Educational-Leadership-Article

advertisement

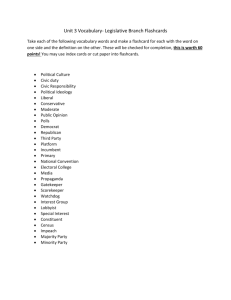

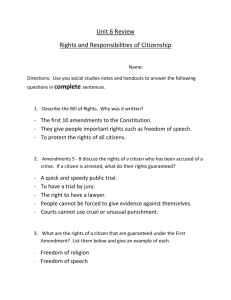

Educational Leadership This is an essay about using technology to prepare students for civic life. A rich democratic education requires that students have opportunities to engage in dialogue within diverse communities, representing the full variation of our multicultural and economically-stratified society. As America’s neighborhoods and schools become rapidly resegregated and increasingly homogenous, online spaces are an increasingly important forum for students to have meaningful interaction with other young people from different backgrounds and life circumstances. Putting Technology in the Service of Learning There are thousands of schools and districts across the country in the midst of researching what devices they should buy to create their technology infrastructure, and nearly all of them should stop. Stop debating Mac vs. PC, stop debating tablet vs. laptop, stop debating projectors vs. interactive whiteboards. For technology to be a worthwhile investment in a school, technology needs to be in the service of learning goals. Most schools don’t have a clear vision of what they want students to learn—or of who they want children to be—after 4 or 6 or 12 years. In many of the schools and districts where debates about this hardware versus that hardware are taking place, there is no clear sense of why anyone should buy all of this technology in the first place. In a democratic society, the best schools aim for three kinds of goals: readying students for working life, for inner life, and for civic life. In our era of economic stagnation, global competition, and widening inequality, the discourse of education reform mostly centers on preparing students for the labor market, having them “college- and career-ready” in our current parlance. Preparing students for meaningful work is an important part of a great education, but it is not the sum total of one. Schools should also prepare students for a reflective life: to appreciate music, dance, sports, theatre, and the arts; to find hobbies or pursuits that spark curiosity and enjoyment; to employ habits and tools of moral reflection. Finally, students should leave school wellequipped to participate in the civic sphere: to contribute to their community, to make their voice heard in democratic deliberations, to have the disposition and skill set to take effective civic action. Yogi Berra had a quip for schools that have invested extensively in technology infrastructure without thinking deeply about the purposes of education: “We’re lost, but we’re making great time!” I came to an interest in educational technology by way of the history classroom. Like many history teachers, I view my vocational calling not as a cog in a 12 year college- and job- placement program, but as preparing students for their roles and responsibilities in a democratic society. If you believe, as I do, that education is the bulwark of our democracy, then it follows that schools making substantial investments in technology ought to be considering how those investments support schools as training grounds for citizens. Civic Education in a Demographically Isolated Society Political theorists, going as far back as John Stuart Mill and John Dewey, have long argued that exposure to diverse perspectives is vital both a robust civil society and to the development of individuals within those societies. Engaging in democratic discourse requires engaging with people who take different perspectives on issues, and differing perspectives are often a function of different backgrounds, upbringings, and life circumstances. Effective civic learning environments encourage students to encounter people with different ideas and beliefs. Therefore, one of the greatest threats to civic education in America today is demographic: our schools and neighborhoods are increasingly re-segregated by both race and class. In urban centers, decades of integration work have been rolled backwards, and in suburban and rural areas, students increasingly find themselves living in homogenous neighborhoods. The harms from these trends are raising alarms from across the political spectrum. From the right, libertarian political scientist Charles Murray recently published the book Coming Apart describing how upper class white Americans have created their own residential enclaves separating them from working class white Americans. Murray argues that these class divisions threaten the fabric of a unitary nation. On the left, education scholar Gary Orfield has long documented the re-segregation of American schools, and his most recent 2012 report E Pluribus… Separation shows that racial segregration continues to grow and so-called “double segregation,” segregation by both minority status and poverty level, also continues to expand. These divisions between neighborhoods are aggravated by tracking practices within schools. In many schools, whatever diversity remains after residential sorting is further homogenized by assigning students into classes by measures of academic achievement. Since academic achievement is highly correlated with family income, dividing students into basic, college prep, and honors tracks creates situations where, even in demographically diverse schools, students experience classrooms filled with students from similar backgrounds. Here then, we come to the nub of a critical problem in the civic mission of schools: If we know that meaningful civic education requires having students engage with peers holding diverse perspectives, how can we encourage dialogue across difference in the face of these stark and growing demographic divides? One answer involves creating online spaces where diverse students can convene and learn together. Creating Online Spaces for Dialogues across Difference FACING HISTORY DIGITAL MEDIA INNOVATION NETWORK There are many fabulous examples of online projects that bring together students in communities that bridge geographic differences. I’ll present two of these examples, Facing History and Ourselves’s Digital Media Innovation Network and the Flat Classroom Project, and then explain some of the important design principles that animate these networks. I’ll end with a short discussion of how educators can get their students involved in these projects. Facing History and Ourselves is an organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote a more humane and informed citizenry. In that spirit, in 2010, Facing History launched the Digital Media Innovation Network (DMIN), a project designed to bring together learners and educators from around the world to nurture media literacy, perspective-taking skills, and related civic competencies. The first DMIN project involved 14 schools from across the country and around the world, from Boston and Oakland to Cape Town and Shanghai. Educators and students engaged in an investigation of Nicolas Kristof’s documentary Reporter, a film exploring the challenges of highlighting international stories of injustice and tragedy in an age of major shifts in the media landscape. Students watched and examined the documentary, and they then worked independently in their own classrooms to create digital mini-documentaries showcasing their lives, their communities, and their aspirations. Afterwards, students came together in an online network to discuss Reporter, share their documentaries, and engage in conversations about identity, storytelling, and the future of media and journalism. Several features of the design of the project are worth noting. Facing History worked deliberately to choose classroom partners with geographic, cultural, and ethnic diversity, so that students could have a true dialogue across difference. Teachers received both shared training as well as opportunities to connect and socialize in advance of the project, so the connections among teachers could scaffold communication across classrooms. Finally, the content of the course was chosen to have broad resonance for teens, choosing a powerful documentary about the relationship between changing media and age-old human suffering and student-produced works about teens’ own lives. Facing History conducted an evaluation of the program, and one of the central themes that emerged involved students recognition of the foreign and the familiar. In discussing Reporter, students shared a human repulsion to the terrible situation in the Congo, but they also had different perspectives on how to interpret the problem, the actors, and potential solutions. In reacting to the mini-documentaries, students found similar themes of adolescence in their diverse stories while appreciating the wide differences in people’s experiences. As one girl wrote in a reflection, “The most surprising thing that I learned with this project is that there are also other students and teachers that are just like we are. They might not be in the same place as we are in and they might have totally different lives that we do but we are all making a difference in our classes that can hopefully move the world.” This kind of perspective-taking, of recognizing the shared humanity of diverse peoples (and shared adolescent angst of diverse teenagers), is at the heart of developing civic and participatory skills in young people. Flat Classroom Project The Flat Classroom Project, founded by classroom teachers Vicki Davis and Julie Lindsay, provides another vehicle for these kinds of international exchanges. Like the DMIN project, the Flat Classroom Project organizes classrooms of students from across the world into project teams to explore the “world flatteners” described in Thomas Friedman’s The World is Flat. The Flat Classroom Project goes one step beyond the Facing History DMIN project in terms of student collaboration by putting students from different classrooms around the globe into international working groups. Teams made up of students from different countries work together over a period of weeks to create web pages and digital videos describing an assigned dimension from Friedman’s book. Thus, students from around the world use new media to discuss and describe the technology and social trends that are transforming their world. As with the DMIN project, the Flat Classroom Project is carefully structured to facilitate learning and exchange. Before the project period, teachers engage in training and conversation before student involvement, to build a foundation of shared understanding. Then students engage in a deliberately crafted “handshake” period, where students introduce themselves to teammates, and engage in community building before engaging in academic work. Students then build their digital products together, with the support of peer and expert reviewers. Participants face the challenges of language barriers and ansynchronous collaboration, and the opportunity to work with and learn from young people from around the globe. FCP RESEARCH HERE/ STUFF FROM BOOK? Joining and Creating Collaborative Online Projects Both the DMIN project and the Flat Classroom Project Practices Intentionally solicit diversity Have projects stretch over long enough periods of time for involvement from schools with technology projects Choosing content with broad resonance Allow students to share through multiple media Provide teachers with training and ongoing support and focused on Nicolas Kristof’s documentary film Reporter. Teachers received extensive training on media literacy, media production, and online collaborative practice. They then worked intensively with their students to create digital projects, and they brought their students into a global online community to share their work with their online peers. Students watched Reporter, engaged in discussions, and shared their own mini-documentaries showcasing their lives, their communities, and their aspirations. Practices within schools aggravate the divisions between schools. Emerging technologies have the potential to support a wide variety of civic learning aims; a partial list could include allowing students to produce civic media, to track and participate in civic actions, to analyze political campaigns and media, and to engage in immersive simulations of political processes. In the spirit of putting technology in the service of learning, rather than starting from what technology can do, I want to begin One of the most promising roles for technology to support civic learning is closely tied to one of the most troubling phenomena in America: the increasing re-segregation of our schools. The stark divides One of the most troubling demographic phenomena in the United States is the re-segregation of American schools. In urban centers, decades of integration work have been rolled backwards, and in suburban and rural areas, students increasingly find themselves living in homogenous neighborhoods (Orfield & Lee, 2005) . Political theorists going back to John Stuart Mill and John Dewey have argued that Classrooms are further homogenized through tracking practices (Oakes, 2005). Developing robust civic competencies requires that students learn how to communicate and collaborate across ethnic and class differences (Kahne, Middaugh, Lee, & Feezell, 2012) , and demographic isolation inhibits this development. Emerging technologies have A critical part Interpreting and Creating Political Media For me, it is not enough to ask “will technology get students ‘engaged’?” or “will technology help prepare students for college?” In my first year of classroom teaching, now ten years ago, I was asked to teach World History to high school freshman. I was also told that a cart of laptops sat in the back corner of my classroom, and I should have my students use them every day as part of a pilot program. Eventually, in this essay, I’m going to describe a variety of ways that technology can create opportunities for students to engage in “dialogue across difference,” to make a human connection with people across the city, across the country, across the world, and across time, with people who have different beliefs, perspectives, ideas, and ideals. Eventually, I’ll talk about specific tools, specific programs, specific strategies for creating or joining these kinds of community dialogues. This argument, however, requires a bit of preface. Discussions of education technology should lead with the education part and not the technology. We have plenty of examples of how might help There are plenty of resources for those interested in exploring how Generating Discourse Across Difference Let me put forth three kinds of goals for student s My general sense, The most commonly discussed purposes are to prepare students economically, serving as a gateway to post-secondary education and employment, helping students leave. Online communities and networks are one of the most powerful tools that educators have to counteract these alarming trends. Online spaces allow students in homogenous learning spaces to engage with students from widely different life circumstances. Moreover, online platforms allow students to participate in dialogue across difference using the same media practices that are reshaping the civic sphere and defining this generation (Reich, 2008). This chapter will examine a case study of the Digital Media and Innovation Network (DMIN), a network of educators and students facilitated by Facing History and Ourselves. Facing History is an organization whose mission is to engage students of diverse backgrounds in an examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism in order to promote a more humane and informed citizenry (Barr & Bardige, 2012) . In that spirit, DMIN is designed to bring together learners and educators from around the world to nurture media literacy, perspective-taking skills, and related civic competencies. The first DMIN project, conducted in 2010, involved 15 schools from around the world, and focused on Nicolas Kristof’s documentary film Reporter. Teachers received extensive training on media literacy, media production, and online collaborative practice. They then worked intensively with their students to create digital projects, and they brought their students into a global online community to share their work with their online peers. Students watched Reporter, engaged in discussions, and shared their own mini-documentaries showcasing their lives, their communities, and their aspirations. In this chapter, we will examine the inaugural DMIN project through the lens of design research (Dede, 2005). Design research is a method commonly used in the learning sciences and for the study of innovative education technology practices where effective pedagogical practices are not well developed. The DMIN project was developed with a series of design principles reflecting both Facing History’s core pedagogical stances as well as our strategies for adapting those core stances for online environments. The project was rigorously assessed by our evaluation team (internal to the organization, but independent from the DMIN leaders), allowing for iterative improvements to our learning designs from one DMIN project to the next. To explicate this case, we will first articulate the key rationales behind our 2010 DMIN project and define the principles that informed the learning design of our network. We will then provide formative evaluation data showing initial evidence of DMIN’s impact on students’ competencies (such as media literacy skills) and dispositions (such as perspective taking and openness to difference) (Romer & Mingo, 2011a; Romer & Mingo, 2011b) . In particular, students involved in the DMIN project expressed a deepened respect for both the differences that emerged in the diverse online community and the values that were shared across these geographic and social divides. We will conclude with an assessment of the vital role that online communities will play in nurturing civic competencies in the years to come.