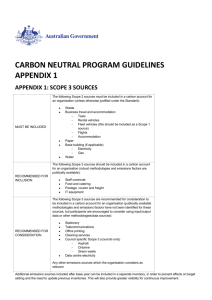

Key dates for the Special Review

advertisement