Click here to the file.

advertisement

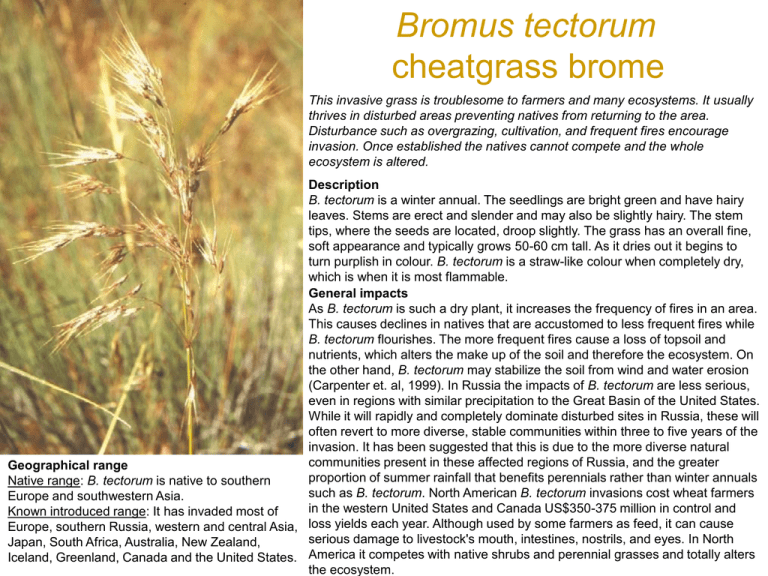

Bromus tectorum cheatgrass brome This invasive grass is troublesome to farmers and many ecosystems. It usually thrives in disturbed areas preventing natives from returning to the area. Disturbance such as overgrazing, cultivation, and frequent fires encourage invasion. Once established the natives cannot compete and the whole ecosystem is altered. Description B. tectorum is a winter annual. The seedlings are bright green and have hairy leaves. Stems are erect and slender and may also be slightly hairy. The stem tips, where the seeds are located, droop slightly. The grass has an overall fine, soft appearance and typically grows 50-60 cm tall. As it dries out it begins to turn purplish in colour. B. tectorum is a straw-like colour when completely dry, which is when it is most flammable. General impacts As B. tectorum is such a dry plant, it increases the frequency of fires in an area. This causes declines in natives that are accustomed to less frequent fires while B. tectorum flourishes. The more frequent fires cause a loss of topsoil and nutrients, which alters the make up of the soil and therefore the ecosystem. On the other hand, B. tectorum may stabilize the soil from wind and water erosion (Carpenter et. al, 1999). In Russia the impacts of B. tectorum are less serious, even in regions with similar precipitation to the Great Basin of the United States. While it will rapidly and completely dominate disturbed sites in Russia, these will often revert to more diverse, stable communities within three to five years of the invasion. It has been suggested that this is due to the more diverse natural communities present in these affected regions of Russia, and the greater Geographical range proportion of summer rainfall that benefits perennials rather than winter annuals Native range: B. tectorum is native to southern such as B. tectorum. North American B. tectorum invasions cost wheat farmers Europe and southwestern Asia. in the western United States and Canada US$350-375 million in control and Known introduced range: It has invaded most of Europe, southern Russia, western and central Asia, loss yields each year. Although used by some farmers as feed, it can cause serious damage to livestock's mouth, intestines, nostrils, and eyes. In North Japan, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Iceland, Greenland, Canada and the United States. America it competes with native shrubs and perennial grasses and totally alters the ecosystem. Arundo donax bamboo reed Giant reed is a perennial grass which has been widely introduced into primarily riparian zones and wetlands in subtropical and temperate areas of the world. Once established, it forms dense, homogenous stands at the expense of native plant species, altering the habitat of the local wildlife. It is also both a fire and flood hazard. Description Large statured clump-forming grass, 3-10 meters tall with many stems from a shallow, horizontal rhizome. Stem or culm hollow with bamboo-like nodes, 1-4 cm diam., typically unbranched the first year and forming branchlets from nodes in subsequent years or when damaged. Leaves clasping and long (to ca. 70 cm), alternately arranged in a single plane, the ligule fringed with longish hairs. May form plume-like terminal inflorescence, but often non-flowering in higher latitudes Occurs in: agricultural areas, coastland, desert, disturbed areas, natural forests, planted forests, range/grasslands, riparian zones, scrub/shrublands, urban areas General impacts Displaces native riparian vegetation and provides poor habitat for terrestrial insects and wildlife. Traps sediments and narrows flood channel, leading to erosion and overbank flooding. Promotes wildfire and debris blocks streamflow and damages bridges.May reduce water availablility through high evapotranspiration. Geographical range Native range: Considered native to Indian sub-continent, now occurs worldwide in tropical to warm-temperate regions, inluding tropical islands. It is present in the Federated States of Micronesia (Pohnpei), Guam (rare per Stone, 1970), Republic of Palau (Koror), Fiji, Hawai'i, Nauru, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island and Samoa as well as Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. An ornamental variety, Arundo donax var. versicolor (Mill.) Stokes is widely cultivated. It has white-striped leaves and is reported to be under cultivation in Fiji and Palau. It has been widely planted throughout the warmer areas of the U.S. as an ornamental. It is especially popular in the Southwest where it is used along ditches for erosion control (Perdue 1958). Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum butternut canker Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum, is the cause of a lethal stem disease, butternut canker. It causes multiple cankers on the main stem, branches, and twigs of butternut, Juglans cinerea. Cankers commonly occur at the base of trees and on exposed buttress roots and can survive and sporulate on dead trees for at least 13 years or more. The fungus may be threatening the viability of butternut as a species. Host Range: Recent research studies using artificial inoculations have revealed that the pathogen can attack other highly valuable species of the family Juglandaceae; such as black walnut, Japanese walnut, Persian walnut, and heartnut as well as various hybrids of these species. This wide host range of the pathogen has attracted international concern. Both seedlings (Feberspiel and Nair, 1982) and 10 to 20 year old field planted trees of all species mentioned proved to be susceptible (Orchard et al. 1982, Gabka 1986). In addition, black walnuts growing in a mixed stand of severely diseased butternuts have been found infected naturally. However, heartnut, Japanese walnut and hybrids between then and butternut exhibited greater resistance to the pathogen, developing smaller cankers, than the highly valuable black walnut and Persian walnut. (Nair, V.M.G. 1999) Description Diagnostic Systems include elliptical to fusiform cankers formed on the main stem and branches. Young cankers originate at leaf scars lenticells bark wounds and buds, often with an inky black center and whitish margin. Peeling the bark away reveals the brown to black elliptical areas of killed cambium. Older branch and stem cankers are perennial, found in bark fissures or covered by shredded bark, and boardered by successive callus layers. Cankers commonly occur at the base of trees and on exposed buttress roots. Branch cankers usually occur first in the lower crown and stem cankers develop later from spores washing down from branch cankers. The fungus can survive and sporulate on dead trees for at least 13 years (Nair. V.M.G, 1999). Authors of a study report that cankers develop first on branches in the lower crown. This is followed by branch mortality and sporulation by the fungus. Trunk cankers develop1-3 yr after initial branch mortality. The authors report that trees with tops killed by coalescing basal cankers did not resprout at the root collar (Tisserat and Kuntz, 1984; Nair, V.M.G, 1999). Occurs in: host, natural forests, planted forests Ophiostoma ulmi dutch elm disease Occurs in: natural forests, planted forests, urban areas Geographical range Native range: The origin of the fungus O. ulmi, the causal agent of Dutch elm disease, remains unknown but it is probably native to Asia. Known introduced range: O. ulmi was introduced in Europe around 1910 and from here was introduced into America, where it arrived around 1930. The disease is prevalent in Canada and has been controlled in New Zealand. Dutch Elm disease is a wilt disease caused by a pathogenic fungus disseminated by specialized bark beetles (Brasier, 2000). There have been two destructive pandemics of the disease in Europe and North America during the last century, caused by the successive introduction of two fungal pathogens: Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi , the latter much more aggressive. The vector is represented by bark beetles, various different species of scolyts living on elm. These beetles breed under the bark of dying elm trees. The young adults fly from the DED infected pupal chambers to feed on twig crotchtes of healthy elm trees. As a consequence spores of the fungus carried on the bodies of these beetles are deposited in healthy plant tissue. O. ulmis.l. can also spread via root grafts. Description According to Partridge (1997), O. ulmi s.l. is a rather complex fungus. It has four spore types: conidia produced on mycelium, conidia borne on a mycelial stalk (synnema), yeast like spores that are variable in size, and ascospores, which are produced in a black fruiting body (perithecium) which ooze through the long neck of the perithecium, and accumulate at the tip in sticky mass. Management information Preventative measures: According to Stack et al. (1996), Dutch elm disease cannot be eliminated once it begins. A year-round community sanitation program is the key to slowing the spread of the disease. The most available control is removing infected trees and promptly destroying the wood. If infected wood is to be used as firewood, it should first be debarked. Trenching to disrupt root grafts is also recommended to protect healthy elm trees near diseased ones. In urban situations, insecticide spraying of high value trees has been effective in keeping bark beetles from attacking susceptible trees. In ornamental plantings, suggested control measures include planting trees further apart to prevent root grafts or choosing mixed tree species. The use of resistant selections for new plantations is strongly recommended. Occurs in: host, natural forests, planted forests Geographical range Native range: Asia (EPPO, 2004). Known introduced range: Europe and North America (EPPO, 2004). C. parasitica is a fungus that attacks primarily Castanea spp. but also has been known to cause damage to various Quercus spp. along with other species of hardwood trees. American chestnut, C. dentata, was a dominant overstorey species in United States forests, but now they have been completely replaced within the ecosystem. C. dentata still exists in the forests but only within the understorey as sprout shoots from the root system of chestnuts killed by the blight years ago. A virus that attacks this fungus appears to be the best hope for the future of Castanea spp., and current research is focused primarily on this virus and variants of it for biological control. Chestnut blight only infects the above-ground parts of trees, causing cankers that enlarge, girdle and kill branches and trunks. General impacts C. parasitica has had a negative cascading effect upon native forest composition and diversity throughout most of the United States since its introduction. Davelos and Jarosz (2004) state that, "American chestnut, C. dentata, was a dominant overstorey species in hardwood forests of the eastern United States of America prior to the introduction of blight (Day and Monk, 1974; Karban, 1978; Russell, 1987). In Southern Appalachian forests, the loss of mature chestnuts may have substantially reduced the forest's carrying capacity for certain wildlife species (Diamond et al., 2000). After the spread of C. parasitica, oak (Quercus spp.), red maple (Acer rubrum) and hickory (Carya spp.) became the dominant overstorey tree species (Keever, 1953; Stephenson, et al., 1991). Today, chestnuts continue to be an important understorey species because of sprouts produced by extant tree root systems (Keever, 1953; Russell, 1987; Stephenson et al., 1991). However, infected sprout clusters exhibit reductions in survival and size, particularly when in competition with other hardwoods (Griffin et al., 1991; Parker et al., 1993). Vandermast et al. (2002) state that, "Allelopathic qualities of chestnut leaves could have affected large areas of eastern forests. Chestnut foliage was dense, the leaf litter abundant and the leaves slow to decay ( Zon, 1904). Other studies indicate rain throughfall, dripping off live foliage, can contain concentrations of phytotoxic chemicals sufficient to inhibit germination of co-occurring species ( Al; Lodhi and Nilsen). With the abundance of competitive tree and shrub species in the southern Appalachians, it is possible allelopathy had an influence on maintaining chestnut's dominance in the region." Aulacaspis yasumatsui Asian cycad scale The armoured scale insect, Aulacaspis yasumatsui, commonly known as the cycad aulacaspis scale (CAS) or the Asian cycad scale is highly damaging to cycads, which include horticulturally important and endangered plant species. The cycad scale is an unusually difficult scale insect to control, forming dense populations and spreading rapidly, with few natural enemies in most localities where it has been introduced. The scale has the potential to spread to new areas via plant movement in the horticulture trade. Description All adult female armoured scale insects have a waxy outer covering for the protection of themselves and their eggs (the scale) (Weissling et al. 1999). The scale of mature females of A. yasumatsui are: "white, 1.2-1.6 mm long and highly variable in form. They tend to have a pyriform shape with the exuviae at one end, but are often irregularly circular, conforming with leaf veins, adjacent scales and other objects. The ventral scale is extremely thin to incomplete. The scale of the juvenile male is similar to those of other species of Diaspididae, being 0.5-0.6mm long, white and tricarinate, with exuviae at the cephalic end. Scales of males are nearly always more numerous than those of females" (Howard et al. 1999). Adult males are orange-brown, and are similar in appearance to tiny flying midges, with one pair of wings and well-developed legs and antennae (Heu et al. 2003). Adult females are also orange in colour (Weissling et al. 1999). Habitat description CAS is found on plants from the gymnosperm order Cycadales, which consists of three families - Cycadaceae (Cycas a genus that contains its preferred host species), Stangeriaceae (Stangeria) and Zamiaceae (8 genera). Geographical range Native range: Southeast Asia (Howard et al. 1999; Muniappan, 2005). According to Dr. Chandrashekara and Dr. A. Viraktamath of the Department of Entomology at the University of Agricultural Sciences in Bangalore, India, CAS has so far not been recorded in India. Please see Update on CAS native range. Known introduced range: USA (Florida, Hawai‘i, Georgia, Texas, Alabama, California, Louisiana, South Carolina), Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico and Vieques Islands, US Virgin Islands, Singapore, Hong Kong, Guam. Intercepted at the border in France. Intercepted at the border in New Zealand and eradicated. Anoplolepis gracilipes crazy ant This species has been nominated as among 100 of the "World's Worst" invaders Workers of Anoplolepis gracilipes respond rapidly to disturbance of the litter layer Occurs in: agricultural areas, coastland, disturbed areas, natural forests, planted forests, range/grasslands, riparian zones, scrub/shrublands, urban areas, water courses Description A. gracilipes, or the yellow crazy ant, is one of the largest invasive ants, (invasive ants are typically small to medium-sized and range from 1-2mm to more than 5mm). This species, also known as the long-legged ant, is notable for its remarkably long legs and antennae. A. gracilipes workers are monomorphic, displaying no physical differentiation. It has a yellow-brownish body colour, and is weakly sclerotized. Workers have a long slender gracile body, with the gaster is usually darker than the head and thorax. It may subdue or kill invertebrate prey or small vertebrates by spraying formic acid. Anoplolepis gracilipes commonly known as the yellow crazy ant is associated with human-modified environments, such agricultural areas or urban zones. On some tropical islands, including the Seychelles and Christmas Island, it has reached high densities, devastating native invertebrate and vertebrate populations, especially previously-threatened birds. In at least one case its removal of a keystone species has resulted in a change in forest composition and a decrease in nutrient cycling. It affects native fauna by competing for food resources, altering the habitat or predation. By lowering biodiversity, it indirectly threatens tourism sectors. Its relationship with various honeydew-producing insects exuberates scale insect populations, affecting native flora and causing significant damage to plants and economic losses in agricultural systems. Geographical range Native range: The long-legged ant remains poorly studied and even its native range is not certain. It may have originated from Africa or Asia (Holway et al. 2002). The centre of diversity for the genus is Africa and A. gracilipes is the only species distributed beyond that continent. Vulpes vulpes Red Fox Native to Europe, Asia, North Africa, and boreal regions of North America, European red foxes have been introduced into Australia and temperate regions of North America. They are now the most widely distributed carnivore in the world and have negative impacts on many native species, including smaller canids and ground nesting birds in North America, and many small and medium-sized rodent and marsupial species in Australia. Occurs in: agricultural areas, disturbed areas, natural forests, planted forests, range/grasslands, riparian zones, tundra, urban areas Description Three color morphs are generally recognized: red, silver or black, and cross. A pale-yellowish color morph is common on the Arabian peninsula, and within native subspecies in North America. In general, throat and abdomen are white, lower legs and ears are black, and a bushy tail is tipped in white. This species exhibits a wide geographic and subspecies variation in size, as body length can range from 45 to 90 cm, tail length from 30 to 55 cm, and body mass from 3 to 14 kg. General impacts In Austrialia, red foxes have eliminated remnant populations of some native rodent and marsupial species on the mainland, and evidence suggests they are the primary cause in the decline and extinction of many other small and medium-sized rodent and marsupial species. In North America, introduced red foxes have negative impacts on many ground-nesting birds, such as ducks and grouse. In California, introduced red foxes have to be controlled on an annual basis to protect the nesting grounds of several endangered species of birds. Introduced red foxes also negatively impact smaller native canids, such as the endangered San Joaquin kit foxes, and subspecies of native red foxes. Evidence suggests introduced red foxes might have already completely replaced several native subspecies of red foxes across Canada. Introduced red foxes are also a threat to livestock, as they prey on poultry, lambs, and kids. Finally, their high densities pose a health threat to humans and pets through transmission of diseases, especially rabies, but also distemper, parvo virus, and mange. Geographical range Native range: Europe, North Africa, most of Asia (excluding extreme Southeast Asia and southern India), and boreal regions of North America. Red foxes are now the most widely distributed carnivore in the world.