Microsoft Word - UWE Research Repository

advertisement

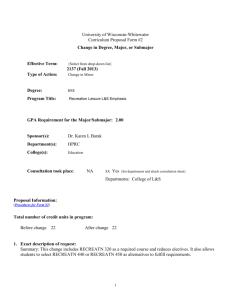

Differentiating Outdoor Recreation: Evidence Drawn from National Surveys in Scotland Nigel Curry, Countryside and Community Research Institute, Cheltenham and Katrina Brown, Macaulay land Use Research Institute, Aberdeen Corresponding Author: Professor Nigel Curry, Director, Countryside and Community Research Institute, Dunholme Villa The Park, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 2RH T: +44 (0) 1242 714126 F: +44 (0) 1242 714395 E: ncurry2@glos.ac.uk W: www.ccri.ac.uk 1|Page Differentiating Outdoor Recreation: Evidence Drawn from National Surveys in Scotland Abstract Outdoor recreation participation can be seen to fall into four identifiably different groups. Countryside outdoor recreation has been in decline for at least 25 years because of changing lifestyles and cultures, and targeted policy – which focuses heavily on the supply side - appears to have had little influence over consumption levels. Localised outdoor recreation is on the increase, accommodating ‘busier’ lives, in tandem with general national government policy health exhortations. Participation in community outdoor recreation, driven by community sport initiatives, heath referral schemes and the notion of the ‘green gym’ has remained more or less static over time, for a variety of different reasons. Market-based outdoor recreation participation fluctuates in line with changes in the economy, disposable incomes and commoditised cultures. Of these four outdoor recreation types in Scotland, localised outdoor recreation seems to offer the greatest potential for developing a more active Scottish population into the future, as part of policies concerned with exercise, diet, health and wellbeing. It is likely, however, that this approach will predominantly benefit the higher social grades. Drivers of outdoor recreation participation The purpose of this paper is to explore the extent to which there is an empirical basis for distinguishing different types of outdoor recreation according to its place, purpose and policy implications. This is undertaken in the context of a study of national Scottish outdoor recreation data which itself examined the salient characteristics of Scottish outdoor recreation consumption over time using This paper reports on an analysis of time series data for outdoor recreation participation amongst Scottish adult residents between 2003 and 2007 inclusive. Notwithstanding some inevitable limitations to the data (discussed in TNS Travel and Tourism (2008)) particularly relating to some changes in the wording of questions in 2005, a number of behaviour patterns suggest that outdoor recreation, in Scotland at least, is becoming increasingly differentiated in the way it is consumed. The paper explores the nature of this differentiation and examines some of the drivers, drawn from a wider body of literature that might seek to explain it. The drivers relate to behaviour patterns underpinned by both policy instruments and a range of social, economic and environmental factors. This kind of differentiation can aid the understanding of those drivers of participation that can be influenced by targeted 2|Page policy, those that are likely to be moderated only by more general social policy, and those which fall outside of the potential of policy influence altogether. Participation in countryside recreation: long term structural decline It is now widely accepted that participation in countryside recreation 1 has been in long term structural decline in the United Kingdom as indeed it also has been in other western countries such as New Zealand (SPARC, 2008) and more recently in the United States (Roper, 2004). Broom’s (1991) assessment of United Kingdom countryside recreation participation, for example, normalising data from a number of surveys, was that it more or less halved in volume between 1984 and 1989. By 1995, the House of Commons Environment Committee (1995) concluded that there had been no growth in countryside recreation trips in Britain at all since the surveys began in 1977 and “between 1998 and 2002/03, all day trips to the (English) countryside declined by 12%” (Great Britain Day Visits Survey 2004). Between 2002/03 and the 2005 England Day Visits survey, total countryside visits had fallen by a further staggering 45% (Natural England, 2005). Whilst the reductions are nowhere as extreme in Scotland, the Scottish Recreation Surveys (ScRS) show that countryside recreation participation has declined by some 9% between 2003 and 2007 (TNS Travel and Tourism, 2008). A number of commentaries that have sought to explain this change in the British context have attributed it largely to changing lifestyles and cultures rather than any lack of material means to participate. The policy infrastructure for countryside recreation in Britain was founded on particular normative notions of ‘rural refreshment’ and physical and moral ‘improvement’ prevalent during the first half of the 20th century. These asserted the importance of countryside recreation as being to develop the potential of the individual (Blunden and Curry, 1990) “to enable us to develop to the full, our individualities” (Joad (1937), p. 65) and where “hiking (was to) has replace beer as the shortest cut out of Manchester” (Joad (1937) p.76). The countryside was to be a place “where men (sic) may be assured of solitude, of the refreshment of country sights and sounds and of the companionship of wild things” (Joad (1937) p. 82) for solitude and communion with nature (Rothman, 1982). These imperatives must be understood as part of process of industrialisation in which rural-urban and work-leisure became seen as increasingly distinct realms (Solnit, 2001). They also reflect the enduring influence of romantic notions of how the outdoors ought to be appreciated, heavily class-based This is a ‘British’ term that more globally would pertain to outdoor recreation that takes place in rural areas beyond the town. This definition is consistent with most of the countryside recreation visitor surveys conducted in the United Kingdom since the late 1970s. 1 3|Page notions emphasising the quiet contemplation of ‘scenery’ and of nature as the ‘other’ of everyday city-based society (Edensor, 2000; Suckall et al 2009). Clark et al (1994) suggest that there has been a shift away from rural refreshment towards a more commodified (Cloke and Perkins, 2002) view of outdoor recreation experiences built around personal ‘choice’. The popularity of golf and holiday village resorts are conspicuous examples of this. Many commodified activities emphasise the element of challenge (Hardy, 2003) with some commonly associated more with exhilaration than relaxation (Beedie and Hudson, 2003) and more with (perceived or actual) risk-taking than security (Lewis et al, 2007). Although it can be argued that these elements have long been features of outdoor recreation, such as mountaineering, their valorisation has extended beyond traditional, largely privileged, social groupings (Thomas, 1983). Yet the ability to convey status remains an important factor underpinning the attraction of particular venues and activities. They provide exclusivity. This is made more pronounced as different social groups express their identity in different ways through their leisure activities. As commodified outdoor recreation becomes more ‘packaged’, predictable and convenient, it can also become less space extensive. It is also argued that, in some cases, the ‘countryside’ significance can become incidental in the process of enjoyment. Under these circumstances, an activity’s original social, cultural and landscape context can be replaced by a completely different consumptive context (McNaughten and Urry 1998). Here, being in the countryside can mean very different things to different people. Research specifically in relation to children and young people suggests that they are leading increasingly urban, sedentary and technologically-led lives engendering a general disassociation with ‘the outdoors’ (Adam, 2008). Traditional forms of outdoor recreation are ‘uncool’, lack interest and excitement, and can be associated with unpleasant smells and bad weather (Countryside Agency, 2005; Henley Centre, 2005). Young people often seek to pursue forms of outdoor recreation perceived as more ‘extreme’. In terms of socio-economic position, too, those on low incomes have been found to have low expectations of visits to, different experiences of, and even a lack of awareness of the potential of, the countryside for outdoor recreation (Defra, 2008), preferring to remain local (and therefore for most, urban) in their behaviour patterns. This is supported by ScRS data too. 4|Page Whilst there is still a desire on the part of many to be close to nature, ways in which this can be experienced are becoming more diffuse, allowing a range of different opportunities in addition to simply visiting the countryside. A renewed emphasis on ‘local’ environments (local green space, local nature reserves, local footpath networks, community forests and the like – discussed further below) has displaced more distant countryside trips (Cochrane, 2008). Exposure to nature also takes more ‘detached’, consumptive and representational forms through, for example, the purchase of natural products (Kearsley, 2000) and ‘nature’ television programmes (Pigram and Jenkins, 2006). Pergams & Zaradic (2006) suggest a shift away from people's direct appreciation of nature (‘biophilia’) to 'videophilia’: a sedentary, derived appreciation. Perceived and actual changes to the rural landscape as a result of changing agricultural practices and climate change are also put forward as factors which may deter participation; for example through both the loss of certain types of habitat (Shoard, 1980; Stern, 2006) and increasingly unpredictable weather conditions (Shaw and Loomis, 2008). It has long been known that the frequency of participation in outdoor recreation reduces as distance travelled to participate increases, and that access to a car increases the propensity to participate (Pigram and Jenkns, 2006). More recently, other factors have also served to depress the propensity to travel longer distances for outdoor recreation. The relative cost of fuel has had an influence as has our increasing awareness of the environmental impacts of the use of the car (Urry, 2008). In this context, the National Travel Statistics of the Scottish Household Survey support the findings of the ScRS: the average distance travelled for holiday and day trips declined by 22% between 1995 and 2005. There also have been leisure ‘substitution’ effects where outdoor countryside activities have been replaced by indoor ones through, for example, visits to the gym, physical social activities such as dancing and indoor climbing walls (Hyder, 1999) and indoor BMX tracks (Howell, 2008). This shift again reflects trends towards commodification and diminishing time budgets compounded by the perception that they are safer and more predictable in the experiences that they offer than their outdoor equivalents. There is evidence, too, to suggest that black and minority ethnic (BME) groups are significantly under-represented in outdoor recreation, especially in the countryside (Morris, 2003; Askins, 2004; The Countryside Agency, 2005). It is sometimes suggested that BME communities reject the countryside and that outdoor recreation has limited ‘cultural’ significance or value (Milbourne, 1997). However, there is evidence for significant latent demand, but demand which is constrained by a number of barriers, 5|Page often intersecting with class-based barriers (Countryside Agency & Black Environment Network, 2003; Askins, 2004; Countryside Agency, 2005; Singh & Mazzoni, 2007). Home-based leisure activity also has displaced countryside recreation participation. The growth in home-based leisure opportunities - including home cinema, digital satellite and DVD, the MP3 player, computer and internet (Inchley et al, 2008) - has created for some people, an increase in sedentary leisure (Wachter, 1998, Sturm, 2004). It has also facilitated the vicarious enjoyment of sport and recreation: involvement increasingly based on spectating rather than participation (Hinch & Higham, 2001; Greenwood et al. 2007). In addition, increasing home ownership has led to significant increases in homebased leisure, particularly DIY (Roberts, 2004) and gardening (Bhatti and Church, 2001), moving people away from the pursuit of more distant outdoor recreation. In these contexts, the limitations of supply-based countryside recreation policies are clear (Curry and Ravenscroft, 2001). If the reasons for non-participation are not – or at least not solely - to do with a lack of material opportunity to recreate in the countryside then increasing provision (through agri environment schemes, wider public access, the provision of forest, country and other parks and so on) – which is the principal armoury of countryside agencies - will not on its own, be met with the desired increased consumption response (Curry, 2001). This is not to disregard questions concerning the precise nature and location of provision, which remain important (GreenspaceScotland, 2009; SNH, 2006). Despite this decline in the use of the countryside for outdoor recreation, the Scottish Recreation Surveys (ScRS) of the new millennium (TNS Travel and Tourism, 2004, 2007, 2008) show that outdoor recreation as a whole is increasing. This is shown, broken down by age, in figure 1 below 2. Between 2003 and 2007 the proportion of the Scottish adult population undertaking regular (more than once a week) outdoor recreation of all types rose from just under 33% to just over 44% in a gradual fashion. Evidently, this growth is taking place in locations other than the countryside (as perceived by the survey respondents), which might suggest that its characteristics also are different. This prompts a closer investigation of the nature of outdoor recreation and how it is becoming increasingly differentiated in respect of both motivations for participation and policy responses. All of these surveys are based on people’s own interpretation of the meaning of outdoor recreation. They are of the Scottish adult (16 and over) resident population only. Two surveys were conducted in 2005 (termed A and B in the figure), as part of a decision to change the format of some of the questions in the survey. TNS (2008, page 4) suggest that revisions to the questionnaire are more likely to be the cause of the time series differences within 2005, than change in behaviour patterns per se. 2 6|Page Figure 1 near here. The localisation of outdoor recreation: a busy and health-aware population The ScRS indicate that whilst outdoor recreation is on the increase in Scotland, this is as a result of an increasing localisation of recreation visits and as a result, urban spaces are becoming more popular and rural spaces less so. The types of outdoor recreation activity have not changed here (walking is still the dominant activity) it is just that the location is changing. Specific rural locations are declining in importance (again, relative to urban locations), but the destination experiencing most significant growth over time is the ‘local park’ (in both rural and urban situations). Some 37% of all outdoor recreation visits in 2007 were to the ‘local park or open space’ (25% in 2004). This suggests that it is not the popularity of the countryside per se that is diminishing relative to the town for outdoor recreation trips but, rather, that outdoor recreation is becoming more local and, because the majority of the population is urban, the town is the increasingly common setting for these localised trips. This is reinforced by data on distances travelled for outdoor recreation participation. The two shortest distance categories (less than 2 miles and between 2 and 5 miles) have increased in popularity consistently over the survey period and the three longest ones (61 – 80 miles, 81 – 100 miles and over 100 miles) have declined in popularity. Mode of transport also supports this locality thesis. The data show an increase in walking and a decline in the use of the car as a means of getting to the outdoor recreation destination over the survey period. Other modes of transport, bus, private coach, train and bicycle remained reasonably constant as a form of transport during the survey period. The fact that over 40% of all trips were made on foot in 2007 (relative to fewer than 25% in 2003) makes them quintessentially local. Correspondingly, the use of the car declined from 66% to 50% of all trips between 2003 and 2007. Progressive Partnership (2005 and 2007), in examining use of urban greenspace, also notes the increasing popularity of the use of the local outdoors in Scotland, where accessibility is considered a critical trigger to participation. Whilst dog ownership provides some obligation to undertake regular exercise it was a less important motivation in these surveys than simply walking and than playing with children. This localisation of outdoor recreation appears to have three sets of drivers. The first is that of people’s time budgets. The ScRS shows that the length of outdoor recreation 7|Page visits is getting shorter. The two shortest lengths of visit categories (less than an hour and one to two hours) have grown constantly over time, the third shortest time category (2 – 3 hours) has remained reasonably constant over the survey period and all of the longer time periods exhibit a consistent decline. In this context, it has been postulated that, as working lives have become increasingly busy, leisure time budgets have been divided into smaller ‘bytes’. Outdoor leisure consumption has become shorter, more intensive and more specialised (Hill, 2002) and, inevitably, more local. As a means of preserving time, people are increasingly choosing the most convenient leisure option available to them, looking for activities that will enable them to keep fit, have fun and look good all at the same time (Yeoman et al., 2008). In terms of outdoor recreation consumption there is also competition with other convenient options, such as the gym, particularly for urban dwellers in higher socioeconomic groups. Many non-participants in outdoor recreation, particularly young families, cite the time required to organise a trip as the main constraint to participation (Henley Centre, 2005). The exception to this general influence of time is amongst the over 65s, who are not so time constrained as a result of retirement. This lack of a time constraint amongst the over 65s is reflected in the profile of overall participation in figure 1, where this age category is one of the fastest growing categories of recreation participants in Scotland overall. Secondly, there are a number of demographic and behavioural factors influencing localisation. There is evidence, for example, that as populations become older, their outdoor recreation experiences become more local (Pigram and Jenkins, 2006) rather than reduce in amount. It is not necessarily the case that overall participation declines steeply with age. Many over 65s are less willing than previous generations to accept functional decline as a natural part of the aging process and seek medical and technological intervention in order to continue participation in active leisure for longer – a development consistent with the increase in participation of the over 65s in the Scottish surveys. However, ageing and caring responsibilities ultimately do mediate access to leisure and leisure choices (Phillipson et al., 2008). Whilst for some, too, exploring new places is part of the outdoor recreation experience, familiarity through regular use and a sense of belonging may be a stronger trigger to participation (Williams, 2002). Here, increased regularity of outdoor recreation means shorter distances, and the largest growth in outdoor recreation in the ScRS survey between 2003 and 2007 has been amongst very frequent (21 – 30 visits in the four weeks prior to the survey): as people recreate more often, individual visits become more 8|Page local. In this context, a person’s commitment to their activity can overcome any perceived limitations in environmental quality, indicating a different way of doing outdoor recreation compared to more traditional ideas of going to iconic sites to appreciate their scenic value. Thirdly, there is some evidence that general policy exhortations towards both physical and mental health are having an impact on the localisation of outdoor recreation (Pretty et al, 2005). These exhortations have grown considerably in all parts of the United Kingdom over the past 20 years: the World Health Organisation (2007), the Chief Medical Officer (Department of Health, 2004) and the English Department of Culture, Media and Sport (2002) all have slightly different recommendations around taking 30 minutes daily exercise, and other exhortations come from the reporting of the consequences of not taking regular exercise (World Health Organisation, 2006). In Scotland, National Performance Indicator (NPI) 41 is to “increase the proportion of adults making one or more visits to the outdoors per week” (Scottish Government, 2008). The ScRS between 2003 and 2007 confirm that this is being achieved. The Henley Centre’s (2005) study reports, too, that the media have increased awareness of the health benefits of physical activity, which has served to boost participation. With the emphasis on physical and mental health (the benefits are reviewed, for example, in Bischoff, 2007, Hardman & Stensel, 2003 and NHS Health Scotland 2008), the ‘small but often’ exhortation leads to more local participation: the location in which ‘exercise for health’ takes place can become subservient to the exercise itself (Parker, 2008) A further trigger in respect of health is a generally perceived threat of withdrawal of health care for the obese, stemming from general health messages which increasingly emphasise the notion of individual responsibility for wellbeing and connect it to lifestyle ‘choices’3 (Sointu, 2005). Indeed, using exercise to treat specific conditions joins a more general trend of increased interest in care and training of the body (Crossley, 2006), thought to link in part to greater body image consciousness (Bush et al., 2001). Research confirms that pet owners tend in general to be healthier and more active than the average member of the population (Wells, 2007; Mcnicholas & Collis, 2000). Dog ownership in particular generates a daily commitment to outdoor recreation. Currently 39% of people in the UK own a dog but increasingly busy lifestyles mean this figure is declining over time (falling 26% between 1985 and 2004) (Mintel, 2005; Blue Cross, 3 The notion of ‘choice’ being a contested one. 9|Page 2007; National Pet Month Survey 2008). The requirement for frequent dog walking means that it is largely conducted locally. Given the concurrence of greater participation in local outdoor recreation with the expansion of national policies providing health exhortations, it could be argued that such policies are influencing participation. More generally, however, it is probably changing lifestyles and work patterns that have influenced the growth in this type of outdoor recreation as much as any policy set. Indeed, it could be that some of the increase in local recreation constitutes displaced demand specifically from countryside recreation. Community outdoor recreation: health, physical activity and the environment Distinct from general exhortations about exercise and health, there is a range of more directive initiatives at the community level that actively seek to encourage outdoor recreation. These differ from local outdoor recreation both functionally and in policy terms. Functionally, whilst local outdoor recreation is about doing things closer to home, community outdoor recreation is driven by exhortations to do things together. In policy terms, whilst local outdoor recreation is associated with general national health exhortations, community outdoor recreation is lined with the community empowerment agenda (Rhodes, 1997, Kooiman, 2003) and the policy ‘style’ of developing a range of targeted social policies for implementation through communities themselves and the development of community action (Giddens, 1998). There are at least four types of community initiative: targeted community sports initiatives; general practitioner referral schemes; specific exercise programmes and the development of green gyms, social farms and community gardens. Whilst there is an overlap between these and activity triggered by more general health exhortations, their discrete nature lies in the development of very specific policy sets from both the public and voluntary sectors, to tackle health problems. These have come about as policy sets because of a general recognition that although exercise improves physical and mental health it does not axiomatically trigger participation since this trigger is considered often to be culturally embedded (Henderson & Ainsworth, 2001; Carlisle, 2006; Henderson & Bialeschki, 2005). There is evidence that certain demographic groups are more health conscious than others, and have different health risk profiles, for example, varying with age (Henley Centre, 2005) and 10 | P a g e social grade (Burton & Turrell, 2000)4. Health motivations to recreate are also tempered by perceived health risks of recreating in the outdoors regarding disease, personal safety and negotiating traffic (Milligan & Bingley, 2007). Somewhat paradoxically, ill-health has been identified as a key barrier to participation in outdoor recreation (Social and Community Planning Research, 1999), which is especially pertinent for the Scottish population with its comparatively poor physical and mental health (ScotPHO Health and Wellbeing Profiles, 2008). In the ScRS, however, this factor has declined as a principal barrier to participation. In 2006 it accounted for 33% of all principal reasons for nonparticipation and 2007 it had reduced to 28% of all principal reasons. Directly in response to the identification of hard to reach groups there were significant changes, from the late 1990s, in the way community sport was to be funded and delivered. This reflected a Government recognition of the importance of sport in communities as well as elite competition, particularly for health purposes, but also to act as a ‘feedstock’ for elite sport (Baker and Owens, 2008). This was to be undertaken through a number of policy agencies working in concert at a local scale (Department of Health, 2002, Department of Culture, Media and Sport, 2002), such as local authorities and primary and secondary health care authorities. Key performance indicators for such community sport, as well as participation, included volunteering, club memberships and coaching, reinforcing the ‘community’ basis of such schemes (Baker and Owens, 2008). From 2004, the UK-wide Community Sport Initiative was introduced, with different schemes for each of the Home countries (for England, Game Plan (Department of Culture, Media and Sport, 2004) and Choosing Activity (Department of Health, 2005), for Wales, Mentro Allan (Sports Council for Wales, 2008), and a number of different sources of funding including the Big Lottery. In Scotland, the Active Futures Programme aims to make sport more widely available to all, particularly ‘hard to reach groups’ such as women, disabled people, black and minority ethnic (BME) communities, rural communities and those disadvantaged by social and economic deprivation. It has the added purpose of seeking to identify talented sportspeople. Somewhat at variance with NPI 41, the strategy is working towards an overarching goal for 60% of Scots to take part in sport at least once a week by 2020 (Big Lottery Fund, 2009). Examples of Active Futures projects relating to outdoor recreation include the Scottish Ethnic Minority Sports Association, the Women’s Active Pathways Project (SWAPP) and Burton & Turrell (2000) found that those in blue-collar occupations were around 50% more likely than white collar occupations to be classified as insufficiently active for health in a way that was not explained by hours worked. These are crucial issues for Scotland, where it is recognised that social inclusion issues substantially influence health (Scottish Government, 2008). 4 11 | P a g e ‘Groups in Boots’. SWAPP aims to increase physical activity amongst 17-25 year old women from BME groups (Hall-Aitken, 2006b). Specific objectives include identifying and addressing the barriers to participation, such as inadequate service provision, marriage, religion, career choices. A major barrier they seek to overcome is the perceptions of parents who often have fears about safety and racism and do not understand the benefits of sport and physical activity. ‘Groups in Boots’ offers a walking activity programme for young people with mental health issues in East Lothian (HallAitken, 2006b). The aim is to encourage them to take part in a ‘mainstream’ physical activity, which in time gives them the confidence and social skills to join a ‘mainstream’ walking group or even become ‘peer leaders’. The project is led by Stepping Out who have run similar programmes for all ages since 1993 but who found that young people were not taking part in their activities. Many of these schemes currently are being evaluated, but some commentators have questioned their long term effectiveness in respect of influencing healthy lifestyles (Hilsdon et al, 2005) because of a lack of motivation and commitment on the part of participants. This perhaps reinforces the significance of behavioural changes being fully culturally embedded in participants social worlds. In addition, the multi-agency and multi-funding framework for the schemes makes complex both their resourcing and policy sets. More specific still than the Community Sport Initiative in seeking to target hard to reach groups generally, are health referral schemes. Physical Activity Referral Schemes (PARS) have been increasingly used in the United Kingdom since the early 1990s to rehabilitate those with both physical and mental health problems (Crone et al, 2008). Such schemes also have a preventative purpose (Gidlow et al, 2005) and are thought to be the most common example of community-based activity programmes (Crone et al, 2004). These schemes involve referral by a health practitioner (usually a General Practitioner) to a leisure provider who tailors a supervised activity programme. More recently, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2006) has recommended that these be largely suspended, however, due to a lack of evidence of their effectiveness (Gidlow et al, 2007). A third community approach focuses on the development of walking groups, designed to increase public awareness of how health improvements can motivate people to participate more in outdoor recreation. The Walking the Way to Health Initiative, for example, was introduced during the late 1990s in England (Natural England, 2007), with a similar programme, ‘Paths to Health’, started in Scotland in 2001, specifically to 12 | P a g e promote local exercise, amongst the more sedentary (Paths to Health, 2006).. In Scotland the charity ‘Paths for All’, comprised of 20 partnership organisations including SNH, the NHS and a range of other public and third sector bodies, has taken forward the twin agendas of promoting health walks and developing the extent and quality multi-use path networks, particularly around local communities. Their work is considered a key delivery mechanism for Scotland’s Physical Activity Strategy (Scottish Executive, 2003). A number of drug rehabilitation schemes in Scotland, too, have used active countryside recreation instrumentally (Curry et al, 2001). Some UK metropolitan areas also have developed ‘health walk’ schemes. Several cities have produced CDs with health walk maps as well as the designation of particular routes on the ground. Again, these have tended to be ‘doorstep’ schemes rather than exhortations for visits to the more distant countryside. Natural England and the Department of Health are also working together on the National Step-O-Meter Programme (NSP) which is a 'Choosing Health' White Paper project. It aims to make pedometer use accessible, affordable and effective in clinical practice, particularly to sedentary, 'at risk' or 'hard to reach' groups (Jarrett et al, 2004). Driven from this policy stance there is a clear (if perhaps incidental) thrust to making outdoor recreation more local as this is seen to be the type that is most likely to induce participation amongst more sedentary groups. At present there has been insufficient evaluation of such health walking schemes to be able to judge their effectiveness in stimulating and extending outdoor recreation participation, particularly in the longer term. The National Evaluation of health walk schemes across England and Scotland (WHI, 2006) found positive outcomes in terms of encouraging and sustaining participation but did not investigate beyond a 12 month period. In terms of social diversity, they did find that participation was largely made up of older, white, female and more affluent members of the population. In the case of Scotland, evaluation of the Paths to Health programme has tended to focus on outputs rather than outcomes and more detailed studies are partial in geographical coverage and are not structured for easy comparison. What can be reported is that at the end of the first five years of the programme there were 190 walking groups across Scotland involving 12,706 walkers (Paths to Health, 2006). Regional studies such as that undertaken in the Cairngorms National Park have shown that the vast majority of participants were previously inactive (Paths to Health, 2007). Finally in respect of community outdoor recreation, the Scottish Executive (2007) champions the value of environmental work for health and fitness as well as for building 13 | P a g e community capital. This builds on work by the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers, and other conservation bodies in developing the notion of the ‘green gym’, where conservation work is also exercise: improve both your health and the environment at the same time. Research by Oxford Brookes University (2008) found such green gyms to be socially inclusive, to make a positive contribution to physical and mental health, to increase confidence and skills levels and to be a useful referral destination for health professionals: as well, of course, as improving the environment (Pretty et al, 2005). Natural England too has introduced a ‘Green Exercise’ programme to encourage physical activity and improve mental health. This represents a move away from the ‘quiet enjoyment of the countryside’ as a backcloth to exercise, explicitly focusing on using and shaping local and urban areas in ways that help to target non-traditional participants in outdoor recreation and deprived areas. Despite the importance of the environment declining as the primary object of outdoor recreation (i.e. the shifting emphasis away from ‘special’ or iconic areas) its importance as a context has been asserted. Bird (2004), for example, argues that the availability of greenspace, biodiversity and other ‘pleasant’ environments does actually encourage increased participation in physical activity by increasing the motivation to do it. Beck (2003) suggests that access to aesthetically pleasing environments has a positive bearing on our mental well being. A growing number of studies link health and wellbeing (including spiritual and psycho-social rather than simply biological health) specifically to engagements with the outdoors5 (e.g. Lea, 2008; Mass et al. 2006; Land Use Consultants, 2004; Hartig et al. 2003; Ulrich, 1991). There is some evidence to suggest that contact with nature can help prevent ill health as well as helping us to recover from it. A greater role has also been identified for physical and nature-based activity as a recognised treatment for mental illness, lessening reliance on drug-based treatments, as has happened for physical disorders such as heart disease (Faulkner & Biddle, 2001; Motl et al. 2000). The specific influence of community outdoor recreation initiatives on overall outdoor recreation participation in Scotland is difficult to isolate with any accuracy because these activities are diffuse across the surveys. The ScRS, too, questions only the adult population and therefore no information is available about younger people. In respect of community sports, however, despite a range of policy exhortations, the impact on this type of outdoor recreation consumption, in Scotland at least, might be slight. Sportscotland (2008) data on trends suggest that running/jogging amongst the adult Scottish population, for example, declined slightly (from 6% in 1994-1996 to 4% in 5 often referred to as green and open spaces, therapeutic landscapes or green infrastructure. 14 | P a g e 2005-2007), although this was more marked amongst children (from 28% to 11% for the same periods). Both Sportscotland (2008) and the ScRS conclude that running/jogging amongst the adult population has remained constant between 2003 and 2007, however. Data on ‘activity’ club memberships (TNS, 2008) suggest that such participation is buoyant, but involves only a small proportion of the Scottish population and coheres around team sports. Membership of activity clubs amongst children of school age declines from the final primary school year, particularly amongst girls (Inchley et al, 2008). There is no conclusive empirical evidence either, about the direct and active use of the environment for outdoor education, although Edwards et al (2008) suggest that the active use of woodland in Scotland for learning activities, interpretation and schoolbased education, is significant. The Forestry Commission (2005) suggests that the majority of this activity is local to home. Efforts have been made to encourage healthier lifestyles using a community-based approach, such as the ‘Have a Heart Paisley’ project (introduced in 2000). By 2004, the evaluation of the project (Blamey et al, 2004) revealed that measurable improvements over a 3-yr period were limited to greater consumption of fruit and vegetables amongst older and wealthier residents: The impact in respect of increases in outdoor exercise was negligible, even though some residents took part in exercise programmes. Overall, despite the greatest effort of public policy for outdoor recreation being focussed on this range of community initiatives, there is as yet insufficient evidence – or at least insufficient or piecemeal evaluation – to validate or otherwise their effectiveness, ether as ends in themselves or as transitional activities that lead to different kinds of exercise. In many cases, initiatives attempt to tackle one of the toughest challenges: turning nonparticipants into regular participants. Market-based outdoor recreation: commodification and difference For Scotland, all of the categories in the ScRS surveys that have a clear market orientation – either in terms of costs of entry or the need for capital equipment (such as water sports, mountain biking and horse riding) - show reasonably constant levels of consumption over the years of the survey. Sportscotland (2008) time series data too, over a longer time period from 1994 to 2007, show a clear constancy in participation rates over time for a range of ‘capital intensive’ sports (canoeing, sailing, horse riding, wind surfing snowboarding, skiing) although participation rates are low in all of these 15 | P a g e (less than 5% of both the adult and ‘child’ population). Cycling activity is both more popular (around 10% of the adult population and 40% of the child population) and more volatile by year, although still with no longer term trend upwards or downwards. The passing of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 might be expected to boost participation in a number of these capital-intensive and market-related activities. The broad scope of the legislation in providing for access to most land and inland water for all forms of non-motorised mobility presents clear potential for growth in participation in a greater diversity of recreational activities beyond the most established practices, particularly for so-called ‘adventure’ activities that are often more costly, such as mountain biking, kayaking and rafting. The fact that the provisions of the Act extend to commercial activities ought to give further impetus to such growth and diversification. However, the legislation came into force in February 2005 and it is therefore difficult to assess the impact of the legislation with the data currently available (i.e. up to 2007). In time a clearer picture will emerge of the extent to which enhanced legal legitimacy has influenced diversified and commercial forms of outdoor recreation. It is known from a scoping study of the impacts of land reform policy (Slee et al. 2008) and from an ongoing study of recreation and access in Cairngorms National Park (Brown et al. 2008; Brown, 2009a, 2009b) that a change in access law does not necessarily lead quickly or straightforwardly to a change in recreational practices due to the complexity and dynamics of established cultural norms. What has been identified, however, is an enhanced confidence in taking access - particularly for ‘newer’ or more commodified forms of recreational activity - due to the clarification of entitlements and responsibilities enshrined in the Act. This could, in time, lead to a growth in the volume, regularity or extent of these activities. Of course related market-based consumption patterns will be broadly influenced by economic as well as cultural factors and economic cycles undoubtedly impact on discretionary expenditure. People are more likely to cut back on large expenditures such as holidays abroad and indulge in more modest holiday and leisure activities. Thomas Cook has reported that 1 in 4 British holidaymakers who took package deals in 2007 would not do so in 2009 and two leading travel agents were to reduce their summer holiday capacity by 20-27% between 2009 and 2010 (Bowers, 2008). Less foreign travel may enhance consumption on the domestic market. Economic cycles, however, may be more volatile than participation per se because some participation can take place using capital equipment already purchased and is therefore 16 | P a g e not expenditure dependent at point of use. ‘Dedication’ to particular activities, too, can lead to participation being relatively price and income inelastic (Siegfried and Zimbalist, 2000). More casual market based outdoor recreation (for example that associated with tourism) is likely to be more volatile in line with the fluctuations of the economy. As was noted in the first section of this paper, market-based outdoor recreation in general has grown, too, through the commodification of outdoor recreation experiences into ‘bounded’ goods and their subsequent commercialisation (Roberts, 2004, Rojek, 2005, Bramham, et al, 1995). This has been associated with a growth in disposable incomes and the increased ‘status’ associated with participation in particular activities (Clark et al., 1994). In response to this demand, providers have moved to ‘brand’ the recreation experience, often in relation to aspects of nature, wildness, adventure, action, risk and ‘extreme’ sports (Bennett et al 2003). Activity, nature and adventure tourism are expanding niche markets both in Scotland and beyond (Kane & Tucker, 2004; Greenwood & Yeoman, 2007). Some suggest that such commodification may significantly alter the cultural and social values surrounding the valorisation of nature (Macnaughten and Urry, 1998). This could affect the recreational practices associated with such values and, in tandem with a diversified range of uses and users vying for the same recreational space, pose additional challenges for policy makers and managers responsible for managing access and recreation. As this commodification develops, as is argued by Macnaughten and Urry (1998), the cultural and social values surrounding the valorisation of nature, are significantly altered. This can affect the practices associated with them, including those underpinning outdoor recreation activity. However, The the operation of related commodified markets is mediated by a whole range of se commodified markets also have their own ebbs and flows in consumption as a result of cultural factors, which shape the ebb and flow of rates and styles of participation. Elements of subcultures, communities of interest or ‘neo-tribes’ (Kiewa, 2002), which develop their own values, appearance, language and the like as part of performing distinct identities (O’Conner and Brown, 2007), are often particularly subject attractive to forces agents of commodification. The broad cultural currency and innovative, fast-evolving nature of ‘adventure’ sport in particular provides substantial scope for commercial opportunity. The impetus to develop new markets encourages the development and diversification of ‘cult’ sports (e.g. kite surfing, base jumping) particularly in terms of new skills, equipment and experiences. This leads to markets for outdoor recreation becoming more fragmented (Mintel, 2005). 17 | P a g e However, there appears to be contestation and a creative tension between the ‘everyday’ practice, innovation and evolution of many subcultural recreation activities and their becoming commodified (Rinehart & Sydnor, 2003). M The broad cultural currency and innovative, fast-evolving nature of ‘adventure’ sport in particular provides substantial scope for commercial opportunity. The impetus to develop new markets encourages the development and diversification of ‘cult’ sports (e.g. kite surfing, base jumping) particularly in terms of new skills, equipment and experiences. This leads to markets for outdoor recreation becoming more fragmented (Mintel, 2005). However, m any elite or committed practitioners are not comfortable with what they sometimes see as the sanitisation, disembodiment or ‘selling out’ of their activity. Selling an image (e.g. through clothing or magazines) or objects (e.g. equipment) can become as much a focus as the action itself, and experiences of perceiving risk or danger are sold whilst creating sometimes perverse relationships with objective risk (Bridgers, 2003). Instead practitioners often prefer to emphasise the skill, corporeal and sensual practice, sociability and immersion in ‘place’ of the activity (ibid; Wheaton, 2000, 2004). For professional athletes the need to attract sponsorship can compromise their ability to resist such developments. Furthermore, the widening appeal and commercialisation of activities once considered ‘extreme’ can compromise their ‘alternative’ status (Yeoman et al., 2008) diminishing their appeal for early adopters (Schwier, 2008). An understanding of the appeal of different recreational activities – and how their practice, evolution and commercialisation is variously resisted - can aid policymakers seeking to increase participation whilst minimising conflicts within popular recreational areas. Conclusions: a taxonomy and some prospects Data from Scottish surveys cannot fully segregate the four types of outdoor recreation considered in this paper, nor indeed are they mutually exclusive. These data, however, do allow different types of outdoor recreation to be distinguished. Countryside recreation is still the largest element of outdoor recreation but is in decline. Active communitybased outdoor activity, from the analysis presented here, appears to be relatively constant over time in Scotland as does the ‘sporting’ element of commercial outdoor recreation. Both of these outdoor recreation segments remain small. Other aspects of commercial leisure, such as tourism, are likely to fluctuate more in line with the state of the economy. The largest area of growth (and indeed the only observed area of growth from Scottish data) in outdoor recreation, given that it is increasing overall in Scotland, lies in the casual, regular outing that takes place close to home. Examination of the drivers of change in outdoor recreation suggest that shifts in lifestyles and work patterns 18 | P a g e have influenced the growth in this type of outdoor recreation as much as policy, with much of the increase likely to have been directly displaced from specifically countryside recreation. What is important about this differentiation is that it allows the identification of different motivations and drivers to participation for different types of outdoor recreation, which is important for policy information if policy seeks to influence participation. It also allows the analysis of policy itself to the extent that different policy sets are addressing different types of outdoor recreation. In this context, countryside recreation policy is seen to have a limited impact on levels of countryside recreation participation because policy is almost entirely supply-side orientated: it predominantly influences only what is provided (quality and amount) when outdoor recreation participation is largely related to culture, lifestyle and how this intersection with socio-economic opportunities and constraints, and not supply per se. Localised outdoor recreation participation may be influenced by general national polices relating to lifestyle and health: regular exercise and healthy eating. Here, the media is also likely to have significant influence on behaviour. Nevertheless the cultural embeddedness of health-enhancing objectives and practices appears to be the crucial factor in long-term behavioural change towards health-enhancing objectives and practices. Indeed, the data suggest that the positive response in respect of participation is skewed towards the higher social grades and therefore such national lifestyle policies do not successfully address equity considerations. To redress this, a series of more local direct policy interventions has been introduced in the form of GP referral schemes and exercise programmes specifically targeting sedentary groups, as well as voluntary organisation campaigns to get local communities actively working for the environment. Thus far, however, there is insufficient evidence, to determine whether this policy approach directed at community outdoor recreation is having any significant lasting long-term impact. Finally, whilst market-based outdoor recreation participation appears to have remained reasonably constant in Scotland in the new millennium, this has taken place outside of any particularly directive policy interventions. As part of the research reported here, a focus group was held with Scottish outdoor recreation experts to reflect on the evidence and come to a view about the prospects of outdoor recreation consumption over the next 20 years. In the context of an overall gradual growth in outdoor recreation participation over this period, localised outdoor 19 | P a g e recreation was considered to be the area of principal growth, driven by health imperatives, limits to the availability of time and carbon reduction practices. It would remain local and fragmented largely because of increasingly complex personal time budgets and declining real incomes. This kind of recreation was likely to become more ‘jointly’ consumed with functional walking or cycling to the shops, or increasing localised food production, for example, where the environmental context would change from a more traditional association with ‘amenity’. In the longer term, the increasing unpredictability of the weather is likely to further ‘localise’ outdoor recreation. Growth here would be only slow, however. Countryside recreation is likely to continue to decline overall because of money and time constraints, but visits to ‘honey pot’ destinations and ‘enthusiast’ pursuits may well remain popular, if perhaps undertaken less frequently. It was felt by the expert group that community outdoor recreation might grow over the next 20 years because of the general move to strengthen communities and an increasing awareness of the environment and the need for local food production. The growth is therefore more likely to come from the ‘green gym’ movement than health referral schemes. Such growth as does take place is likely to be more widely spread across social grades than the growth in localised outdoor recreation. It was felt that market-based outdoor recreation would fluctuate over the next 20 years largely in response to changes in the state of the economy, transport system and disposable incomes. These insights highlight the need to understand latent - as well as expressed – demand for outdoor recreation and the complexity of converting it to actual participation, particularly in addressing issues of social inclusion. Ensuring the provision of sufficient and appropriate recreational opportunities and facilities for people of all ages, backgrounds and abilities is vital but must be matched with policy implementation that encourages the active and regular use of these facilities by a wide range of people. It is therefore crucial that the tendency for policy to neglect the role played by cultural and socio-economic factors in producing outdoor recreation participation must be addressed. Acknowledgement This research was conducted with a grant from Scottish Natural Heritage. The views contained here, however, do not necessarily represent the views of SNH, and any errors or omissions remain the responsibility of the authors and not the funding body. References 20 | P a g e Adam, D. (2008). Wilderness under threat as visitors stay indoors. The Guardian, 5th February 2008. Askins, K. (2004). Visible communities’ use and perceptions of the North York Moors and Peak District National Park. A policy guidance document for National Park Authorities. September. Baker, C M and Owens, C S (2008) Participation in Sport and Active Recreation in Gloucestershire: a summary. Gloucester: University of Gloucestershire. Beck, S. (2003). Environmental Justice in Scotland. How does the Healthy Environment Network interpret this concept and what is happening in Scotland to address environmental injustice? A Report for the Healthy Environment Network Web publication: http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/4074henenvjustice101103.pdf Beedie, P. & Hudson, S. (2003). Emergence of mountain-based adventure tourism, Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 625-643. Bennett, G., Henson, R. K., & Zhang, J. (2003). "Generation Y's perceptions of the action sports industry segment", Journal of Sport Management, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 95-115. Bhatti, M. & Church, A. (2001). Cultivating natures: homes and gardens in late modernity, Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 365-383. Blunden J and Curry N R (1990) (eds) A People's Charter?: 40 Years of the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. Big Lottery Fund (2009) the Community Sport initiative in Scotland BTCV Green Gym National Evaluation Report: Summary of Findings, BCTV, Doncaster Bird, W (2004). Can green space and biodiversity increase levels of physical activity? Report to the RSPB. Web publication: http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/natural_fit_full_version_tcm9-133055.pdf Bischoff, A. (2007). "Phenomenological perspectives on outdoor recreation/activity, nature and quality of life", European Journal of Public Health, vol. 17, p. 43. Blamey, A., Ayana, M., Lawson, L., Mackinnon, J., Paterson, I., Judge, K. (2004). The independent evaluation of ‘have a heart paisley’. Public Health and Policy Unit, University of Glasgow. Web publication: http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/4014-HaHP1-final-eval.pdf Blue Cross (2007). Annual Review, http://www.bluecross.org.uk/web/FILES/Literature/Annual_Review_2007.pdf Bowers, S. (2008). Holiday firms prepare for package tour slump by slashing capacity, The Guardian, 3rd December 2008. Bramham P, Cricher C and Tomlinson A (1995). the Sociology of Leisure, E and F N Spon, London 21 | P a g e Bridgers, L. 2003. Out of the Gene Pool and into the Food Chain. In Rinehart, R.E. & Sydnor, S. (eds.) To the Extreme: Alternative Sports Inside and Out, State University of New York Press, Albany, 179-189. Broom G., 1991. Pricing the countryside: the context. Countryside Recreation Research Advisory Group Annual Conference Report, Our priceless countryside, should it be priced? University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, Manchester, 25– 27 September. Brown, K.M., Marshall, K. & Dilley, R. (2008) Claiming rights to rural space through offroad cycling, Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Association of American Geographers April, 2008, Boston. Brown, K.M. (2009a) ‘Just because I can take my bike there doesn’t mean I should’: Some key tensions in outdoor recreation citizenship, Paper presented at RGS-IBG Annual Geographers Meeting, 26-28 August 2009, Manchester. Brown, K.M. (2009b) The role of culture in exercising access rights, Paper presented at Rural Law - Land Reform in Scotland: 10 years of a Scottish Parliament, 3 September 2009, Aberdeen. Burton, N. W. & Turrell, G. (2000). "Occupation, hours worked, and leisure-time physical activity", Preventive Medicine, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 673-681. Bush, H. M., Williams, R. G. A., Lean, M. E. J. & Anderson, A. S. (2001). Body image and weight consciousness among South Asian, Italian and general population women in Britain, Appetite, 37(3), 207-215. Carlisle, S. (2006). Thinking About ‘Culture’ as an Influence on Health and Wellbeing, Cultural Influences on Health & Wellbeing in Scotland Study, Discussion Paper 3: April 2006 Clark, G., Darrell, J., Grove-White, R., Macnaghten, P. & Urry, J. (1994). Leisure landscapes, Council for the Protection of Rural England, London Cloke, P., & Perkins, H. C. (2002). Commodification and adventure in New Zealand tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 5(6), 521-549. Cochrane P C (2008) Community Involvement in Woodlands: Governance and Social Benefits, unpublished PhD thesis, College of Humanities and Social Science, University of Edinburgh Countryside Agency (2005). “What About us?” Diversity review evidence – part one. Challenging perceptions: under represented groups’ visitor needs. Research notes CNR 94. Crone D., Johnston LH., Gidlow C, Henley C and James DVB (2008) Uptake and participation in physical activity referral schemes in the UK: an investigation of patients referred with mental health problems Issues in Mental Health Nursing 29:1088–1097. Crone, D., Johnston, LH., & Grant, T. (2004). Maintaining quality in exercise referral schemes: A case study of professional practice. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 5(5), 96–103. Crossley, N. (2006). In the gym: Motives, meaning and moral careers, Body & Society, 12(3), 23-50. 22 | P a g e Curry N. R., (2001) Access for Outdoor Recreation in England and Wales: Production, Consumption and Markets, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 9 (5), 400 – 416. Curry N R, Joseph D and Slee RW (2001) To climb a mountain? Social inclusion and outdoor recreation in Britain. World Leisure, 3, pp 3 – 15. Curry N R and Ravenscroft N (2001) Countryside Recreation Provision in England: Exploring a Demand-led Approach, Land Use Policy, 18 (3), 281 – 291. Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2002). Game Plan: A Strategy for Delivering Government’s Sport and Physical Activity Objectives. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport Strategy Unit. Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2008). Outdoors for all?: An action plan to increase the number of people from under-represented groups who access the natural environment. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Department of Health (2004). At Least 5 a Week Evidence on the Impact of Physical Activity and its Relationship to Health. London: The Stationary Office. Department of Health (2004b). Choosing Health: Making Healthier Choices Easier. London: The Stationary Office. Department of Health (2005). Choosing Activity: A Physical Activity Action Plan. London: Department of Health. Edensor, T. 2000. Walking in the British countryside: reflexivity, embodied practices and ways to escape. Body & Society, 6(3-4), 81-106. Edwards, E., Morris, J., O’Brien, L., Srajevs, V. & Valatin, G. (2008). The economic and social contribution of forestry for people in Scotland. Forestry Commission Scotland. Web publication: http://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/pdf/fcrn102.pdf/$FILE/fcrn102.pdf Faulkner, G. & Biddle, S. (2001). "Exercise and mental health: It's just not psychology!", Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 433-444. Forestry Commission (2005). Forestry visitor surveys. Web publication: http://www.forestry.gov.uk/pdf/VisitorSurveysummaryreport2005_NG.pdf/$FILE/Visitor Surveysummaryreport2005_NG.pdf Giddens A (1998) The third way: the renewal of social democracy, Polity Press, Cambridge. Gidlow, C., Johnston, L. H., Crone, D.,&James, D. V. B. (2005). Attendance of exercise referral schemes in the UK: A systematic review. Health Education Journal, 64(2), 168– 186. Gidlow C, Johnston LH, Crone D, Morris C, Smith A, Foster C, James DVB (2007) Sociodemographic patterning of referral, uptake and attendance in Physical Activity Referral Schemes, Journal of Public Health, p1 – 7. Great Britain Day Visits Survey (2004), Survey for 2002-03, TNS Travel and Tourism, Edinburgh, GreenspaceScotland (2009) Making the links: Greenspace for a more successful, sustainable Scotland, http://www.greenspacescotland.org.uk/upload/File/part%201%20%20making%20the%20links.pdf 23 | P a g e Greenwood, C., Yeoman, I. & Campbell, E. (2007), From bugging to sphereing: The prospects for Scotland’s adventure tourism product, Tomorrow’s world: Consumer and tourist, 3(1), May 2007. Hall-Aitken, (2006a) SEMSA Womens Active Pathways Project (SWAPP) , http://www.bigcsi.com/casestudies/SWAPP.pdf (Hall-Aitken, 2006b) Groups in Boots, http://www.bigcsi.com/casestudies/Groups%20in%20Boots.pdf Hardman A E, Stensel DJ (2003) Physical activity and health. the evidence explained. Routledge, London Hardy, D. (2003). The rationalisation of the irrational: Conflicts between rock climbing culture and dominant value systems in society. In B. Humberstone, H. Brown & K. Richards (eds.) Whose journeys? The outdoors and adventure as social and cultural phenomena. Barrow-In-Furness, The Institute of Outdoor Learning, 173-186. Hartig, T. et al. (2003). Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psych., 23, 109-123. Henderson, K. A. & Ainsworth, B. E. (2001), "Researching leisure and physical activity with women of color: Issues and emerging questions", Leisure Sciences, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 21-34. Henderson, K. A. & Bialeschki, M. D. (2005). "Leisure and active lifestyles: Research reflections", Leisure Sciences, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 355-365. Henley Centre (2005). Drivers of change in outdoor recreation. A report for Natural England. Web publication: http://www.countryside.gov.uk/LAR/Recreation/strategy_background.asp Hill J (2002). sport, leisure and culture in 20th century Britain, Plagrave, London Hillsdon, M., Foster, C. and Thorogood, M. (2005). Interventions for promoting physical activity. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Issue 1. Article No. CD003180.pub2. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003180.pub2. Available at: http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003180/frame.html. Hinch, T.D. & Higham, J.E.S. (2001). Sports tourism: A framework for research, International Journal of Tourism Research, 3(1), 45-58. House of Commons Environment Committee (1995). The impact of leisure activities on the environment. HC 246 – I. HMSO. London. Howell, O. (2008). Skatepark as neoliberal playground: Urban governance, recreation space, and the cultivation of personal responsibility, Space and Culture 11. Hyder, M.A. (1999). Have your students climbing the walls: The growth of indoor climbing, The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 70(Nov). Inchley, J., Kirby, J. & Currie, C. (2008). Physical activity amongst adolescents in Scotland. Final report to the physical activity in Scottish schoolchildren (PASS) study. Jarrett, H., Peters, D. & Robinson, P. (2004) Evaluating the 2003 Step-o-meter loan pack trial. Report to the British Heart Foundation and the Countryside Agency. 24 | P a g e Joad, C.E.M. ((1937)) The people's claim. Britain and the Beast p. 67. — in: C.W. Ellis (Ed.); (London: J.M. Dent and Sons) Kane, M.J. & Tucker, H. (2004). Adventure tourism: The freedom to play with reality. Tourist Studies, 4(3), 217-234 Kearsley, G. (2000). Balancing tourism and wilderness qualities in New Zealand’s native forests. In X. Font, & J. Tribe, (eds.) Forest Tourism and Recreation: Case Studies in Environmental Management, Wallingford, CABI, 75-91. Kiewa, J. (2002). Traditional climbing: Metaphor of resistance or metanarrative of oppression. Leisure Studies, 21(2), 145-161. Kooiman J (2003) Governing as Governance, Sage, London. Land Use Consultants (2004). Making the links: Greenspace and quality of life. technical report, Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No.060 (ROAME No.F03AB01) Lea, J. (2008). "Retreating to Nature: Rethinking 'Therapeutic Landscapes'.", Area, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 90-98. Lewis, N., Dollman, J., & Dale, M. (2007). "Trends in physical activity behaviours and attitudes among South Australian youth between 1985 and 2004", Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 418-427. Macnaghten, P. & Urry, J. (1998). Contested Natures, Sage, London Maas, J., Verheij, R. A, Groenewegen, P. P, de Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P. (2006). Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation?. Journal of. Epidemiology. Community Health 60: 587-592 Mcnicholas J. & Collis G. M. (2000). Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: Robustness of the effect, British Journal of Psychology, 91, p.61. Milligan, C. & Bingley, A. (2007). "Restorative Places or Scary Spaces? The Impact of Woodland on the Mental Well-Being of Young Adults.", Health and Place, vol. 13, pp. 799-811. Mintel (2005). Extreme sports – UK. market research report. Mintel International Group Ltd. London. Morris, N (2003). Black and minority ethnic groups and public open space. Literature Review. July. http://www.openspace.eca.ac.uk/pdf/blackminoritylitrev.pdf Motl, R. W., Berger, B. G., & Leuschen, P. S. (2000). "The role of enjoyment in the exercise-mood relationship", International Journal of Sport Psychology, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 347-363. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006) Four Commonly Used Methods to Increase Physical Activity: Brief Interventions in Primary Care, Exercise Referral Schemes, Pedometers and Community-Based Exercise Programmes for Walking and Cycling. Public Health Intervention Guidance no. 2. London: NICE. National Pet Month Survey (2008) http://www.dogmagazine.net/archives/519/uk-petowners-statistics-revealed/ 25 | P a g e Natural England (2005) England Leisure Visits Survey, 2005, NE, Cheltenham Natural England (2007) Walking the way to health initiative. http://www.countryside.gov.uk/LAR/Recreation/WHI/index.asp NHS Health Scotland (2008). Scottish Physical Activity Research Collaboration (SPARColl)., NHS Health Scotland. O’Connor, J.P. and Brown, T.D. (2007). Real cyclists don’t race: Informal affiliations of the weekend warrior. International Review of the Sociology of Sport, 42(1), 83-97. Parker G (2008) Countryside Access and the ‘Right to Roam’ under New Labour: nothing to CRoW about? In Woods M (ed) New Labour’s Countryside: rural policy in Britain since 1997, Policy Press, Bristol. Paths to Health (2006) 5th Annual Progress Report: 1 September 2005 – 31 August 2006, August 2006, Paths to Health, Inverness Paths to Health (2007) Audit of Health Walks in and Around the Cairngorms National Park and Options for Future Delivery, March 2007, Paths to Health, Inverness. Pergams, O. R. W. & Zaradic, P. A. (2006), "Is love of nature in the US becoming love of electronic media? 16-year downtrend in national park visits explained by watching movies, playing video games, internet use, and oil prices", Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 387-393. Phillipson, C., Leach, R., Money, A. & Biggs, S. (2008). Social and cultural constructions of aging: the case of the baby boomers. Sociological Research Online, 13(3). Pigram, J.J. & Jenkins, J.M. (2006). Outdoor Recreation Management, Routledge, London. Pretty, J., Griffin, M., Peacock, J., Hine, R., Sellens, M. & South, N. (2005). A countryside for health and well being: the physical and mental health benefits of green exercise. A report to the Countryside Recreation Network, February. Progressive Partnerships (2005). Greenspace Scotland omnibus survey – key findings report. Progressive Partnerships (2007). Greenspace Scotland omnibus survey – final report. Rhodes R AW (1997) Understanding governance: policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Open University Press, Maidenhead. Rinehart, R.E. & Sydnor, S. (2003). To the extreme: Alternative sports inside and out, State University of New York Press, New York. Roberts K (2004). the leisure industries, Palgrave Macmillan, London, June ISBN: 978-14039-0412-6 Rojek, C. (1995). Decentring leisure: Rethinking leisure theory, London, Sage. Roper ASW (2005) Outdoor Recreation in America 2003: Recreation’s Benefits to Society Challenged by Trends, The Recreation Roundtable, 1225 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC, January. 26 | P a g e Rothman B (1982) 1932 Kinder Trespass: A Personal View of the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass, Willow Publishing, Altrincham, April Schmidt, C. & Little, D. (2007). Qualitative insights into leisure as a spiritual experience. Leisure Studies, 39(2), 222-247. Schwier, J. (2008). Commitment, identity and subcultural media in alternative sport, Zeitschrift fur Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 28(3), 271-282. ScotPHO (2008). Health and Wellbeing Profiles 2008 - Scotland Overview Report, http://www.scotpho.org.uk/nmsruntime/saveasdialog.asp?lID=4461&sID=3822 Scottish Executive (2003) Let's Make Scotland More Active: A strategy for physical activity, Physical Activity Task Force, http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/47032/0017726.pdf Scottish Executive (2007) www.cosla.gov.uk/attachments/aboutcosla/concordatnov07.pdf Scottish Government (2008). Equally well: Report of the Ministerial Task Force on Health Inequalities, Edinburgh. Shaw, W. D. & Loomis, J. B. (2008). "Frameworks for analyzing the economic effects of climate change on outdoor recreation", Climate Research, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 259-269. Social and Community Planning Research (1999). United Kingdom Leisure Day visits Survey 1998. Social and Community Planning Research, London. Siegfried J and Zimbalist A (2000) The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities , Journal of Economic Perspectives,14 (3), pp. 95-114 Slee, B., Brown, K.M., Blackstock, K.L., Dilley, R., Cook, P., Grieve, J. & Moxey, A. (2008) Monitoring and Evaluating the Effects of Land Reform on Rural Scotland: a Scoping Study and Impact Assessment, Report for Scottish Government Social Research. SNH (2006) Greenspace for Communities: Policy Review, Scottish Natural Heritage, http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/wwo/sharinggoodpractice/greenspaceforcommunities.pdf Sointu, E. (2005). The rise of an ideal: tracing changing discourses of wellbeing, Sociological Review, 53(2), 255-274. Solnit, R. (2001) Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Verso, London. SPARC (Sport and Recreation New Zealand) 2008. Outdoor Recreation Review: Initial Findings Report, July 2008, http://www.sparc.org.nz/research-policy/policy/key-policyprojects Sportscotland (2008). Sports participation in Scotland 2007. Research digest no. 108. Sportscotland, Edinburgh. Stern, H. (2006). The Economics of Climate Change: the Stern Review, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Sturm, R. (2004). "The economics of physical activity - societal trends and rationales for interventions", American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 126-135. 27 | P a g e Suckall, N., Fraser, E.D.G., Cooper, T. & Quinn, C. 2009. Visitor perceptions of rural landscapes: A case study in the Peak District National Park, England. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 1195-1203. Thomas K (1983) Man and the natural world: changing attitudes in England, 1500 – 1800, Allen Lane, London. TNS Travel and Tourism (2004). Great Britain day visits survey 2002-03, Edinburgh. TNS Travel and Tourism (2007). Scottish Recreation Survey: annual summary report 2006, Scottish Natural Heritage, 295 and 321 (ROAME No. F02AA614/5). TNS Travel and Tourism (2008). Scottish recreation survey: Annual summary report 2006. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 295 (ROAME No. F02AA614/5). Ulrich, R. et al. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology., 11. 201-230. Urry, J. (2008). 'Climate change, travel and complex futures', British Journal of Sociology 59(2): 261-279. Wachter, C. J. (1998). "Exploring VCR use as a leisure activity", Leisure Sciences, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 213-227. WHI (2006) Walking the Way to Health Initiative 2000-2005: National Evaluation of Health Walk Schemes, http://www.whi.org.uk/uploads/documents/2335/NatEvalresearchnote.pdf Wells, D.L. (2007). Domestic dogs and human health: an overview. British Journal of Health Psychology 12, 145-156. Wheaton, B. (2000). “Just do it.” Consumption, commitment and identity in windsurfing subculture. Sociology of Sport Journal, 17(3), 254-274. Wheaton, B. (2004). Introduction: mapping the lifestyle sport-scape, in Wheaton, B. (ed.) Understanding lifestyle sports: consumption, identity and difference, London, Routledge, 1-28. Williams, D. R. (2002) Leisure identities, globalization, and the politics of place. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(2), 351-367. World Health Organisation (2007). A European Framework to Promote Physical Activity for Health. Denmark: WHO regional office for Europe. World Health Organisation (2006). Physical Activity and Health in Europe Evidence for Action. Denmark: WHO regional office for Europe. Yeoman, I., McPherson, G. & Black, L. (2008) What will the sports tourist look like in 2014? Tomorrow’s world: Consumer and tourist, 3(5), April 2008. 28 | P a g e Proofing Points Mine Page 37, line 5, for ‘lined’ read ‘linked’ Page 38, line 48, for ‘as’, read ‘to be’ 1. Shoard M (1980) Milbourne P (1997) Countryside Agency & Black Environment Network, (2003). Capturing Richness. Countryside visits by black and ethnic minority communities, Countryside Agency, Cheltenham. Singh, J. & Mazzoni, S. (2007) Building inclusive environments. Report for Lancashire Youth and Community Service and the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), Lancashire County Council, Preston. Sports Council for Wales (2008) – Mentro Allen report 2. 3. 4. This is fine 5. 6. 7. 8. Publisher and place Countryside Agency (2005). “What About us?” Diversity review evidence – part one. Challenging perceptions: under represented groups’ visitor needs. Research notes CNR 94, the Agency, Cheltenham. Jarrett, H., Peters, D. & Robinson, P. (2004) Evaluating the 2003 Step-o-meter loan pack trial. Report to the British Heart Foundation and the Countryside Agency. Land Use Consultants (2004). Making the links: Greenspace and quality of life. technical report, Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No.060 (ROAME No.F03AB01), SNH, Battleby, Perth. 9. 10. 11. 12. 29 | P a g e 13. 30 | P a g e Figure 1 - Overall ‘regular’ (at least one activity in the previous week) outdoor recreation participation in Scotland over time, by age. 55 50 45 40 % 35 30 25 20 2003 2004 2005A 2005B 2006 2007 Years 16 - 24 25 - 44 45 - 64 65+ 31 | P a g e