MORPHOLOGY= The study of shapes - Mersin University Linguistics

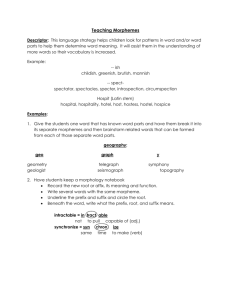

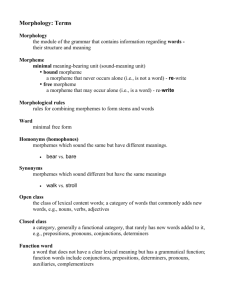

advertisement

Morpheme: -Abstraction of the various types of morphs - Smallest unit of a language that convey some kind of information -s in cat/ cats -z in dog/ dogs -es in dish/ dishes -en in ox/ oxen Zero morph in sheep/ sheep Vowel change in foot/ feet Convey the same information which also happens in allomorphs Free morpheme: stands alone as its own word Bound morpheme: needs some kind of host to attach to He will go home tomorrow -> only free morphemes The oxen pulled the chart-> 2 bound morphemes in oxen /–en/ and pulled /-ed/ Root: the smallest unit with any semantic content Unhappiness -> happy Perfectly -> perfect Stem: - base for an inflected word form - can consist minimally of a root but may also a modification of the root in some ways Example 1: the stem horsehair is a compound of two roots: horse + hair This stem can me modified for plural to form: horsehairs Example 2: if we add –er to the root teach we get the stem teacher The root and stem carry lexemic information which is the basic semantic information of the word. Example: -The lexeme of work, works, worked, working is WORK -The lexeme of hair, hairs is HAIR -The lexeme of horsehair and horsehairs is HORSEHAIR An obligatorily bound morpheme which does not carry any lexemic information Affixes can be derivational or inflectional Derivational affixes create new words like unand –ness in unhappiness İnflectional affixes carry grammatical information such as plural –s or the past tense –ed and do not change the meaning of the word Prefix: attaches to the beginning of a host word Derivational prefix; un- in unhappy İnflectional prefix: the language Logba okpe – inashina o-kpe – i-nashina 3sg-know CM-everybody ‘He knows everybody’ Suffix: attaches to the end of the host word Derivational suffix: -ness in happiness İnflectional suffix: past tense –ed İnfix: places itself inside a morpheme, usually a root or stem Derivational infix are used in the language Leti where the nominalizations are derived from the verb through the infix –niKakri ‘to cry’ -> kniakri ‘act of crying’ pali ‘to float’ -> pniali ‘act of floating’ İnflectional infix can be found in Maranao where –i- is used to mark the past tense Tabasan ‘slash’ -> Tiabasan ‘slashed’ Circumfix: at least two types of affixation have to occur at the beginning and at the end of the host at the same time. İnflectional circumfix can be found in German: past participle which combines of the prefix ge- and the suffix –t Example: lieben ‘to love’ -> geliebt ‘had loved’ We can find derivational circumfix in Indonesian ke- … -an which derives abstract nouns Example: kebebasan ‘freedom’ from the adjective bebas ‘free’ Parafix: has two affixes which do not have to occur at specific places like in circumfix For example in the language Leti: the nominalizations are derived with i- + -inatu ‘to send’ -> iniatu ‘act of sending’ Difference between clitics and affixes is that while both are phonologically dependent on a host, a clitic is syntactically independent from its host while an affix is not This means that affixes can only attach to the kind of hosts that match their category. For example the verbal affix –ed can only attach to verbs. And plural affixes can only attach to nouns and so on. Clitics not restricted to the kind of category they match to. Proclitic: attaches to the beginning of the host French pronouns may attach protoclitically: J’attends -> 1sg=wait.PRES -> I’m waiting Enclitic (also called postclitic) attaches at the end of the host Italian pronouns may attach enclitically: E venuto per parl-ar=mi 3SG.is come.PFCT to talk-INF=1SG.O ‘He has come to talk to me’ Mesoclitic: attaches itself between the host and the inflectional affixes. Very rare seen but can be found in European Portuguese: Pedirlheia Pedir=lhe=ia Ask.INF=3SG.M=1SG.COND Endoclitic: extremely rare because it takes place inside the root or stem Udi and Pashto are the only two languages which have endoclitics Languages have been classified along a linear scale with isolating languages on one end, fusional languages on the other and agglutinating languages in the middle; adding a fourth category is introflexive. İsolating>agglutinative> fusional> introflexive Mandarin Turkish Latin Arabic Chinese is an isolating language. Turkish is an agglutinating language. Linear scale merges three different parameters, fusion, exponence and flexion. The fourth parameter is synthesis which has to do with how much grammatical information a word may carry. Fusion states the degree to which morphological markers attach to a host stem. There are three types of fusion: İsolating is an independent word, a marker stands alone as a free morpheme. Markers that are bound are concatenative. They have to attach to a host. Markers that involve modifying the host in some way are nonlinear. Languages may employ any and all of the types of fusion. English has isolating markers ( the modal ‘must’ in He must be home by now) concatenative markers ( plural -s in tree (SG) versus trees (PL)) non-linear markers (the ablaut in sing – sang – sung). Most languages have at least some markers that stand in phonological isolation and thus function as individual words. An example in English would be the modal must, as in He must be in his office. There are languages where all or almost all grammatical information is conveyed though isolating markers. Koyra Chiini: ay woo kaa wor o guna 1SG.S DEM. REL. 2PL.S IPF see ‘I here whom you (PL) see.’ All grammatical information is expressed as individual words, even the tense of the verb (the imperfect marker o). Concatenative means ‘chaining together’. Apart from the fact that they are bound, they chain together in linear strings, which means that they are segmentable. A language with concatenative constructions is Chichewa, where the various markers attach linearly to the stems. Chichewa mlenje mmôdzi anabwérá m-lenje m-môdzi a-na-bwérá ndí míkôndo ndí mí-kôndo I-hunter ı.sm-one ı.sm-past-come with ıv-spears ‘One hunter came with spears.’ The grammatical markers for noun class (ı m/a and ıv mi) and past tense (na) are bound and are relatively straightforward to segment into morphemes. Non-linear markers involve some kind of modification to the host stem and are not straightforward to segment into chains of morphemes. Languages modify their stems non- linearly. A root consists only of a set of consonants and grammatical information is conveyed through insertion of a pattern of vowels, commonly termed the “root-and-pattern” but it is also termed ablaut. Neither the root nor the vowel pattern can function on its own. Modern Hebrew is a language with such a pattern; g-d-r ‘enclose’ past: a-a (CaCaC): gadar ‘enclosed’ present: o-e future: yi-Ø-o (CoCeC): goder (yiCCoC): yigdor ‘will enclose’ imperative: Ø-o (CCoC): infinitive: li-Ø-o (liCCoC): enclose’ gdor ligdor ‘encloses’ ‘enclose!’ ‘to Another example of ablaut (also called gradation or vowel gradation) is found in the strong verbs in Germanic languages, where inflection is marked through changes in the root vowel quality, as in English sing – sang – sung (present – past – past participle). Suprasegmentals (or prosodic formatives), involving tone, stress and length, are another type of non-linear morphological processes. Tone is a well-known morphological strategy, An example of a language with grammatical tone is Lango. a- àpônnê 1SG.hide.PFV.MID 1SG.hide.PROG.MID ‘I hide myself.’ myself.’ b- ápònnê ‘I am hiding Replacement or substitution is a regular marker and replaces a part of the stem. Another type of replacement is suppletion, where a root or stem is replaced by a root or stem of a different etymological origin. A rare type of non-linear process is subtraction, where the grammatical information lies in taking out an element of the stem. Reduplication falls consomewhere in between concatenation and non – linear process. It involves copying a set amount of phonological material from a base form (root or stem) and fusing it with that base to form a stem onto which other morphemes may then be added. It’s less linear than concatenative morphemes in that the form of the reduplicant (the repeated element) is dependent on the form of the base, since it is a part of the base that is being repeated. Reduplication can be either full or partial, and while the reduplicant usually attaches immediately to the root it has its shape from, there are also languages with socalled discontinuous reduplication, where other morphological material may appear between the reduplicant and the base. Also, reduplication can be simple or complex. In simple reduplication merely repeats a given amount of material from the base. Complex reduplication involves taking material from the base and partly altering it. Full reduplication involves copying the whole base. Most languages allow both full and partial reduplication. In Rubino’s database shows only 35 languages which are allow full reduplication. Here is an example of a language with full simple reduplication is Erromangan, where reduplication indicates intensification. Erromangan (Austronesian (Oceanic): Vanuatu /unmeh/ “early” >> /unmehunmeh/ “very early” /ilar/ “shine” >> /ilarilar/ “shine brightly” (Crowley 1998:34) An example of a full complex reduplication can be found in Persian, where the reduplicated form changes the initial consonant to either /m/ or /p/ of copied element. The reduplicated form takes a meaning of what we might call “scattered generality”, most closely equivalent to English ‘and so forth’. Persian ( Indo – European (Iranian): Iran) bâlâ “ above” >> bâlâmala “somewhere above” mive “fruit” >> mivepive “fruit and so on” (Ghaniabadi et al. 2006:3) Partial reduplication involves copying only a set part of the base and may involve a number of different forms. It can be a set of phonemes (C,CV,CVCV, and so on) , a set of syllabes or a set of morae (the minimal unit of metrical weight) that is copied. (Rubino, 2011) In Thao the instrumental is expressed by Careduplication, which means that the first consonant of the base is copied and -a- is added (also called duplifix, Haspelmath 2002:24): Thao (Austronesian (Paiwanic): Taiwan) cput “to filter” >> cacput “sieve” >> c - a - cput An example of a partial complex reduplication can be found in Nakanai; velo “bubbling” >> velelo “bubbling forth” ve - le - lo Automatic reduplication is when an affix obligatorily triggers reduplication but the reduplication itself does not add any meaning to the construction. An example of an automatic reduplication can be foun also in Tagalog; Tagalog (Austronesian (Meso – Philippine): Philippines: wilih “interested” >> kawilihwilih “interested” ka – wilih – wilih (French 1998:50) As it is mentioned above, the reduplicant might be seperated from the base by some particle. An example of such a discontinuous reduplication can be found in the Manila Bay Creoles, which is a cover term for Ternateno, Caviteno, and Ermiteno, where the linker - ng - sits between the reduplicant and the base. Manila Bay Creoles (Creole (Spanish – lexified): Philippines) Bunita “beautiful” >> bunitangbunita “very beautiful” bunita – ng – bunita (Grant 2003:205) All these examples implies that pidgings and creoles do not seem to behave differently from non – creole languages in terms of employing the morphological process of reduplication. In Turkish, the process of emphatic reduplication, the purpose of which is to accentuate the quality of an adjective, involves the copying of the initial (C)V of the base and then prefixing it, along with an additional affixal consonant from the set /p, s, m, r/, to the base, as seen in (1). In some cases, the emphatic (C)VC prefix is also followed by –A, –Il, or –Am, as seen in (2). Cases such as those in (2) are considered idiosyncratic and are not the result of a productive phonological process (Göksel and Kerslake 2005). (1) güzel ‘pretty’ uzun ‘long’ katı ‘hard’ siyah ‘black’ temiz ‘clean’ güpgüzel ‘very pretty’ upuzun ‘very long’ kaskatı ‘hard as a rock’ simsiyah ‘pitch black’ tertemiz ‘clean as a pin’ (2) gündüz ‘daytime/by day’ broad daylight’ yalnız ‘alone’ çıplak ‘naked’ parka ‘piece’ to pieces’ güpegündüz ‘in yapayalnız ‘all alone’ çırılçıplak ‘stark naked’ paramparça ‘torn to shreds/smashed Doubling occurs in two ways: simple doubling and doubling in lexical formations. In simple doubling, the word is repeated. Depending on the syntactic category of the targeted lexeme, it can produces adverbials, adjectivals and measue terms (Göksel & Kerslake 2005). tek tek zaman zaman one DUP time DUP “one by one” “time to time” Some additional morphemes, such as plural suffix and the question particle, are attached to the sister conctituents or one of the constituents undergoes phonetic changes for doubling in lexical formations güzel-ler güzel-i bir kız beautiful-PLU beautiful-POSS a girl ‘a very beautiful girl güzel mi güzel bir kız beautiful QP beautiful a girl ‘a very beautiful girl’ ufak tefek bir kutu little fi(little) a box ‘a tiny box’ Examples: With Synoynms; güçlü kuvvetli, ses seda, sağlık sıhhat, evirmek çevirmek etc. With nearly the same meanings; eş dost, doğru dürüst, ağrı sızı, sağ salim etc. With antonyms; iyi kötü, aşağı, yukarı, irili ufaklı, acı tatlı etc. With meaningless words; abuk subuk, abur cubur, eciş bücüş, apar topar etc. With Onomatopoeia words; tıkır tıkır, şırıl şırıl, horul horul, vızır vızır etc. Languages also differ as to how many grammatical categories may be expressed by one and the same morpheme. Seperative morphemes(or monoexponential) morphemes encode only one single category, cumulative (polyexponential, also called portmanteau) morphemes encode several things at the same time. This parameter may interact with fusion, so that we get six logical logical combinations: isolating, concatenative, and non-linear seperative markers plus isolating, concatenative, and non-linear cumultative markers. Here is a list for languages with examples of each of the six logical types of processes. Kasong: isolating seperative Meithei: concatenative seperative Dinka: non-linear seperative Wari: isolating cumulative Spanish: concatenative cumulative Hebrew: non-linear cumulative For Kasong language, each of the markers is a free morpheme. They are isolating , and each of them conveys only one piece of information, the markers are seperative: Kasong nak kamlaŋ loŋ ce:w prǐ 3.SG PROG. FUT. go forest ‘s/he will be going to the forest.’ Meithei(Sino-Tibean (Kuki-Chin): India) offers an example of concatenative seperative markers. The markers fuse concatenatively with a host stem; they are linearly segmentable and each of the segments in that each conveys only one piece of information. Meithei ǝynǝ thǝŋ ǝy-nǝ thǝn ǝmǝnǝ hǝydu kháy ǝ-mǝ-nǝ hǝy-tu kháy-i 1.SG-CNTR knife ATT-one-INST ‘ I cut the fruit with a knife.’ fruit-DDET cut-NHYP (Chelliah 1997:128) Dinka language has non-linear seperative process, where the absolute and locative cases are distinguished only through phonological length. The marker conveys only the information of case, and is as such seperative, but it is not possible to segment from the host word, and is therefore non-linear. Dinka tôoc tôooc ‘swampy.area.ABSOLUTIVE ---‘swampy.area.LOCATIVE’ (ANDERSEN 2002: 13) Wari is an example a language with isolating markers, that is the morpheme form seperate words. However, they are cumulative in that they contain more than one piece of grammatical information, and this information is not possible to segment into smaller units. Wari ma’ co that.PROX.HEARER ‘ Who is speaking? ’ tomi INFL.M/FRP/P na speak 3SG.RP/P.VIC (Everett 1998: 692) Spanish also makes use of cumulative markers that fuse concatenatively onto the stem, which gives us a concatenative cumulative morphological process. Spanish habl-ó speak-3sg.past.ind.pfv ‘He spoke.’ (source: personal knowledge) In Hebrew has a non-linear cumulative process. It means a similar amount of information is expressed through only one single process, but the process involves modifying the root itself and is thus non-linear. Modern Hebrew g-d-r ‘enclose’ future active indicative: yigdor ‘will enclose’ future passive indicative: yigader ‘will be enclosed’ (Glinert 1989: 471) the way the stem is modified conveys more than one piece of information: the tense, the voice, and the mood. However, this grammatical information is not segmentable: if you want to change any of the grammatical information, for instance from active voice to passive you have to modify the root to an entirely different stem. FLEXIVITY Languages also differ in how much allomorphy they have, termed flexitivity in Bickel & Nichols (2007). The Indo-European declension and conjugation classes are examples of flexitivity. That is where a set of infectional affixes are chosen depending on which class the noun or verb belongs to. On the other hand, a given grammatical marker is always the same. It does not vary according to classes of verbs or nouns, it is nonflexive. If a language has five different ways of marking the (nominative) plural, with -e, -er, (e)n -s, or –Ø, depending on which class the noun belongs to, we have an instance of flexitivity. It exhibited in German. If the plural is always marked the same way, as is the case with Pichi dέn (Yakpo 2009), we have an instance of nonflexitivity. This is a third and seperate parameter from fusion and exponence and may interact with them in various ways. We have four logical combinations with the languages exemplifying types included. Cumulative English Separative Flexive German Nonflexive Hawai‘i Creole Warlpiri Pichi German is an example of flexive cumulative morphemes. Because , the choice of which allomorph to take depends on which declension class the noun belongs to flexitivity and the markers express both number and case cumulative. An example of a nonflexive cumulative marker is the Hawai’i Creole English. For example; wεn which expresses both tense (past) and aspect (perfective) at the same time. It is cumulative. The plural marker in Pichi is an example of an nonflexive seperative marker because it is invariant as the plural marker nonflexive and it means only plural and nothing else (seperative). An example of a flexive separative marker can be found in Warlpiri where the ergative case is marked either with -ngku or with –rlu. It is flexive in that there are two alternative ways of marking ergative case, and it is separative in that it means only one thing (ergative). Likewise, flexitivity interacts with fusion. %e German plural marking mentioned above is both flexive and concatenative; this is, in fact, the most common combination. Flexive nonlinear strategies are common in Semitic languages; we have seen that Hebrew expresses tense, mood and voice through a set of vocalisms. Flexive isolating markers are very rare but can be found in Sierra Otomí, where person and tense is marked by a free morpheme which looks different depending on what conjugation class the verb belongs to: Sierra Otomí 1sg.pres verb conjugationclass dí petsi ‘I keep (it)’ I dín tófo ‘I say (it)’ II dídí hóqui ‘I -x (it)’ III dídím pepfi ‘I work’ IV The Pichi plural marking mentioned above is an example of a nonflexive isolating marker. This is is pretty typical: “[n]onflexive formatives are often isolating; and the most common type of isolating formative is nonflexive. (Bickel &Nichols 2007:187) Turkish is an example of a language where the plural marker -lar is nonflexive concatenative – also a very common strategy – as it attaches to a host but is segmentable, and is invariable, i.e. is used for all nouns (Kornfilt 2003: 265) An example of a nonflexive non-linear marker is the perfective marker in Kisi. It invariably expressed through a LH tone (Childs 1995: 173). Here is a table summarizing for the six logical combinations with the languages exemplifying each type included. Flexive Nonflexive Isolating Sierra Otomí Pichi Concatenative German Turkish Non-linear Hebrew Kisi What we have seen is that languages employ different strategies. And that these strategies themselves fall along three separate parameters that all interact with each other. Another parameter is that of Synthesis, which can thought of as a scale indicating how much accumulated information a word can hold, as opposed to the parameters given above, which, again very simplified, basically denote what kinds of morphemes languages tend to have and how they combine. But bear in mind that I am simplifying matters considerably by merging the concepts of phonological word and grammatical word. There are three basic types of synthesis, which can be pictured as standing in a linear arrangement to each other. ANALYTIC > SYNTHETIC > POLYSYNTHETIC ANALYTIC words do not take any affixation to their lexical roots or stems. An analytic way of marking tense, for example, is found in the English future, as in He will walk home. SYNTHETIC words allow affixation. An example of synthetic tense in English is the past, expressed through the –ed affixation, as in He walked home. English typically does not take a high amount of affixation. For instance, while the grammatical coding of comparative for adjectives tends to be done synthetically if the stem is rather short, an analytic construction is favourred if the stem is rather long. The Chichewa Example also shows instances of synthetic words, where several pieces of grammatical information are attached to the lexical root or stem. But a synthetic word can also end up being very long. A spectacular case of synthesis can be found in Turkish. TURKISH ( Altaic ( Turkic ): Turkey ) tanıştırılamadıklarındandır tan-ış-tır-ıl-a-ma-dık-lar-ın-dan-dır “it is because they cannot be introduced to each other.” The crucial difference between synthetic and polysynthetic words is that the latter involve more than ne lexeme. While the Turkish example is very long and involves a great deal of segments, there is only one lexeme, tan ‘know’. Polysynthetic words, however, may contain more than one lexeme. Alutor is an example of a language with polysythetic words. ALUTOR (Chulotko- Kamchatkan ( Northern Chukotko- Kamchatkan): Russia) gəmmə gəmmə tk-ən takkannalgənkuwwatavətkən t-akka-n-nalgə-n-kuww-at-avə- ‘I am making a son dry a skin/skins.’ The Turkish word tanıştırılamadıklarındandır in as long as the Alutor word takkannalgənkuwwatavətkən but the Turkish word is synthetic while the Alutor word is polysynthetic. This is because the Alutor word contains three different lexemes, akka ‘son’, nalgə ‘skin’ and kuww ‘dry’. Although polysynthetic words tend to be long, they do not necessarily have to be as following. Mamaindê ( Nambikuaran (Nambikuaran):Brazil) Jukhoʔth ɪ̈ntu Ju-khoʔ-th ɪ̈n-tu ‘village hanging on the edge’ The mamainde word is shorter than the Turkish word but is still a case of polysynthesis, since it contains two lexemes ju ‘edge and khoʔ ‘hang’. Sign languages, just like spoken languages, have minimal meaningful units, i.e. morphemes, and instances where units may alternate, i.e. allomorphy. Morphemes may either free or bound. In other words signed languages are as linguistically complex as spoken languages. However, due to the fact that sign languages make use of an entirely different mode of communication, visual instead of audio, morphology in sign language tends to be less concatenative than in spoken languages. Compounding, which is also sequential in nature, is very common in sign languages. An example of a compound is the ASL sign for faint which consists of the signs MIND+DROP. An example of a derivation is the ISL negative suffix, which,similar to the English –less, derives adjectives, for instance shameless in the construction SHAME + neg. This negative suffix has two allomorphs, signed either with one hand or two, depending on the host it attaches to. Examples of prefixes are the ISL.’sense’ prefixes: to denote that something has to do with perception ( seeing/hearing/smelling) a reduced and bound EYE-SHARP ‘to discern by seeing’. Examples of cliticized forms occur in Turkish Sign Language ‘TİD’ and DGS. In TİD the negator NOT may attach itself to the preceding sign and form part of a phonological unit with that host: it (en)cliticizes. Non-linear morphological processes are very common in sign languages. For example, verbs are very often modified non-linearly for agreement with the subject and object or for aspect. What is non-linear about much of sign language and morphology is that the base of the sign, the stem, is modified as to its rhythm, path or direction to indicate the relevant grammatical information. It seems as if sign languages universally make use of what has been termed classifiers. They modify verbs and typically decode the shape of objects, the handling of an object and the movement and location of referents. With classifiers, “ the handshape of one or both hands represents a particular type of referent, while the location, arrangement and movement of the hand expresses something about referrent”. These classifiers are organized paradigmatically. An example of a complex sign using clasifiers would be expressing the sentence The car hits a tree ( and gets wrekced) in ASL. Here non-dominant hand is configured for the clasifier “tree” while the dominant hand is configured for “vehicle”, signs “move” and adds the configurations for “wrecked” at the end of the motion. There are two major types of classifiers, entity classifiers and handling classifiers. Sign languages vary in the amount of classifiers they have. For example, NGT has 17 classifier hand-shapes while Indo-Pakistani Sign Language only has two, “legs” and “person”. Many sign languages make use of reduplication to express the general concept of “more of the sasme”, similarly as in spoken languages. Sign reduplication is done by having the sign make an arch and thereby repeating the location-movement-location pattern in one fluid motion. A reduplicated verb will typically indicate a longer duration of the event (durative), or that is occurs habitually(habitual), or that it occurs repeatedly(iterative). A reduplicated noun typically indicated plurality. Both spoken and signed languages make use of morphemes. These can be either bound or free. The core of a lexeme is a root or a stem, the difference between the two being that the root is not further analysable into any smaller parts, while a stem may consist of a root plus something else. Affixes are bound morphemes that do not carry any lexemic information and that are syntactically dependent on what kind of host they may attach to. Clitics are also bound morphemes, but while they are phonologically dependent on a host, they are not syntactically dependent on what they may attach to. Both affixes and clitics can attach at different places on their hosts. Fusion indicates how tightly morphemes attach to each other. Reduplication is a kind of fusion. Exponence indicates how much information each morpheme conveys. Flexion denotes how much allomorphy a language has. A seperate, fourth, parameter is that of synthesis, which denotes how much information, both grammatical and lexemic, a word may carry. Sign languages are as morphologically complex as spoken languages, but due to their difference in modality- spoken languages being dependent on the sequential nature of sound while signed languages have at their disposal the simultaneity of the visual medium- spoken languages are predominantly linear in their morphological processes while signed languages are predominantly non-linear.