Paper_NewTestamentII_PaulandBaptism_firstrevision

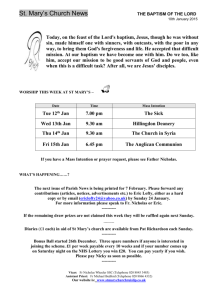

advertisement

Metaphors Come From Somewhere: The Liturgical Background of Colossians 2:11-15 Richard M. Wright Introduction to the New Testament II Dr. Sandra Hack Polaski Exegetical Paper June 10, 1997 Abstract Colossians 2:11-15 is a passage that has generated considerable controversy among scholars. It appears to be a reference to or discussion of baptism within an epistle that is intended to refute those that would impose human made philosophies and regulations upon the Colossian church. The passage is difficult in its grammar, its vocabulary, and its frame of reference. One way to approach the passage is to focus on the metaphor of putting off (clothes?) inherent in the terms απεκδυω and απεκδυσις. This metaphor may reflect the early Christian practice of baptism in which those being baptized disrobed for baptism and then were reclothed after the ritual. The passage is interpreted primarily as an exposition on the theological significance of baptism: baptism is being buried and raised with Christ, and is a saving event in the life of the Christian. Such an interpretation challenges the typical Baptist understanding of baptism, which sees the ritual as purely or primarily symbolic. One of the more difficult passages in the epistle to the church at Colossae is Col 2:11-15. With its ambiguous syntax, unusual vocabulary, and dense use of metaphor, it has defied the best efforts of scholars to achieve a consensus concerning some of the most basic questions regarding these verses. One of the things I find striking about the passage is the reference to baptism in Col 2:12, one of many allusions to baptism that can be detected throughout the epistle. What understanding of baptism does Col 2:12 appear to reflect? How does that understanding match what we know about the theology and practice of baptism in the early church? If we consider the theological and liturgical background of the reference to baptism in Col 2:12, how does that inform our reading of this verse, of this passage, and of this epistle? Such an exegesis may in turn challenge our understanding and appreciation of the ritual of baptism, particularly within the Baptist Christian community. Before proceeding further, it is necessary to establish the text of the passage, as well as to offer a working translation. The text of Col 2:11-15 is relatively free from major text critical problems, although there are a few which merit discussion. The addition of τωv αμαρτιωv after τoυ σωματoς in 2:11 is an awkward insertion that is attested no earlier than the 6th-7th centuries; it should be rejected primarily on grammatical grounds.1 Although the textual evidence for βαπτισματι in 2:12 is as good as for βαπτισμω,2 the latter is to be preferred on the grounds that βαπτισμoς is the It appears in 2 D1 Ψ 075 and a few others, and is absent in P46 * A B C D* F G P and others; see Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Kurt Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th ed., Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1993, 526, critical apparatus. The phrase τoυ σωματoς της σαρκoς "the body of the flesh" is far more plausible than τoυ σωματoς τωv αμαρτιωv της σαρκoς "the body of the sins of the flesh"; see Eduard Lohse, Colossians and Philemon, trans. William Poehlmann and Robert Karris, Hermeneia (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1971), 103n62. 1 2 For βαπτισματι, * C D2 Ψ 33 and others; for βαπτισμω, P46 2 B D* F G and others. less common term for baptism in the NT, and thus less likely to have served as a correction for βαπτισμα.3 Whether to read υμας or ημας in 2:13 is more difficult.4 If 2:13c-15 is indeed a hymnic or confessional fragment, then ημας is clearly preferable;5 although υμας is still quite possible if it resumes υμας in 2:13a. The juxtaposition of υμας in 2:13c with ημιv in 2:13d is still awkward but not impossible;6 the author has chosen to include himself with his audience, either to make a theological point,7 or because he is so moved by the thought being expressed.8 As even a small sampling of commentaries will reveal, the grammar and vocabulary of Col 2:11-15 are difficult, and ambiguities abound.9 Part of my approach to the text is to respect as much as possible these inherent ambiguities; we should resist the tendency to pick one interpretation-translation to the exclusion of other possibilities. Therefore the translation offered here is based partly on my desire to retain as much as possible the inherent difficulties of the text,10 and partly on particular interpretations that will be explained later in this study. 3 See M. Harris, Colossians and Philemon, Exegetical Guide to the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991), 103-104. Both readings are well documented: υμας in 2 D F G Ψ and others; ημας in P46 B 33 323 and a few others. 4 5 If ημας is original, then the shift from "you" in 2:9-13b to "us" in 2:13c and following requires explanation. Lohse commented: "In v 13c the confessing community speaks using the first person plural....A high degree of probability exists for the assumption that a fragment of a confession formulated in hymnic phrases underlies vss 14-15"; Colossians and Philemon, 106. 6 See Harris, Colossians and Philemon, 106-107. See especially Peter O'Brien, Colossians, Philemon, Word Biblical Commentary (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1982), 123: "_μ_ς is repeated for the sake of emphasis; its omission from some manuscripts was probably due to its being thought by scribes to be superfluous while its replacement with _μ_ς in P46 B 33 etc. was probably to bring it into line with the following _μ_v. In other words, it is the reading which explains the others." 7 So Markus Barth and Helmut Blanke, Colossians, trans. Astrid Beck, Anchor Bible Commentary, vol 34B (New York: Doubleday, 1994), 32:" Paul the Jew seems to include himself expressly in the proclamation concerning the forgiveness of sins. He thus says expressly that there is no forgiveness of sins for gentiles without forgiveness for Jews. The former is a shareholder with the latter." 8 So R. E. O. White, "Colossians," Broadman Bible Commentary, vol. 11 (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1971), 238: "Paul was ever deeply moved by the thought of being granted access into the favor of the Most High. As so often, he breaks the thread of the passage to include himself; and he remembers how complete God's pardon is." 9 Harris' commentary is particularly useful for its systematic listing of the various interpretations-translations possible for each phrase or verse. 10 Compare the highly interpretive translation of this passage in the NIV: "In his you were also circumcised, in the putting off of the sinful nature, not with a circumcision done by the hands of men but with the circumcision done by Christ, having been buried with him in baptism and raised with him 2 Colossians 2:11-15 In him you also were circumcised with a circumcision not of human hands, in the complete removal of the body of flesh, in the circumcision of Christ; (12)having been buried with him in baptism,11 wherein you were also raised with (him) through faith in the active power of God who raised him from (the) dead. (13)And while you were dead in trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, he made you alive with him, forgiving you (of) all trespasses, (14)having erased our certificate of debt with its decrees which stood against us; and he took it away, nailing it to the cross. (15)Having stripped the powers and authorities, he displayed (them) publicly, leading them in a victory celebration therein.12 (11) The preliminary working translation above attempts to take into account the structure of the passage, which is based on parallel dependent clauses, the use of finite verbs versus participles, and on the repetitive use of (εv) αυτω/_, a recurring pattern which can even be seen in the verses immediately preceding our passage for exegesis. (6) ... εv αυτω περιπατειτε... (7) ... εv αυτω... (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) ... oτι και εστε εv αυτω κατoικει... εv αυτω πεπληρωμεvoι... εv _ και περιετμηθητε πετιτoμη αχειρoπoιητω εv τη απεκδυσει τoυ σωματoς της σαρκoς εv τη περιτoμη τoυ Χριστoυ συvταφεvτες αυτω εv τω βαπτισμω εv _ και <---?---> εv _ και συvηγερθητε δια τησ πιστεως της εvεργειας τoυ [θεoυ τoυ εγειραvτoς αυτov εκ vεκρωv through your faith in the power of God, who raised him from the dead. When you were dead in your sins and in the uncircumcision of your sinful nature, God made you alive with Christ. He forgave us all our sins, having canceled the written code, with its regulations, that was against us and that stood opposed to us; he took it away, nailing it to the cross. And having disarmed the powers and authorities, he made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross" (emphasis added). 11 On the subtle distinction between βαπτισμoς "baptizing, immersion, ritual washing" and βαπτισμα "baptism (of John), (Christian) baptism," see A. Oepke, s.v. βαπτω, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, ed. Gerhard Kittel, 11 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964-), 1:529-546. 12 With some hesitation I reject the translation of 2:15 which Roy Yates bases on his thorough analysis of this verse: "Having stripped himself in death, He boldly made an open display of the angelic powers, leading them in triumphal (festal) procession on the cross"; "Colossians 2.15: Christ Triumphant," New Testament Studies 37 (1991): 591. Some of the reasons for which I dispute his well argued interpretation will be presented below. 3 (13) συv αυτω (14) και υμας vεκρoυς ovτας τoις παραπτωμασιv και τη [ακρoβυστια της σαρκoς υμωv συvεζωπoιησεv υμας χαρισαμεvoς ημιv παvτα τα παραπτωματα εξαλειψας τo καθ' ημωv χειρoγραφov τoις δoγμασιv o υπεvαvτιov ημιv ηρκεv εκ τoυ μεσoυ πρoσηλωσας αυτo τω σταυρω απεκδυσαμεvoς τας αρχας και τας εξoυσιας εδειγματισεv εv παρρησια θριαμβευσας αυτoυς και αυτo (15) εv αυτω. Notice the repetition of (εv) αυτω/_ which occurs throughout the passage. The fourfold repetition of εv αυτω in Col 2:6-10 clearly refers to Christ; therefore we should be inclined to interpret αυτω throughout 2:11-15 as referring back to Christ in 2:6. The final εv αυτω therefore also refers to Christ, and forms a kind of inclusio with εv αυτω in 2:6. Hence Harris' argument that εv αυτω in 2:15 refers primarily to τω σταυρω is unlikely. But how do we deal with εv _ in 2:11, 12? Since it follows the fourfold repetition of εv αυτω in 2:6-10, we presume that the shift from αυτω to _ is unimportant, and the antecedent is still Christ. But εv _ in 2:12 follows immediately after the phrase εv τω βαπτισμω and may be parallel with it, and so this second occurrence of εv _ may refer to τω βαπτισμω. But why should the writer shift from εv αυτω to εv _ and then use εv _ for two different referents? I submit that the text deliberately is ambiguous. It invites us first to interpret the first εv _ in conjunction with the previous four instances of εv αυτω which refer to Christ, and then to read the second εv _ in 2:12 as parallel with εv _ in 2:11.13 But the possibility of a secondary reading should be considered. The second εv _ parallels εv τω βαπτισμω, and the first εv _ in 2:11 anticipates this reading.14 Verses 11 and 12 can be read both ways, as a discussion of what has happened to the addressees in Christ, and as what happened to the addressees in baptism. We can also note the grammatical parallel between εv _ περιετμηθητε...εv τη απεκδυσει...εv τη περιτoμη in 2:11 and εv τω βαπτισμo εv _ συvηγερθητε in 2:12. Both the finite verbs and the dependent εv clauses are parallel, suggesting that the writer is indeed making a formal comparison between circumcision and baptism, a point which some commentators deny.15 This 13 "In him you also were circumcised... in him you also were raised." See Rudolf Schnackenburg, Baptism in the Thought of St. Paul, trans. G. R. Beasley-Murray (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1964), 67-68. 14 "In which (baptism) you also were circumcised... having been buried with him in baptism, in which you were raised." See, however, G. R. Beasley-Murray, who argues against this interpretation on the grounds that εv _ (Christ) και συvηγερθητε causes the awkward expression, "In him you also were raised with him"; Baptism in the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962), 154. 15 In favor of seeing the comparison, see Schnackenburg, Baptism, 67-68; White, "Colossians," 236-237; Ralph Martin, Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon, Interpretation (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1991), 115. For those who see no attempt to equate or compare circumcision and baptism in these verses, see O'Brien, Colossians, Philemon, 115; Harris, Colossians and Philemon, 103. 4 grammatical link between circumcision and baptism in 2:11-12 must be kept in mind as we consider the understanding of baptism which Col 2:11-15 conveys. Our passage Col 2:11-15 also bears strong resemblance to another passage that refers to baptism, Rom 6:3-8. This resemblance has not gone unnoticed, some commentators having gone so far to suggest that Col 2:11-15 is a commentary on Rom 6:3-8, expositing and clarifying the theology underlying Romans 6.16 This apparent literary dependence alone raises certain questions about the date and authorship of Colossians. Paul's letter to the Romans, after all, was certainly the last letter to be written by him before being arrested in Jerusalem (see Rom 15:22-31; Acts 22:22 and following), around 55-56 C.E. Those who regard Colossians as written by Paul himself suggest,17 in conjunction with the reference to captivity in Philemon, that it was written while Paul was in captivity, either in Ephesus, Caesarea, or Rome. An Ephesian setting is least likely, given the apparent dependence of Col 2:11-15 on Romans 6.18 And yet the apparent link between Colossians and Philemon (compare Col 4:7-10 and Philemon 9-23) is undeniable. An Ephesian captivity is the most likely setting for Philemon,19 Colossians appears to have been written from the same location as Philemon, and yet an Ephesian captivity is highly improbable for Colossians! This problem with the relationship of Colossians to Philemon, plus the literary dependence of Col 2:11-15 on Romans 6, plus the other reasons that some scholars have presented,20 lead me to conclude, with some hesitation, that 16 Beasley-Murray, Baptism in the NT, 139, 152, 155; Schnackenburg, Baptism, 70. 17 Remarkably enough, none of the commentators I consulted for this exegesis argued against Pauline authorship. If the Pauline authorship of Colossians is so disputed, why is it difficult to find commentators who interpret the epistle from the perspective that it is pseudonymous, perhaps having been composed by students or coworkers of Paul, a Pauline school of Christianity? See Luke T. Johnson, The Writings of the New Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), 357-359; Lohse, Colossians and Philemon, 2-3; O'Brien, Colossians, Philemon, xlii-l; Barth and Banke, Colossians, 23-26; Frank Stagg, "Colossians," in Mercer Commentary on the Bible, eds. Watson Mills and Richard Wilson (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1995), 1235-1237. 18 Contra Martin, Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon, 96-97. Romans 15 reads as if Paul is on his way to Jerusalem, not as if he expects to be in prison for a long enough period to hear about and respond to a crisis at the church in Colossae. 19 Martin, Ephesians, Colossians, Philemon, 96-97; Charles H. Cosgrove, "Philemon," in Mercer Dictionary of the Bible, 1263. 20 See Johnson, Writings of the NT, 355-359. These reasons include: (a) εκκλησια as the church universal rather than the church local; (b) Christ referred to as κεφαλη rather than God; (c) a "higher" Christology than is found in the undisputed Pauline epistles; (d) the distinctive vocabulary and style of Colossians; (e) the Haustafeln in Col 3:18-4:1, which are more easily explained as reflecting a period after the dead of Paul. Some have argued against (d) by pointing out that most of the unique vocabulary in Colossians may be due to Paul appropriating the distinctive language of his opponents; Barth and Banke, Colossians, 23-25. But Colossians and Ephesians share 10 words that occur nowhere else in the NT, 15 that occur elsewhere in the NT but not in the undisputed Pauline writings; O'Brien, Colossians, Philemon, xlii-xliii. This suggests that the distinctive vocabulary of Colossians is due to more than the particular situation which it addresses. 5 Colossians was probably written not by Paul himself but by some of his followers-students-coworkers who were already making use of the Paul's literary legacy. But Colossians cannot be dated overly late, since it is already cited by a one of the church fathers around 140 C.E.. And Ephesians, which is dependent upon Colossians, might have been quoted by Ignatius of Antioch as early as 115 C.E.21 Colossians may have been composed during the first years after the death of Paul, probably in Asia Minor near Colossae, given the letter's close relationship to Philemon.22 If Col 2:11-15 is indeed a kind of commentary on Romans 6, then we should consider how and why Col 2:11-15 is distinctive. First, Romans 6 lacks the repetition of (εv) αυτω/_ which structure Col 2:11-14. Second, the Colossians passage employs metaphors lacking in Romans 6. In Romans 6:3-8 there are no references to circumcision, or certificates of debt which are nailed to the cross,23 or stripping of powers and authorities.24 Third, the Colossians passage uses expressions which do not appear in Rom 6:3-8, terms such as απεκδυω and χαριζω. I submit that Col 2:11-15 should be read in light of what we know about the practice of baptism in the early church. One of our earliest witnesses to how the early church understood and practiced baptism is the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, a bishop of Rome writing around 200 C.E.25 Hippolytus describes a lengthy process of preparation for baptism, a period of catechism that 21 On the relationship between Ephesians and Colossians, see Johnson, Writings of the NT, 367-370. On the early citation of Colossians and Ephesians, see Johnson, ibid., 532. 22 Robert A. Wild, "Colossians, The Letter of Paul to the," in Harper's Bible Dictionary, ed. Paul Achtemeier, 176. 23 The term χειρoγραφov, which occurs only here in the NT, means simply a certificate of debt, an IOU; Walter Bauer, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 2nd ed., revised and augmented (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979), 880b; Eduard Lohse, s.v. χειρoγραφov, TDNT, 4:435-436; and Roy Yates, "Col 2,14: Metaphor of Forgiveness," Biblica 71 (1990): 248-259. 24 The translation and interpretation of Col 2:15 is particularly difficult, partly because of the individual words involved (απεκδυσαμεvoς...εδειγματισεv...θριαμβευσας), partly because of the grammar of the verse (who is the subject of απεκδυσαμεvoς? the referent of εv αυτω?), partly because of the overall picture being presented. For example, what are τας αρχας και τας εξoυσιας? Angels? Evil spirits? The elemental principals of the cosmos? Most commentators see the verse as describing some sort of defeat of and triumph over the spiritual forces of evil to which the opponents want the Colossian believers to devote themselves; Martin, Ephesians, Colossians, Philemon, 115-116; Lohse, Colossians and Philemon, 111-112. Others see the metaphor as more neutral: God (the subject of απεκδυσαμεvoς) is simply exposing της αρχας και της εξoυσιας for what they are; Barth and Banke, Colossians, 332-336. One scholar argues that the metaphor is chiefly positive: Christ is the victor, and της αρχας και της εξoυσιας participate with him in a festal procession which celebrates what he accomplished through his work on the cross; Roy Yates, "Colossians 2.15: Christ Triumphant," New Testament Studies 37 (1991): 573-591. 25 Burton Scott Easton, trans., The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1934). All references to Hippolytus' Apostolic Tradition will be to this work. One of 6 lasted three years on average.26 The catechumenal process included periodic exorcisms; during the final days leading up to the baptismal rite, candidates were exorcised daily by the bishop. What is noteworthy is how the ritual of baptism itself was performed: They [those who are to be baptized] shall remove their clothing....Then, after [renouncing Satan and his servants and his works, and after being exorcised one last time], let him give him over to the presbyter who baptizes, and let the candidates stand in the water, naked....And he who is being baptized goes down into the water.27 Baptism involved going down into the water, the complete immersion of the person being baptized. Afterwards those who have been baptized are anointed, they dry themselves, are clothed, and brought into the church.28 Perhaps we should relate the unusual use of απεκδυσις in 2:11 (and απεκδυω in 2:15) to the early practice of removing clothes for baptism, and then dressing again immediately afterwards. Although the exact form απεκδυω (and απεκδυσις) appears to be an intensive form--"fully put or take off"--invented by the writer of Colossians,29 the verb εκδυω is attested elsewhere with the meaning "strip; divest oneself; take off, undress." It is sometimes employed with the ordinary sense of removing clothes in classical literature (such as by Herodotus and Aristophanes), and it appears in the LXX in Isa 32:11 with the clear sense of bare oneself (as a gesture of repentance and mourning). Granted, Paul does use εκδυω in a figurative sense in 2 Cor 5:4, referring to the shedding of the body in death. But we should consider the possibility that the related expressions απεκδυω and απεκδυσις are used not only in a figurative but also in a literal sense in Col 2:11, 2:15 (and 3:9), particularly in light of the frequent use of εvδυω--which means to put on (clothes), sometimes in a figurative sense--elsewhere in Colossians, such as in Col 3:10, 3:12.30 In other words, although Col 2:11 speaks of the removal of the body of flesh in a figurative sense, it has in mind the literal removing of garments as part of the ritual of baptism.31 Likewise, απεκδυσαμεvoς in 2:15 may have both a the difficulties with this sort of evidence is the separation in time between Hippolytus (early 2nd century C.E.) and the composition of Colossians (perhaps 65-75 C.E.). The resemblance between the evidence offered below and Colossians will justify the comparison being made. 26 Hippolytus, Apost. Trad. 16-20, especially 17: "Let catechumens spend three years as hearers of the word." See also E. Glenn Hinson, The Evangelization of the Roman Empire (Macon, GA: Mercer Press, 1981), 73-85. 27 Hippolytus, Apost. Trad. 21:3, 11-12. 28 Hippolytus, ibid., 21:19-20. 29 For απεκδυω, απεκδυσις, and εκδυω, see A. Oepke, s.v. δυω, TDNT, 2:318-321. 30 See Oepke, s.v. εvδυω, ibid. 31 This interpretation appears to agree with that of Martin, who notes: "This [putting off the body of the flesh] is, at first glance, Paul's idiom for recalling the Christian's initiation to new life in Christ. The noun translated "putting off" (Gr. apekdysis) suggests a clean break with a past life, though the precise metaphor is one of disrobing and stripping off a set of clothes preparatory to taking on a fresh wardrobe (as in 3:9-10)"; Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon, 115. 7 figurative and a literal meaning in mind.32 Similarly, the use of εvδυω within 3:9-14 may refer both to the figurative putting on of Christ-like attributes, but also the putting on of clothes that follows baptism. Read this way, Col 2:11-15 (and perhaps many of the verses that follow, particularly 2:20-3:17) may be a baptismal sermon or exposition on the subject of baptism that has been incorporated into a letter that is primarily a refutation.33 If Col 2:11-15 has in mind the ritual of baptism, then what understanding of baptism does it assume? The key here is verse 12: "Having been buried with him in baptism, in which (or: in whom) you have been raised through faith in active power of God when he raised him from death." The passage assumed that in baptism the believer has somehow been buried with Christ, that is, he or she has participated in the burial of Christ. Although Romans 6 does refer to burial, there the emphasis is on death. Burial is emphasized in this passage because burial death; one might even argue that the burial of the believer in baptism with Christ causes the death of the believer. Similarly, the believer has through faith in the power of God (δια της πιστεως της εvεργειας τoυ θεoυ) been raised with Christ from the dead. The strength of the language (the use of [εv] αυτω/_, verbs compounded with συv-) suggests that the writer does not mean this is what baptism symbolizes, this is what baptism accomplishes. When we are baptized, we are buried (and are therefore dead) with Christ and we are raised with Christ. Beasley-Murray, in his discussion of the theology and practice of baptism in the NT, argues that there are three views present in Pauline discussions of baptism:34 1. in baptism we go through a death and resurrection like Jesus'; 2. the death and the resurrection of the baptized person is the death and resurrection of Jesus; 3. baptism involves a dying to sin and a rising to a new life (in the Spirit). All three views, Beasley-Murray maintains, are needed for a full appreciation for the Pauline witness to baptism. The second view is more evident in Col 2:11, where the believers are described as being circumcised in the circumcision of Christ. This metaphor has caused considerable difficulties for exegetes. Some see a polemic against the opponents, those who are seeking to impose rules and regulations on the Colossian church over and above what they already have in Christ, and we should indeed wonder why circumcision has been introduced at all if it was not at issue for the Colossians.35 If we assume that the opponents were insisting that Christians need to be circumcised, Col 2:11 says that in baptism we have already been, in effect, circumcised. An extension of this thought is that baptism is presented as the Christian equivalent of circumcision, and fulfills the same function as circumcision did for the Jews: it provides entry into the covenant community.36 Some see a reference 32 And if απεκδυσαμεvoς in Col 2:15 is closely parallel to the use of απεκδυσις in 2:11 (where the object is τoυ σωματoς της σαρκoς), then it raises again the question of who are the subject and object of απεκδυσαμεvoς. Is it God who strips, or Christ who divests himself of his body of flesh? If the latter, then Yates' translation and interpretation is strengthened. 33 On Colossians as a refutation, see Barth and Banke, Colossians, 42-43; 34 See Beasley-Murray, Baptism in the NT, 129-130. Note that by Pauline I mean letters written by Paul (such as Romans) and by those who maintained his tradition (such as Colossians). 35 White, "Colossians," 236. 36 See Harris, Colossians and Philemon, 102-103. 8 to the concept of spiritual circumcision (περιτoμη αχειρoπoιητω) that we find already in the Hebrew Bible (such as in Jer 4:4; 6:10; 9:25). Thus the circumcision of Christ is the spiritual circumcision that belongs to Christ and is accomplished by Christ.37 Finally, some argue that circumcision is a vivid metaphor for the death of Christ. Just as part of the (male) body is removed by circumcision, Christ gave up his entire body (σωματoς της σαρκoς) in his death on the cross. Circumcision is a "gruesome metaphor for the physical death of Christ."38 I suggest that rather than attempting to choose one interpretation to the exclusion of others, we should attempt to hold all possibilities together in creative tension.39 What do these possible interpretations taken together suggest? That baptism is where we are given the spiritual circumcision that comes only from Christ, an entry into the covenant people of God, such that we do not need any more rituals to be part of Christ and his church. But this spiritual circumcision came at a price: the violent and painful death of Christ on the cross. It involved not only a literal removal of clothes as part of a symbolic(?) ritual, it involved the painful removal of the body of flesh--the σαρξ, that part of our being which is subject to sinful desires and temptations. Baptism involves sacrifice and pain and death and burial. It is more than a symbolic rite, it is the point at which--according to this text--a person dies to her old nature (Rom 6:6), her sins are forgiven (Col 2:13), and she is raised to a new life. That new life is described well in Col 2:20 and following. Baptism, then, is not only the beginning of life in Christ. Baptism is the fundamental paradigm for Christian existence, and its effects last far longer than the time it takes to dry off. Baptist Christians would do well to reconsider the exposition of baptism that we find in Col 2:11-15. It is more than a symbol, and only the difficult, ambiguous, and metaphorical language of circumcision, stripping, burial, and rising again that we find in Col 2:11-15 could begin to do it justice. It is our entry into Christ, which the epistle to the Colossians portrays as supreme over every ruler and authority, over every human made philosophy and regulation. 37 Lohse, Colossians and Philemon, 102-104. 38 O'Brien, Colossians, Philemon, 116-117; Beasley-Murray, Baptism in the NT, 157-160. 39 Martin is particularly effective at attempting to hold together the different interpretations of this verse; idem, Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon, 115-116. 9 Bibliography Barth, Marcus, and Helmut Blanke. Colossians: A New Translation With Introduction and Commentary. Translated by Astrid B. Beck. Anchor Bible Commentary, vol. 34B. New York: Doubleday, 1994. A through and detailed commentary on the epistle to the Colossian church. Particularly sensitive to how certain words and images are used elsewhere in the Bible, including the LXX. Bauer, Walter, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 2nd ed., revised and augmented. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979. An indispensable resource for the preliminary translation of New Testament passages. Beasley-Murray, G. R. Baptism in the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1962. An excellent discussion of the origins, practice, and theology of baptism in the New Testament. Beasley-Murray discusses several different passages with respect to the issue of baptism, paying particular attention to the diversity of perspectives that can be found within the New Testament. Easton, Burton Scott, trans. The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1934. An early 2nd century C.E. text which contains one of the earliest descriptions of the ritual of baptism as practiced within the early church outside of the New Testament. Harris, Murray J. Colossians and Philemon. Exegetical Guide to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991. A commentary that focuses on the Greek text, often useful for listing all the possible translations and interpretations of a particular word or phrase. Hinson, E. Glenn. The Evangelization of the Roman Empire: Identity and Adaptability. Macon, GA: Mercer Press, 1981. A detailed and thorough overview of the early church with particular attention to its institutions. Includes a survey of the early practice of baptism and how baptism was understood by the early church during the first several centuries C.E. Johnson, Luke T. The Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1986. A useful survey of the background(s) and books of the New Testament, including an overview and introduction to the epistle to the Colossian church. Kittel, Gerhard, ed. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Translated and edited by Geoffrey Bromiley. 11 volumes. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964-. An extraordinarily useful resource for the further detailed studies of words in the Greek New Testament, including descriptions of the history of their usage in biblical, classical, extra-biblical, and post-biblical literature. Particularly useful for comparison the different usages of a particular word in different contexts. 10 Lohse, Eduard. Colossians and Philemon. Translated by William Poehlmann and Robert Karris. Hermeneia. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1971. A detailed and thorough commentary on the text of Colossians. Particularly useful for references to other scholarly literature. Martin, Ralph P. Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon. Interpretation. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1991. A less technical commentary on the epistle to the Colossian church that is particularly strong with respect to theological and expository issues surrounding the text. O'Brien, Peter T. Colossians, Philemon. Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 44. Waco, TX: Word Books, 1982. A thorough and detailed commentary on Colossians that attempts to pay particular attention to the movement of thought in each passage. Stagg, Frank. "Colossians." In Mercer Commentary on the Bible, edited by Watson Mills and Richard Wilson, 1235-1239. A brief introduction and commentary on the epistle to the Colossian church. Of limited usefulness due to its brevity. Schnackenburg, Rudolf. Baptism in the Thought of St. Paul. Translated by G. R. Beasley-Murray. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1964. A thorough and excellent analysis of Pauline passages which deal with the issue of baptism, and how the Pauline view(s) of baptism fit in the context of Pauline theology as a whole. White, R. E. O. "Colossians." In Broadman Bible Commentary, vol. 11. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1971. A moderately brief introduction to and commentary on the epistle to the Colossian church. Attempts well to break the epistle down into manageable passages and thought units. Yates, Roy. "Col 2,14: Metaphor of Forgiveness." Biblica 71 (1990): 248-259. An excellent survey of previous translations and interpretations of Col 2:14, it offers a particular solution to grammatical and interpretive problems posed by the verse. ________. "Colossians 2.15: Christ Triumphant." New Testament Studies 37 (1991): 573-591. An excellent overview of various interpretations and translations of Col 2:15, it offers and argues for a particular approach to this verse. 11