JOASwordsHennessyHeary2011

advertisement

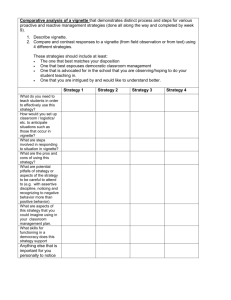

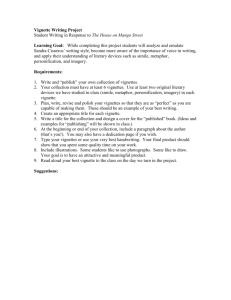

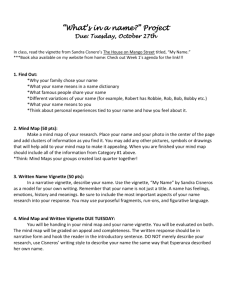

1 Adolescents' beliefs about sources of help for ADHD and depression Dr Lorraine Swordsa, Dr Eilis Hennessyb, Dr Caroline Hearyc a Trinity College Dublin, Children’s Research Centre, Dublin 2, Ireland (swordsl@tcd.ie) b University College Dublin, School of Psychology, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (eilis.hennessy@ucd.ie) c National University of Ireland Galway, School of Psychology, Galway, Ireland (caroline.heary@nuigalway.ie) 2 Adolescents' beliefs about sources of help for ADHD and depression The peer group begins to become a source of support during late childhood and adolescence making it important to understand what type of help young people might suggest to a friend with an emotional or behavioral problem. Three groups of young people participated in the study with average ages of 12 (N=107), 14 (N=153) and 16 years (N=133). All participants were presented with vignettes describing fictional peers, two of whom had symptoms of clinical problems (ADHD and depression) and a third comparison peer without symptoms. Results indicate that all participants distinguished between clinical and comparison vignette characters and they believed that the characters with clinical symptoms needed help. The 16-year-olds were more likely to differentiate between the two clinical vignettes in terms of the type of help suggested. The results are discussed in light of previous research on adolescents' understanding of sources of help for mental health problems. 3 Mental health and behavioural problems are relatively common during the teenage years (Ford, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2003; Lynch, Mills, Daly, & Fitzpatrick, 2006). Although most adolescents will not be diagnosed with a clinical condition, many will have contact with someone with a mental health problem over the course of their childhood and/or adolescent years. This might include having a sibling, classmate or friend with ADHD or depression. Understanding what young people know about such problems has, therefore, been of growing interest to researchers over the last decade. Indeed, the term ‘mental health literacy’ (Jorm, Korten, Jacomb, Christensen, Rodgers & Pollitt, 1997) has been used to refer to knowledge of mental health problems as well as the sources of help available and a number of studies on mental health literacy have been carried out with young people (e.g. Burns, & Rapee, 2006; Cotton, Wright, Harris, Jorm, & McGorry, 2006). What exactly do children and adolescents know about mental health and psychological problems? The picture that emerges from a review of studies published over the last twenty years is that children can identify peers who have behavioural problems from the pre-school years onwards but that the range of problems that children can identify increases as they get older (Hennessy, Swords & Heary, 2008). For example children who are different from their peers by virtue of higher levels of aggression are recognised before children who are different by virtue of being more withdrawn than their peers (Younger, Schwartzman, & Ledingham, 1985). The research also suggests that from middle childhood onwards, children can suggest a range of possible causes for mental health and behavioural problems (Chassin & Coughlin, 1983; Kalter & Marsden, 1977; Maas, Marecek, & Travers, 1978). These include explanations that are internal to the individual (such as being ‘born that way’) as well as external (such as inappropriate parenting) (Maas et al., 1978). Two studies 4 (Boxer & Tisak, 2003; Dollinger, Thelen & Walsh,1980) suggest that internal explanations for problems may become increasingly common in later adolescence, thus implying that understanding of mental health continues to change throughout the adolescent years. One aspect of adolescents’ understanding of mental health that has been of particular interest in recent years is the extent to which they are aware sources of help for mental health problems (Burns & Rapee, 2006; Hill, 1999). Adolescence has been the particular focus of this research for two reasons. The first is that adolescents are at greater risk of certain mental health problems (e.g. depressive disorders) than are younger children (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler & Angold, 2003; Ford et al., 2003). The second reason for the focus on adolescents is because of their increasing autonomy and greater emphasis on broadening social support to include extended family and peers (Levitt et al., 2005). For adolescents, therefore, the peer group may be an important source of information and support at a time when they are trying to cope with mental health problems. What these young people know about possible sources of help is thus extremely important as it may determine whether or not help is sought from qualified mental health professionals. Research from Australia and the United States of America highlights the fact that young people are likely to turn to their peer group for help if they experience a mental health problem. In their research with 15 to 17 year olds in Australia, Sheffield, Fiorenza and Sofronoff (2004) found that friends were the second largest source of help for participants who had experienced a mental illness or a personal emotional/behavioural problem. The results also demonstrated that the participants were significantly more willing to seek help for problems from informal sources (family and friends) than from formal sources (such as doctors, psychologists or 5 psychiatrists) and perceived fewer barriers to help seeking in the case of the informal support. Research by Wisdom and Agnor (2007) in the United States also found that adolescents who had a clinical diagnosis of depression reported that their peers had an important influence on how they coped with their illness. Their small qualitative study with 14 to 19 year olds emphasised that adolescents can have a beneficial role by becoming what they term ‘depression guides’ to depressed peers. A ‘depression guide’ was an adolescent who had experienced depression him/herself and who offered advice to others on such things as recognising the problem and seeking treatment. The authors also reported that peers could have an adverse influence through expressing negative attitudes about depression or its treatment. The importance of peers as a source of help is also emphasised by Offer, Howard, Schonert & Ostrov (1991) who reported that parents and friends were the most frequently used as sources of help across their sample of 17 year olds, however among those who were disturbed, friends were chosen as a source of help over parents. These findings emphasise the important role that peers play for teenagers who have a diagnosed mental health problem. The three studies just mentioned explored individuals’ personal experiences of help seeking for a range of personal and mental health problems. The literature also contains a number of studies that have focused on adolescents’ perceptions of appropriate sources of help for a peer who experiences a mental health problem. In a review of these studies Hill (1999) concluded that young people generally emphasise the central role of family and friends in providing help and support. This is confirmed by a number of more recent studies around the world. For example, Raviv, Sills, Raviv and Wilansky (2000) reported that adolescents in Israel would be more likely to recommend that a peer with depression seek help from a friend or parent than from a 6 formal source such as a psychologist or counsellor. Two studies in Australia also report high levels of belief in the value of informal sources of support that include family and friends (Cotton, et al., 2006; Wright et al., 2005). The study by Wright et al. (2005) had a very wide age range of participants (12 to 25 years) and found that the younger age group (12 to 17 years) were significantly more likely to believe that family and friends were the best form of help for peers with depression and psychosis than were the older group (18 to 25 years). The one exception to the finding that adolescents are more likely to refer peers to informal than to formal sources of help is reported in a study by Burns and Rapee (2006). Their study with adolescents in Australian schools found that young people placed school counsellors ahead of friends as the recommended source of support for a depressed peer. The authors note that schools in Australia typically have counsellors attached and that pupils are very familiar with their work. The findings of research so far indicate that from mid adolescence (about 14/15 years upwards) peers are an important source of help to young people who have themselves reported a mental health problem (Sheffield et al., 2004; Wisdom & Agnor, 2007). The research also suggests that young people are likely to recommend an informal source of help to a peer who is experiencing a problem (Hill, 1999; Raviv et al., 2000). The aim of the present study is to extend our understanding of the development of beliefs about appropriate sources of help for peers with mental health problems by including a wider age range of participants than has typically been included in such studies. There are several reasons for believing that this might prove useful. First, the peer group is believed to become increasingly important as a source of support for emotional and behaviour problems during late childhood and adolescence, however this age range has never been sampled in a single study to 7 determine age related differences in beliefs about sources of help. Second, little is known about the extent to which adolescents believe that different sources of help are appropriate for different types of mental health problem. ADHD and depression were chosen as the focus of the study because they are among the top three most commonly diagnosed clinical conditions during adolescence in Ireland (Lynch et al., 2006) and allow a comparison between an externalising and an internalising problem. Our specific questions were: i) Do adolescents distinguish between peers with ADHD and depression in judging their need for help? ii) Do adolescents differ in the total number of sources of help they suggest for peers with ADHD and depression? iii) Are there differences in the suggested sources of help for the peers with ADHD and depression? In answering each of these questions, the analysis also focused on differences across the three age groups of participants. Method Sampling Participants were recruited from randomly selected primary and second level schools from the Irish Department of Education and Science (DES) published lists of schools in the Leinster (Eastern) region of Ireland. In Ireland, children attend primary school for eight years, up to the age of 12/13 years and then transition to second level school. The sample was stratified using published data on receipt of additional assistance from the DES. Approximately 61.4% of primary schools and 31% of second level schools receive additional funds because the pupils are regarded as being at an economic disadvantage. Unfortunately the designation system has many flaws, not least the fact that many more primary schools are designated disadvantaged within 8 the system. In the final sample, 7 (63%) of the primary schools and 2 (22%) of the second level schools were designated disadvantaged. The proportions of sampled primary and second level schools were compared to the national proportions using goodness of fit tests. Neither the proportion of primary (2 (1, N=11) =0.024, p > .05) or second level schools (2 (1, N = 9) = 0.330, p > .05) that were designated as disadvantaged differed significantly from the proportions expected. The principals of 41 randomly selected schools were sent information packages, 20 (11 primary and 9 second level) agreed to participate (48.78%). Information sheets and forms requesting active consent were sent to the parents of 752 pupils. Student delivery of the consent forms was used as recommended by McMorris et al. (2004). In total 53% agreed to participate (n=398), 2.93% declined (n= 22), the remainder did not return the consent forms. Three pupils were absent on the day of data collection and two pupils in the oldest age group were excluded because they were so much older than the other participants in that group. The final participant count was 393. Participants were sampled from the final class of primary school (age 12/13) and from two second level school classes (age 14/15 and 16/17). All participants verbally assented to participation prior to data collection. The final study sample included 393 participants, 206 male and 187 female, aged from 12 years 5 months to 19 years. See Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of participants’ numbers, gender and ages by school year. Insert Table 1 about here Instruments 9 All instruments were presented to participants in a single booklet structured around three short descriptions (vignettes) of peers (see Appendix). Four forms of the booklet were produced in order to counter-balance the gender of the target peers described in the vignettes and to provide all participants with age appropriate information. Thus half of the booklets described a boy with ADHD and a girl with depression and half of the booklets described a girl with ADHD and a boy with depression. The order of presentation of vignettes was the same in all booklets: the character with ADHD appeared first, followed by a ‘comparison’ vignette depicting a character with good academic ability, the character with depression appeared in the final vignette. The age appropriate adjustments included, for example, information for younger participants that they would read about other ‘children’ of their age, for older participants this was adjusted to ‘young people’ or ‘teenagers’ of their age. The clinical vignettes used in the study were based on DSM criteria adapted from case studies presented in Carr (1999) and validated with 14 clinical psychologists practicing in Ireland. The clinical psychologists were sent six vignettes describing ADHD, conduct disorder, separation anxiety disorder, dog phobia, Asperger’s syndrome and depression. Clinicians were requested to rate each vignette on a 6-point scale for its accuracy as a description of the named disorder and its frequency as a problem presenting in their practice. ADHD, conduct disorder and depression were selected for inclusion in the study as they were given the highest accuracy ratings and were rated as common problems. The vignettes were used in a previous qualitative study by Hennessy and Heary (2009). Participants were asked two questions to ascertain their understanding of the vignette characters’ need for help and the possible sources of help available. The need for help was determined with a single item: ‘Do you think that X needs help?’ A 10 four point rating scale was used to capture their response: ‘Definitely Yes’; ‘Maybe yes’; ‘Maybe no’; ‘Definitely no’. This was followed by a single open-ended question: ‘If yes, who do you think could help X?’ Participants’ responses to these items are the primary focus of the present paper. Socio-demographic information on the participants’ families was gathered in a short questionnaire that was given to parents with the research information leaflet and consent form. The questionnaire asked parents to provide information on their age, employment status and highest level of education attained. For each of these questions a set of ‘tick box’ response categories was provided with, for example, age was grouped into ten year blocks and education grouped into six categories from ‘Intermediate/Group Certificate’ (the examination taken at the end of compulsory schooling in Ireland) to ‘Higher degree’. In addition there were two open-ended questions. One asked for the parent’s current job title (if they were employed) and a second asked for the number of children in the family. Procedure Participants filled in the questionnaires in their class group and completion took an average of 40 minutes. Ethics All parts of the research complied with the University College Dublin (UCD) Ethics Code of Good Practice and Research and the Code of Professional Ethics of the Psychological Society of Ireland. The research proposal was approved by the Human Research Ethics Sub-Committee of the UCD Ethics Committee. 11 Results Data analysis focused on three main questions: i) Do participants distinguish between peers with ADHD and depression in judging their need for help? ii) Do participants differ in the total number of sources of help they suggest for peers with ADHD and depression? iii) Are there differences in the suggested sources of help for the vignette characters with ADHD and depression? In all three questions there was also a focus on age related differences in participants’ responses. In the case of the first question, data was in the form of a four point rating scale for each character and was analysed using a two way (age X vignette) mixed measure ANOVA. Age was a between subjects variable and vignette was a repeated measure. In the case of the second question the data were the total number of different sources of help suggested by each participant and a two way mixed measure ANOVA was again used (age X vignette). In the case of the final question the data were categorical as they were derived from participant responses to an open-ended question on who could help the target characters. Therefore, these data were analysed using a series of chi-square statistics. Evaluation of the need for help Participants rated the target characters’ need for help on a 4-point rating scale with lower scores indicating a greater perceived need for help. Although the range of scores on this item was small this has been reported as having only minimal effects on level of significance when using analysis of variance (Glass, Peckham, & Sanders, 1972). Mean scores and standard deviations for each age group of participants are presented in Table 2. The figures show that in the case of the clinical vignettes all the means are ≤ 2.00 suggesting that participants of all ages generally believed that they were in need of help. The data presented in Table 2 also demonstrates that 12 participants generally did not believe that the character in the comparison vignette needed help. To examine age related differences in beliefs about the extent to which the vignette characters (ADHD, depression, comparison) needed help a two way mixed measure ANOVA was conducted. The ANOVA indicated a significant interaction between age and the vignette characters’ condition F (4, 774) = 3.09, p < .05, 2 = .016. Inspection of the graph of means indicated that the interaction was disordinal so tests for simple effects were conducted. The tests for simple effects indicated that there were no significant differences in the responses of the different age groups to the character with ADHD F (2, 774) = 0.26; p > 0.05 or the comparison character F (2, 774) = 0.06; p > 0.05. There were, however, significant differences in their responses to the character with depression F (2, 774) = 11.63; p < 0.05. Post hoc (Tukey/Kramer) analysis indicated that the 16year-olds were significantly different from both the 14-year-olds Q = 5.90, p < .01 and the 12 year olds Q = 6.06, p < .01. The 14-year-olds and the 12-year-olds did not differ significantly from one another Q = 0.16, p > .05. This indicates that the 16year-olds believed that the character with depression was significantly more in need of help than did the 14-year-olds or the 12-year olds. Tests for simple effects were also used to explore differences in responses to the three vignettes within each of the age groups of participants. In the sample of 12year-olds there were significant differences in responses to the vignette characters: F (2, 774) = 225.35, p < .05. Post hoc (Tukey/Kramer) analysis indicated that there were significant differences between responses to the comparison character and each of the clinical characters: ADHD: Q = 30.98, p < .01 and depression: Q = 26.88, p < .01. This indicates that the 12-year-olds believed that the characters with clinical problems were significantly more in need of help than the comparison character. The 13 two clinical vignettes were also significantly different from one another Q = 4.10, p < .01 such that the character with ADHD was judged as more in need of help than the character with depression. In the sample of 14-year olds there were significant differences in responses to the vignette characters F (2, 774) = 330.04. Post hoc (Tukey/Kramer) analysis indicated that there were significant differences between responses to the comparison character and each of the clinical characters: ADHD Q = 30.98, p < .01; depression Q = 27.54, p < .01. Again, the two clinical characters were judged as significantly more in need of help than the comparison character. The two clinical vignettes were also significantly different from one another Q = 3.44, p < .05 and again it was the character with ADHD who as judged as being more in need of help. In the sample of 16 year olds there were also significant differences in responses to the vignette characters F (2,774) = 351.55 p < 0.05. Post hoc (Tukey/Kramer) analysis indicated that there were significant differences between responses to the comparison character and each of the clinical characters: ADHD Q = 31.97, p < 0.01; depression Q = 33.28, p < .01. The two clinical characters were judged as significantly more in need of help than the comparison character. In this age group, however, estimates of the two clinical characters’ need for help were not significantly different from one another Q = 1.31 , p > .05. Table 2 about here Number of sources of help Participants who indicated that they believed the target character in each vignette needed help were asked an open-ended question about who could provide the help. They were free to make as many or as few suggestions as they wished. The initial analysis focused on the absolute number of different types of help made by the 14 participants. Participants suggested up to 5 sources of help and the means for each age group are presented in Table 3. Very few participants suggested help for the character in the comparison vignette and this is reflected in very small mean scores. Inspection of the means for the clinical vignettes indicates that older participants, in general, suggested more sources of help than younger participants and that all groups suggested more sources of help for ADHD than for depression. A two-way mixed measure ANOVA was conducted in order to explore age related differences. The ANOVA indicated that there was a significant interaction between vignette (ADHD, depression, comparison) and age (12, 14, 16 years) F (4, 780) = 4.43, p < .05, 2 = .02. Inspection of a graph of the means indicated that the interaction was ordinal so the main effects could be interpreted. There were significant main effects for vignette F (2, 780) = 347.78, p < .001, 2 = .47 and for age F (2, 390) = 5.81, p < .003, 2 = .03. Post hoc analyses (Dunnett C, equal variances not assumed) indicated that, regardless of vignette type, the oldest group (16-year-olds) gave significantly more help suggestions than the other groups (who were not significantly different from one another). Bonferroni pairwise comparison on the repeated measure (vignette) indicates significantly more sources of help were suggested for both clinical vignette characters than for the comparison character and that significantly more sources of help were suggested for the character with ADHD than the character with depression. Table 3 about here Sources of help suggested Participants’ responses to the open ended questions on who could help the vignette characters were coded by the second author into seven different categories. Definitions of each category with examples are presented in Table 4 (the 7th category ‘don’t know’ is omitted from the table). A second coder was then used to calculate 15 inter-rater reliability on 100% of the responses. This produced Cohen’s Kappa coefficients of .989 for ADHD and .984 for depression. In the very small number of cases where the first and second coder disagreed the initial code was used in the analysis. Only 30 (7.6%) participants mentioned any source of help for the character in the comparison vignette so this data has been omitted. Table 4 about here The frequency data for participants’ suggested sources of help for the vignette characters with ADHD and depression are presented in Table 5. As expected, in all three age groups family are perceived to be an important source of help for ADHD and depression, with teachers also being mentioned very regularly. Friends were not mentioned as frequently as had been expected, even in the group of 16-year-olds. Chi square analysis suggests that the 16-year-old participants made a greater distinction between the needs of the two vignette characters than either of the two younger age groups. Thus, there are no significant differences between sources of help suggested for ADHD and depression by the 12-year-old participants and just one difference for the 14-year-olds (who were more likely to recommend a mental health professional for ADHD than depression). In contrast, 16-year-olds distinguished between the vignette characters in their recommendations of friends, teachers and doctors. Table 5 about here Discussion The data analysis focused on three questions relating to participants’ beliefs about sources of help for fictional characters two of whom had clinical problems (ADHD and depression) and one who did not. Initial analysis of the responses 16 suggested that participants in all age groups believed that the characters in the clinical vignettes were in need of help. In contrast, their responses to the comparison vignette clearly showed that they did not believe that this character needed help. This finding is consistent with Peterson, Mullins and Ridley-Johnson (1985) who found that vignette characters who were portrayed as being depressed were given high ratings on a scale that measured their need for therapy. Similarly, Burns and Rapee (2006) found that teenagers distinguished between depressed and non-depressed vignette characters in terms of how much they would ‘worry’ about them. While the majority of participants in each age group rated the clinical vignette characters as needing help, there was also evidence of differences between younger and older participants. In particular, the findings suggest that the 12- and 14-yearolds were less convinced of the depressed character’s need for help than the 16-yearolds. Evidence for this comes from the fact that the 16-year-olds rated the depressed character as significantly more in need of help than either of the other two age groups and also that the 12- and 14-year-olds rated the character with ADHD as significantly more in need of help than the character with depression. The different responses of these age groups may be due to differences in their perceptions of when help is appropriate or in differing interpretations of the behaviour described. The findings are, however, consistent with the findings of a series of studies conducted by Younger in the 1980s. In these studies Younger demonstrated that children identified and distinguished aggressive behaviour at a younger age than withdrawn behaviour. For example, he found that there were developmental changes in children’s ability to recall withdrawn but not aggressive behaviour (Younger & Piccinin, 1989), that social withdrawal becomes increasingly important as a social schema as children got older (Younger & Boyko, 1987) and that aggressive behaviours formed a cohesive category 17 before withdrawn behaviours (Younger et al., 1985). While aggressive and withdrawn behaviours are clearly distinct from ADHD and depression, nonetheless they share certain similarities in that aggression and ADHD are both externalizing behaviours whereas depression and withdrawal are both internalising. The present study also found that there were age related differences in the participants’ ability to suggest sources of help for the two vignette characters with younger participants suggesting fewer sources of help for the character with depression. Looking at the absolute number of sources of help suggested by participants of different ages is a novel feature of this study. While other studies have asked participants open ended questions about sources of help (Burns & Rapee, 2006) they have typically focused only on the type of help suggested. In the case of Burns and Rapee, for example, they asked respondents to list sources of help and had 677 suggestions from 202 participants. It is not clear, however, whether these suggestions were evenly spread across all participants. The oldest participants in the present study are similar in age to the participants in Burns and Rapee’s (2006) study and like them were able to suggest multiple sources of help for the vignette characters. While Burns and Rapee (2006) focused on vignette characters with symptoms of depression, the present study also included a vignette describing symptoms of ADHD and found that significantly more sources of help were suggested for the latter than for the former. The findings of the present study support many previous studies that have found that children and adolescents believe that family members are important sources of help for mental health problems. Previous studies similarly reported that adolescents recommended family as a primary source of help for externalizing (Roberts, Johnson, & Beidleman, 1984), internalizing (Burns & Rapee, 2006) and ‘personal’ problems (Reetz & Shemberg, 1985). Similarly, parents were one of the 18 most commonly cited sources of help for affective problems in Raviv et al.’s (2000) research with adolescents in Israel. Finally, the combined group of ‘family and friends’ was the most commonly cited source of help for depression and psychosis by participants in the 12 - 17 year age group in research in Australia by Wright et al. (2005). In addition to family, participants in the present study believed that school teachers were an important sources of help for both clinical vignette characters. This stands in contrast to the findings of many other studies. Studies by Burns and Rappee (2006), Cotton et al., (2006) and Raviv et al. (2000) all found that a very low percentage of participants referred to teachers as a possible source of support for a peer with a mental health problem. Only one other study with young adolescents (Reetz & Shemberg, 1985) found that a substantial proportion of participants suggested teachers as a source of support. There are many possible reasons why participants in the present study should have been more likely to recommend teachers than in other studies, including the fact that all of the vignettes clearly placed the target characters in a school context as this was seen as one that would be familiar to all participants. While family and teachers represented important informal sources of support for young people in the present study, peers were typically seen as less important. Although this finding may seem surprising, in fact it is broadly consistent with the findings of Cotton et al. (2006) and Wright et al. (2005) because they combined family and friends into a single source of support. Raviv et al. (2004) looked separately at parents and friends as sources of support and found that friends came second to parents for a story depicting a young person with depression. It is important to note that the 16-year-olds in the present study were clearly distinguishing 19 between the value friends’ support for peers with ADHD and depression. They were more than twice as likely to suggest peer support for depression than for ADHD. Comparison of the sources of help suggested for the characters with ADHD and depression yielded some interesting differences between younger and older participants. In particular, the analysis demonstrated that the 16-year-olds were distinguishing between the help suggested for the two characters, whereas the younger participants were not. While the authors are not aware of other studies with adolescents that have compared suggested sources of help for different mental health problems, there is research evidence that young people distinguish between mental health problems in terms of likely causes (Maas et al., 1978, Roberts, et al., 1981). The fact that the present study included three age groups of adolescents suggests that understanding of mental health problems, and specifically how people with such problems can be helped, may continue to develop throughout adolescence. Some important limitations of the present study also need to be acknowledged. The first relates to the use of vignettes to elicit responses from participants. Vignettes are a very common way of presenting information on peers with mental health problems and have been widely used in other studies to avoid the use of labels (e.g. Francis, Boyd, Aisbett, Newnham, & Newnham, 2006, Raviv et al., 2000, Roberts et al., 1984, Wright et al, 2005). Nonetheless, questions remain about the extent to which children’s responses to characters described in vignettes are comparable to their responses to real peers. The only study to have done this comparison (Juvonen, 1991) looked at attitudes rather than knowledge about sources of help, however, the findings made it clear that there were significant differences in responses to hypothetical and real peers. Thus, any implication that young people might use their knowledge of sources of help, as demonstrated in the findings of this study, to advise 20 their friends or to seek advice themselves need to be treated with caution. It is also important to note that the order of the vignettes was not counter-balanced. The decision to present the vignettes in the same order to all participants was taken because the questionnaires already existed in multiple forms to allow for age differences in participants and to counter-balance the gender of the characters described in the vignettes. This is, however, a limitation of the study as the order of presentation may have influenced the participants’ responses. A further limitation is the low response rate from parents, only 55.93% of whom returned consent forms. In this our findings are not consistent with those of McMorris et al. (2004) who reported high response rates with student delivered forms. Our response rate is, however not too far below the consent rate reported in another large scale Irish study of adolescents (Lynch et al., 2006) who reported that 60% of forms were returned with a 2.8% refusal rate as compared with 2.93% in the present study. The findings of the present study indicate a growing awareness of professional sources of help for mental health problems with increasing age, but say nothing about the source of this knowledge. Hinshaw (2005) has pointed to the role that the media plays in conveying negative messages about mental health problems and these may serve as a primary source of information on this topic for young people. It is also the case that some schools are implementing short courses specifically designed to provide information on mental health and dealing with common problems and that exposure to these courses (in Ireland this is typically during the 12th year of school e.g Byrne, Barry & Sheridan, 2004) might increase awareness of sources of help. Understanding the sources of mental health knowledge is an important goal for future research on this topic given the fact that less than half of the oldest group of 21 participants suggested that either of the vignette characters could seek help from a mental health professional. 22 Acknowledgements This research was funded with a grant from the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences. The authors grateful acknowledge the assistance of all the school, parents and pupils who took part in the research. 23 References Boxer, P. & Tisak, M. S. (2003). Adolescents’ attributions about aggression: An initial investigation. Journal of adolescence, 26, 559-573. Burns, J. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2006). Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people's knowledge of depression and help seeking. Journal of Adolescence, 29(2), 225-239. Chassin, L., & Coughlin, P. (1983). Age differences in children's attributions for deviant behaviors. Psychiatry, 46, 181-185. Cotton, S. M., Wright, A., Harris, M. G., Jorm, A. F., & McGorry, P. D. (2006). Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(9), 790-796. Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G. & Anglold, A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 837-844. Dollinger, S. J., Thelen, M. H. & Walsh, M. L. (1980). Children’s conceptions of psychological problems. Journal of clinical child psychology, 9, 191-194. Ford, T., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2003). The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: The prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(10), 1203-1211. Glass, G. V., Peckham, P. D., & Sanders, J. R. (1972). Consequences of failure to meet assumptions underlying the fixed effects analyses of variance and covariance. Review of Educational Research, 42(3), 237-288. 24 Hennessy, E., & Heary, C. (2009). The development of children's understanding of common psychological problems. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 14(1), 42-47. Hennessy, E., Swords, L., & Heary, C. (2008). Children's understanding of psychological problems displayed by their peers: a review of the literature. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(1), 4-9. Hill, M. (1999). What's the problem? Who can help? The perspectives of children and young people on their well-being and on helping professionals. Journal of Social Work Practice, 13(2), 135. Hinshaw, S. P. (2005). The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(7), 714-734. Kalter, N., & Marsden, G. (1977). Children's understanding of their emotionally disturbed peers. II. Etiological factors. Psychiatry, 40, 48-54. Levitt, M. J., Levitt, J., Bustos, G. L., Crooks, N. A., Santos, J. D., Telan, P., et al. (2005). Patterns of Social Support in the Middle Childhood to Early Adolescent Transition: Implications for Adjustment Social Development, 14(3), 398-420. Lynch, F., Mills, C., Daly, I., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2006). Challenging times: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviours in Irish adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 555-573. Maas, E., Marecek, J., & Travers, J. R. (1978). Children's conceptions of disordered behavior. Child Development, 49(1), 146-154. McMorris, B. J., Clements, J., Evans-Whipp, T., Gangnes, D., Bond, L, Toumbourou, J. W. & Catalano, R. J. (2004). A comparison of methods to obtain active 25 parental consent for an international student survey. Evaluation Review, 28, 63-83. Morgan, S. B., Walker, M., Bieberich, A., & Bell, S. (1996). The Shared Activity Questionnaire. University of Memphis, Memphis, TN. Offer, D., Howard, K. I., Schoner, K. A. & Ostrov, E. (1991). To whom do adolescents turn for help? Differences between disturbed and nondisturbed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 623-630. Peterson, L., Mullins, L. L., & Ridley-Johnson, R. (1985). Childhood depression: Peer reactions to depression and life stress. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13(4), 597-609. Raviv, A., Sills, R., Raviv, A., & Wilansky, P. (2000). Adolescents' help-seeking behaviour: The difference between self- and other-referral. Journal of Adolescence, 23(6), 721-740. Reetz, M., & Shemberg, K. M. (1985). Fifth and sixth graders' attitudes toward mental health issues. Journal of Community Psychology, 13, 393. Roberts, M. C., Beidleman, W. B., & Wurtele, S. K. (1981). Children's perceptions of medical and psychological disorders in their peers. Journal of clinical child psychology, 10, 76-78. Roberts, M. C., Johnson, A. Q., & Beidleman, W. B. (1984). The role of socioeconomic status on children's percpetions of medical and psychological disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 13(3), 243-249. Sheffield, J. K., Fiorenza, E., & Sofronoff, K. (2004). Adolescents' Willingness to Seek Psychological Help: Promoting and Preventing Factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(6), 495-507. 26 Siperstein, G. N. (1980). Development of the Adjective Checklist: An instrument for measuring children’s attitudes towards the handicapped.Unpublished manuscript. Siperstein, G. N., & Bak, J. (1977). Instruments to measure children’s attitudes toward the handicapped: Adjective Checklist and Activity Preference List. .Unpublished manuscript. Wisdom, J. P., & Agnor, C. (2007). Family heritage and depression guides: Family and peer views influence adolescent attitudes about depression. Journal of Adolescence, 30(2), 333-346. Wright, A., Harris, M. G., Wiggers, J. H., Jorm, A. F., Cotton, S. M., Harrigan, S. M., et al. (2005). Recognition of depression and psychosis by young Australians and their beliefs about treatment. Medical Journal Australia, 183(1), 18-23. Younger, A. J., & Boyko, K. A. (1987). Aggression and withdrawal as social schemas underlying children's peer perceptions. Child Development, 58, 1094-1100. Younger, A. J., & Piccinin, A. M. (1989). Children's recall of aggressive and withdrawn behaviors: Recognition memory and likability judgments. Child Development, 60, 580-590. Younger, A. J., Schwartzman, A. E., & Ledingham, J. E. (1985). Age-related changes in children's perceptions of aggression and withdrawal in their peers. Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 70-75. 27 Table 1 Participant Numbers, Gender and Age by School Year Age Total Male Female Mean Age SD months 12 107 66 41 12yrs 5mths 5.52 14 153 73 80 14yrs 5mths 5.13 16 133 67 66 16yrs 8mths 7.96 28 Table 2 Participants’ mean ratings of the target characters’ need for help - lower scores indicate greater need for help Age Vignette character ADHD Mean Standard deviation Depression Mean Standard deviation Comparison Mean Standard deviation 12 14 16 Overall N = 107 N = 153 N =133 N=393 1.75 1.78 1.71 1.75 .78 .82 .74 .78 2.00 1.99 1.63 1.87 .87 .80 .69 .80 3.64 3.67 3.66 3.67 .72 .68 .74 .71 29 Table 3 Mean number of sources of help for vignette characters suggested by participants in each year group Age Vignette character ADHD Mean Standard deviation Depression Mean Standard deviation Comparison Mean Standard deviation 12 14 16 Overall N = 107 N = 153 N =133 N=393 1.19 1.35 1.47 1.34 .86 .95 1.02 .96 1.05 1.03 1.44 1.17 .90 .90 .96 .94 .08 .12 .09 .10 .37 .41 .38 .39 30 Table 4 Categories of sources of help suggested by participants Code Family Definition and examples All named relatives including extended family e.g. mother, father, sister, cousin, grandparent etc. Friend All references to a friend or peers Teacher All references to classroom teachers/teaching assistants of any type e.g. special teacher, special needs teacher. Doctor All general references to doctors that don’t included a named mental health specialization e.g. doctor, special doctor. Mental health All named mental health professionals and references to teachers with professional special training in counseling: psychiatrist, psychologist, shrink, therapist, counselor. Other Any individual that did not fall into one of the above categories e.g. social worker, nurse, God 31 Table 5 Types of help for vignette characters suggested by participants in each group1 Vignette type ADHD Age (N) Source of help Depression 12 year olds Family 43 (40.2%) 41 (38.3%) 0.06 (n= 107) Friend 10 (9.3%) 15 (14.0%) 1.14 Teacher 32 (30.0%) 25 (23.4%) 1.18 Doctor 7 (6.5%) 2 (1.9%) 2.90 professional 29 (27.2%) 19 (17.7%) 2.68 14 year olds Family 55 (35.9%) 41 (26.8%) 2.98 (n= 153) Friend 21 (13.7%) 24 (15.7%) 0.24 Teacher 41 (26.8%) 28 (18.3%) 3.16 Doctor 15 (9.8%) 11 (7.2%) 0.68 professional 60 (39.2%) 34 (22.2%) 10.36 ** 16-year-olds Family 34 (25.6%) 48 (36.1%) 3.13 (n= 133) Friend 19 (14.3%) 41 (30.8%) 9.07** Teacher 45 (33.8%) 27 (20.3%) 6.16** Doctor 26 (19.5%) 6 (4.5%) 14.20** 46 (34.6%) 57 (42.8%) 1.92 Mental health Mental health Mental health professional *p < .05 ** p < .01 32 1 Participants were free to suggest more than one source of help so cell totals do not correspond with numbers of participants 33 Appendix1 Vignettes ADHD Jake finds it very difficult to pay attention to what the teacher says and finds it difficult to concentrate on doing sums or reading or other work that the teacher gives him. Jake also finds it hard to stay sitting down when he is supposed to and often gets up or fidgets a lot. Often he has trouble waiting his turn in games and often interrupts when other people are doing things. Depression Lauren is an attractive girl who usually does okay in school. However, recently Lauren began to think that she is ugly, and not good at anything. She spends a lot of time thinking about all the things that she is not able to do and other sad thoughts. Sometimes she finds it hard to sleep at night so she is very often tired and upset during the day and cries a lot. 1 There were four versions of each vignette: male and female, younger and older. The younger version of the two vignettes are presented here.