Chapter 1 - Sacramento

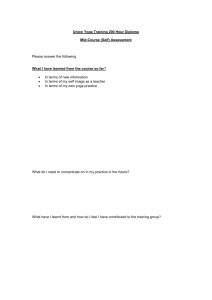

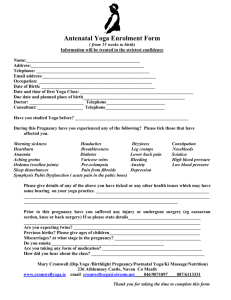

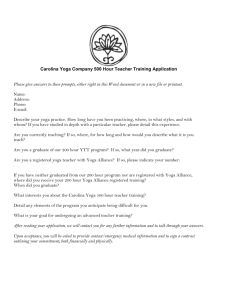

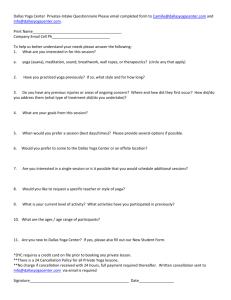

advertisement