Lecture 15

advertisement

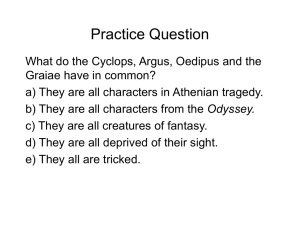

Ovid’s Metamorphoses An “Epic” of Desire and Transformation Metamorphoses = “Transformations” Latin poem, circa 8 C.E. Metamorphoses vs. Aeneid Aeneid: • a single, complex story • one heroic protagonist • subject: Roman mythic history and national identity Metamorphoses: • collection of (mostly mythological) tales • many characters (and many narrators) • subject: theme of transformation; human passions, especially desire Historical and Cultural Context 42 BCE 43 BCE 31 BCE 30 BCE 27 BCE 19 BCE ~19 BCE 18 BCE ~2 CE ~8 CE 8 CE 14 CE ~17 CE Julius Caesar assassinated Publius Ovidius Naso (“Ovid”) born Octavian Caesar (Augustus) defeats Marc Antony Ovid goes to Rome Octavian takes title “Augustus” Virgil’s Aeneid Ovid’s first poetry published; immediate success Julian Marriage Laws Ars Amatoria and Remedia Amoris published Metamorphoses finished Ovid exiled to Tomis for “a poem and a mistake” Augustus dies; succeeded by Tiberius Ovid dies in exile The Metamorphosis as “anti-epic” or “counter-epic” It looks like an epic: • epic meter (dactylic hexameter) • epic length (15 books) However, Ovid’s poem • lacks a unifying heroic narrative • deals with different themes (desire and love, rather than heroic virtues) • has a playful, witty tone • pokes fun at epic seriousness My mind now turns to stories of bodies changed Into new forms. O Gods, inspire my beginnings (for you changed them too) and spin a poem that extends From the world’s first origins down to my own time. - Book 1, lines 1-4 Some important themes in the Metamorphosis: • Transformation of bodies • • • • • Transformation of texts/stories/myths Desire: a destructive AND creative force Nature and Art Reality and Illusion Figure of the artist/poet/god In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty. - Genesis 1:1 Before there was land or sea or overarching sky, Nature’s face was one throughout the universe, Chaos as they call it: a crude, unsorted mass, Nothing but an inert lump, the concentrated, Discordant seeds of disconnected entities. … Yes, there was land around, and sea and air, But land impossible to walk, unnavigable water, Lightless air; nothing held its shape, And each thing crowded the other out. - Metamorphoses Book 1, lines 5-9, 15-20 Some god, or superior nature, settled this conflict, Splitting earth from heaven, sea from earth, And the pure sky from the dense atmosphere. … Then, the god who had sorted out this cosmic heap, Whoever it was, and divided it into parts, First rolled the earth, so it would not appear Asymmetrical, into the shape of a great sphere … - Metamorphoses Book 1, lines 21-23, 32-33 Man was born, whether fashioned from immortal seed By the Master Artisan who made this better world, Or whether Earth, newly parted from Aether above And still bearing some seeds of her cousin Sky, Was mixed with rainwater by Titan Prometheus And molded into the image of the omnipotent gods. … And so Earth, just now barren, A wilderness without form, was changed and made over, Dressing herself in the unfamiliar figures of men. - Metamorphoses Book 1, lines 79-89 My mind now turns to stories of bodies changed Into new forms. O Gods, inspire my beginnings (for you changed them too) and spin a poem that extends From the world’s first origins down to my own time. - Book 1, lines 1-4 Metamorphosis and Creation Metamorphosis as Creation • transformation is not just adaptation; it brings new forms into being • these new forms bear traces of their former selves Creation as Metamorphosis • Ovid’s gods do not create out of nothing; rather, they are agents of change and re-ordering • the world is constantly coming into being and being renewed, there is no single “moment of creation” Echo a nymph who could not stay quiet When another was speaking, or begin to speak Until someone else had – - Book 3, lines 388-390 He stands still, beguiled by the answering voice … beguiled: intensely attracted deceived, tricked And, seeking to quench his thirst, finds another thirst, For while he drinks he sees a beautiful face And falls in love with a bodiless fantasy And takes for a body what is no more than a shadow. Gaping at himself, suspended motionless In the same expression, he is like a statue Carved from Parian marble. - Book 3, lines 452-458 He desires himself without knowing it is himself, Praises himself, and is himself what is praised, Is sought while he seeks, kindles and burns with love. - Book 3, lines 464-466 Gullible boy, grasping at passing images! What you seek is nowhere. If you look away, You lose what you love. - Book 3, lines 473-475 Oh – that’s me! I just felt it, No longer fooled by my image. I’m burning with love For my very own self, burning with the fire I lit. What should I do? Beg or be begged? Why beg at all? What I desire I have. Abundance makes me a beggar. Oh, if only I could withdraw from my body and – Strange prayer for a lover – be apart from my beloved. - Book 3, lines 507-513 Meanwhile he sculpted With marvelous skill a figure in ivory, Giving it a beauty no woman could be born with, And he fell in love with what he had made. It had the face of a real girl, a girl you would think Who wanted to be aroused, if modesty permitted – To such a degree did his art conceal art. Pygmalion gazes in admiration, inhaling Passion for a facsimile body. … He kisses it and thinks His kisses are returned. - Book 10, lines 269-277, 280-281 Questions for Further Discussion: 1. The lecture observed a set of parallels between the creative/ordering/transformative acts of divine and human “artists.” How does the story of Daedalus and Icarus build on these parallels? Does the fate of Icarus develop or complicate our reading of poetic creation in the Metamorphoses? 2. It has been argued that the stories of Narcissus and Pygmalion are “mirror images” of one another: tragic and comic versions of a desire that creates its own object. Does reading these two parallel stories together suggest anything to you about the nature of desire as such? Are there important differences between the two stories that account for their disparate outcomes?