Chapter 22

Control:

The Management Control

Environment

McGraw-Hill

© 2004 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Management Control

This

chapter addresses the control

process and the use of accounting

information in that process.

The activity “strategy formulation”

develops strategies to attain an

organization’s goals.

Strategies change whenever a new

opportunity or a new threat is perceived.

22-2

Management Control Process

Process

by which managers influence

members of the organization to implement

the organization’s strategies efficiently and

effectively.

Takes goals and strategies as given.

Seeks to assure that the strategies are

implemented.

Includes planning.

22-3

Two Parts of Planning

A statement

Resources

of objectives.

required to achieve those

objectives.

22-4

Goals and Objectives

Terms

often used interchangeably.

Goals = broad, usually non-quantitative,

long run plans relating to the organization

as a whole.

Objectives = more specific, often

quantitative, shorter run plans for

individual responsibility centers.

22-5

The Environment

Four

facets of the management control

environment:

Nature of organizations.

Rules, guidelines and procedures that govern

the actions of the organization’s members.

The organization’s culture.

External environment.

22-6

The Nature of Organizations

Organization:

a group of human beings

who work together for one or more

purposes.

Managers

or the management: Leaders

who perform important tasks.

22-7

Tasks of Management

Determining goals.

Determining objectives to achieve the goals.

Communicating goals and objectives.

Determining tasks to be performed to achieve

objectives.

Coordination.

Matching individuals to tasks.

Motivating.

Observing/monitoring employee performance.

Taking corrective action as needed.

22-8

Organization Hierarchy.

= Layers of management with authority running from top

to bottom.

Optimal number of subordinates: (10?)

Organization chart.

Line units their activities are associated with achieving

the objectives of the organization. (They produce and

market goods or services.)

Staff units exist to provide support services to other

units and to the chief executive officer (CEO).

22-9

Rules, Guidelines, and

Procedures

Influence

Written,

the way members behave.

or verbal; formal, or informal.

22-10

Culture

Norms

of behavior determined by:

Tradition.

External influences.

Attitudes of senior management and the

board of directors (BOD).

22-11

External Environment

Everything

outside of the organization

itself.

E.g.,

customers, suppliers, competitors,

regulatory agencies.

22-12

Responsibility Accounting

Involves

a continuous flow of information

that corresponds to the continuous flow of

inputs into, and outputs from, an

organization’s responsibility centers.

Usage of various resources are measured

directly in or converted to a monetary

measure.

Focuses on responsibility centers.

22-13

Full Cost Accounting

Focuses

on goods and services.

Responsibility

accounting is a different

ways of slicing the same pie.

22-14

Responsibility Centers

Commonly

perform work related to several

products.

Inputs

to a responsibility center are called

cost elements or line items (on a

department cost report).

Costs

have three different dimensions:

22-15

Dimensions of Costs

Responsibility

center. Where was cost

incurred?

Product

dimension. For what output was

the cost incurred?

Cost

element dimension. What type of

resource was used?

22-16

Effectiveness and Efficiency

Effectiveness

= how well the responsibility

center does its job.

Efficiency

= the amount of output per unit

of input.

Lower

cost is more efficient.

22-17

Limitations of Actual Costs

Compared to Standard

Not

an accurate measure of efficiency for

at least 2 reasons:

Recorded costs are not precisely accurate

measures of resources consumed.

Standard are at best only approximate

measures of what resource consumption

ideally should have been in the circumstances

prevailing.

22-18

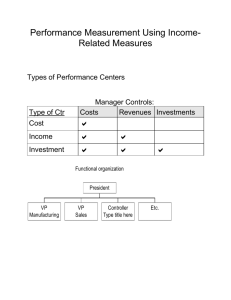

Types of Responsibility Centers

Important business goal: earn a satisfactory

return on investment:

ROI = (Revenues - Expenses) / Investment

Leads to 4 types of responsibility centers:

Revenue centers.

Expense centers.

Profit centers.

Investment centers.

22-19

Revenue Center

Responsible for outputs of center as measured

in monetary terms (revenues).

Not responsible for the costs of goods or

services that the center sells.

E.g., sales organization.

Also responsible for selling expenses (e.g.,

travel, advertising, point-of-purchase displays,

sales office salaries, rent).

22-20

Expense Centers

Responsible

for expenses (i.e., the costs)

incurred but does not measure its outputs

in terms of revenues.

E.g., production departments, staff units

such as accounting.

22-21

Standard or Engineered Cost

Center

Expense

center for which many of its cost

elements have standard costs established.

Differences

between standard costs and

actual costs are variances.

E.g.,

production cost centers, fast food

restaurants, and blood testing laboratories.

22-22

Discretionary Expense Center

Also

called managed cost center.

Difficult

to measure output in monetary

terms.

Production

E.g.,

support and corporate staff.

human resources, accounting, R&D.

22-23

Profit Centers

Performance

measured as difference

between revenues and expenses.

E.g.,

independent division of a company,

factory that sells its output to the

marketing division.

22-24

Advantage of Profit Center

Encourages

managers to act as if they are

running their own business.

22-25

Criteria for Profit Center

Involves extra record keeping.

Only useful if manager influences both revenues,

and costs.

If senior management requires service performed

by other responsibility center at no charge, then not

a profit center, e.g., internal audit.

If output is homogeneous (e.g., tons) no advantage

to monetary measure of revenue.

Multiple profit centers creates spirit of competition.

22-26

Transfer Prices

Price

at which goods or services are sold

between responsibility centers within a

company.

Revenue for selling center and cost for the

receiving center.

2 general types of transfer prices:

Market based price.

Cost based price.

22-27

Market-based Transfer Prices

Based

on price for same product between

independent parties, i.e., a market price or,

equivalently, an arm’s length price.

Adjusted for quantifiable differences such as

credit costs.

Where available is widely used.

Frequently not available.

22-28

Cost-Based Transfer Prices

When

Cost

no reliable market price is available.

plus a mark-up.

If

based on actual cost, little incentive to

reduce costs.

22-29

Transfer Pricing Issues

Negotiated

by responsibility centers or

set/arbitrated by top management.

Should

manager have freedom to use

alternative source?

Sub-optimization:

maximize profits for a

responsibility center may not maximize

profit for the consolidated company.

22-30

Investment Center

Responsible

for use of assets as well as

profits.

Expected

to earn a satisfactory return on

assets employed in the responsibility

center.

22-31

Measures of Performance

Return

on investment = Profit/Investment

Return

on assets = (net income) / (total

assets).

Split between ROS and Asset Turnover

income = Pre-interest profit –

(Capital charge * investment)

Residual

22-32

Residual Income

Residual

income = Income before taxes

less a capital charge.

Capital

charge is calculated by applying a

rate to the investment center’s assets or

net assets.

22-33

Advantage of Residual Income

over ROI

Encourages

managers to make all

investments whose return is greater than

the capital cost rate.

Example

22-34

Advantage of ROI Over

Residual Income:

ROI

measures are ratios that can be used

to compare investment centers of different

sizes.

Residual

income is an internal number that

is not reported to shareholders and other

outsiders.

22-35

EVA - overview

EVA is simply annual operating profit after-tax--minus a special charge for

the cost of capital. That charge corrects a glaring loophole in standard

accounting. In financial statements, companies pay nothing for equity

capital. It looks like free money. But equity is really very expensive. To raise

money from investors, companies must return at least as much as

shareholders could earn from a basket of stocks with the same risk--say,

12% a year. That's the cost of equity capital. If the company doesn't earn at

least its capital cost (blended to include the cost of debt), it can't keep

attracting new investment.

Far from being new, EVA, in effect, is one of the long- standing pillars of

finance theory: Until a company posts a profit greater than its cost of capital,

it's not making money for shareholders, no matter how good accounting

earnings look.

EVA is changing not only how managers run companies, but the way Wall

Street prices them. In the past three years, Credit Suisse First Boston and

Goldman Sachs have instructed their analysts to de-emphasize measures

like earnings per share and return on equity in favor of EVA

22-36

EVA Calculations - Part 1

To figure a company's or operation's economic value added, you must know two

things: the true cost of capital and how much capital is tied up. Here's a short guide to

get you on your way. Most companies pay for two kinds of capital, borrowed and

equity. It's easy to figure the cost of your borrowed capital--it's simply the interest rate

your banks and bondholders charge. But equity capital, the money stockholders

provide, is tricky. Although you don't have to write a check for it, don't think it's free.

The true cost is what your shareholders could be earning elsewhere.

To get that figure, you need to know that shareholders generally earn about six

percentage points more on stocks than on government bonds. With long-term

treasury rates around 7.5%, your cost of equity would be about 13.5%--more if you're

in a riskier than average industry. Assuming you use debt as well as equity capital,

the overall cost is the weighted average of the two.

22-37

EVA Calculations - Part 2

Now you need to figure out how much capital is tied up in your

business. That includes buildings, machines, and computers.

But there's more. What about investments in R&D or training?

Those are meant to pay off over the long haul, but accounting

rules say you have to write them off all at once. Forget the

accounting rules. Treat them as capital, and give them a useful

life. If, say, you're spending $20 million developing new products

this year, add that to your capital base, and add it back to

operating profits. If you expect the product to have a five-year

life cycle, deduct $4 million a year from capital--and operating

profits--in each of the next five years.

Now get out your calculator. Multiply your total capital by your

weighted average cost of capital. Compare that figure with your

after-tax operating earnings. If they are greater than your cost of

capital, have a cigar. You've got a positive EVA, which means

you're creating wealth for your shareholders.

22-38

EVA - Summary

EVA is powerful and widely applicable because in the end it doesn't

prescribe doing anything. If it tried, it would inevitably run aground in certain

unforeseen situations. Instead it is a method of seeing and understanding

what is really happening to the performance of a business. Using it, many

managers and investors see important facts for the first time. And in

general, they validate EVA's basic premise: If you understand what's really

happening, you'll know what to do.

22-39

Investment Center Issues

Asset allocation between centers.

How to value assets (e.g., historical cost or

replacement cost).

Most companies control investments in fixed

assets using capital investment (i.e., capital

budgeting) procedures addressed in Chapter 27.

Managers focus their day-to-day efforts on

managing current assets, particularly inventories

and receivables.

22-40

Non-monetary Measures

Non-monetary

as well as monetary

objectives.

E.g.,

Quality of goods or services,

customer satisfaction.

Management

by objectives (MBO) and

Balanced Scorecards in Chapter 24.

22-41