Troilus and Cressida and genre

advertisement

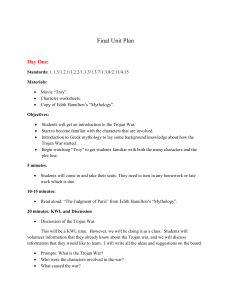

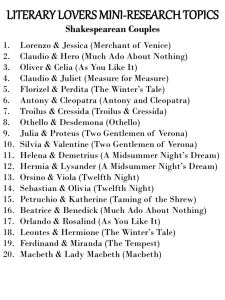

EN301: Shakespeare and Selected Dramatists of his Time Tragical-comical-historical? See internetshakespeare.uvic.ca and www.bl.uk/treasures/shakespeare/homepage.html for page scans of early printed Shakespearean texts. The 1623 Folio contents page Troilus and Cressida is not listed on the Folio contents page, suggesting it may have been a late addition. In the Folio itself, the text is positioned squarely between the last of the histories and the first of the tragedies… The 1623 Folio text The two 1609 Quarto title pages The 1609 Epistle “Eternall reader, you have here a new play […] passing full of the palme comicall […] So much and such savored salt of witte is in his [the author’s] Commedies, that they seeme (for their height of pleasure) to be borne in that sea that brought forth Venus. Amongst all there is none more witty than this.” The play’s structure What does it resemble structurally? Comedy? Tragedy? History? None of these? It starts – and ends – seven years into the ten-year siege of Troy. PROLOGUE. … our play Leaps o’er the vaunt and firstlings of those broils, Beginning in the middle, starting thence away To what may be digested in a play. Like or find fault; do as your pleasures are; Now, good or bad, ’tis but the chance of war. (26-31) Troilus and Cressida the comedy? While the play is certainly not a festive comedy, it is full of satire and bawdy humour (not unlike city comedy in this respect?). Even a cursory glance at the shape of the dialogue in 1.1 reveals something about the scene’s structure… Note Pandarus’ constant attempts here to bring Troilus’ lofty discourse down to the level of the body… Cressida the comic? On her first appearance, Cressida’s jesting responses to Alexander and Pandarus’s descriptions of offstage men recall Portia’s in The Merchant of Venice and Lucetta’s in The Two Gentlemen of Verona: ALEXANDER. They say he is a very man per se, And stands alone. CRESSIDA. So do all men Unless they are drunk, sick, or have no legs. (1.2.15-17) PANDARUS. What, not [a comparison] between Troilus and Hector? Do you know a man if you see him? CRESSIDA. Ay, if I ever saw him before and knew him. (1.2.61-3) Cressida the comic? As Bridget Escolme argues, “Cressida herself can be inscribed with clown-like performance objectives, and accordingly, the Cressida figure /actor’s first function is to reassure the audience that the play has not abandoned the bathetic wit of the Prologue, despite Troilus’ recent appearance as perfect, and perfectly serious, chivalric lover. … Her technique is in the best tradition of fools, taking a figure of speech from its figurative context and deliberately misunderstanding it.” (2005: 42-3) Cressida the comic? Indeed, the lively banter between niece and uncle might remind us of Much Ado About Nothing: LEONATO. You will never run mad, niece. BEATRICE. No, not till a hot January. (1.1.88-9) PANDARUS. You are such another woman! One knows not at what ward you lie. CRESSIDA. Upon my back to defend my belly, upon my wit to defend my wiles, upon my secrecy to defend mine honesty, my mask to defend my beauty, and you to defend all these – and at all these wards I lie at a thousand watches. (1.2.254-60) Cressida the comic? This is very clever and witty, but it also hints at Cressida’s awareness of her vulnerability in a world that prizes her primarily for her sexual value: CRESSIDA. That she beloved knows nought that knows not this: Men prize the thing ungained more than it is. That she was never yet that ever knew Love got so sweet as when desire did sue. (1.2.284-7) Cressida the comic? Cressida worries throughout about giving too much of her inner life away, and upon losing her virginity almost immediately regrets her loss of agency: CRESSIDA. Prithee, tarry. You men will never tarry. O foolish Cressid! I might have still held off, And then you would have tarried. (4.2.18-20) Satire and the grotesque body You will remember from last week that for Mikhail Bakhtin, “The people’s laughter which characterized all the forms of grotesque realism from immemorial times was linked with the bodily lower stratum. Laughter degrades and materializes.” (1965: 19) We see the “grotesque body” most explicitly in the “deformed and scurrilous” Thersites: THERSITES. Agamemnon – how if he had boils, full, all over, generally? (2.1.2-3) Thersites is “a privileged man”, able to speak truth to power; his proving of Agamemnon, Achilles, himself and Patroclus to be fools is reminiscent of Feste in Twelfth Night (“Take the fool away”, 1.5.35-68). Satire and the grotesque body Every romantic liaison in the play is quickly reduced by those who speak about it to mere sex: Pandarus’ song to Helen and Paris is full of innuendo (“The shaft confounds / Not that it wounds, / But tickles still the sore”; 3.1.114-16) Troilus and Cressida’s first scene ends not with the lovers, but with a bawdy aside from Pandarus (“And Cupid grant all tongue-tied maidens here / Bed, chamber, pander to provide this gear”; 3.2.206-7) Their aubade scene is interrupted by Pandarus, who bursts in with the line “How now, how now, how go maidenheads?” (4.2.25) PANDARUS. Is this the generation of love: hot blood, hot thoughts, and hot deeds? Why, they are vipers. Is love a generation of vipers? (3.1.128-30) The limits of comedy? Can we call a play a comedy or a satire when it asks us to share so much of its characters’ emotional pain? Remember Bergson’s dictum: laughter is usually accompanied by an “absence of feeling” (1900: 63). Indeed, does the play ask us to judge Cressida, or to sympathise with her? Or both? Troilus and Cressida the history play? Shakespeare’s audience knew this story: indeed, Shakespeare alludes to it in numerous plays. The plot concerning the title characters alone is mentioned in several earlier plays: The Merchant of Venice (“in such a night / Troilus methinks mounted the Troyan walls / And sighed his soul toward the Grecian tents, / Where Cressid lay that night”; 5.1.3-6) The Merry Wives of Windsor (“Shall I Sir Pandarus of Troy become, / And by my side wear steel?”; 1.3.65-6) Much Ado About Nothing (“Troilus, the first employer of panders, [was] never so truly turned over and over as my poor self in love”; 5.2.25-9) Henry V (“to the spital go, / And from the powdering tub of infamy / Fetch forth the lazar kite of Cressid’s kind, / Doll Tearsheet”; 2.1.69-72) As You Like It (“Troilus had his brains dashed out with a Grecian club; yet he did what he could to die before, and he is one of the patterns of love”; 4.1.85-8) Twelfth Night (“I would play Lord Pandarus of Phrygia, sir, to bring a Cressida to this Troilus… Cressida was a beggar”; 3.1.49-53) Troilus and Cressida the history play? Proleptic treatment of the characters’ posthumous reputations: TROILUS. True swains in love shall in the world to come Approve their truths by Troilus. When their rhymes, Full of protest, of oath and big compare, Wants similes, […] ‘As true as Troilus’ shall crown up the verse, And sanctify the numbers. CRESSIDA. […] If I be false, or swerve a hair from truth, When time is old and hath forgot itself, […] Yea, let them say, to stick the heart of falsehood, ‘As false as Cressid.’ PANDARUS. […] If ever you prove false one to another, since I have taken such pain to bring you together, let all pitiful goers-between be called to the world's end after my name: call them all panders. (3.2.169-98) Troilus and Cressida the history play? Similarly proleptic treatment of the war leaders: ULYSSES. Sir, I foretold you then what would ensue. My prophecy is but half his journey yet; For yonder walls, that pertly front your town, Yond towers whose wanton tops do buss the clouds, Must kiss their own feet. (4.7.100-4) Shakespeare’s source for this plot (though not the Cressida plot) was Homer’s Iliad… This account of Hector and Achilles’ final battle from The Iliad (as translated by George Chapman shortly after the publication of Shakespeare’s play) gives a sense of how radical Shakespeare’s treatment of his source was: “Thus forth his [Hector’s] sword flew, sharp and broad, and bore a deadly weight, With which he rushed in. And look how an eagle from her height Stoops to the rapture of a Iamb, or cuffs a timorous hare: So fell in Hector, and at him Achilles; his mind’s fare Was fierce and mighty; his shield cast a sun-like radiance, Helm nodded, and his four plumes shook; and, when he raised his lance, Up Hesperus rose ’mongst th’ evening stars. His bright and sparkling eyes Looked through the body of his foe, and sought through all that prise The next way to his thirsted life. Of all ways, only one Appeared to him; and that was where th’ unequal winding bone That joins the shoulders and the neck had place, and where there lay The speeding way to death; and there his quick eve could display The place it sought, even through those arms his friend Patroclus wore When Hector slew him. There he aimed, and there his javelin tore Stern passage quite through Hector’s neck…” (Book 22, lines 269-83) The goddess Athena helps Achilles to defeat Hector in Homer; as in Shakespeare, Achilles goes on to dishonour Hector’s corpse. Troilus and Cressida the history play? Indeed, Shakespeare seems to present a radically cynical version of a well-known story: Ajax and Achilles bragging and squabbling over status; Achilles lounging around watching Patroclus do impressions; Ulysses and Nestor manipulating their compatriots’ pride and insulting them behind their backs; Ajax’s complete absence of self-awareness; Achilles’ dishonourable murder of the unarmed Hector. Consider this deliberate misquotation of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus: TROILUS. Is she worth keeping? Why, she is a pearl Whose price hath launched above a thousand ships And turned crowned kings to merchants. (2.2.80-2) Troilus and Cressida the history play? Is Thersites a Falstaff-like character, hovering on the margins of official history? He gets only the briefest of mentions in The Iliad: “A most disordered store Of words he foolishly poured out, of which his mind held more Than it could manage; anything with which he could procure Laughter, he never could contain. He should have yet been sure To touch no kings; t’ oppose their states becomes not jesters’ parts. But he the filthiest fellow was of all that had deserts In Troy’s brave siege. He was squint-eyed, and lame of either foot; So crookbacked that he had no breast; sharp-headed, where did shoot (Here and there ’spersed) thin, mossy hair.” (Book 2, 181-9) Troilus and Cressida the history play? In Shakespeare, Thersites presents a subversively cynical view of this traditionally heroic subject: He calls the “whole camp” of the Greeks “those that war for a placket” [the slit at the top of a woman’s petticoat] (2.3.19) and accuses both Ajax and Achilles of stupidity and brute force throughout the play; He tells Ajax and Achilles that Ulysses and Nestor “yoke you like draught-oxen and make you plough up the war” (2.1.107-8); By the end, he is convinced that “the policy of those crafty swearing rascals – that stale old mouse-eaten dry cheese Nestor and that same dog-fox Ulysses – is not proved worth a blackberry” (5.4.8-11); His frequent curses suggest not just cynicism, but seething anger at the fact of this war over “a whore and a cuckold” (2.3.71). Troilus and Cressida the history play? Diomedes (not an especially comic character) expresses a similarly jaundiced view of the war, comparing Paris and Menelaus: DIOMEDES. …Both merits poised, each weighs nor less nor more, But he as he: the heavier for a whore. PARIS. You are too bitter to your countrywoman. DIOMEDES. She’s bitter to her country. Hear me, Paris. For every false drop in her bawdy veins A Grecian’s life hath sunk; for every scruple Of her contaminated carrion weight A Trojan hath been slain. Since she could speak She hath not given so many good words breath As, for her, Greeks and Trojans suffered death. (4.1.67-76) Troilus and Cressida the tragedy? An Aristotelian tragedy sees a high-born, largely good protagonist brought to adversity in a pattern of hamartia, anagnorisis and peripeteia, bringing about catharsis. It is easiest to see this pattern in Troilus and Cressida through the figure of Hector. For the Greeks, Hector’s death at the end of the play heralds the imminent fall of Troy (though at the play’s conclusion the Trojans remain undefeated). Hector’s hamartia? Hector starts the debate scene with a position it’s hard to disagree with: He maintains his position as Troilus and Paris argue that surrendering Helen would be dishonourable, but concludes: HECTOR. Let Helen go. […] If we have lost so many tenths of ours To guard a thing not ours – nor worth to us, Had it our name, the value of one ten – What merit’s in that reason which denies The yielding of her up? (2.2.16-24) HECTOR. … Hector’s opinion Is this in way of truth – yet ne’ertheless, My spritely brethren, I propend to you In resolution to keep Helen still; For ’tis a cause that hath no mean dependence Upon our joint and several dignities. (2.2.187-92) Hector’s hamartia? The scene’s discourse seems to recognise that there is nothing inherently honourable about this course of action, but that it is honourable because people think it is honourable: TROILUS. What is aught, but as ’tis valued? (2.2.51) TROILUS. She is a theme of honour and renown, A spur to valiant and magnanimous deeds… (2.2.198-9) The scene with Andromache and Cassandra just before the climax (5.3) re-focuses our attention on Hector’s decisionmaking, in which he re-iterates his decision to fight on the grounds of his honour, despite Cassandra’s predictions (failing to heed Cassandra’s warnings is, of course, a trope of classical tragedy). Troilus and Cressida the tragedy? The Folio title, however, suggests that this is not Hector’s tragedy but the lovers’. Shakespeare’s main source for this plot was Geoffrey Chaucer’s poem ‘Troilus and Criseyde’ (c. 1385). Chaucer presents the tale as one of star-crossed lovers, or “fatal destiny”, and calls the book “little mine tragedy”. Chaucer’s poem finishes by noting that Troilus was slain in battle by Achilles, concluding with a description of Troilus’s ghost looking down at the earth from heaven, and an exhortation to young people to eschew “worldly vanity” and love Christ (Chaucer does not tell us what became of Cressida). Troilus and Cressida the tragedy? The Scottish poet Robert Henryson (c.1425-c.1500) wrote a sequel of sorts, ‘The Testament of Cresseid’: He also describes it as a “tragedy”. He describes reading Chaucer’s ‘Troilus and Criseyde’, and then “a second book where I found the fatal destiny of Cresseid, who ended wretchedly”. Abandoned by Diomedes, Cressida “wandered aimlessly and, some men say, she became a court whore”. Cressida is “oppressed with pain, torment, and incurable sickness”, and compelled “to survive as a common beggar”. She becomes unrecognisable to Troilus, who passes her on his way back to the city (Troilus is still alive in Henryson’s version), and dies in poverty, broken-hearted. She begs the women of Troy and Greece to learn from her misery that beauty and honour are transient. Troilus and Cressida the tragedy? We know from the diary of Philip Henslowe that the Admiral’s Men produced a play called Troilus and Cressida by Henry Chettle and Thomas Dekker in 1599; a plot outline for what is probably this play survives at the British Library. It includes a scene with the stage direction “Enter Cressida, with beggars”, suggesting that Shakespeare’s audience may have been familiar with Henryson’s version of the story. Troilus and Cressida the tragedy? Central plot as a twist on Romeo and Juliet? Both plays open with a lovesick hero confiding in a friend; Both heroes soliloquise in an orchard as they anticipate meeting the heroine; Both describe their love at this moment with metaphors of flight: “From Cupid’s shoulder pluck his painted wings / And fly with me to Cressid” (T&C, 3.2.13-14); “With love’s light wings did I o’erperch these walls, / For stony limits cannot hold love out” (R&J, 2.1.108-9); Both heroines blush during the scene that follows; Both heroines are sceptical of the hero’s overblown romantic vows, and worry that they are acting too quickly, but confess their love all the same; Both plays have an aubade scene immediately after the couple’s first and only night together, in which the parting lovers lament the shortness of the night and the singing of the lark. But Shakespeare’s play does not depict the death of either of its title characters – even though accounts of both deaths were available to him in his sources, and he refers to Troilus’ death and Cressida’s beggary in other plays. Why? References Bakhtin, Mikhail (1965) Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Bergson, Henri (1900) ‘Laughter’, in Wylie Sypher (1956) Comedy, New York: Doubleday Anchor, 59190. Escolme, Bridget (2005) Talking to the Audience: Shakespeare, performance, self, London and New York: Routledge.