File

advertisement

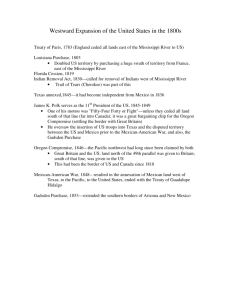

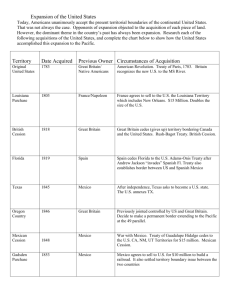

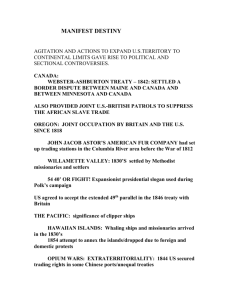

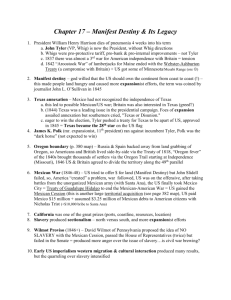

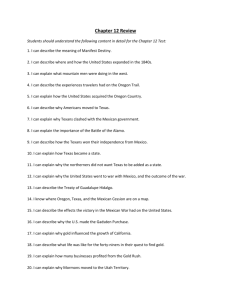

Manifest Destiny How our country got its shape :) Although British hopes of winning the Revolutionary War ended in 1781 with their defeat at Yorktown, nearly two years passed before the United States and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris and officially ended the war. The peace process was complicated because France, Spain, and Holland had also joined the conflict, fighting with the Americans against the British. Each of these countries had their own strategic national goals for the war, which made a final peace harder to agree on. Also, although Britain’s King George III did not think he could win the war anymore, he was still determined not to grant the Americans independence. But, John Adams, John Jay, and Benjamin Franklin, the three Americans sent to Britain to negotiate the peace treaty, insisted that independence for the colonies be built into the peace agreement. The Treaty of Paris was finally ratified in September 1783, and it was a great victory for the Americans. The treaty not only recognized the United States of America as an independent nation, but also established boundaries that extended far to the west of the 13 original colonies. The new country would be bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the east, the Mississippi River on the west, Florida on the south, and Canada and the Great Lakes on the North. Spain retained control of Florida, and the United States was permitted use of the Mississippi River. As the map shows, much of the land granted to the United States in the treaty did not belong to any of the 13 original states. For a time, some of the original states tried to claim these new lands as their own. For instance, New York tried to claim lands that that included present-day Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. North Carolina tried to claim portions of what is now Tennessee, while Virginia tried to claim land that is now part of Michigan. Stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border, the enormous Louisiana territory was originally settled by the French in the early 18th century. In 1802, France stopped allowing U.S. merchants to use the city of New Orleans, an important commercial city located at the base of the Mississippi River, to ship their goods. President Thomas Jefferson was concerned about this situation and sent James Monroe to Paris to try to help Robert Livingston, the American minister to France, negotiate a deal. Jefferson, Monroe, and Livingston hoped to be able to purchase a small amount of the territory - possibly a section as small as just the eastern half of New Orleans - so that American merchants could continue to use the river to transport their goods. However, as Monroe arrived in Paris, France was on the brink of war with Britain. It was also fighting a losing battle against a slave uprising on the island of Hispaniola (the portion of the island that is now Haiti) in the Caribbean Sea. Unable to send adequate troops to defend the territory from Britain, France decided to make the Americans a surprising offer. Monroe and Livingston were astonished when the French minister offered to sell America all 828,000 square miles of the Louisiana Territory for the price of $15 million. The Americans jumped at the offer, and on April 30, 1803, the deal was finalized. The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the country at a cost of approximately four cents an acre. It met with overwhelming approval by Americans eager to expand the borders of their new country. Fifteen states, among them Louisiana, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Colorado, and Nebraska later developed either entirely or partly from the land gained in the purchase. The United States signed the Convention of 1818 with Great Britain in order to settle some issues left open by the Treaty of Ghent, which four years earlier had ended the War of 1812. The new treaty stated that Britain and the United States would jointly occupy Oregon Territory (an arrangement that lasted until 1846), and clarified the northern border of the Louisiana Purchase. The land acquired by the United States in the treaty, known as the Red River Basin, would ultimately become part of the states of Minnesota and North Dakota. Although Spain, France, and Britain all held Florida (or parts of it) prior to the American Revolution, by the end of the war, it was Spanish territory. However, the location of the border between the United States and Spanish territory remained an issue of dispute between the two countries. The American acquisition of Florida actually occurred in small steps. Americans had long settled the territory, and throughout the early years of the 19th century American settlers in Florida periodically rebelled against Spanish authorities, sometimes with the support of American officials. Moreover, the use of the region as a safe haven for runaway slaves, as well as ongoing Native American hostilities, also gave American authorities "justifications" for contesting Spanish sovereignty in Florida. In 1814 and then again in 1817-1818, future American president Andrew Jackson led frontier forces in defeating and removing various Native American tribes indigenous to the region, even as Spain retained official control there. At this point, the United States and Spain had to either fight or negotiate over which country would retain possession of Florida. At the same time, Spain was dealing with serious problems with its other colonies. Thus, neither side wanted war, and in 1819, the two countries signed the Adams-Onís Treaty. The treaty, named after Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and Spanish minister Louis de Onís, ceded Florida to the United States. In exchange, the United States agreed to pay up to $5 million in damages to Americans who had claims against Spain and to forfeit any claims to Texas. Texas War for Independence The Spanish were the first to colonize the states that today make up the American southwest, including the state of Texas. In the waning years of the Spanish empire, in the early 19th century, Spain decided to allow some Americans to settle in Texas. In 1821, Moses Austin obtained permission to lead a group of 300 American families in creating a new settlement there. After his death, his son Stephen Austin, took over the plan and secured permission - this time from the newly independent Mexican government - to proceed with the settlement. By 1835, approximately 20,000 American, Mexican, and European settlers had arrived in Texas, bringing with them an additional 4,000 slaves. The Mexican government attempted to limit the influx of American immigrants, to no avail. In 1835, fighting broke out between the Mexican Army and AngloAmerican colonists who were angry with the Mexican government for attempting to limit the practice of slavery and for violating the Mexican constitution. In 1836, they declared Texas an independent state, called the Republic of Texas. After a decisive Texan victory at the Battle of San Jacinto later that year, fighting stopped. The Mexican government, however, never recognized the new state, and for the next decade, the Lone Star Republic had a shaky existence. It was under constant threat of invasion from Mexico, and the government did not have enough money in its treasury to work effectively. In 1845, the Republic of Texas voluntarily asked to become a part of the United States, and the government of the United States agreed to annex the nation. Mexican leaders had long warned the United States that if it tried to make Texas a state, it would declare war. And, almost immediately after Texas joined the Union, the United States and Mexico went to war about where the proper border for the state of Texas should be. This was called the Mexican-American War. The Republic of Texas included the present-day state of Texas as well as portions of New Mexico, Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming. Oregon Country was a portion of land between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains in the northwest portion of the present-day United States. In 1818, the United States and Britain agreed to a "joint occupation" of Oregon, allowing citizens of both countries to settle there. Over the next several decades, American and British settlers came to Oregon for different reasons. The British came mostly for the fur trade, while Americans came to be missionaries or to start farms or larger settlements. By the 1840s, Americans outnumbered their British compatriots, and the fur trade was no longer as lucrative as it had once been. American expansionists - among them President James Polk - were increasingly looking to end the joint occupation and claim Oregon for America alone. Finding themselves in a weakened position, the British agreed to negotiate. Negotiations between the United States and Britain over the Oregon Country began in the summer of 1845. Because any states that would eventually be formed out to the territory would be free states, anti-slavery Northerners were strongly in favor of acquiring as much of the territory as possible. America's first proposal was that the territory be divided roughly in half, with the boundary drawn at the 49th parallel. When the British rejected this offer, expansionist Northerners called for greater American aggression, using the slogan "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!" (Fifty-four Forty referred to the latitude line marking the northernmost boundary of the territory.) Pro-slavery Souhtern Congressmen, however, made it clear that they would not support a war with Britain over the territory. Britain did not want to go to war over the issue either, and in 1846, the two countries reached an agreement to divide the territory at the 49th parallel. Oregon Country would later become the modern-day states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, as well as portions of Montana and Wyoming. After Texas joined the United States in 1846, a boundary dispute broke out almost immediately between the United States and Mexico, the country from which Texas had won its independence a decade earlier. The U.S. said the southern boundary of the state should be the Rio Grande, which was further south of the original boundary set by the Nueces River. On April 25, 1846, after the U.S. cavalry ignored an order from the Mexican army to retreat to the Nueces River and instead advanced south to the Rio Grande, fighting broke out. Three weeks later, Congress declared war on Mexico. Fighting continued for more than a year, and ended in September 1847. In February 1848, the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. The treaty recognized Texas as a U.S. state, and ceded a large chunk of land about half the area that belonged to the Mexican republic - to the United States for the cost of $15 million. The Mexican Cession included land that would later become California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as portions of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. The treaty also stated that Mexicans who remained in the state would be permitted to become U.S. citizens, and that they would be allowed to keep their property. However, the treaty was never fully honored. In the decades following the signing of the treaty, MexicanAmericans were stripped of nearly 20 million acres of their land by American businessmen, ranchers, and railroad companies, as well as by the U.S. Department of Interior and Department of Agriculure. The Treaty of Gadalupe Hidalgo had described the U.S.-Mexico boundary vaguely, and following the MexicanAmerican War, the United States and Mexico continued to dispute the border between the two countries. The addition of new American territories granted by the Treaty of GuadalupeHidalgo was driving western development, and there were rival plans to build railroads to the west coast. One plan called for routing a rail line through disputed Mexican territory south of the Gil River. In 1853, President Franklin Pierce sent James Gadsden to negotiate with Mexico. Gadsden was president of the South Carolina Railroad and a former military officer who had been involved in the forcible removal of Seminole Indians in Florida. The Mexican governemnt was in desperate need of money, and it agreed to sell a small strip of land along the U.S.-Mexico border to the United States for $10 million. Eventually the Southern Pacific Railroad built a line to California that crossed the territory. The Gadsden Purchase included land in present-day Arizona and New Mexico. Russian explorers first reached the land that would eventually become the state of Alaska in the 17th century. For several centuries, Russia continued to occupy the territory. The Crimean War of the mid-19th century, however, convinced the Czarist Russian government that it could not defend the territory in case of another war with Britain. (Britain had shown signs of interest in Alaska as an extension of its territory in present-day Canada.) Although the Russian government did not want to lose Alaska, it thought it would be better to receive compensation for the territory from an ally than lose it in battle to an enemy. In 1867, Secretary of State William H. Seward met with Russian diplomats and,after an all-night negotiating session that ended at 4 a.m.,arranged for the United States to purchase Alaska for the cost of $7.2 million - about two cents an acre. At the time, the purchase was widely unpopular among Americans, partly because President Andrew Johnson was himself suffering from very low approval. Critics of the purchase derided Alaska as "Seward's Folly" or "Andrew Johnson's Polar Bear Garden," arguing that it was ridiculous to purchase land so far away from the rest of the United States. American attitudes quickly changed, however, with the discovery of gold in Alaska in the 1890s. In 1959, nearly one hundred years after it became an American territory, Alaska became the 49th state of the United States. Throughout the 19th century, Britain, France, and the United States all showed special interest in the independent island nation of Hawaii. The three nations competed with each other to gain special trading priveleges there. Towards the end of the century, however, American sugar plantation owners came to increasingly dominate the Hawaiian economy. These wealthy planters wanted Hawaii to become a part of the United States, so they could sell the sugar that they raised to Americans without worrying about the U.S. government imposing a tariff (or tax on imported goods). A tariff would make their sugar more expensive for American consumers, and thus would have decreased the planters' profits. When the Hawaiian leader, Queen Liluokalani, sensed a threat from the increasing power held by the American planters, she tried to strenthen the monarchial government. In response, in 1893 a group of American planters led by Samuel Dole organized a coup and deposed her. In 1894, Dole sent a delegation to Washington, D.C., to ask the United States to annex Hawaii, but President Grover Cleveland opposed annexation and argued that the queen should be restored. Dole then declared Hawaii an independent republic. In 1898, a new president, William McKinley, came to office and agreed to annex the islands. Hawaii became the 50th state of the Union in 1959.