The Rhetorical Triangle: Understanding and Using

advertisement

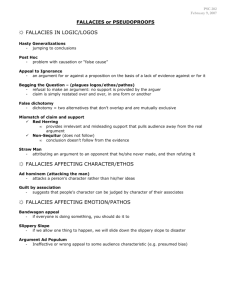

The Rhetorical Triangle: Understanding and Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos Environmental Science and Technology HS Background • Aristotle taught that a speaker’s ability to persuade an audience is based on how well the speaker appeals to that audience in three different areas: logos, ethos, and pathos. Considered together, these appeals form what later rhetoricians have called the rhetorical triangle. Balance and Purpose The rhetorical triangle is typically represented by an equilateral triangle, suggesting that logos, ethos, and pathos should be balanced within a text. However, which aspect(s) of the rhetorical triangle you favor in your writing depends on both the audience and the purpose of that writing. Yet, if you are in doubt, seek a balance among all three elements. Definitions • Logos appeals to reason. Logos can also be thought of as the text of the argument, as well as how well a writer has argued his/her point. • Ethos appeals to the writer’s character. Ethos can also be thought of as the role of the writer in the argument, and how credible his/her argument is. • Pathos appeals to the emotions and the sympathetic imagination, as well as to beliefs and values. Pathos can also be thought of as the role of the audience in the argument. Logos: Appeals to Reason or Logic DOs: Evidence Reasons Opinions Examples Facts Data Grounds Proof Premise Statistics Explanations Information DON’Ts (Fallacies): • Begging the question • Red herring • Straw man • Post hoc • Hasty generalization Premise and Conclusion • Premises are statements of (assumed) fact which are supposed to set forth the reasons and/or evidence for believing a claim. • The claim, in turn, is the conclusion • 1. Doctors earn a lot of money. (premise) 2. I want to earn a lot of money. (premise) 3. I should become a doctor. (conclusion) Ethos: Credibility of the Writer DOs: Be knowledgeable about your issue by - Examples - Personal experience - Statistics - Empirical data Be fair - Demonstrate fairness and courtesy - Empathize with other points of view Build a bridge to your Audience - Ground your argument in shares values (See warrants, assumptions, widely held values, general principles, etc.) DON’Ts (Fallacies): • Ad hominem • Authority instead of evidence Pathos: Appeals to Emotion DOs: DON’Ts (Fallacies): • Use concrete language • Use specific examples and illustrations • Provide evidence • Give presence and emotional resonance • Use narratives • Use images, comparisons and analogies • Bandwagon appeal • Slippery slope Guiding Questions The following questions can be used in two ways, both to think about how you are using logos, ethos, and pathos in your writing, and also to assess how other writers use them in their writing. Logos: Is the thesis clear and specific? Is the thesis supported by strong reasons and credible evidence? Is the argument logical and arranged in a wellreasoned order? Guiding Questions Ethos: • What are the writer’s qualifications? How has the writer connected him/herself to the topic being discussed? • Does the writer demonstrate respect for multiple viewpoints by using sources in the text? • Are sources credible? Are sources documented appropriately? • Does the writer use a tone that is suitable for the audience/purpose? Is the diction (word choice) used appropriate for the audience/purpose? • Is the document presented in a polished and professional manner? Guiding Questions Ethos: • What are the writer’s qualifications? How has the writer connected him/herself to the topic being discussed? • Does the writer demonstrate respect for multiple viewpoints by using sources in the text? • Are sources credible? Are sources documented appropriately? • Does the writer use a tone that is suitable for the audience/purpose? Is the diction (word choice) used appropriate for the audience/purpose? • Is the document presented in a polished and professional manner? Final Thoughts • While the previous information presents logos, ethos, and pathos in as separate elements in writing, it is important to remember that sometimes a particular aspect of a text will represent more than one of these appeals. • For example, using credible sources could be considered both logos and ethos, as the sources help support the logic or reasoning of the text, and they also help portray the writer as thoughtful and engaged with the topic. This overlap reminds us how these appeals work together to create effective argumentative writing. Fallacies in Argument A fallacy is a common error in reasoning which people often fail to notice in their own arguments or which others may use in their arguments in the hope that we won't notice them. Fallacies in Argument A fallacy is a common error in reasoning which people often fail to notice in their own arguments or which others may use in their arguments in the hope that we won't notice them. Begging the Question • An argument that begs the question asks the reader to simply accept the conclusion without providing real evidence; the argument either relies on a premise that says the same thing as the conclusion (which you might hear referred to as "being circular" or "circular reasoning"), or simply ignores an important (but questionable) assumption that the argument rests on. Red Herring • Partway through an argument, the arguer goes off on a tangent, raising a side issue that distracts the audience from what's really at stake. Often, the arguer never returns to the original issue. Straw Man • One way of making our own arguments stronger is to anticipate and respond in advance to the arguments that an opponent might make. • In the straw man fallacy, the arguer sets up a weak version of the opponent's position and tries to score points by knocking it down. • However, just as being able to knock down a straw man (like a scarecrow) isn't very impressive, defeating a watered-down version of your opponent's argument isn't very impressive either. Post Hoc (False Cause) • Assuming that because B comes after A, A caused B. Of course, sometimes one event really does cause another one that comes later—for example, if I register for a class, and my name later appears on the roll, it's true that the first event caused the one that came later. • However, sometimes two events that seem related in time aren't really related as cause and event. • That is, correlation isn't the same thing as causation. Hasty Generalization • Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate , atypical , or too small. Fallacies ETHOS Ad Hominem • The arguer focuses our attention on people rather than on arguments or evidence. • The arguer attacks his or her opponent instead of the opponent's argument. Appeal to Authority • Often we add strength to our arguments by referring to respected sources or authorities and explaining their positions on the issues we're discussing. • If, however, we try to get readers to agree with us simply by impressing them with a famous name or by appealing to a supposed authority who really isn't much of an expert, we commit the fallacy of appeal to authority. Fallacies PATHOS Fallacies PATHOS Slippery Slope • The arguer claims that a sort of chain reaction, usually ending in some dire consequence, will take place, but there's really not enough evidence for that assumption. • The arguer asserts that if we take even one step onto the "slippery slope," we will end up sliding all the way to the bottom; he or she assumes we can't stop partway down the hill. Critique: Fallacies in Argument For each of the 9 arguments: On the handout: 1. Identify the premise and conclusion. LABEL each of these on the handout. 2. Identify what the arguer was attempting to appeal to (logos, ethos, pathos). LABEL each argument on the handout. 3. Identify the fallacy that the writer committed on the handout. LABEL each argument on the handout. On a piece of lined paper (1 paper for you and your partner) 1. Write a paragraph that provides a rationale for your choice on a lined piece of paper – Topic Sentence: State the fallacy – Evidence: Refer to specific points of the argument to prove why the argument is the fallacy that you selected. – Link: Explain why the arguer is guilty of the fallacy. – Concluding Sentence: Synthesis Example #8- Begging the Question "Active euthanasia is morally acceptable. It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death." • Logos • Premise: It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death. • Conclusion: Active euthanasia is morally acceptable Rationale- Begging the Question Topic Sentence: The arguer hasn't yet given us any real reasons why euthanasia is acceptable; instead, her argument "begs" (that is, evades) the real question. Evidence and Link: If we "translate" the premise, we'll see that the arguer has really just said the same thing twice: "decent, ethical" means pretty much the same thing as "morally acceptable," and "help another human being escape suffering through death" means something pretty similar to "active euthanasia.” The premise basically says, "active euthanasia is morally acceptable," just like the conclusion does. Concluding Sentence: The arguer has not provided the audience with any reasons, evidence, and is redundant. The audience is left with no answers.