Chapter No. 7

advertisement

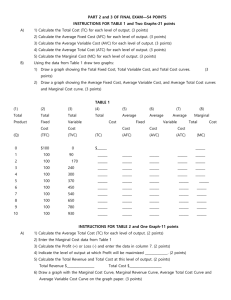

21 Pure Competition 21-1 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Learning objectives – In this chapter students will learn: A. The names and main characteristics of the four basic market models. B. The conditions required for purely competitive markets. C. How purely competitive firm maximize profits or minimize losses. D. Why the marginal cost curve and supply curve of competitive firms are identical. E. How industry entry and exit produce economic efficiency. 21-2 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Four market models A. Pure competition • entails a large number of firms, standardized product, and easy entry (or exit) by new (or existing) firms. B. Pure Monopoly • At the opposite extreme, pure monopoly has one firm that is the sole seller of a product or service with no close substitutes; entry is blocked for other firms. C. Monopolistic competition • is close to pure competition, except that the product is differentiated among sellers rather than standardized, and there are fewer firms. D. Oligopoly • is an industry in which only a few firms exist, so each is affected by the price-output decisions of its rivals. 21-3 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Pure Competition: Characteristics and Occurrence The characteristics of pure competition: 1. Pure competition is rare in the real world, but the model is important. Pure competition provides a norm or standard against which to compare and evaluate the efficiency of the real world. 2. There are many sellers means, that there are enough numbers so that a single seller has no impact on price by its decisions alone. 3. The products in a purely competitive market are homogeneous or standardized; each seller’s product is identical to its competitor’s (the market for the dollar). 4. Individual firms must accept the market price; they are price takers and can exert no influence on price. 5. Freedom of entry and exit means that there are no significant obstacles preventing firms from entering or leaving the industry. 21-4 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Demand from the Viewpoint of a Competitive Seller • The individual firm will view its demand as perfectly elastic. a perfectly elastic demand curve is a horizontal line at the price • The demand curve is not perfectly elastic for the industry: It only appears that way to the individual firm, since they must take the market price no matter what quantity they produce. P P Industry Firm S D=P=MR D Q 21-5 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Q Pure Competition $1179 P Firm’s Revenue Data 917 QD TR $131 0 131 1 131 2 131 3 131 4 131 5 131 6 131 7 131 8 131 9 131 10 TR 1048 $0 131 262 393 524 655 786 917 1048 1179 1310 MR ] $131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 ] 131 Price and Revenue Firm’s Demand Schedule (Average Revenue) 786 655 524 393 262 D = MR = AR 131 2 4 6 8 10 Quantity Demanded (Sold) 21-6 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 12 Definitions of average, total, and marginal revenue: Average revenue • is the price per unit for each firm in pure competition. Total revenue • is the price multiplied by the quantity sold. Marginal revenue • is the change in total revenue and will also equal the unit price in conditions of pure competition. 21-7 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Profit Maximization in the Short-Run: Two Approaches • In the short run the firm has a fixed plant and maximizes profits or minimizes losses by adjusting output; profits are defined as the difference between total costs and total revenue. • Three questions must be answered. 1. Should the firm produce? 2. If so, how much? 3. What will be the profit or loss? 21-8 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Profit Maximization in the Short Run Total Revenue-Total Cost Approach Price = $131 (1) Total Product (Output) (Q) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (2) Total Fixed Cost (TFC) (3) Total Variable Cost (TVC) $100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 $0 90 170 240 300 370 450 540 650 780 930 (4) (5) (6) Total Cost Total Revenue Profit (+) (TC) (TR) or Loss (-) $100 190 270 340 400 470 550 640 750 880 1030 $0 131 262 393 524 655 786 917 1048 1179 1310 $-100 -59 -8 +53 +124 +185 +236 +277 +298 +299 +280 Do You SeeGraph Profit The Maximization? Now Let’s Results… 21-9 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Profit Maximization in the Short Run Total Revenue-Total Cost Approach Total Economic Profit Total Revenue and Total Cost $1800 1700 1600 1500 1400 1300 1200 1100 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 21-10 Break-Even Point (Normal Profit) W 21.1 Total Revenue, (TR) Maximum Economic Profit $299 Total Cost, (TC) P=$131 Break-Even Point (Normal Profit) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Quantity Demanded (Sold) $500 400 300 200 100 Total Economic Profit $299 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Quantity Demanded (Sold) Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies G 21.1 1. Firm should produce if the difference between total revenue and total cost is profitable, or if the loss is less than the fixed cost. 2. In the short run, the firm should produce that output at which it maximizes its profit or minimizes its loss. 3. The profit or loss can be established by subtracting total cost from total revenue at each output level. 4. The firm should not produce, but should shut down in the short run if its loss exceeds its fixed costs. Then, by shutting down its loss will just equal those fixed costs. 21-11 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Marginal-revenue—marginal-cost approach • MR = MC rule states that the firm will maximize profits or minimize losses by producing at the point at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost in the short run. • Three features of this MR = MC rule are important. a. Rule assumes that marginal revenue must be equal to or exceed minimum-average-variable cost or firm will shut down. b. Rule works for firms in any type of industry, not just pure competition. c. In pure competition, price = marginal revenue, so in purely competitive industries the rule can be restated as the firm should produce that output where P = MC, because P = MR. 21-12 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Profit Maximization in the Short Run Marginal Revenue-Marginal Cost Approach MR = MC Rule (1) Total Product (Output) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (2) Average Fixed Cost (AFC) $100.00 50.00 33.33 25.00 20.00 16.67 14.29 12.50 11.11 10.00 (3) Average Variable Cost (AVC) (4) Average Total Cost (ATC) $90.00 $190.00 85.00 135.00 80.00 113.33 75.00 100.00 74.00 94.00 75.00 91.67 77.14 91.43 81.25 93.75 86.67 97.78 93.00 103.00 (5) Marginal Cost (MC) $90 80 70 60 70 80 90 110 130 150 (6) Marginal Revenue (MR) (7) Profit (+) or Loss (-) $131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 $-100 -59 -8 +53 +124 +185 +236 +277 +298 +299 +280 Surprise - Now Let’s GraphNow? It… DoNo You See Profit Maximization 21-13 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Using the rule, compare MC and MR at each level of output. At the tenth unit MC exceeds MR. Therefore, the firm should produce only nine (not the tenth) units to maximize profits. • Profit maximizing case: The level of profit can be found by multiplying ATC by the quantity, 9 to get $880 and subtracting that from total revenue which is $131 x 9 or $1179. Profit will be $299 when the price is $131. Profit per unit could also have been found by subtracting $97.78 from $131 and then multiplying by 9 to get $299. • Loss-minimizing case: The loss-minimizing case is illustrated when the price falls to $81. Table 21.4 is used to determine this. Marginal revenue does exceed average variable cost at some levels, so the firm should not shut down. Comparing P and MC, the rule tells us to select output level of 6. At this level the loss of $64 is the minimum loss this firm could realize, and the MR of $81 just covers the MC of $80, which does not happen at quantity level of 7. 21-14 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Marginal Cost and Short-Run Supply Continuing the Same Numeric Example… Supply Schedule of a Competitive Firm Quantity Maximum Profit (+) Price Supplied or Minimum Loss (-) $151 10 $+480 Profit max 131 9 +299 111 8 +138 91 7 -3 Loss min 81 6 -64 71 0 -100 Shut down 61 0 -100 The Schedule Shows the Quantity a Firm Will Produce at a Variety of Prices and Results 21-15 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Profit Maximization in the Short Run Marginal Revenue-Marginal Cost Approach MR = MC Rule W 21.2 Cost and Revenue $200 150 MR = MC P=$131 MC MR = P ATC Economic Profit 100 AVC A=$97.78 50 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Output 21-16 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 7 8 9 10 Profit Maximization in the Short Run Marginal Revenue-Marginal Cost Approach MR = MC Rule Loss Minimizing Case Cost and Revenue $200 Lower the Price to $81 and Observe the Results! 150 Loss A=$91.67 ATC AVC 100 MR = P P=$81 50 0 V = $75 1 2 3 4 5 6 Output 21-17 MC Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 7 8 9 10 • Shut-down case: If the price falls to $71, this firm should not produce. MR will not cover AVC at any output level. Therefore, the minimum loss is the fixed cost and production of zero. Table 21.4 and Figure 21.5 illustrate this situation, and it can be seen that the $100 fixed cost is the minimum possible loss. • Marginal cost and the short-run supply curve can be illustrated by hypothetical prices such as those in Table 236. At price of $151 profit will be $480; at $111 the profit will be $138 ($888-$750); at $91 the loss will be $3.01; at $61 the loss will be $100 because the latter represents the close-down case. • Note that Table 21.5 gives us the quantities that will be supplied at several different price levels in the short-run. • Since a short-run supply schedule tells how much quantity will be offered at various prices, this identity of marginal revenue with the marginal cost tells us that the marginal cost above AVC will be the short-run supply for this firm (see Figure 21.6). 21-18 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Profit Maximization in the Short Run Marginal Revenue-Marginal Cost Approach MR = MC Rule Short-Run Shut Down Case Cost and Revenue $200 Lower the Price Further to $71 and Observe the Results! MC 150 ATC V = $74 100 AVC MR = P 50 0 P=$71 1 Short-Run Shut Down Point P < Minimum AVC $71 < $74 2 3 4 5 6 Output 21-19 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 7 8 9 10 Marginal Cost and Short-Run Supply Cost and Revenues (Dollars) Generalizing the MR=MC Relationship and its Use e P5 MR5 d P4 ATC c P3 P2 P1 AVC b a This Price is Below AVC And Will Not Be Produced 0 Q2 Q3 Q4 Quantity Supplied 21-20 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies MC Q5 MR4 MR3 MR2 MR1 Marginal Cost and Short-Run Supply Generalizing the MR=MC Relationship and its Use Cost and Revenues (Dollars) Examine the MC for the Competitive Firm MC Above AVC Becomes the Short-Run Supply Curve Break-even (Normal Profit) Point e P5 AVC b a Shut-Down Point (If P is Below) This Price is Below AVC And Will Not Be Produced 0 Q2 Q3 Q4 Quantity Supplied 21-21 ATC c P3 P2 P1 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies MC MR5 d P4 S Q5 MR4 MR3 MR2 MR1 • Changes in supply • Changes in prices of variable inputs or in technology will shift the marginal cost or short-run supply curve. For example, a wage increase would shift the supply curve upward. • Technological progress would shift the marginal cost curve downward. • Using this logic, a specific tax would cause a decrease in the supply curve (upward shift in MC), and a unit subsidy would cause an increase in the supply curve (downward shift in MC). 21-22 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Cost and Revenue, (dollars) Marginal Cost & Short-Run Supply 21-23 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies MC2 S2 MC1 S1 AVC2 AVC1 Higher Costs Move the Supply Curve to the Left Quantity Supplied Cost and Revenue, (dollars) Marginal Cost & Short-Run Supply 21-24 Lower Costs Move the Supply Curve to the Right Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies MC1 S1 MC2 S2 AVC1 AVC2 Quantity Supplied Determining equilibrium price for a firm and an industry: • Total-supply and total-demand data must be compared to find most profitable price and output levels for the industry. Figure 21.7a and b shows this analysis graphically; individual firm supply curves are summed horizontally to get the total-supply curve S in Figure 21.7b. If product price is $111, industry supply will be 8000 units, since that is the quantity demanded and supplied at $111. This will result in economic profits. • Loss situation similar to Figure 21.4 could result from weaker demand (lower price and MR) or higher marginal costs. • Firm vs. industry: • Individual firms must take price as given, but the supply plans of all competitive producers as a group are a major determinant of product price. 21-25 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Changes in Supply (figure 27) b a Single Firm Industry p W 21.3 P S = ∑ MC’s s = MC Economic Profit ATC d $111 $111 AVC D 0 8 p 0 8000 Competitive Firm Must Take the Price that is Established By Industry Supply and Demand 21-26 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies P Profit Maximization in the long run • Several assumptions are made. 1. Entry and exit of firms are the only long-run adjustments. 2. Firms in the industry have identical cost curves. 3. The industry is a constant-cost industry, which means that the entry and exit of firms will not affect resource prices or location of unit-cost schedules for individual firms. • Basic conclusion to be explained is that after long-run equilibrium is achieved, the product price will be exactly equal to, and production will occur at, each firm’s point of minimum average total cost. Note 1. Firms seek profits and avoid losses. 2. Under competition, firms may enter and leave industries freely. 3. If short-run losses occur, firms will leave the industry; if economic profits occur, firms will enter the industry. 21-27 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • The model is one of zero economic profits, but note that this allows for a normal profit to be made by each firm in the long run. 1. If economic profits are being earned, firms enter the industry, which increases the market supply, causing the product price to gravitate downward to the equilibrium price where zero economic profits are earned (Figure 21.8). 2. If losses are incurred in the short run, firms will leave the industry; this decreases the market supply, causing the product price to rise until losses disappear and normal profits are earned (Figure 21.9). • Long-run supply will be perfectly elastic; the curve will be horizontal. In other words, the level of output will not affect the price in the long run. 21-28 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Supply Readjustment Single Firm Industry p P S1 MC ATC $60 $60 50 50 S2 MR D2 40 40 D1 0 100 p 0 80,000 90,000 100,000 An Increase in Demand Temporarily Raises Price Higher Prices Draw in New Competitors Increased Supply Returns Price to Equilibrium 21-29 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies P Supply Readjustment Single Firm Industry p P S3 MC ATC $60 $60 50 50 S1 MR D1 40 40 D3 0 100 p 0 80,000 90,000 100,000 P A Decrease in Demand Temporarily Lowers Price Lower Prices Drive Away Some Competitors Decreased Supply Returns Price to Equilibrium 21-30 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Pure Competition and Efficiency 1. Productive efficiency occurs where P = minimum AC; at this point firms must use the least-cost technology or they won’t survive. 2. Allocative efficiency occurs where P = MC, because price is society’s measure of relative worth of a product at the margin or its marginal benefit. And the marginal cost of producing product X measures the relative worth of the other goods that the resources used in producing an extra unit of X could otherwise have produced. In short, price measures the benefit that society gets from additional units of good X, and the marginal cost of this unit of X measures the sacrifice or cost to society of other goods given up to produce more of X. a. If price > marginal cost, then society values more units of good X more highly than alternative products the appropriate resources can otherwise produce. Resources are underallocated to the production of good X. 21-31 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies b. If price < marginal cost, then society values the other goods more highly than good X, and resources are overallocated to the production of good X. • • • • Allocative efficiency implies maximum consumer and producer surplus. Combined consumer and producer surplus is maximized at equilibrium. Any quantity less than equilibrium would reduce both consumer and producer surplus. Any quantity greater than equilibrium would occur with an efficiency loss that would subtract from combined consumer and producer surplus. 21-32 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Long-Run Equilibrium Competitive Firm and Market Single Firm P=MC=Minimum ATC (Normal Profit) Market MC S Price Price ATC MR P P D 0 Qf Quantity 0 Qe Quantity Productive Efficiency: Price = Minimum ATC Allocative Efficiency: Price = MC Pure Competition Has Both in Its Long-Run Equilibrium 21-33 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Efficiency Gains From Entry: The Case of Generic Drugs • Competitive Model Predicts Lower Price and Greater Output With Increased Efficiency When New Producers Enter Market • Example is Patented Drugs • Patents Enable Greater Profits in Support of R&D and Accelerated Cost Recovery • After Patent Period Generics Enter Market • Profits Decrease and Quantities Increase • Combined Consumer and Producer Surpluses Increase 21-34 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Efficiency Gains From Entry: The Case of Generic Drugs New Producers Enter Market a Price S • As Price Initial Patent Price Decreases to f, b c P 1 • Consumer Surplus abc d f P 2 Increases to adf • Producer and Consumer Surplus is D Maximized Q1 Q2 Together as Quantity Shown by the Gray Results: Greater Quantity at Lower Prices Triangle as Predicted by the Competitive Model 21-35 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Key Terms • pure competition • pure monopoly • monopolistic competition • oligopoly • imperfect competition • price taker • average revenue • total revenue • marginal revenue • break-even point • MR=MC • short-run supply curve 21-36 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • long-run supply curve • constant-cost industry • increasing-cost industry • decreasing-cost industry • productive efficiency • allocative efficiency • consumer surplus • producer surplus Next Chapter Preview… Pure Monopoly 21-37 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • B. There are four major objectives to analyzing pure competition. • 1. To examine demand from the seller’s viewpoint, • 2. To see how a competitive producer responds to market price in the short run, • 3. To explore the nature of long-run adjustments in a competitive industry, and • 4. To evaluate the efficiency of competitive industries. 21-38 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 21-39 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies