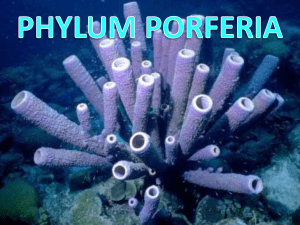

Porifera

Porifera

The phylum Porifera (the sponges) includes about 5000 species almost all of which are marine (there are about

150 freshwater species, members of the family

Spongillidae).

Sponges occur worldwide at all latitudes from the intertidal zone to the deep sea.

Range in size from a few millimeters to 2 meters across.

Porifera means “pore-bearing” and refers to the numerous pores and channels that permeate a sponge’s body.

Barrel sponge

Yellow tube sponge

Porifera

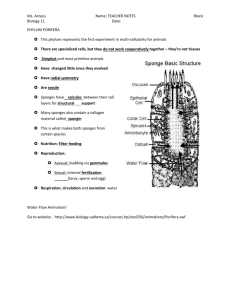

Sponges are the simplest multi-cellular organisms, but they lack the germ layers of more complex metazoans.

Have a cellular level of organization lacking true tissues and organs.

Body is a mass of cells imbedded in a gelatinous matrix (mesohyl) which is supported by a framework of spicules, as well as collagen and spongin fibers.

Glass sponge spicules

Figure 12.06

6.8

Spicules form the stiffening skeletal structure of the sponge and may be made of calcium carbonate, silica or spongin [collagen].

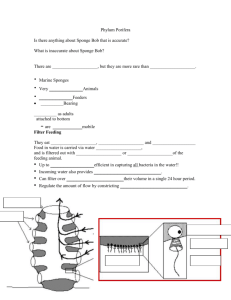

Porifera feeding

Sponges are sessile (they don’t move) and depend on water movement to bring in food and oxygen and remove wastes.

Sponges generate their own flow of water having a unique water current system.

Porifera feeding

Water enters through many small pores called ostia and exits through fewer, larger oscula .

Oscula

Porifera feeding

Openings are connected by a series of canals, which are lined by choanocytes

(the flagellated collar cells) that maintain the current and filter out food particles.

Choanocytes

Porifera feeding

The choanocyte’s collar consists of microvilli joined together by delicate microfibrils,which filter out tiny food particles.

The beating of the flagellum draws water through the collar and out the top.

Particles too big to pass through the collar get trapped in mucus and slide down the collar to the base where they are phagocytized.

Figure 12.12c

Porifera feeding

Sponges can filter enormous volumes of water as much as 20,000 times the volume of the sponge in 24 hours.

Sponges mostly consume bacteria and may filter as much as 90% of those passing through.

Carnivorous sponges

A few sponges, however, capture small prey, such as crustaceans.

Members of the family Cladorhizidae capture their prey using spicules that act like velcro to hold the prey. Cells then surround and digest the prey extracellularly.

Porifera feeding

Some sponges also supplement their filter feeding by hosting symbionts such as green algae, dinoflagellates or cyanobacteria that provide nutrients to the sponge.

Corals (which are Cnidarians not sponges) similarly have symbiotic algae that live with them.

Types of cells in Porifera

Sponge cells occur scattered through a gelatinous matrix called mesohyl.

Spicules are distributed through the mesohyl as are several different specialized cells types.

Sponge cell types

Archaeocytes : move around within the mesohyl. They are ameboid in appearance and carry out several tasks.

Phagocytize particles and receive particles for digestion from choanocytes.

Can differentiate into other specialized cell types.

Secrete structural components. Specialized archaeocytes called sclerocytes, spongocytes and collenocytes secrete respectively spicules, spongin and collagen.

Sponge cell types

Choanocytes : (collar cells) engage in filter feeding. One end is imbedded in mesohyl and the other end protrudes.

The protruding end of the choanocyte has a flagellum that moves water through a mesh-like collar where small particles are trapped.

Sponge cell types

Porocytes : These are tubular cells that in the simplest type of sponge (asconoid sponges) form tubes through the wall of the sponge and allow water to flow into the central chamber.

Sponge cell types

Pinacocytes: Layers of pinacocytes form a flat, thin epithelium-like layer (unlike true epithelium [a tissue] the individual cells are not joined by bands of extracellular proteins).

Pinacocytes cover exterior and some interior surfaces.

Pinacocytes have some ability to contract and some are arranged in bands around pores and use to regulate the flow of water in and out of the sponge.

Canal systems

Most sponges have one of three types of canal system:

Asconoid

Syconoid

Leuconoid

These systems differ from in each other in the increasing complexity.

Canal systems: asconoid

Asconoid is the simplest system. Water enters through pores into a single large central cavity (the spongocoel) which is lined with choanocytes.

There is a single large osculum.

Figure 12.07

Fig 6.3 a

Canal systems: syconoid

In syconoid canal systems there is still a single spongocoel and osculum, but the lining of the spongocoel is folded back to make radial canals lined with choanocytes.

Figure 12.09

6.3 b

6.5

Canal systems: leuconoid

Leuconoid organization is most complex and permits an increase in sponge size.

Most leuconoids form large masses with numerous oscula.

Clusters of choanocyte-lined chambers receive water from narrow incurrent canals and drive water into excurrent canals that eventually reach the osculum. There is no spongocoel.

Figure 12.07

6.3 c

Canal systems

The different grades of sponge canal complexity do not imply an evolutionary sequence as the leuconoid form has developed independently numerous times within different classes of sponges.

The leuconoid plan offers the significant advantage of increasing the proportion of flagellated cells relative to total sponge volume.

Sponge reproduction

Sponges reproduce both sexually and asexually.

Most sexually reproducing species are hermaphrodites (individuals produce both male and female gametes at different times).

Sperm are shed into the water and taken up by other sponges. Individuals with eggs use special cells called archaeocytes to transport sperm to the eggs.

Sponge reproduction

Zygotes develop into ciliated larvae that are released into the water and eventually settle and develop into a sponge.

Asexual reproduction is either by budding or more commonly the production of gemmules which are clusters of cells surrounded by a protective coat.

Figure 12.13

Gemmule

Totipotency

Sponge possess several different types of cells.

All sponge cells are totipotent and can give rise to any of the other types of cell.

A single cell can give rise to a new sponge or can self-assemble with other cells into a sponge.

(a sponge separated into its constituent cells will spontaneously reassemble).

Totipotency

Individual cells hook on to other cells almost as if as Dawkins suggests (p484)

“they were autonomous protozoa with sociable tendencies.”

Origins of multicellularity

Choanocytes the collar cells of sponges bear a striking resemblance to free-living unicellular choanoflagellates.

Choanoflagellate

Choanocytes

Choanoflagellates

Origins of multicellularity

There is general agreement that the origin of sponges and metazoans in general lies in a colony of flagellate protozoans.

In one type of colonial choanoflagellate (Proterospongia) the individual cells are embedded in a gel matrix and the cells are almost indistinguishable from choanocytes.

Molecular evidence also supports the close relationship between sponges and choanoflagellates.

Groups of sponges

There are three classes of sponges:

Class Calcarea

Class Hexactinellida

Class Demospongiae

Calcarea

Calcareous sponges whose spicules are made of calcium carbonate.

Tend to be small (<10cm) and tubular or vase shaped.

May be asconoid, syconoid or leuconoid in structure.

Figure 12.08

Clathrina canariensis (Calcarea)

Hexactinellida (glass sponges)

Skeleton is made of six-rayed siliceous spicules bound in a glasslike lattice. Nearly all are deep sea forms.

Body of hexactinellids consists of a single, syncytial tissue (mass of protoplasm containing many nuclei, but not divided into cells).

This bilayered syncytium encloses a collagenous mesohyl and various cells including choanoblasts which extend into the flagellated chamber through openings in the reticulum.

Figure 12.16

Figure 12.15

Calcarea

Hexactinellida

Demospongiae

The Demospongiae includes about 80% of all species and includes the freshwater

Spongillidae. Spicules siliceous, spongin or both.

All members are leuconoid and most of the large sponges are members of Demospongiae.

Loggerhead sponges may be a couple of meters in diameter.

Includes the bath sponges, which have only spongin skeletons.

Figure 12.17a

Figure 12.17c

Marine Demospongiae on a

Caribbean coral reef

Phylum Placozoa

Placozoans are tiny (<3mm), odd animals.

Consist of a few thousand cells that form a flat transparent layer, but with ventral and dorsal sides that differ in structure.

They feed by flowing over surfaces and digesting small items they encounter.

Only 4 cell types occur in Placozoans (cf.

16-20 in sponges and >200 in mammals).

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/phyla/placozoa/placozoa.html

Placozoans

Nothing is known about Placozoan behavior in the wild.

They were discovered first in a European aquarium in the 1880’s and have only been studied in the lab.

Placozoans

Because they are so simple, when these animals were first discovered it was thought they were the most primitive metazoans, even simpler than sponges.

However, the dorsal surface of Placozoans is a tissue layer of ciliated cylinder cells and non-ciliated gland cells which suggests they diverged after the sponges branched off from other animals.

There is some evidence that Placozoans may have diverged from other animals after the cnidarians

(jellyfish) split off and secondarily became simplified, but the phylogenetic picture is still unresolved.