the-romantic-era-20052006-1221761253531226

advertisement

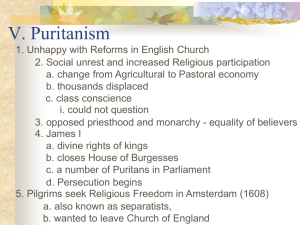

Introducing the Romantic Era:1798-1832 A Multimedia Presentation by Dr. Christopher Swann La Belle Dame Sans Merci, John William Waterhouse (1893) Liberty Leading the People, Eugène Delacroix (1830) Instructions: Day 1 For the next two days, you will be learning about the literary periods leading up to the British Romantic Era (1798-1832). The two topics that these lessons will focus on are the Seventeenth Century and the Enlightenment. You will be working individually on the assignments. Dr. Swann will be available to assist you if you run into problems with the program. These lessons are designed to be easy to follow and move around in. In order to move to the next slide, click on the mouse button (for Macs) or the left mouse button (for PCs). To move backwards, click on the Right mouse button and choose “Previous” (for PCs) Instructions: Day 1 (continued) Occasionally you will come to a slide that contains a hyperlink. A hyperlink will take you out onto the Internet, show you a picture or a poem, lead you to a sound file, or do other neat things when you click on it. If you get out on the Net and get lost or run into problems, ask Dr. Swann or Mrs. Temple for help. If you look at the bottom of the screen when out on the Internet, you will see a narrow strip of this presentation. To switch back to the lessons from the Internet, simply click on the part that you see, or click on the “Back” button at the top of the Internet menu. Other directions will be given to you at the appropriate times. Remember to pace yourself so that you will cover all the material, but don’t rush to the end. Have fun! Instructions: Day 1 (continued) Spaced throughout the slides will be questions in boxes for you to answer. When you come to one (they will be clearly marked), follow the following procedure: Click the RIGHT mouse button. Choose MEETING MINDER. Type in the number of the question you are answering and your answer. You can move the Meeting Minder box around the screen if you need to see the presentation. Click “OK” after each answer. Question #1: Did you understand the directions above? If so, type your name for your first answer. English Civil War (1642-1660) After Queen Elizabeth I’s reign (1558-1603), religious and political grievances which had lain more or less hidden under the surface came to life. Under Elizabeth, the Anglican Church—created by Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII—held to the middle of the road between Catholicism and Protestantism. Puritans, a sect of Protestantism, worshiped and even held positions of authority within the Anglican Church in the time of Elizabeth. When Elizabeth died and James I became king in 1603, this situation changed; James I did not conceal his hostility of Puritans and, as head of the Anglican Church, began dismissing Puritan clergyman. James I’s son, Charles I, was even worse in the eyes of the Puritans, not least for marrying the daughter of the king of France, a Catholic. As most of the English were Protestants, this fact alone alarmed much of the nation. Charles’ attitude and behavior did not help the situation—he demanded strict conformity from Puritan clergy, extorted loans from his subjects to finance unpopular wars, and generally seemed determined to be, in the words of Charles Dickens, “to be a high and mighty king not to be called to account by anybody.” Portrait of Charles I, Anthony van Dyck (c. 1635) English Civil War (1642-1660) Continued Eventually arresting Parliament leaders who protested against his policies, Charles further alienated the Puritans as his archbishop, Laud, brutally and publicly persecuted Puritans, even mutilating their faces. This lead Puritans to question the entire concept of the “divine right” of Charles’ rule and to make the following revolutionary statement: “A King is a thing men have made for their own sakes.” Such a statement suggests that if a king can be made, then a king can also be unmade, an idea that both infuriated and terrified Charles. In 1642, Parliament condemned Charles as a tyrant, and when Charles sent armed men into Parliament to seize opposition leaders, the leaders escaped, Parliament raised its own army, and Charles fled north with his loyalists, setting off civil war. Oliver Cromwell, 1650 The king’s supporters, known as Cavaliers because they were largely skilled horsemen or cavalry, fought against the Puritan’s New Model Army, led by Oliver Cromwell. In 1645, Cromwell defeated and captured Charles I. Meanwhile, the most radical Puritans took control of Parliament, shut out more moderate members, and on January 1, 1649, beheaded Charles I and declared England’s monarchy abolished. English Civil War (1642-1660) Continued The English Commonwealth became the new government of England, replacing the monarchy, and was led by Oliver Cromwell. However, the execution of Charles I led to a decline in popularity for the Puritans, whose severe policies outlawing gambling, newspapers, and theater exacerbated the situation. Cromwell had to rule as a virtual dictator until his death in 1658. As a result of public anger at Puritan policies, Parliament reconvened and asked Charles II, the son of Charles I, to become king, which Charles did in 1660, restoring the monarchy. Question #2: Name two examples (one each) of how both Charles I and the Puritans acted in ways that created tension and made conditions in England worse. Warring Poets: Metaphysics vs. Cavaliers Cavalier Poets Metaphysical Poets John Donne George Herbert Andrew Marvell Robert Herrick Richard Lovelace Metaphysical Poetry: •Characterized by an unusual degree of intellectualism •Often draws on material from fields not typically associated with poetry, such as law, natural science, metallurgy, medicine, etc. •Employs conceits, unusual and surprising comparisons between two things that would never be normally associated with one another •Often employs paradoxes, figures of speech which are apparent contradictions that reveal a kind of truth Cavalier Poetry: •Usually does not reflect turbulent times of the age but focuses instead on love, beauty, honor, and time •Often light, whimsical, and polished verse—usually written as songs John Donne (1572?-1631) • • • • Raised Roman Catholic, originally an active courtier; composed fine love poems Eventually became Anglican (Protestant) minister and turned to religious poetry Master of metaphysical conceits and paradoxes Read Donne’s “Holy Sonnet 14” (“Batter my heart, three-personed God…”) and then answer questions “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” —from “Meditation 17” by John Donne “Holy Sonnet 14” Batter my heart, three-personed God; for You As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend; That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new. I, like an usurped town, to another due, 5 Labor to admit You, but O, to no end; Reason, Your viceroy in me, me should defend, But is captived, and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly I love You, and would be loved fain, But am betrothed unto Your enemy. 10 Divorce me, untie or break that knot again; Take me to You, imprison me, for I, Except You enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me. three-personed God: the Trinity viceroy: Deputy enthrall: Enslave Question #3: What are the paradoxes in lines 3, 13, and 14? George Herbert (1593-1633) Easter Wings Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store, Though foolishly he lost the same, Decaying more and more, Till he became 5 Most poore: With thee O let me rise As larks, harmoniously, And sing this day thy victories: 10 Then shall the fall further the flight in me. My tender age in sorrow did beginne And still with sicknesses and shame. Thou didst so punish sinne, That I became 15 Most thinne. With thee Let me combine, And feel thy victorie: For, if I imp my wing on thine, 20 Affliction shall advance the flight in me. store: abundance • • • • • imp: graft Original Text: George Herbert, The Temple. Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations (Cambridge: by Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel, printers to the University, 1633): 34-35. First Publication Date: 1633. Representative Poetry On-line: Editor, I. Lancashire; Publisher, Web Development Group, Inf. Tech. Services, Univ. of Toronto Lib. Edition: RPO 1999. © I. Lancashire, Dept. of English (Univ. of Toronto), and Univ. of Toronto Press 1999. Born to wealthy aristocratic family; favorite of King James I Family friend of John Donne Chose to become country parson at remote rural church in 1630; served poor parishioners until his death in 1630 Poems only published after his death in his collection, The Temple, which became enormously popular Emblem poem: poem that is shaped to serve as a picture, motto, and explanation of the poem’s content Question #4: Why is this poem in the shape it is in? (What does the shape have to do with the content?) Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) • • • • Son of Puritan minister, wrote poetry in Greek and Latin Tutor to ward of Oliver Cromwell; later unofficial court poet of Cromwell Sponsored by John Milton (see Puritans) Poetry more relaxed than Herbert’s or Donne’s Read “To His Coy Mistress” online to answer the following question. Question #5: Summarize in a sentence the central ideas found in each of the following three parts of the poem: lines 1-20, lines 2132, and lines 33-46. Warring Poets: Metaphysics vs. Cavaliers Cavalier Poets Metaphysical Poets John Donne George Herbert Andrew Marvell Robert Herrick Richard Lovelace Metaphysical Poetry: •Characterized by an unusual degree of intellectualism •Often draws on material from fields not typically associated with poetry, such as law, natural science, metallurgy, medicine, etc. •Employs conceits, unusual and surprising comparisons between two things that would never be normally associated with one another •Often employs paradoxes, figures of speech which are apparent contradictions that reveal a kind of truth Cavalier Poetry: •Usually does not reflect turbulent times of the age but focuses instead on love, beauty, honor, and time •Often light, whimsical, and polished verse—usually written as songs Robert Herrick (1591-1674) • • • • • • Known as greatest songwriter in English language Poetry is light, whimsical, and joyful to read Born to wealthy goldsmith, graduated from Cambridge; ordained a minister, served as chaplain with British troops fighting in France Eventually became country parson in southwest England, where he wrote his verse Evicted from parish by Puritans after Charles I’s defeat; returned to native London and published poetry, which was widely unread in his lifetime Returned to parish after Restoration of 1660, where he remained until his death Click here to read “Delight in Disorder” Click here to read “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” Question #6: Herrick’s poetry often exhibits an attitude of carpe diem (“seize the day”). How do both of the above poems do this? Richard Lovelace (1618-1657) • • • • • “Pretty boy” of Cavalier poetry—so handsome that king and queen ordered that he earn his master’s degree from Oxford before he completed his studies From extremely wealthy family; quite talented— playwright, painter, played musical instruments Chosen by Royalists to demand from Parliament a restoration of king’s absolute right to authority; immediately arrested—wrote poetry while imprisoned Released from prison and rejoined Charles’ forces After Charles’ defeat in 1645, Lovelace went to France and fought against Holland; returned to England some time later, imprisoned again by Puritans—where he wrote “To Lucasta”—and, it is believed, died in poverty Click here to read “To Lucasta” in order to answer the following question. Question #7: How does the speaker attempt to justify the fact that he is leaving Lucasta? End of Day 1 Instructions BEFORE you finish today: 1. Right click the mouse and choose Meeting Minder again. 2. Choose “Export.” 3. Choose “Export Now.” 4. The program will send your answers to Word. 5. In Word, choose print. 6. BEFORE exiting the program, get your paper and check it over. 7. When you are satisfied with your answers, turn them in and exit Word and Power Point. Instructions: Day 2 Welcome to your second lesson. On Day 1, you learned about the English Civil War of the 17th century and the Metaphysical and Cavalier poets. Today you will learn about the great Puritan poet John Milton, the Restoration period, the Enlightenment of the 18th century, the Neoclassical ideal, and the Pre-Romantic writers. Again, pace yourselves and do not hesitate to ask for help if you need it or have questions. Instructions: Day 2 (continued) Spaced throughout the slides will be questions in boxes for you to answer. When you come to one (they will be clearly marked), follow the following procedure: Click the RIGHT mouse button. Choose MEETING MINDER. Type in the number of the question you are answering and your answer. You can move the Meeting Minder box around the screen if you need to see the presentation. Click “OK” after each answer. Question #8: Did you understand the directions above? If so, type your name for your first answer. Puritan Poet: John Milton (1608-1674) • • • • • • Ranked with Shakespeare and Chaucer as one of the greatest poets in the English language Born in London into middle-class Protestant family; mastered Greek, Latin, Hebrew and many modern European languages before going to college Spent years before Civil War reading everything written in all the languages he knew; determined to become a great poet Joined Puritan side in Civil War, wrote pamphlets in defense of republican principles of Puritans—Cromwell made him Latin Secretary of the Commonwealth Went blind, then imprisoned during Restoration—later released In blindness and poverty he wrote Paradise Lost, the greatest epic in the English language, about the fall of Adam and Eve and Satan’s role in that fall—he earned only ten pounds for his masterpiece! From Paradise Lost, Book I “Is this the region, this the soil, the clime,” Said then the lost Arch-Angel, “this the seat That we must change for Heav'n, this mournful gloom For that celestial light? Be it so, since he Who now is Sovereign can dispose and bid 5 What shall be right: farthest from him is best Whom reason hath equaled, force hath made supreme Above his equals. Farewell happy fields, Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrors! Hail Infernal world! and thou, profoundest Hell 10 Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings A mind not to be changed by Place or Time. The mind is its own place, and in it self Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven. What matter where, if I be still the same, 15 And what I should be, all but less then he Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least We shall be free; the Almighty hath not built Here for his envy, will not drive us hence: Here we may reign secure, and in my choice 20 To reign is worth ambition though in Hell: Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. But wherefore let we then our faithful friends, The associates and copartners of our loss Lie thus astonished on the oblivious pool, 25 And call them not to share with us their part In this unhappy mansion, or once more With rallied arms to try what may be yet Regained in Heaven, or what more lost in Hell?” Click here for more online information about John Milton’s life and work. Here Satan, “the lost Arch-Angel” (line 2), expresses his despair at losing heaven, but he also resolves to glory in his lost condition, saying it is “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven” (22). Satan’s great sin was pride and his refusal to serve God, which led to his expulsion from heaven. He is speaking to Beelzebub, his lieutenant, about finding themselves and their fellow rebel angels in Hell after God expelled them. Question #9: What other examples of Satan’s pride can you find in this excerpt? Question #10: What does Satan mean when he says “The mind is its own place”? Do you agree or disagree? Explain. The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century (1660-1798) The British monarchy was restored to power in 1660 when Charles II, the exiled son of the beheaded Charles I, was invited by Parliament to take the throne after years of the Puritan-run Commonwealth. Unfortunately, the reign of Charles II was hardly a tranquil one. A plague swept London in 1665, killing over 70,000 people. Only one year later, the Great Fire of London destroyed over half of the city’s houses. Religious and political problems continued to plague England as well. Charles II, who had lived in Paris during his exile, reveled in elegance and wore rich clothes and jewelry, in contrast to the drab mode of dress and behavior adopted by the Puritans. Perhaps worse from the Puritan point of view, Charles II was also Catholic, and when he died, his brother James, a stubborn man and a devout Catholic, became King James II. As king, James II alienated Puritans by giving Catholics powerful governmental positions and dismissing Parliament when it did not agree with him, recalling the turbulent reign of Charles I before the Civil War! King Charles II Click here for online information on the Great Fire of London (1666). The Restoration (continued) In 1688, James II’s wife gave birth to a son, signaling another future Catholic king of England. As a result, Parliament leaders invited Mary, the Protestant daughter of James II, to take the throne. The invitation also included Mary’s Dutch husband, William of Orange, a champion of Protestantism, to rule jointly with Mary. When William and Mary arrived in England, James II fled to France, and thus the English called this a “Glorious Revolution” as there had been no violence whatsoever. William and Mary, perhaps in gratitude for Parliament’s essentially giving them the throne, agreed to a Bill of Rights passed by Parliament. This Bill of Rights established England as a limited or constitutional monarchy, preventing a king from suspending the law and giving Parliament the right to approve all taxes. While still a monarchy, England was now among the most democratic nations of Europe. After William and Mary’s deaths, Mary’s sister Anne, a Protestant, became queen. During her reign, the Act of Union in 1707 joined the realms of England and Scotland, resulting in the nation of Great Britain with a central government in London. King William III (formerly William of Orange) Queen Mary died childless at age 32 of smallpox. Despite a succession of 18 pregnancies, Queen Anne died childless like her elder sister Mary The Restoration (continued) George I (1714-27) was magnificently unsuited to rule England. He spoke not a word of English, and his slow, pedantic nature did not sit well with the English.* George III (17601820) could at least speak the language, but he was troubled by periods of insanity that rendered him unfit to rule.* *Information taken from Britain Express website at <britainexpress.com/History/George_I.htm> and <britainexpress.com/History/George_III.htm>, accessed 29 January 2002. Question #11: How did the English government fundamentally change during this time period? During Queen Anne’s reign, England found itself once again at war with France. This war helped to polarize two political parties in Parliament. The Tories included aristocrats and lesser landowners, and were largely conservative and against change and the war. The Whigs wanted Britain to crush France once and for all and was largely made up of middleclass merchants and businessmen. In 1713, the year Queen Anne fell ill, she signed a treaty ending the war. Prior to this, Parliament had passed a law that only a Protestant could inherit the throne. When Anne died in 1714, a little-known relative of James I, George of Hanover, became king. George I spoke no English and relied on ministers from Parliament to run the country. These ministers became known as the cabinet, and the chief minister known as the prime minister, an arrangement which continues today. In 1760, another Hanoverian, George III, became king, though this George was born in Britain and considered himself English, not German. George III is best remembered for his disastrous handling of the American colonies, which led to the American Revolution. Today, the house of Hanover still rules the throne of England in the person of Queen Elizabeth II. However, it is now called the House of Windsor—anti-German sentiment during World War I led the monarchs to change the family name. The Enlightenment and the Neoclassical Ideal Quotes from the Era Titles are shadows, crowns are empty things, The good of subjects is the end of kings. —Daniel Defoe, The True-Born Englishman Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body. —Richard Steele, The Tatler To err is human, to forgive divine. —Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism Proper words in proper places, make the true definition of style. —Jonathan Swift, “Letter to a Young Clergyman” In 1660 in Britain, most people were farmers who rented land from landlords or cultivated small patches of common land. One hundred years later, farming had changed drastically with technological developments and larger farms which produced much more food with fewer workers. Those surplus workers migrated to towns to look for jobs, which spurred the Industrial Revolution. Inventions such as the steam engine made the production of manufactured goods skyrocket, which led to greater numbers of merchants shipping such English goods as cotton cloth around the world, which led to vast sums of wealth for merchants and factory owners. There was also a Scientific Revolution taking place which, above all, emphasized rationalism and logical thought and sought through scientific investigation to explain phenomena in all fields of human activity and in the natural world. Sir Isaac Newton published his study of gravity and the movement of planets in 1687. Adam Smith claimed in The Wealth of Nations that economic systems were ruled by laws as discoverable as scientific laws. John Locke, a British philosopher and political theorist, argued that a monarch’s power came from the will of the people, not by divine right. Enlightenment and Neoclassical Idea (cont’) Enlightenment thinkers saw order and harmony as the foundation of the world, and they found in the writings of classical ancient Greeks and Romans the same qualities. Because such thinkers emulated these classical styles of harmony, restraint, and clarity, they are often called neoclassical. Such authors make frequent allusions to classical mythology. They also tend to speak in generalities about the world rather than focus on particulars. Such neoclassical writers as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift were fond of satire, a form which ridicules the vanities, vices, and follies of society. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Society placed a high premium upon order and stability, which was maintained by focusing on the aristocracy as the proper social leaders. Elegance and refinement can be seen in neoclassical verse, art, music, and architecture. Nature was seen as wild and dangerous and needed to be tamed by scientific rationalization. If you’ve ever seen a boxwood garden maze or the palace of Versailles in France, or heard the music of Bach and Mozart, these are physical and auditory manifestations of the Enlightenment’s fetish for order and structure. The growing wealth of the Industrial Age led to more people getting an education and, hence, to higher levels of literacy. Coffeehouses, like modern-day Starbucks, proliferated and became the meeting places for middle-class men to meet and discuss politics, literature and newspapers, which were also spreading. Click here to listen to a Mozart minuet (an Enlightenment-era dance tune), “Minuet in F” Jean-Honoré Fragonard (17321806), A Young Girl Reading Enlightenment Literature Three Literary Ages: Age of Dryden Age of Pope and Swift Age of Johnson John Dryden (1631-1700) Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) Alexander Pope (1688-1744) Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) Age of Dryden John Dryden (1631-1700) • dominated Restoration period with poems, plays and essays; named poet laureate by Charles II • mock-heroic poetry (MacFlecknoe, 1682) often ridiculed real live people of era • All For Love best tragedy of period—often seen as remake of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Quotes from Dryden Errors, like straws, upon the surface flow; He who would search for pearls must dive below. (from All for Love) [Shakespeare] was the man who of all modern, and perhaps ancient poets, had the largest and most comprehensive soul…Wit, and language, and humor also in some measure, we had before him; but something of art was wanting to the drama till he came. (from An Essay of Dramatic Poesy) As from the power of sacred lays The spheres began to move. And sung the great Creator’s praise To all the blessed above; So when the last and dreadful hour This crumbling pageant shall devour, The trumpet shall be heard on high, The dead shall live, the living die, And Music shall untune the sky. (Grand Chorus from “A Song for St.Cecilia’s Day”) Age of Pope and Swift Daniel Defoe (1660-1731): often considered England’s first novelist best known for his book Robinson Crusoe (1719), often called first novel in English—click here to preview Robinson Crusoe sold as nonfiction—a “true account” of a man marooned on a desert isle Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders (1722) established the genre of modern novel Jonathan Swift (1667-1745): perhaps greatest satirist in English language author of Gulliver’s Travels (1726)—children’s story, fantasy, parody of travel books, political satire click here to read A Modest Proposal (1729) a satire championing Irish independence Alexander Pope (1688-1744): premier poet of his era The Rape of the Lock (1712) seen as best mock-epic poem in English—makes epic tragedy out of a baron’s cutting off a lock of hair from a lady (based on a true story) An Essay on Man (1733-34) examines human nature, society, and morals (read first stanza of Epistle II) Question #12: In Epistle II of An Essay on Man, Alexander Pope writes that man stands on “an isthmus of a middle state” and describes the middle state in great detail. In one word, what is at one end of the isthmus? In one word, what is at the other end? Age of Johnson Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) quintessential man of letters for his era read Hamlet at the age of eight; feared that insanity would deprive him of his one advantage—his intellect compiled first Dictionary of the English Language (1755)—included word histories published and edited collection of Shakespeare’s works, biographies on poets, newspaper articles, etc. subject of James Boswell’s biography Life of Johnson, seen as the finest biography in English Quotes from Johnson It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage, or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause, and diligence without reward. from Preface to A Dictionary of the English Language The end of writing is to instruct; the end of poetry is to instruct by pleasing. from Preface to the Plays of William Shakespeare Genius, whatever it is, is like fire in the flint, only to be produced by collision with a proper subject. from The Rambler #25 No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money. [On second marriages]: The triumph of hope over experience. Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully. When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford. from James Boswell’s Life of Johnson Pre-Romantic Writers The Age of Reason was in full swing by the 1750s. Factories were producing more goods for Britain than ever before. While this meant economic prosperity for thousands, it also meant horrible working conditions for thousands more as men, women, and even children toiled in filthy factories for up to fourteen hours a day. Because of these conditions, writers and intellectuals began questioning whether human reason alone could solve every problem. The Age of Reason, it seemed, had not created utopia. Writers began turning away from the high-flown style of the neoclassicists and instead used common, everyday language. These were the precursors to the Romantic era, writers who challenged Enlightenment ideals and modes. Mary Wollstonecraft, the ‘hyena in petticoats’ and radical feminist A Vindication of the Rights of Woman Thomas Gray, poet “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” Robert Burns, Scotland’s national bard “My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose” and “To a Mouse” Thomas Gray (1716-1771) From Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard Thomas Gray was a scholar and a country hermit whose most famous poem, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” actually caused a fierce and unusual struggle between Gray and a dishonest publisher. The publisher, who had found a copy of “Elegy,” wanted to print the poem. Gray, in fact, did not want it published and finally got the copy back. When “Elegy” was eventually published, Gray refused to accept payment. This poem has some of the attributes of neoclassical verse, yet it contains some of the ideals of the coming Romantic era, like its focus on the common man. Question #13: In the excerpt to the right, the “them” in line 21 refers to a certain group of dead people. Throughout this excerpt, how does the speaker characterize this particular group of dead people—who is he talking about, and how do you know? (line 25) glebe: soil (line 33) heraldry: noble descent (line 39) vault: church ceiling (line 41) urn: funeral urn; animated: life-like (line 43) provoke: call forth For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn, Or busy housewife ply her evening care: No children run to lisp their sire's return, Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share. 25 Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield, Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke; How jocund did they drive their team afield! How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke! Let not Ambition mock their useful toil, 30 Their homely joys, and destiny obscure; Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile The short and simple annals of the poor. The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r, And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave, 35 Awaits alike th' inevitable hour. The paths of glory lead but to the grave. Nor you, ye proud, impute to these the fault, If Mem'ry o'er their tomb no trophies raise, Where thro' the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault 40 The pealing anthem swells the note of praise. Can storied urn or animated bust Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath? Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust, Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death? Robert Burns (1759-1796) Known as “the voice of Scotland,” Robert Burns was a poor farmer who, despite never having a formal education, read the Bible, Shakespeare, and Alexander Pope on his own, and learned from his illiterate mother Scottish folk songs, legends, and proverbs. His poetry shows a familiarity with classical poets and an appreciation for Scotland’s culture and “voice” or particular dialect of English. The poems are honest and seem natural and spontaneous, yet they are also lyric poems full of melody. Click here to hear Burns’ “To a Mouse” read aloud in Scottish dialect. Click here to read Burns’ “My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose.” Question #14: Name at least six different ways that the speaker of “My Luve is Like a Red, Red Rose” describes his love, and quote them. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) Reviled in her day as a 'hyena in petticoats', Mary Wollstonecraft is now recognized as one of the mothers of British and American feminism. In her most famous work, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which was published in 1792 in the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft applies radical principles of liberty and equality to sexual politics. Rights of Woman is a devastating critique of the 'false system of education' which she argues forced the middle-class women of her time to live within a stifling ideal of femininity: 'Taught from infancy that beauty is women's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage seeks only to adore its prison'. Instead, Wollstonecraft dares to address women as 'rational creatures', and she urges them to aspire to a wider human ideal which combines feeling with reason and the right to independence. (Source: Penguin Web Site (http://www.futurenet.co.uk/Penguin/Academic/classics96/britclassicsauthor.html) Accessed 4 April 1997.) Click here to view a short biography on Mary Wollstonecraft, the mother of Mary Shelley (author of Frankenstein). Click here to read the first two paragraphs of Chapter II from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Question #15: In the first two paragraphs of Chapter II from Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman, what does she argue causes “the follies and caprices of our sex [women]…our headstrong passions and grovelling vices”? Enlightenment vs. Romanticism SOURCES OF INSPIRATION ATTITUDES AND INTERESTS SOCIAL CONCERNS CLASSICISM & RATIONALISM scientific observation of the outer world; logic clasical Greek and Roman literature ROMANTICISM examination of inner feelings, emotions; imagination literature of the Middle Ages pragmatic interested in science, technology concerned with general, universal experiences believed in following standards and traditions felt optimistic about the present emphasized moderation and selfrestraint appreciated elegance, refinement idealistic interested in the mysterious & supernatural concerned with the particular valued stability and harmony favored a social hierarchy interested in maintaining aristocracy concerned with society as a whole believed nature should be controlled by humans desired radical change favored democracy concerned with common people concerned with the individual felt that nature should be untamed sought to develop new forms of expressions romanticized the past tended towards excess and spontaneity appreciated folk traditions Adapted from chart in Prentice Hall Literature: The English Tradition (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1991): 631. The Enlightenment, while an era of great scientific and industrial progress, was unable to address the social, political, and emotional stressors seething under the surface. Revolution brewed and then finally exploded in France. New modes of expression blossomed. A new respect and love for the common man, for the individual, took root… The vanguard for this new era consisted of poets, each unique, all dedicated to the ideals of a new age… The Romantic Era William Blake (1757-1827) William Wordsworth (1770-1850) Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) Painter, Poet, Visionary “Father” of Romantic Poetry Poet of the Imagination “The Garden of Love” and “The Tyger” The Prelude and “Tintern Abbey” “Kubla Khan” and Rime of the Ancient Mariner “First Generation” “Second Generation” George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) John Keats (1795-1821) Scoundrel, Womanizer, Poet Romantic Revolutionary “Greatest” Romantic Poet? “She Walks in Beauty” and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage “Ode to the West Wind” and “Ozymandias” “La Belle Dame sans Merci” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn” End of Day 2 Instructions BEFORE you finish today: 1. Right click the mouse and choose Meeting Minder again. 2. Choose “Export.” 3. Choose “Export Now.” 4. The program will send your answers to Word. 5. In Word, choose print. 6. BEFORE exiting the program, get your paper and check it over. 7. When you are satisfied with your answers, turn them in and exit Word and Power Point.