Intellectual Change

advertisement

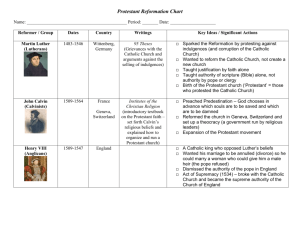

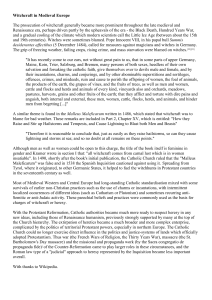

Intellectual change Mark Knights Ideas and contexts • Could study ‘great thinkers’ and examine their ideas; they are indeed part of the story but • Ideas don’t change in isolation from events and movements around them • Ideas aren’t just the preserve of ‘intellectuals’ but are inherent in everyday actions, conflicts and beliefs • So let’s look at the ‘big themes’ of the module and explore how they changed assumptions and ideologies • But with the caveat that a focus on change must not obscure continuity over the period Theme 1: Church and State • We have been exploring major changes in the church (Protestant and Catholic Reformations) that were also ideological • We have been examining the development of the state: its growing fiscalmilitary capacity, the ideologies of its rulers • We have been analysing the interaction of church and state: riots, rebellions, revolts and revolutions The related problems of C16th French wars of religion, the revolt of the United Provinces and C17th revolutionary Britain – Religious pluralism and friction – Fundamental rethinking of the grounds of obedience, forms of government and the right to resist Religious pluralism • Catholic vs Protestant but also the fracturing of protestantism, leading to protestant against protestant • The destruction of religious unity; simultaneous and conflicting claims to be ‘true’ • What is the correct response? – Represssion, enforced uniformity? Very difficult for protestants wanting to avoid accusation of behaving like catholics. Solution adopted for much of the C16th and in England after 1660 and France after 1685. Culture of unity and uniformity. – Toleration/freedom of conscience? Solution adopted in United Provinces, France 1598, England 1689. Recognition of diversity and plurality. How to justify freedom of conscience? • Dutch Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677, of Portuguese-Jewish background), whose Theological-Political Treatise (1670) argued for freedom of thought and conscience • or Locke’s Letters on Toleration (early 1690s) • or the Huguenots and protestant sects • Arguments: – You cannot compel the conscience (which is in any case God-given) – Restricting freedom of conscience is popish and prevents the revelation of truth – The church hierarchy have a vested interest in their own power and in promoting ceremonies and rituals that are not necessary to salvation (these things are also popish) – A church is a voluntary society; the state should retreat from the realm of religious belief. – Love your neighbour; God created men free – Or reject Bible and see God as nature or non-Christian – It promotes commerce and wealth Hostility to freedom of conscience • • • • In France the Edict of Nantes took a long time to be registered in regional parlements – 1609 Rouen; disliked by catholic majority Duty to avoid heresy and prevent subjects falling into error that will lead them to damnation; without guidance they will not achieve salvation and will fall into superstition, irreligion and immorality. National churches are therefore necessary. Freedom of conscience is only a cover for political sedition and the two go hand in hand. How tolerant were France, UP and England anyway? are catholics tolerable? How far a move towards separation of church and state? How far does it produce or reflect a decline of religious zeal? Resistance theory Why should you obey a secular authority that persecutes or proscribes your religion? or which cannot provide you with security? • The orthodox answer: – The king is divinely appointed; he is empowered by God; God requires obedience; disobedience is sinful; – The king is sovereign and all powerful; he does not share power with the people; people certainly have no right to hold the king to account (God alone will judge him), and even less right to resist him; the king’s will is law – Monarchy is the most natural form of government Re-thinking the grounds of obedience and authority • There were several ways in which that view was challenged – The Calvinistic defence of religion: private individuals cannot resist, but there may be institutions that can; developed by his followers; Beza and the need to follow God’s law not man’s. – By appeal to an ancient constitution; legal scholarship recovering sense of unwritten national law embodying sets of privileges and immemorial customs; this was not a simple story of monarchical power but on the contrary a long history of a national assembly; idealisation of ancient liberty and even of popular sovereignty • Francois Hotman’s Francogallica (1573) ; Sir Edward Coke in England in early C17th; Pietor de Gregorio in Sicily; Francois Vranck in Netherlands (Corte Vertooninghe, 1587) A radical Protestant theory • • • • Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos or Defence of Liberty against Tyrants (1579): Possibly by Philippe Duplessis Mornay. He escaped 1572 massacre and fled to England, returning to France to aid Henri de Navarre (Henry IV); an active philosopher. contract; natural liberty and equality; natural law; consent as basis for civil society; popular sovereignty; right of resistance; moral not religious theory. State of nature [NB influence of overseas exploration and colonisation; Locke ‘in the beginning all the world was America’], natural freedom and equality Catholic resistance theory Catholic League needed arguments to favour the rejection of a protestant monarch, such as Henri de Navarre (who was excommunicated in 1585); but also other succession crises in Scotland and England. • Dominican and Jesuit. Francisco de Vitoria (1485-1546), Cardinal Bellarmine (1542-1611) and Francisco Suarez (1548-1617); Robert Persons in England (1580s); Juan de Mariana (1599) • Ideas: man not irredeemably evil; Suarez: law of nature ‘written in our minds by the hand of god’; discernible by reason; political society as artificial and man-made not god-given; therefore rested on consent of community; man by nature free and equal. Ideas about contract • civil society as man-made, artificially the result of contract, popular sovereignty • Hobbes (1651) an authoritarian version of this contract; the individual transfers all power to the sovereign • John Locke (1690) a liberal version of this contract; the individual entrusts power to an executive but retains both natural rights and a power to judge when the government is dissolved by tyranny; force against force Other implications of the Calvinistic reformation • Notions of the self: examination of one’s life to discern the signs of providence and hence if you were saved; more biographies and autobiographies • The waning of calvinism was even more powerful: the unleashing of the individual unrestrained by moral code? • Images and iconoclasm (here in Holland 1568) • • • The work ethic. Max Weber, Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-5): laziness was an affront to God; work ethic; giving money away as charity was useless so invest; turn away from magical explanations to scientific rationalism The waning of calvinism unleashed the spirit of capitalism – the pursuit of luxury was not sinful and helped produce wealth – a more secular society? The waning of calvinism also accompanied by a fundamental rethinking of God’s relationship with man: deism (Voltaire) and atheism, the decline of witchcraft Theme 2: Empiricism and reason • In part this develops out of the reformation process • But it had also preceded it, growing out of humanism, exploration and new scientific instruments and tools • Scientific instruments enabled new ways of thinking about the world – Telescope: new ideas about the earth and cosmos – The microscope [Robert Hooke, Micrographia (1665); Antony van Leeuwenhoek The earth • • • • Cleric Thomas Burnet at end of C17th went on Grand Tour and saw Alps: earth had to have been changed by natural processes over long periods of time; but still sought to reconcile this to the Biblical account. Opened debate about origin of earth which Bible put at 4004 BC. Woodward’s Essay Towards a Natural History of the Earth (1695) suggested that fossils were once living creatures and could be used to investigate the ancient history of the earth. Noah’s Flood as the explanation. Edward Llwyd’s Lithiphylacii Britannici Ichonographia (1699) mapped and classified fossils, without reference to the Bible. Sir Hans Sloane collected minerals, including those with pharmaceutical uses. How did ‘the new science’ impact more broadly on ideas? • Decline of witchcraft and decline of magic – – 1675-1750, saw decline. In the Dutch republic prosecutions came to an almost complete stop after 1600; in Spain the Inquisition stopped executing witches in wake of Basque witch-hunt of 1609-11; IN France numbers reduced greatly by 1620s; in England they tapered off after 1612, with the exception of a large hunt 1645-7; Scotland experienced its last large witch-hunt in 1661-2. Against this trend Hungary, Transylvania, Poland and New England (Salem) had widespread prosecutions only in late C17th and early C18th. 7 European countries took legislative action to remove witchcraft from statute book ege France 1682; Prussia 1714; GB 1736; Habsburg empire 1766; Russia 1770; Poland 1776; Sweden 1779. NB these often postdated end of witch craze; and they were not always particularly extensive measures. In England and France it remained illegal to pretend to exercise powers of witch or tell fortunes(only repealed in 1951). • A methodology for thinking applied to all realms of thought: Renée Descartes and Thomas Hobbes. Mathematical reasoning; minimising the power of language to distort meaning and understanding; certainty and probability; political science Theme 3: Communicative revolution? Was intellectual change the monopoly of the elite? • Improvements in transport, shrinks world, allows news to travel, urban/rural divide? • Printing press: ubiquitous in England and Holland by end of our period; end of censorship in these countries; facilitated newspapers, vehicle for the dissemination of ideas to a popular audience and a reflection of popular ideas; allowed both radical and conservative ideas to contest each other’s standpoints; force of public opinion • Broader public sphere, with some scope for women But • Focus has been on intellectual change in north west Europe (shift from first part of our period when southern Europe was instrumental in Renaissance) • Even there we can find not a single trajectory of change but a process of contested change, of very different outlooks jostling side by side; we can find a very strong strand of popular as well as elite loyalism to church and state • Outside of that region we could say that the pace of change was very much less certain • Which leave us with a question… When did early modernity end? • Do we say that the changes I have sketched amount to an early enlightenment that went on to usher in modernity? We can discern a weakening of the religious fervour, even the beginnings of a separation of church and state; the development of religious pluralism; the emergence of natural rights and ideologies of popular sovereignty and resistance; a scientific rationalism; a free press, a spirit of capitalism • Or do we want to stress the slow and uneven pace of change and insist that society is only modern when we find change across the social scale, across Europe as a whole, in rural as well as urban society? Are we still dealing with an ancien regime only swept away with the French revolution? in which case we might well push the beginning of modernity a lot later!