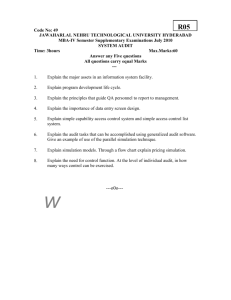

External Audit - Documents & Reports

advertisement