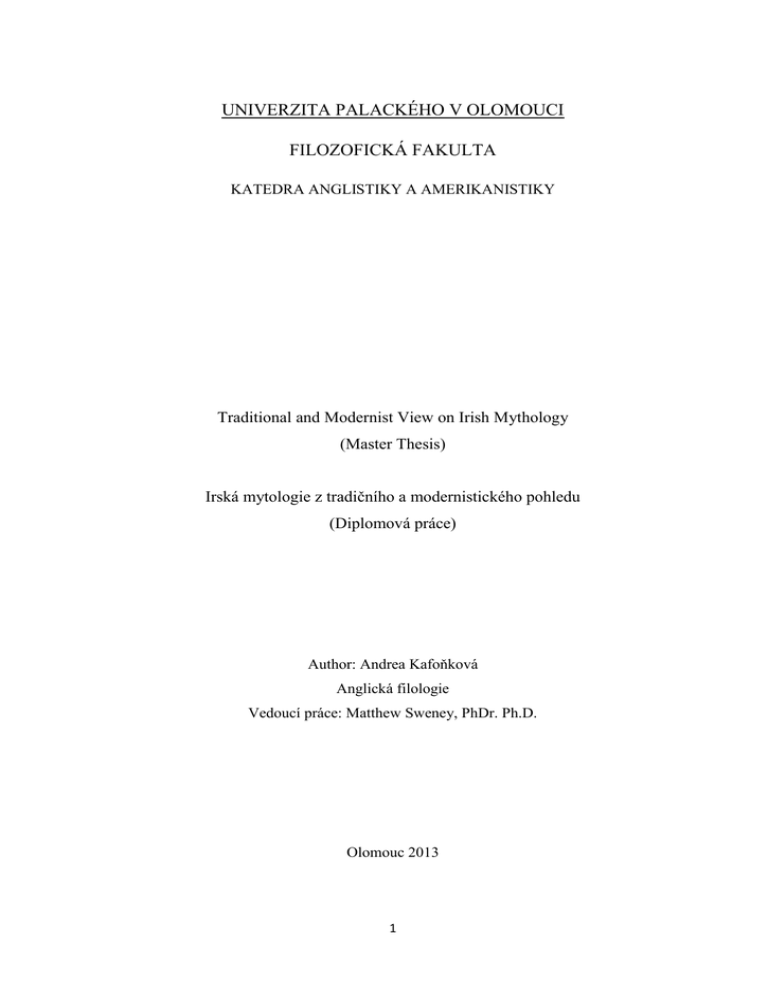

1. Traditional View on Irish Mythology

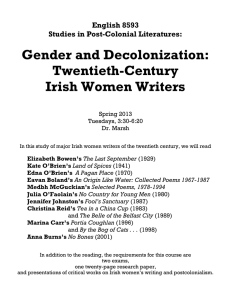

advertisement