Rhetoric is persuasion

advertisement

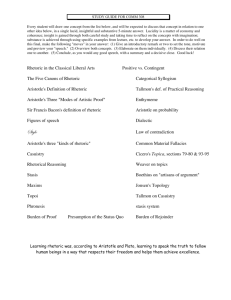

Derek Emerson MAJ Garriott ERH 201WX 28 NOV 2015 Rhetoric as the Techne of Persuasion In today’s society, the amount of information, media, content, and opinions we are exposed to is staggering. This makes it possible for the views and opinions of vast amounts of people to be heard by audiences the world over. With that being said, you often hear from commentators and pundits who have criticism for figures in society that something is just “rhetoric’ or “empty rhetoric”. What does that imply? This statement is heard so often in regards to speech and written word of figures in our society, and isn’t limited strictly to politicians. These pundits and commentators are essentially making the connotation that rhetoric or “empty rhetoric” is a bad thing. Due to this the possibility that our society has lost sight of what rhetoric is, is very real. What Rhetoric actually is, is highly debatable. The best definition that I can ascertain is that it is broadly the techne of persuasion. I say broadly because it can include imagery, oration, speeches, and written forms. Some scholars such as Carole Blair disagree by citing Aristotle’s work. This paper will contend with her argument as well as others and give evidence to support the original claim that Rhetoric is the techne of persuasion. Rhetoric encompasses persuasion in all its forms but this shouldn’t be frowned upon like the critics do. It merely needs to be recognized as rhetoric, from there the informed audience members can make their own decisions as to whether they will be persuaded or not. By doing this, the public at large and citizens of our society can make sense of the vast amounts of content and information aforementioned. To make this argument I will present information in chronological order, starting with early rhetoricians and philosophers such as Gorgias and moving through to prominent ideas presented by intellectuals from the Middle Ages. Considering the sophist Gorgias is believed to have been born around 385 B.C.E, it is logical for us to start out argument with him. Gorgias was arguably a founder of the sophistic movement and a well-known rhetor. He was most well known for his work such as the Encomium of Helen in which he defends Helens betrayal, with his position that she was heavily persuaded. Gorgias says this of speech and the influence on Helen “ For the speech which persuades the soul constrains the soul which it persuades both to obey its utterances and to approve its doings”. (Cite here page 81 of encomium). Gorgias is indirectly referring to the power of persuasion that is inherent in spoken rhetoric. In Gorgias’ time as a sophist and rhetor he also heavily explored the idea of logos in his oration. Aristotle later identifies logos as being verbal persuasion, which becomes one of his famously known rhetorical appeals. (Herrick Cite here) If logos (verbal persuasion) is a critical rhetorical appeal, than that means our argument is already partly proven. (Introduce Carole Blaire and Andrea Lunsford). As important as Gorgias is to Rhetoric and its history, Plato may have been more important towards the end of what we think of Rhetoric today. Plato was thought to have been born sometime around 423 B.C.E (Herrick Cite here). Plato’s opinions on rhetoric varied throughout his career as a philosopher. We can’t fault him for this, as new information becomes available or new perspectives are found, opinions can be swayed. We can reference two of Plato’s works where the departure in ideas are evident. Plato’s Gorgias and later his Phaedrus offer us two of his original thoughts on the matter. In Gorgias he develops an imaginary dialogue between Gorgias and Socrates, in which they debate the realm and use of rhetoric. While Plato makes the point that rhetoric is not a true art in the Gorgias he reverses his position in the Phaedrus. In Gorgias he does point through dialogue between Gorgias and Socrates that he believes the chief end of rhetoric is first and foremost; persuasion. This is evident in the following quote from the perspective of Gorgias in the dialogue “ What is greater than the word that persuades the judges in the courts, or the senators in the council, or the citizens in the assembly, or at any other political meeting? If you have the power of uttering this word, you will have the physician your slave, and the trainer your slave, and the money-maker of whom you talk will be found to gather treasures, not for himself, but for who you are able to speak and persuade the multitude”. (Classics MIT) In the dialogue Socrates goes on to question the true natures of rhetoric if it persuasion. He agrees that rhetoric is persuasion but contends that it is not an art and can never allow for true justice, which is beside the point of the argument we are trying to prove. Again he later reverses his stance on the position of rhetoric as a techne. In the dialogue Gorgias immediately drives the point home in a reply to Socrates by saying this “No: the definition seems to me very fair, Socrates; for persuasion is the chief end of rhetoric”. Sometime later Plato reverses his original stance in his Phaedrus on rhetoric and realizes that Rhetoric does have a place, and is a techne with the audience being God himself. We already know that Plato believes that Rhetoric is persuasion, now it is time to display where the techne of rhetoric becomes a possibility in the mind of Plato. In Phaedrus, another imaginary dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus, Plato details that spoken rhetoric, not written rhetoric, is a true art. This can be seen in the following quote “ Go and tell Lysias that to the fountain and school of the Nymphs we went down and were bidden by them to convey a message to him and other composers of speeches-to homer and other writers of poems, whether set to music or not; and to Solon and others who have composed writings in the form of political discourses which they would term lawsto all of them we are to say that if their compositions are based on knowledge of the truth, and they can defend or prove them when they are put to the test, by spoken arguments, which leave their writings poor in comparison of them, then they are to be called not only poets, orators, legislators, but are worthy of a higher name, befitting the serious pursuit of their life”. (Cite here, MIT) Plato uses this quote from the perspective of Socrates, talking to Phaedrus. You notice his admission that spoken rhetoric and those who use it are to be taken seriously and is an art form. Plato never uses the word techne within the Phaedrus but does gives the same effect with this quote. Plato was very important to the advancement of rhetoric in ancient Greece, and his pupils would go on to further advance rhetoric in their lifetimes with one in particular standing out: Aristotle. While Aristotles ideas on rhetoric aren’t entirely pertinent to this argument, he does have a slight departure from his mentor on the realm and definition of rhetoric. In Aristotle’s Rhetoric he details that rhetoric is the ability to see the ability to be persuasive and how to carry out persuasion in all situations (Cite here Stanford.edu on Aristotle) Aristotles views on rhetoric and its persuasive characteristics ended up transcending generations and finding its way into the minds of philosophers and educators hundreds of years later. One in particular was Quintilian, responsible for the writing of De Institutio Oratoria and was an educator who spanned multiple empirical rules and was the personal instructor of Julius Caesars children. (Herrick Cite here) Andrew Bourelle, a PhD Student out of Nevada University, Reno had his essay on Quintilians rhetorical views published in the Currents, a peer reviewed journal published twice annually out of Worcester State University. Bourelle had this to say on Quintilian: “Rhetoric, to Quintilian, was not simply the art of persuasion and certainly was not thought of in a pejorative sense as the term is often used today in politics or the news media. Murphy (1986) says, “Rhetoric, or the theory of effective communications, is for Quintilian merely the tool of the broadly educated citizen who is capable of analysis, reflection, and then powerful action in public affairs” (Cite here Worcester). This is important because even though Bourelle identifies that Quinitllian doesn’t necessarily believe rhetoric is persuasion in reference to his De Institutio Oratoria he makes concessions as to what Quintilian means. Bourelle says that rhetoric is a tool used by those with gifts of “analysis, reflection, and then powerful action in public affairs”. If you remove all the colorful language and words and boil what down what Bourelle is saying then you can see he aligns Quintilian views with Aristotles view that rhetoric is the ability to see persuasion in all circumstances. Is that not what Bourelle is saying in relation to Quintilian? The analysis and reflection gives the same effect as seeing opportunity for persuasion as Aristotle would. So if Quintilian’s and Aristotle’s definitions of Rhetoric are not far removed from eachother, and Aristotle and Plato’s definitions are not far from each other, then our argument is beginning to hold water with so many important figures backing it. Obviously the definition is going to shift and evolve with passing time, as new ideas and perspectives are discovered. However the basic framework of the definition of rhetoric matches our thesis thus far in the historical analysis. The last figure we will examine is St. Augustine….. (go from here and give conclusion)