Space and Economics - Universidade de São Paulo

advertisement

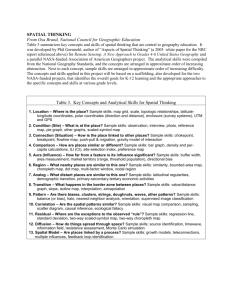

Space and Economics (or did Krugman deserve his Nobel Prize?) Danilo C Igliori 2015 Departamento de Economia Universidade de São Paulo Road map 1. Motivation 2. Facts 3. Questions 4. Concentration and Dispersion 5. Beyond my scope 6. Constant returns 7. Increasing returns 8. The Dixit-Stiglitz Approach 9. Krugman and the NEG 10. Growth and Agglomeration 11. Moving goods x moving ideas 12. Beyond geographical space Motivation: Understanding Economic Landscapes • Spatial analytical structures can help to shed light on a number of relevant economic issues; • The implications of the spatial configuration of economic activities are numerous, affecting, among other things: economic growth, industrial organisation, technological progress, welfare levels, inequality, and environmental problems; • Space has not to be necessarily geographical space. Facts: Agglomerations • The spatial distribution of population and economic activities is extremely unequal. • At any geographical scale it is the case that agglomerations are pervasive. • At a global scale it is easy to see that income and GDP are concentrated in a small number of countries. • However, the spatial concentration within countries is equally important, with economic landscapes reflecting the variety of cities and urban systems. Facts: Cities, Clusters and Industrial Districts • On the one hand we see large metropolises such as New York, London, Paris and Tokyo (or Sao Paulo, Mexico City and New Delhi). • On the other, there are specialised cities or regions forming industrial districts and economic clusters such as the Silicon Valley or the Third Italy. 2 Facts: Internal Structure of Cities • Agglomerations are also found at smaller scales, forming the internal structure of cities. • We see commercial districts where shops and restaurants cluster in neighbourhoods or even in a single street (one could also think of offices and job centres) • In the extreme case we can think of a shopping mall as a small agglomeration. Questions • What are the economics behind the tendency for people and firms to agglomerate in space? • What are the agglomeration advantages? Disadvantages? • What are the incentives for formation of urban systems (and rural areas)? • What are the implied dynamics generated by different spatial configurations? Concentration and Dispersion • In general, the spatial configuration of economic activity is the outcome of processes combining two groups of opposite forces: agglomeration forces and dispersion forces. • The recent literature of spatial economics emphasizes the fundamental link between these forces and the existence of transport costs, increasing returns to scale, externalities and imperfect market structures. Concentration and Dispersion Beyond my Scope • • • • • • German tradition (Christaller, Losch, Weber) Regional Science (Isard) Economic Geographers Kaldor Evolutionary economics Trade issues ...I have no ambitions to do justice to the field! Models with Constant Returns • Starret and the Spatial Impossiblity Theorem • Thunen’s monocentric cities • Hotelling and market areas The Role of Increasing Returns • Indivisibilities; • Adam Smith and market size; • Alfred Marshall and industrial districts; • Jane Jacobs and city life; • Limits to increasing returns (congestion effects). Innovation and Tacit Knowledge • Increasing returns to innovation is crucial for understanding the performance of urban areas; • Different places host different combinations of Marshall and Jacobs Externalities; • The concept of tacit knowledge is key in the theoretical literature. • Empirical testing is a major issue. Modern Modelling Approaches: The Increasing Returns Revolution • Dixit, Avinash K. and Stiglitz, Joseph E. "Monopolistic Competition and Optimal Product Diversity." American Economic Review, June 1977, 67(3), pp. 297-308 • Krugman, Paul R. (1979), "Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade", Journal of International Economics, 9(4) 469-479. • Romer, P. (1986). Increasing returns and long-term growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5): 1002-37. • Krugman, Paul, 1991. ‘Increasing Returns and Economic Geography’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 99(3), pages 483-99. The Dixit-Stiglitz Approach • Application: Industrial Organisation; • Structure: 2 sectors economy (one Walrasian; one facing monopolistic competition and subject to increasing returns); • Market size, love for variety and external economies. Utility Function 1 U M A Subutility Function 1 M m(i ) di 0 n 0 1 Love for Variety 1 1 (CES) • The parameter rho represents the intensity of the preference of variety. • When rho is close to 1 manufactured goods are nearly perfect substitutes. • As rho decreases toward zero, the desire to consume a greater variety of goods increases. Internal Increasing Returns l (i ) m (i ) Labour requirement in the manufacturing sector The Core-Periphery Model • The workhorse of the so-called New Economic Geography was first proposed by Krugman (1991) and has been labelled as the CorePeriphery Model. • Although recognising the value of the three sources of externalities originally proposed by Marshall, in the Core-Periphery Model Krugman adopts a highly parsimonious setup (DixitStiglitz) focused on increasing returns, pecuniary externalities and transport costs The C-P Model • The Core-periphery model has been celebrated for providing several insights about the geography of economic activities through behavioural and formalised models. • However, it has important limitations as well. Transport Costs (Samuelson’s Iceberg) 1 T rs Migration Equation r ( r ) r Source: Baldwin et al (2003) The 3 Effects • The mechanics of the model is driven by three effects: 1. market access, 2. cost of living, 3. market crowding. Tomahawk Diagram Source: Baldwin et al (2003) Policy Implications • threshold effects; • Discontinuities; • hysteresis. What’s New About NEG? ‘Since 1990 a new genre of research, often described as the ‘new economic geography’, has emerged. It differs from traditional work in economic geography mainly in adopting a modelling strategy that exploits the same technical tricks that have played such a large role in the ‘new trade’ and ‘new growth’ theories; these modelling tricks, while they preclude any claims of generality, do allow the construction of models that—unlike most traditional spatial analysis—are fully general-equilibrium and clearly derive aggregate behaviour from individual maximization. The new work is highly suggestive, particularly in indicating how historical accident can shape economic geography, and how gradual changes in underlying parameters can produce discontinuous change in spatial structure. It also serves the important purpose of placing geographical analysis squarely in the economic mainstream.’ Krugman (1998) Neary on NEG • The problem with this kind of model is that it is too simple. The focus is on monopolistic competition as the cause of agglomeration. • It is true there is some benefit to be derived from focussing on a single feature, this type of model is essential for understanding the world. • But no monocausal model can hope to capture the complexity of any applied problem, certainly not one where firms are all identical, infinitesimal in size, the CES function is so important to the outcome and externalities are dealt with in such a limited way. Glaeser on Krugman ‘Krugman (1991) shows that a brilliant theorist can explain cities without non-market interactions. But it is less obvious to me why one would want to do so. The flow of ideas and values that occurs through face-to-face interaction may be the most interesting feature of a city’ E. Glaeser (1999) Agglomeration and Growth • By introducing externalities associated with knowledge accumulation it is possible to merge spatial with growth models (see Baldwin et al 2003) • Key Issues: 1. The spatial equity-efficiency trade-off 2. Static losses x dynamic gains 3. Moving goods x moving ideas Global x Local Spillovers • Baldwin et al (2003) propose 2 different models: one with global spillovers and another with local spillovers. • They aim to capture the impact of knowledge transfers of different kinds. Local Spillovers - Forces • Endogenous growth and knowledge accumulation as agglomeration forces • Knowledge spillovers as a dispersion force Local Spillovers - Outcomes • Policies reducing transport costs for goods encourage agglomeration • Policies that lower the cost of transporting both goods and public knowledge may avoid extreme agglomeration. • Key: Congestion levels in central areas Glaeser and Kolhase • Transport costs are still important, but the relevant transport costs are likely to be for moving people, not goods. • The advantages from proximity to other people appear to come from saving the costs of providing and acquiring services and from improving the flow of knowledge. Transport Revenues Income x Density Business Services x Density FIRE – Finance, Insurance and Real Estate Manufacturing x Density Explaining the Past? • urban economics and the new economic geography need updating. • Both frameworks are analytically beautiful and remarkably apt characterisations of the city of the past. • But a new regional model, without centres and without transport costs for goods, will better capture the future of the city. Understanding the Future • Glaeser and Kohlhase view is that such a model would have the following basic elements: 1. Productivity would be a function of agglomeration because there are gains from people being able to interact. 2. The key transport mode – the automobile – travels much faster on highways than on city streets and is subject to congestion effects. Understanding the Future 3. Physical output is generally relatively costless to ship. 4. Even though output is almost costless to ship, most people produce services that require face–to–face interaction. Moving people is still expensive. 5. Land is heterogeneous and some places are nicer than others. Beyond Geographycal Space • Economic distances • Product characteristics • Political spectrum • Knowledge space Spatial Economic Analysis • http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/titles/17421772.asp