed to volunteer for missionary duty, decided to stay home. Demoralized, Protestants suffered another shattering experience when their own respectable middle-class church people refused to uphold the Eighteenth Amendment and keep America free from the influence of alcohol. Hope and Disillusionment As the American geographic frontier closed in the 1890s, an industrial frontier opened. Optimistic social scientists promised that industrialism would destroy all irrational historical cultures and liberate the individual. Abandoning biblical fundamentalism, liberal Protestants accepted the idea of evolution, which was identified with progress and the final triumph of Protestantism. The American war effort in WWI was to liberate all people, representing an American internationalism. Their optimism shattered by World War I, older social scientists abandoned internationalism for isolation, giving up the hope that the entire world could be brought into industrial rationality but continuing to hope that this could be the future of the US. Many younger poets and novelists of the 1920s—the “lost generation”—were even more bitterly disillusioned, giving up hope even for America’s future. The Great Gatsby (1925) The hero of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, James Gatz, leaves the closing agricultural frontier of North Dakota for the industrial frontier of New York City, described as a “valley of ashes.” In this frontier of ugliness and decadence, Gatsby must restore Daisy, a girl whom he loved before he went to the war, to her original virginity. He must persuade her of the unreality of her marriage to another man while he was away and of the unreality of her motherhood. But instead of a rational and predictable world, Gatsby is caught up by circumstance; an automobile accident sets a chain of events in motion in which a man kills Gatsby because he mistakenly believes Gatsby was the driver of the car The Great Gatsby that killed his wife. A Farewell to Arms (1929) Ernest Hemingway had been physically wounded in Italy during the war. In contrast to the industrial frontier’s promise of progressive linear time, the war had forced him to confront death, the possibility of the cyclical nature of time, the cycle of birth inevitably followed by death. In Hemingway’s novel A Farewell to Arms, when the hero, Frederick Henry, deserts the insanity of the war and takes refuge in Switzerland with Catherine, the nurse he has loved, they live happily through the winter. But spring brings the birth and death of a child and Catherine. A Farewell to Arms U.S.A. Trilogy (1930, 1932, 1936) For John Dos Passos, the insanity of the armies continued into the insanity of the corporations of the 1920s. Americans had believed that armies could operate rationally and bring liberation, They had believed much the same about corporations. In reality, Dos Passos writes in his novel Three Soldiers, “men seemed to have shrunk in stature before the vastness of the mechanical contrivances they had invented— men had become antlike.” Dos Passos best expressed the “lost generation’s” horror of organization in his massive USA. Having lost faith in the urban-industrial frontier of his Progressive fathers, Dos Passos had no space to flee to escape these fathers. U.S.A. Trilogy In USA, Dos Passos wrote, “The transcontinental passenger thinks contracts, profits, vacation trips, mighty continent between Atlantic and Pacific, power, wires humming, dollars, cities jammed, hills empty, the Indian trail leading into the wagon road, the macadam pike, the concrete skyway, transcontinental planes, history, the billion dollar speed up. And in the bumpy air over the desert ranges toward Las Vegas sickens and vomits into the carton container the steak and mushrooms he ate in New York.” The son of this corrupt father stands as a solitary vagabond on a highway beneath the plane. Trying to hitch a ride, he is a dropout who “went to school, books said opportunity, ads promised speed, own your own home, shine bigger than your neighbor, the radio crooner whispered, girls, ghosts of platinum girls coaxed from the screen, millions in winnings were chalked upon the board, in the offices, pay checks for hands willing to work; the cleared desk of an executive with three telephones on it—he waits with swimming head, needs knot his belly, idle hands numb, beside the speeding traffic.” Sensual Music The conservative middle class could not stop young people from listening and dancing to sensual music. African rhythms began to influence white popular music in the 1890s. Ragtime was a musical style in which the piano captured the patterns of the African drum. As the audience for this music grew, the lyrics of songs began to change; they became much more explicitly sexual. Sheet music sold widely and dance crazes swept through cities in the years immediately before WWI. In the 1920s, blues and jazz were even more sensual and consequently threatening. “How Jazz Was Born” (1948) The Jazz Age Many newspapers and magazines agreed to try to halt the spreading influence of jazz through a conspiracy of silence, only reporting that it was a dying fad. When this proved ineffective, conservative authorities tried to have the music repressed. By 1929, many cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Detroit, and Kansas City, had regulations prohibiting jazz from public dance halls. The attempt to prohibit jazz only increased its appeal to the young, who were in self-conscious rebellion against their parents and were searching for other ways of experiencing the rhythm of life. “Hot Feet” (1929) The Appeal of Jazz For the first time in American history, whites seemed to express an appreciation for Black culture but continued to stereotype Blacks. They ascribed a primitiveness to Black culture and demanded that Blacks function as Christlike salvation figures. In a world where traditional idealism had vanished, where traditional religion seemed bankrupt, Black primitivism, outside of white culture, offered a new spiritual meaning, a new salvation. Young white musicians saw in jazz a symbolic alternative to the bureaucratic prison of their fathers. Jazz had a structure that offered an opportunity to improvise and was a way out of chaos into a new world of meaning. Eddie Condon Hoagy Carmichael Eddie Condon, who taught himself to play jazz by ear, reported his father’s reaction: “You are terrible and you can’t read music.” Condon’s reply to his father was, “What’s that got to do with being a musician?” Louis Armstrong “Don’t Forget to Mess Around” (16 June 1926) Hoagy Carmichael smoked marijuana and listened to jazz. He described what it felt like: “My body got light. Every note that Louis [Armstrong] hit was perfection. I ran to the piano. They swang into ‘Royal Garden Blues.’ I has never heard the tune before but somehow I knew every note. I couldn’t miss. I was floating in a strong deepblue whirlpool of jazz. It wasn’t the marijuana. It was the music. The music took me and had me and it made me right.” To participate in jazz was to live more fully. Music that expressed an immediate experience of sorrow and joy, of disharmony or harmony with the universe, was religious music. Unlike most white religion, jazz presented worship as a pleasurable activity and a release from tension. Even the white musician Paul Whiteman, who presented a commercialized and extremely restrained and prettified jazz to white audiences, sensed some of this meaning. “Jazz is at once a revolt and a release. This cheerfulness of despair is deep in America. That is the thing expressed by the wail, that longing, that pain behind all the surface clamor and rhythm and energy of jazz.”—Paul Whiteman Paul Whiteman’s Saxophone Sextet (c. 1922) The Roaring Twenties The 1920s in the US are often called the Roaring Twenties, suggesting a time of riotous fun, because the entertainment industry blossomed. A Group of Radio Listeners (c. 1925) Radio: Almost everyone in the US listened to radio. Most household had their own set. People who could not afford to buy one outright could purchase one on installments. In 1921, there was only one licensed radio station in America. By the end of 1922 there were 508. By 1929, the NBC radio network was making $150 million a year. In Hollywood, California, a major film industry developed. New stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton made audiences roar with laughter, while Douglas Fairbanks thrilled them in daring adventure films. The cinema quickly discovered the selling power of sex. The first cinema stars to be sold on sex appeal were Theda Bara and Clara Bow. Male stars, too, such as Rudolph Valentino, were presented as sex symbols. Until 1927 all movies were silent. The first “talkie” is considered to be Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer. During the 1920s movies became a multi-billion dollar business, and it is estimated that a hundred million cinema tickets were sold each week by the end of the decade. Theda Bara Clara Bow Rudolph Valentino Baseball, boxing, and football became popular and lucrative entertainments in the 1920s. Jack Dempsey Jim Thorpe Babe Ruth The motor car carried their owners to and from their entertainments and to an increasing range of sporting events, beach holidays, shopping trips, picnics in the country, or simply on visits to family and friends. Premarital Sex and Divorce The divorce rate of the middle class had increased steadily from 1890 to 1920; it would double in the 1920s. A Postcard Depicts the Loosening Morals of the 1920s “None of the mothers had any idea how casually their daughters were accustomed to be kissed.”—F. Scott Fitzgerald The urban middle class had stopped chaperoning its daughters after 1900, and there was a tremendous decline in the pattern of premarital virginity by 1920. It was clear that by 1910 a new code of permissiveness was being elaborated by the young. Soon unchaperoned, sexual intimacy became acceptable within the context of an affectionate relationship that might result in marriage. The Flapper The flappers were independent, adventurous young women. They wore short dresses and make-up. They smoked in public. Flappers were described as “expensive and about nineteen” having “a jitney body and a limousine mind.” Flapper Magazine Flappers (1922) Howard University Flappers (1920) The American Birth Control League Despite this sexual revolution, birth rates significantly declined. Margaret Sanger brought the growing interest in contraception into the open with the publication of her magazine The Woman Rebel, dedicated to the liberation of “women enslaved by the machine, by wage slavery, by bourgeois morality, by customs, laws, and superstitions,” and advocating “the prevention of conception” by imparting adequate knowledge to its middle class readers. By 1921, her efforts were achieving respectability in the American Birth Control League, supported financially by younger wealthy women. Sanger violated the law by starting birth-control clinics for lower-class women: “Mothers! Can you afford a large family? Do you want more children? If not why do you have them?” Margaret Sanger The Nineteenth Amendment Women had finally, after long agitation, won the right to vote in 1920 with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, but voting was still a middle-class and upper class activity. Women’s Studies pioneer Eleanor Flexner said the effect of female suffrage was that “women have shown the same tendency to divide along orthodox party lines as male voters.” Suffragettes Marching (1920) “There is no hope even that woman, with her right to vote, will ever purify politics…. If voting changed anything, they’d make it illegal.”—Emma Goldman The Ku Klux Klan After the US Civil War (1861-65), scattered groups of whites in the South called themselves the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, but these local groups were not able to create a widespread organization. In Georgia in 1915 after the release of The Birth of a Nation, a film glorifying the Klan praised by President Wilson, a cohesive and interlocking Klan was established that would become a national organization as strong in much of the Midwest as it was in the South. It was dedicated to carrying its anti-Black crusade to the North and to placing the same kinds of restraints on Catholics and Jews. By 1924, the Ku Klux Klan had 4.5 million members. Left: A KKK march in Washington, DC (1925); Right: KKK horsemen in New Jersey (c. 1920) The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill Lynching, when a mob hangs a person for an alleged offense without a legal trial, was not infrequent in the US. While lynching was not confined to Blacks, lynching victims were disproportionately Black. Beginning in 1921, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sponsored anti-lynching legislation such as the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill and numerous other proposals to make lynching a federal crime, providing fines and imprisonment for persons convicted of lynching in federal courts and fines and penalties against states, counties, and towns which failed to use reasonable efforts to protect citizens from mob violence. While the legislation passed in the House of Representatives in 1922, it was killed in the Senate. Southern Senators claimed a federal ban on lynching was “unconstitutional” and “a A Lynching in Mannford, Oklahoma (c. 1921) violation of states’ rights.” The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 The single worst incident of racial violence in US history occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma on 31 May and 1 June, 1921. The Greenwood District of Tulsa, 35 city blocks housing the wealthiest Black community in the United States known as “the Black Wall Street,” was burned to the ground: 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire leaving 10,000 Blacks homeless. At the time, the official death toll was less than 40, but an investigation published in 2001 found evidence that as many as 300 Blacks were murdered during the riot. The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 Racism in the United States In colonial Virginia in 1676, opponents of the governor and the wealthy planters, led by Nathaniel Bacon, offered freedom to both white indentured servants and to Black slaves who were prepared to help seize control of the colony. The motives of the rebels in Bacon’s Rebellion were mixed—one of their demands was for war to seize more land from the Indians. But their actions showed how poor whites and Africans could unite against the landowners. The response of the colonial landowners was to push through measures which divided the two groups. The Virginian House of Burgesses sought to strengthen the racial barrier between English servants and African slaves. The Burning of Jamestown (1676) In other words, the planters recognized that far from white and Black automatically hating each other, there was a likelihood of some whites establishing close relations with the slaves—and the colonial authorities sought to stamp this out. It was now that racism began to develop as an ideology in America. The ruling class recognized racism as a means to maintain their position. As the American colonies developed into a capitalist nation state, the ideology of racism became the central hegemonic strategy by which the ruling class of the United States maintains its position. Racism divides the ruled. Racial divisions mask the underlying class divisions in US society. Racism unites whites across class divides. Racism, rather than being dysfunctional, supports the hegemonic status quo, preserving the ruling class. This means that, despite efforts to overcome racial divisions, racism remains prominent in the contemporary United States. Attempting to end racism in the United States would involve a direct, counterhegemonic attack on the logic of the capitalist nation state. Thus, Blacks or whites who dare to cross the color boundary are threats to be eliminated. Paul Robeson Paul Robeson became world famous in the 1920s, and he traded his cachet to mobilize progressives in support of civil rights for Blacks, economic rights for workers, and human rights for all oppressed peoples. Born in 1898, Robeson was the son of a former Black slave. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1923, but racism prevented him from practicing law. He was a professional football player, a professional concert and recording artist, a professional film and stage actor. He spoke and wrote more than twenty languages. Because of his political activism, he was blacklisted; a mob tried to kill him in 1949; the US Government revoked his passport in 1950; and the CIA attempted to assassinate him in 1961. “Ol’ Man River” •There’s an old man called the Mississippi; that’s the old man I don’t like to be! What does he care if the world’s got troubles? What does he care if the land ain’t free? •Ol’ Man River, that Ol’ Man River, he must know somethin’, but don’t say nothin’; he just keeps rollin’, he keeps on rollin’ along. •He don’t plant ‘taters, he don’t plant cotton, and them that plants ‘em is soon forgotten. But Ol’ Man River, he just keeps rollin’ along. •You and me, we sweat and strain, body all achin’ and racked with pain. “Tote that barge!” “Lift that bale!” You show a little grit and you’ll land in jail. •I keep laughin’ instead of cryin’; I must keep fightin’ until I’m dying. But Old Man River, he just keeps rollin' along. •That’s the old man that I’d like to be. •Get a little drunk and you’ll land in jail. •I get weary and sick of trying. I’m tired of living and scared of dying. Show Boat Film Poster (1936) The Harlem Renaissance Black creativity exploded in the 1920s as talented Blacks from across the country came into New York to participate in the Harlem Renaissance. Young composers, novelists, playwrights, and poets flowered in an environment of Black pride established by an older generation of intellectuals. The two generations agreed on the need for militancy, but they disagreed on the form of that militancy. If we must die—let it not be like hogs Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot, While around us bark the mad and hungry dogs, Making their mock at our accursed lot… Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back! —Claude McKay, “If We Must Die” Arthur Holitscher, Clara Zetkin & Claude McKay While sociologist and historian W.E.B. DuBois advocated economic radicalism, the older generation of Blacks affirmed strongly their commitment to Victorian sexual morality and to Christianity. The Black establishment of the 1920s, accepting the white definition of art as something created by an exceptional artist, dismissed Blues and Jazz as worthless, holding popular music in contempt. On the other hand, white patrons demanded an uncomplicated biological primitivism. Against these currents, the younger generation of Black artists struggled to define their sense of a Black cultural tradition. W. E. B. DuBois “I did not feel the rhythms of the primitive surging through me, and so I could not live and write as though I did. I was Chicago and Kansas City and Broadway and Harlem. And I was not what she wanted me to be.” —Langston Hughes Countee Cullen lamented in poetry. Jean Toomer and Nella Larsen wrote novels characterized by tortured soul-searching. Jean Toomer’s Cane Nella Larsen’s Quicksand I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind,… Yet do I marvel at this curious thing: To make a poet black, and bid him sing! —”Yet Do I Marvel” Countee Cullen reading poetry to children. Langston Hughes cautioned the Black writer must reject the implicit motivation “I want to be white.” Believing Black culture sprang from the masses, he embraced the Blues for inspiration: “To these the Negro artist can give his racial individuality, his heritage of rhythm and warmth, and his incongruous humor that so often, as in the Blues, becomes ironic laughter mixed with tears.” Prevented from bringing jazz on campus, Sterling Brown, a professor of English at Howard University reminded the respectable Black middle class of the reality of existence for most Black people in America: O Ma Rainey Li’l an’ low, Sing us ‘bout de hard luck Roun’ our do’: Sing us ‘bout de lonesome road We mus’ go…. Langston Hughes Sterling Brown —”Ma Rainey” Marcus Garvey Marcus Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914. Garvey believed it was impossible for Blacks to be equal in white America. He preached Black pride, racial separation, and a return to Africa, which held the only hope for Black unity and survival. In the meantime, he told Blacks to support each other by dealing only with Black businesses: UNIA organized groceries, laundries, restaurants, a printing plant, a hotel, and the Black Star Steamship Line. The US government deported Garvey in 1926. His nationalist movement collapsed with the coming of the Great Depression as Blacks, last hired and first fired, struggled for physical survival. Marcus Garvey (1924) Revision Questions • What were the “Roaring Twenties”? • How did film and other media develop in the 1920s? • How far did the roles of women change during the 1920s? • How widespread was intolerance in US society? • What restrictions were placed on immigration? • What was “The Red Scare”? • How and why did religious intolerance spread? • Why was there discrimination against Black Americans? • What was the influence of the Ku Klux Klan? • Why was Prohibition introduced and then later repealed? • How did Prohibition contribute to the rise of gangsterism in the 1920s?