Class 1 & 2 Powerpoint Presentation

advertisement

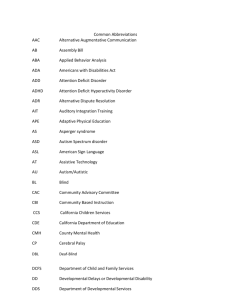

Definition of Developmental Disabilities by The Federal Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill or Rights Act of 2000 (Public Law 106-402) A Developmental Disability is a severe, chronic disability that: is attributable to a mental or physical impairment or combination of mental and physical impairments; is manifested before the person attains age 22; is likely to continue indefinitely; results in the substantial functional limitations in 3 or more of the following areas of major life activity: self-care receptive and expressive language learning mobility self-direction capacity for independent living economic self-sufficiency reflects the individual’s need for a combination and sequence of special interdisciplinary or generic services, individualized support, and other forms of assistance that are lifelong or of extended duration and are individually planned and coordinated. Definition of Developmental Disabilities by New York State Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities (1999) Developmental disabilities are a variety of conditions that become apparent during childhood and cause mental or physical limitation. These conditions include pervasive developmental disorders such as autism, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, mental retardation, and other neurological impairments” There are many causes of developmental disabilities that can occur before, during or after birth. Those occurring before birth include genetic problems, poor prenatal care, or exposure of the fetus to toxins including drugs and alcohol. Difficulties during birth, such as restricted oxygen supply to the infant, or accidents after birth can also cause traumatic brain injury resulting in developmental disabilities. Longer-term postnatal causes include malnutrition and social deprivation. DSM IV: Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood or Adolescence Mental Retardation (Coded on Axis II) Learning Disorders Motor Skills Disorder Communication Disorders Pervasive Developmental Disorders Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood Tic Disorders Elimination Disorders DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Mental Retardation (Coded on Axis II) A. Significantly subaverage intellectual functioning: an IQ of approximately 70 or below on an individually administered IQ test (for infants, a clinical judgment of significantly subaverage intellectual functioning). B. Concurrent deficits or impairments in present adaptive functioning (i.e., the person's effectiveness in meeting the standards expected for his or her age by his or her cultural group) in at least two of the following areas: communication, selfcare, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, selfdirection, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health, and safety. C. The onset is before age 18 years. Code based on degree of severity reflecting level of intellectual impairment: 317 Mild Mental Retardation: IQ level 50-55 to approximately 70 318.0 Moderate Mental Retardation: IQ level 35-40 to 50-55 318.1 Severe Mental Retardation: IQ level 20-25 to 35-40 318.2 Profound Mental Retardation: IQ level below 20 or 25 319 Mental Retardation, Severity Unspecified: when there is strong presumption of Mental Retardation but the person's intelligence is untestable by standard tests DSM IV Diagnostic criteria for Learning Disorder When individuals demonstrate abilities below the level that would be expected given their age and grade level in school based upon an arbitrary gap, they may be diagnosed with this mental disorder which should be further specified according to the particular academic function affected: Mathematics Disorder Reading Disorder Disorder of Written Expression Learning Disorder NOS DSM IV Diagnostic criteria for Learning Disorder Mathematics Disorder: A. Mathematical ability, as measured by individually administered standardized tests, is substantially below that expected given the person's chronological age, measured intelligence, and ageappropriate education. B. The disturbance in Criterion A significantly interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily living that require mathematical ability. C. If a sensory deficit is present, the difficulties in mathematical ability are in excess of those usually associated with it. Coding note: If a general medical (e.g., neurological) condition or sensory deficit is present, code the condition on Axis III. DSM IV: Motor Skills Disorder Developmental Coordination Disorder When a child's motor coordination falls substantially below that which would be expected, and this cannot be accounted for by a known physical illness or injury, this mental disorder may be diagnosed. A. Performance in daily activities that require motor coordination is substantially below that expected given the person's chronological age and measured intelligence. This may be manifested by marked delays in achieving motor milestones (e.g., walking, crawling, sitting), dropping things, "clumsiness," poor performance in sports, or poor handwriting. B. The disturbance in Criterion A significantly interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily living. C. The disturbance is not due to a general medical condition (e.g., cerebral palsy, hemiplegia, or muscular dystrophy) and does not meet criteria for a Pervasive Developmental Disorder. D. If Mental Retardation is present, the motor difficulties are in excess of those usually associated with it. Coding note: If a general medical (e.g., neurological) condition or sensory deficit is present, code the condition on Axis III. DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Communication Disorders These mental disorders of childhood affect listening, language and speech. These include the following specific disorders: Expressive Language Disorder Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language Disorder Phonological Disorder Stuttering Communication Disorder NOS DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Communication Disorders Expressive Language Disorder: A. The scores obtained from standardized individually administered measures of expressive language development are substantially below those obtained from standardized measures of both nonverbal intellectual capacity and receptive language development. The disturbance may be manifest clinically by symptoms that include having a markedly limited vocabulary, making errors in tense, or having difficulty recalling words or producing sentences with developmentally appropriate length or complexity. B. The difficulties with expressive language interfere with academic or occupational achievement or with social communication. C. Criteria are not met for Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language Disorder or a Pervasive Developmental Disorders. D. If Mental Retardation, a speech-motor or sensory deficit, or environmental deprivation is present, the language difficulties are in excess of those usually associated with these problems. Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurological condition is present, code the condition on Axis III. DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Severe impairment pervades broad areas of social and psychological development in children with these mental disorders . These include the following specific disorders: Autistic Disorder Asperger’s Disorder Childhood Disintegrative Disorder Rett’s Disorder Pervasive Developmental Disorder NOS DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Autistic Disorder : In children with this Pervasive Developmental Disorder there is substantial delay in communication and social interaction associated with development of "restricted, repetitive and stereotyped" behavior, interests, and activities. A. A total of six (or more) items from (1), (2), and (3), with at least two from (1), and one each from (2) and (3): (1) qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following: (a) marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction (b) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level (c) a lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest) (d) lack of social or emotional reciprocity DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Autistic Disorder : (2) qualitative impairments in communication as manifested by at least one of the following: (a) delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gesture or mime) (b) in individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others (c) stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language (d) lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Autistic Disorder : (3) restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following: (a) encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus (b) apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals (c) stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements) (d) persistent preoccupation with parts of objects B. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years: (1) social interaction, (2) language as used in social communication, or (3) symbolic or imaginative play. C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Rett's Disorder or Childhood Disintegrative Disorder. DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Asperger’s Disorder : In children with this pervasive developmental disorder language, curiosity, and cognitive development proceed normally while there is substantial delay in social interaction and "development of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities." A. Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following: (1) marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction (2) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level (3) a lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest to other people) (4) lack of social or emotional reciprocity DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Asperger’s Disorder : B. Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following: (1) encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus (2) apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals (3) stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements) (4) persistent preoccupation with parts of objects DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Pervasive Developmental Disorders Asperger’s Disorder : C. The disturbance causes clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. D. There is no clinically significant general delay in language (e.g., single words used by age 2 years, communicative phrases used by age 3 years). E. There is no clinically significant delay in cognitive development or in the development of age-appropriate self-help skills, adaptive behavior (other than in social interaction), and curiosity about the environment in childhood. F. Criteria are not met for another specific Pervasive Developmental Disorder or Schizophrenia DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Combined type Predominantly Inattentive Type Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder NOS Conduct Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Disruptive Behavior Disorder DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders A. Either (1) or (2): (1) inattention: six (or more) of the following symptoms of inattention have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level: (a) often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities (b) often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (c) often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (d) often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish school work, chores, or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand instructions) (e) often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (f) often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (such as schoolwork or homework) (g) often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., toys, school assignments, pencils, books, or tools) (h) is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (i) is often forgetful in daily activities DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders (2) hyperactivity-impulsivity: six (or more) of the following symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with developmental level: Hyperactivity (a) often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat (b) often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected (c) often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults, may be limited to subjective feelings of restlessness) (d) often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly (e) is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a motor" (f) often talks excessively DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Impulsivity (g) often blurts out answers before questions have been completed (h) often has difficulty awaiting turn (i) often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games) B. Some hyperactive-impulsive or inattentive symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 years. C. Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g., at school [or work] and at home). D. There must be clear evidence of clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning. E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic Disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative Disorders, or a Personality Disorder). DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood A. Feeding disturbance as manifested by persistent failure to eat adequately with significant failure to gain weight or significant loss of weight over at least 1 month. B. The disturbance is not due to an associated gastrointestinal or other general medical condition (e.g., esophageal reflux). C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., Rumination Disorder) or by lack of available food. D. The onset is before age 6 years. DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood Pica Rumination Disorder Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early childhood DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria Tic Disorders Tourette’s Disorder Chronic Motor or Vocal Tic Disorder Transient Tic Disorder Tic Disorder NOS DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Tic Disorders Tourette's Disorder A. Both multiple motor and one or more vocal tics have been present at some time during the illness, although not necessarily concurrently. (A tic is a sudden, rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic, stereotyped motor movement or vocalization.) B. The tics occur many times a day (usually in bouts) nearly every day or intermittently throughout a period of more than 1 year, and during this period there was never a tic-free period of more than 3 consecutive months. C. The onset is before age 18 years. D. The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., stimulants) or a general medical condition (e.g., Huntington's disease or postviral encephalitis). DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Elimination Disorders Encopresis With Constipation and Overflow Incontinence Without Constipation and Overflow Incontinence Enuresis DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria for Other Disorders of Infancy, Childhood or Adolescence •Other Disorders of Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence: •Selective Mutism • Separation Anxiety Disorder • Reactive Attachment Disorder of Infancy or Early Childhood • Stereotypic Movement Disorder • Disorder of Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence NOS Early Optimism and Over-promise (1836-1850) A report made by the British Government in 1858 concluded the following: 1. Guggenbuhl was guilty of deceiving people by calling his establishment KretinenHeilanstalt (treatment center for cretins), since at most one third of the inmates were cretins. The report went as far as to accuse Guggenbuhl of "smuggling in" normal children to present as cured. 2. Normal children were kept from attending the public schools by housing them at Abendberg. 3. Not a single cretin had ever been cured. 4. There was no medical supervision. The director was away from four to six months each year and made no provisions for a substitute. 5. While at first well-trained instructors had been employed, Abendberg had been without a teacher for several years. 6. Heating facilities, nutrition, water supply, ventilation in dormitories, and clothing were inadequate. 7. The director never kept records of the munificent donations received. 8. No records were kept about the patients' progress. Realistic Optimism of Dr. Samuel Howe (1850-1870) In 1846 Howe convinced the Massachusetts legislature to allocate $2500/year for the teaching and training of ten retarded children. After a successful experimental period, and institution was incorporated in 1848 under the name “Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth”. It is now known as the Walter E. Fernald State School. Howe can be considered the father of institutional care in the US and the one who advocated most explicitly that acting upon the problem of mental retardation was a public responsibility. Howe’s efforts were followed by the establishment of additional training schools throughout the US through the 1870s Difficulties in Coping with Urban Life and the Shift to Custodial Care (1870-1890) Quotes from documents Cited by Wolfensberger, W. (1969). The origin and nature of our institutional models. In Robert Kugel & Wolf Wolfensberer (Eds.) Changing patterns in residential services for the mentally retarded. Washington, D.C.: President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. “Give them an asylum with good and kind treatment; but not a school.” “A well-fed, well-cared-for idiot, is a happy creature. An idiot awakened to his condition is a miserab le one.” “They must be kept quietly, safely, away from the world; living like the angels in heaven, neither marrying nor given in marriage.” Difficulties in Coping with Urban Life and the Shift to Custodial Care (1870-1890) Dangerous Trends in Institutional Development Isolation: Protection of the deviant from the non-deviant Institutions were removed from population centers to pastoral surroundings described in idyllic terms, eg. “Garden of Eden”, “happy farm” Enlargement: Benefits the retardates by congregating large numbers so that the could “be among their own type.” Economization: Began with noble sentiment about the virtue of work for the retarded, but gave way to the view that they should be working to diminish the economic burden on the public. Social Darwinism and the eugenic alarm (1890-1914) H. H. Goddard's 1912 report of the Kallikak family Martin Kallikak, a soldier of the Revolution, produced an illegitimate son with a retarded tavern girl. This son turned out to be retarded, too, and went on to produce a line of prostitutes, alcoholics, epileptics, criminals, pimps, retardates, and infant casualties. Martin himself went on to marry a respectable woman of a good family and left progeny all of which were representative of the most respectable citizens Social Darwinism and the eugenic alarm (1840-1914) H. H. Goddard's 1912 report of the Edward’s family Jonathan Edward's family was contrasted to the Jukes and the Kallikaks, since he left 285 college graduates, of whom 65 became college professors, 13 college presidents, more than 100 lawyers, and 30 judges Social Darwinism and the eugenic alarm (1840-1914) Three main alternatives for “purging from the blood of the race innately defective strains: Marriage laws Sterilization Segregation Slow development of community alternatives: Post-World-War I to 1950 Specialized training through public schools Heavy emphasis on community integration and supervision Colony plan –prototypes of half-way houses and sheltered workshops Beginnings of government support for families Parole plan: retarded people were permitted to live in the community under the supervision of a social worker who took a personal interest in integrating them into the community Renewed Enthusiasm: 1950 – Present National Association for Retarded Children: Advocacy group wielded great influence at local and national levels Medical advances aiding survival of babies with biological defects Local groups of parents developed community-based alternative services 1961: President Kennedy appointed panel to review conditions for retarded and presented: “A Proposed Program for National Action to Combat Mental Retardation Landmark legislation: Maternal and Child Health and Mental Retardation Planning Ammendments Act (1963) Application of behavior analysis to overcome learning and behavior problems experienced by people with developmental disabilities Provisions of the Willowbrook Consent Decree Designating steps, standards and procedures to protect residents from abuses such a/J seclusion, corporal punishment, degradation, medical experimentation, and routine use of restraints. Six scheduled hours of program activity each weekday for all residents. Educational programs for residents including provision for the specialized needs of the blind, deaf and multi-handicapped. Well-balanced nutritionally adequate diets. Dental services for all. No more than eight residents living or sleeping in a unit. A minimum of two hours of daily recreational activities-indoors and out-and availability of toys, books, and other materials Provisions of the Willowbrook Consent Decree Eyeglasses, hearing aids, wheelchairs and other adaptive equipment where needed. ). Adequate and appropriate clothing. Physicians on duty 24 hours daily for emergency cases. A contract with one or more accredited hospitals for acute medical care. A full-scale immunization program for all residents within three months. Compensation for voluntary labor in accordance with applicable minimum wage laws. ;.. Correction of health and safety hazards, including covering radiators and team pipes to protect residents from injury, repairing broken windows, and removing cockroaches and other insects and vermin. Developmentally Disabled Assistance and Bill of Rights Act (1975) I. Persons with developmental disabilities have a right to appropriate treatment, services and habilitation for such disabilities. II. The Federal Government and the States both have an obligation to assure that public funds are not provided to any institutional or other residential programs for persons with developmental disabilities that— A. Does not provide treatment services, and habilitation which is appropriate to the needs to such persons or B. Does not meet the following minimum standards: 1. Provision of a nourishing, well-balanced daily diet to the persons with developmental disabilities served by the program 2. Provision to such persons of appropriate and sufficient medical and dental services 3. Prohibition of the use of physical restraint on such persons unless absolutely necessary and prohibition of the use of such restraint a punishment or a s a substitute for a habilitation program 4. Prohibition on the excessive use of chemical restraints on such persons and the use of such restraints as punishment or as a substitute for a habilitation program or in quantities that interfere with services, treatment, or habilitation for such persons. 5.Permission for close relatives of such persons to visit them at reasonable hours without prior notice 6. Compliance with adequate fire and safety standards as may be promulgated by the Secretary of Health, Education, & Welfare. Americans with Disabilities Act 1990 (Public Law 101-336) Purposes: I. to provide a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities; II to provide clear, strong, consistent enforceable standards addressing discrimination against individuals with disabilities; III. to ensure that the Federal Government plays a central role in enforcing the standards established in this Act on behalf of individuals with disabilities; IV. to invoke the sweep of congressional authority, including the power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment and to regulate commerce, in order to address the major areas of discrimination faced day to day by people with disabilities Reasons fro the ebb and flow of mental health ideology Caplan (1969) Acceptance of ideas has little to do with their intrinsic value. Community-oriented reforms did not succeed in the past for the following reasons: 1. A shortage of manpower to implement programs, which in part reflects inadequate training facilities. 2. A shortage of resources associated with the low priority accorded the mentally ill by the public and their legislators. 3. Theories concerning the etiology and treatment of mental disorder favored exciting new ideas and fads. At the turn of the century, the intellectual and scientific community was buzzing with new ideas in neuropathology and psychoanalysis. Optimistic treatment modalities linking patients back to their home communities were considered unrealistic and "old-fashioned.“ 4. The naivete and lack of understanding of psychiatrists about problems of community dynamics that complicated the implementation of their programs. Theories of psychic functioning cannot be formulated in a vacuum. Factors in the social, political, economic, and scientific milieu affect the manner in which theories are developed as well as the success of their implementation. Reasons fro the ebb and flow of mental health ideology Caplan (1969) Acceptance of ideas has little to do with their intrinsic value. Community-oriented reforms did not succeed in the past for the following reasons: 5. The tendency of psychiatrists to embrace panaceas and to hail each change as the solution to all difficulties. The system was oversold to the public and to fellow professionals. When shortcomings were revealed, there was a pendulum swing in the opposite direction with the entire system being jettisoned. 6. When public complaints about the failure of optimistic promises started to surface, psychiatrists tended to deal with such outside pressure by evasion rather than by direct confrontation. Psychiatrists retreated into their professional guild and lost touch with the realities of community life. 7. Faddish theories were entirely untested. By the time the shortcomings of expensive plans had been realized, so much propaganda and money had been spent that it was difficult to abandon or replace them.