chapter13 training energy systems

advertisement

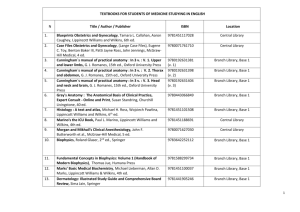

Section 5: Exercise Training and Adaptations Training the Anaerobic and Aerobic Energy Systems Chapter 13 Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Objectives • Define each of the following four principles of exercise training: (1) overload, (2) specificity, (3) individual differences, and (4) reversibility • Discuss the overload principle for training the (1) intramuscular high-energy phosphates, and (2) glycolytic systems; outline the specific adaptations in each system with exercise training Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Objectives (cont’d) • Describe how the following factors affect an aerobic training program: (1) initial fitness level, (2) genetics, (3) training frequency, (4) training duration, and (5) training intensity • List cardiovascular and pulmonary adaptations to aerobic training • Explain how exercise heart rate can establish the appropriate exercise intensity for aerobic training Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Objectives (cont’d) • Define the training-sensitive zone • Explain the need to adjust the training- sensitive zone for swimming and other forms of upper-body exercise • Explain the influence of age on (1) maximum heart rate, and (2) training-sensitive zone Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Objectives (cont’d) • Contrast continuous versus intermittent aerobic exercise training, including advantages and disadvantages of each • Outline potential benefits and risks of exercising during pregnancy Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Training Principles • Overload principle – Achieving the appropriate overload requires manipulating combinations of training frequency, intensity, and duration, with focus on exercise mode • Specificity principle – Refers to adaptations in metabolic and physiologic systems that depend on the type of overload imposed Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Training Principles (cont’d) • Individual differences principle – Variations in training responses among individuals • Reversibility principle – Detraining occurs relatively rapidly when a person quits their exercise training regimen Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Exercise Facts • Less than 13% of U.S. adults exercise regularly at sufficient intensity and duration to satisfy current guidelines to attain a minimum fitness level • More than 60% of those who initiate or renew a personal exercise program do not maintain it at the appropriate level Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Anaerobic System Changes • Adaptations with sprint–power training include: – Increased levels of anaerobic substrates – Increased quantity and activity of key enzymes that control the anaerobic phase of glucose catabolism – Increased capacity to generate high levels of blood lactate during all-out exercise Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic System Changes • Adaptations with aerobic training include: – Enhanced capacity to generate ATP aerobically – Increased mitochondria number and density – Improved ability to oxidize fatty acids, particularly triacylglycerols stored within active muscle, during steady-rate exercise Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic System Changes (cont’d) • Adaptations with aerobic training include: – An enhanced capacity to oxidize carbohydrate – Adaptations in both muscle fiber types, enhancing each fiber’s existing aerobic capacity and lactate threshold level without any great change in muscle fiber type Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Training and Carbohydrate Catabolism • Increased carbohydrate catabolism during intense aerobic exercise serves two important functions – Provides for a considerably faster aerobic energy transfer than from fat breakdown – Liberates about 6% more energy than fat per quantity of oxygen consumed Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Cardiovascular Adaptations • • • • • • Increased left ventricular cavity size Increased left plasma volume Increased stroke volume Reduction in submaximal heart rate Increased maximal cardiac output Increased maximal oxygen extraction Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Blood Lactate Metabolism • Aerobic exercise training extends the level of exercise intensity before the onset of blood lactate accumulation by: – Decreasing rate of lactate formation during exercise – Increasing rate of lactate clearance (removal) during exercise – Combining the effects of decreased lactate clearance and increased lactate removal Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic Training and Body Composition • Exercise only or exercise combined with calorie restriction reduces body fat more than fat lost with dieting only because exercise conserves the body’s lean tissue Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic Training and Body Heat Transfer • Well-hydrated, aerobically trained individuals exercise more comfortably in hot environments because of a larger plasma volume and more responsive thermoregulatory mechanisms Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Factors Affecting the Aerobic Training Response • • • • • • • Initial level of cardiorespiratory fitness Training frequency Training duration Training intensity Trainability and genes Maintenance of aerobic fitness gains Tapering for peak performance Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Formulating an Aerobic Training Program • General guidelines – Start slowly – Allow a warm-up period – Allow a cool-down period Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Guidelines for Children • • Children are not small adults Accumulate more than 60 minutes, and up to several hours per day, of age and developmentally appropriate activities for elementary school children Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Guidelines for Children (cont’d) • Some of the child’s physical activity each day should be in periods lasting 10 to 15 minutes or more and include moderate to vigorous activity; this activity will be intermittent in nature, involving alternating moderate to vigorous activity with brief rest and recovery periods Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Establishing Training Intensity • Train at – – – – O2max A percentage of V A percentage of maximum heart rate A perception of effort The lactate threshold Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Methods of Training • Anaerobic training • Aerobic training – Continuous – Intermittent Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Anaerobic Training • Intramuscular high-energy phosphates – Engaging specific muscles in repeated 5- to 10-second maximum bursts of effort overloads the phosphagen pool • Lactate-generating capacity – To improve energy transfer capacity by the short-term lactic acid energy system, training must overload this aspect of energy metabolism (10–60 sec) Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic Training: Continuous • Also known as long slow distance (LSD) • Requires sustained, steady-rate aerobic exercise • LSD training generally progresses at the relatively comfortable threshold intensity of 70% HRmax, although it can increase to the 85 or 90% level Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Aerobic Training: Intermittent • Also known as interval training • Provides periods of intense activity interspersed with moderate to low energy expenditure, which characterize many sport and life activities • Simulates this variation in energy transfer intensity through specific spacing of exercise and rest periods Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Interval Training • Four factors help to formulate the interval training prescription: – – – – Intensity of exercise interval Duration of exercise interval Duration of recovery interval Repetitions of exercise-recovery interval Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. The Overtraining Syndrome • 10% to 20% of athletes experience the syndrome of overtraining, or “staleness” • A result of complex interactions among biologic and psychologic influences Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Symptoms of Overtraining and Staleness • • • Unexplained and persistently poor performance and high fatigue ratings Prolonged recovery from typical training sessions or competitive events Disturbed mood states characterized by general fatigue, apathy, depression, irritability, and loss of competitive drive Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Symptoms of Overtraining and Staleness (cont’d) • • Persistent feelings of muscle soreness and stiffness in muscles and joints Elevated resting pulse and increased susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections (altered immune function) and gastrointestinal disturbances Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Symptoms of Overtraining and Staleness (cont’d) • • • Insomnia Loss of appetite, weight loss, and inability to maintain proper body weight for competition Overuse injuries Copyright © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.