Lecture 6 (4-20-00)

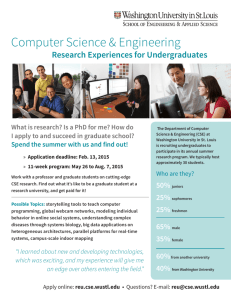

advertisement

Programming Paradigms and

Algorithms

W+A 3.1, 3.2, p. 178, 6.3.2, 10.4.1

H. Casanova, A. Legrand, Z. Zaogordnov, and F. Berman, "Heuristics for

Scheduling Parameter Sweep Applications in Grid Environments",

Proceedings of the 2000 Heterogeneous Computing Workshop

(http:apples.ucsd.edu)

CSE 160/Berman

Parallel programs

• A parallel program is a collection of tasks

which can communicate and cooperate to

solve large problems.

• Over the last 2 decades, some basic

program structures have proven successful

on a variety of parallel architectures

• The next few lectures will focus on parallel

program structures and programming issues.

CSE 160/Berman

Common Parallel Programming

Paradigms

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Embarrassingly parallel programs

Workqueue

Master/Slave programs

Monte Carlo methods

Regular, Iterative (Stencil) Computations

Pipelined Computations

Synchronous Computations

CSE 160/Berman

Embarrassingly Parallel

Computations

• An embarrassingly parallel computation is one

that can be divided into completely independent

parts that can be executed simultaneously.

– (Nearly) embarrassingly parallel computations are those

that require results to be distributed, collected and/or

combined in some minimal way.

– In practice, nearly embarrassingly parallel and

embarrassingly parallel computations both called

embarrassingly parallel

• Embarrassingly parallel computations have

potential to achieve maximal speedup on parallel

platforms

CSE 160/Berman

Example: the Mandelbrot

Computation

• Mandelbrot is an image computing and display

computation.

• Pixels of an image (the “mandelbrot set”) are

stored in a 2D array.

• Each pixel is computed by iterating the complex

function

z k 1 z k c

2

where c is the complex number (a+bi) giving the

position of the pixel in the complex plane

CSE 160/Berman

Mandelbrot

• Computation of a single pixel:

z k 1 z k c

2

z k 1 ( ak bk i ) 2 (creal cimagi )

( ak bk creal ) ( 2ak bk cimag )i

2

2

• Subscript k denotes kth interation

• Initial value of z is 0, value of c is free parameter

• Iterations are continued until the magnitude of z is greater than 2

(which indicates that eventually z will become infinite) or the

number of iterations reaches a given threshold.

• The magnitude of z is given by

2

2

zlength a b

CSE 160/Berman

Sample Mandelbrot Visualization

• Black points do not go to infinity

• Colors represent “lemniscates” which are basically sets of

points which converge at the same rate

• http://library.thinkquest.org/3288/myomand.html lets you

color your own mandelbrot set

CSE 160/Berman

Mandelbrot Programming Issues

• Mandelbrot can be structured as a data parallel

computation so the same computation is performed on all

pixels, except with different complex numbers c.

– The difference in input parameters result in different number of

iterations (execution times) for the computation of different pixels.

– Mandelbrot is embarrassingly parallel – computation of any two

pixels is completely independent.

• Computation is generally visualized in terms of display

where pixel color corresponds to the number of iterations

required to compute the pixel

– Coordinate system of Mandelbrot set is scaled to match the

coordinate system of the display area

CSE 160/Berman

Static Mapping to Achieve Performance

• Pixels generally organized into blocks and the blocks are

computed on processors

• Mapping of blocks to processors can greatly affect

application performance

• Want to load-balance the work of computing the values of

the pixels across all processors.

CSE 160/Berman

Static Mapping to Achieve Performance

• Good load-balancing strategy for Mandelbrot is to

randomize distribution of pixels

Block decomposition

can unbalance load by

clustering long-running

pixel computations

Randomized decomposition

can balance load by

distributing long-running

pixel computations

CSE 160/Berman

Dynamic Mapping: Using Workqueue to

Achieve Performance

• Approach:

– Initially assign some blocks to processors

– When processors complete assigned blocks, join queue to wait

for assignment of more blocks

– When all blocks have been assigned, application concludes

Processors

obtain block(s)

from front of

queue

Processors

Blocks

Processors

perform work

and get more

block(s)

CSE 160/Berman

Workqueue Programming Issues

• How much work should be assigned initially to

processors?

• How many blocks should be assigned to a given

processor?

– Should this always be the same for each processor? for

all processors?

• Should the blocks be ordered in the workqueue in

some way?

• Performance of workqueue optimized if

– Computation of each processor amortizes the work of

obtaining the blocks

CSE 160/Berman

Master/Slave Computations

• Workqueue can be implemented as a master/slave

computation

– Master directs the allocation of work to slaves

– Slaves perform work

• Typical M/S Interaction

– Slave

While there is more work to be done

Request work from Master

Perform Work

(Provide results to Master)

– Master

While there is more work to be done

(Receive results and process)

Provide work to requesting slave

CSE 160/Berman

Flavors of M/S and Programming

Issues

• “Flavors” of M/S

– In some variations of M/S, master can also be a slave

– Typically slaves do not communicate

– Slave may return “results” to master or may just request more

work

• Programming Issues

– M/S most efficient if granularity of tasks assigned to slaves

amortizes communication between M and S

– Speed of slave or execution time of task may warrant non-uniform

assignment of tasks to slaves

– Procedure for determining task assignment should be efficient

CSE 160/Berman

More Programming Issues

• Master/Slave and Workqueue may also be used

with “work-stealing” approach where

slaves/processes communicate with one another to

redistribute the work during execution

– Processors A and B perform computation

– If B finishes before A, B can ask A for work

A

CSE 160/Berman

B

Monte Carlo Methods

• Monte Carlo methods based on the use of

random selections in calculations which

lead to the solution of numerical and

physical problems.

– Term refers to similarity of statistical

simulation to games of chance

• Monte Carlo simulation consists of multiple

calculations, each of which utilizes a

randomized parameter

CSE 160/Berman

Monte Carlo Example:

Calculation of P

• Consider a circle of unit radius inside a

square box of side 2

1

• The ratio of the

area of the circle

to the area of the

square is

1 1

22

4

CSE 160/Berman

Monte Carlo Calculation of P

• Monte Carlo method to approximating :

– Randomly choose a

sufficient number of

points in the square

– For each point p,

determine if p is in

the circle or the square

– The ratio of points in

the circle to points in

the square will provide

an approximation of

CSE 160/Berman

4

M/S Implementation of Monte

Carlo Approximation of P

• Master code

– While there are more points to calculate

• (Receive value from slave; update circlesum or boxsum)

• Generate a (pseudo-)random value p=(x,y) in the bounding box

• Send p to slave

• Slave code

p

– While there are more points to calculate

• Receive p from master

• Determine if p is in the circle or the square

2

2

[ check to see if x y 1 ]

• Send p’s status to master; ask for more work

CSE 160/Berman

y

x

Using Monte Carlo for a Large-Scale

Simulation: MCell

• MCell = General simulator for

cellular microphysiology

• Uses Monte Carlo diffusion and

chemical reaction algorithm in 3D

to simulate complex biochemical

interactions of molecules

– Molecular environment represented as

3D space in which trajectories of

ligands against cell membranes tracked

• Researchers need huge runs to

model entire cells at molecular

level.

– 100,000s of tasks

– 10s of Gbytes of output data

– Will ultimately perform execution-time

computational steering , data analysis

and visualization

MCell Application Architecture

• Monte Carlo simulation

performed on large

parameter space

• In implementation,

parameter sets stored in

large shared data files

• Each task implements an

“experiment” with a

distinct data set

• Ultimately users will

produce partial results

during large-scale runs

and use them to “steer”

the simulation

MCell Programming Issues

• Application is nearly embarrassingly parallel and

can target either MPP or clusters

– Could even target both if implementation were

developed in this way

• Although application is nearly embarrassingly

parallel, tasks share large input files

– Cost of moving files can dominate computation time by

a large factor

– Most efficient approach is to co-locate data and

computation

– Workqueue does not consider data location in allocation

of tasks to processors

CSE 160/Berman

Scheduling MCell

• We’ll show several ways that MCell can be scheduled on a

set of clusters and compare execution performance

Cluster

storage

network

links

User’s host

and storage

MPP

Contingency Scheduling Algorithm

•

Allocation developed by dynamically generating a Gantt chart for

scheduling unassigned tasks between scheduling events

•

Basic skeleton

Create a Gantt Chart G

3.

For each computation and file transfer

currently underway, compute an estimate

of its completion time and fill in the

corresponding slots in G

4.

Select a subset T of the tasks that have

not started execution

5.

Until each host has been assigned

enough work, heuristically assign

tasks to hosts, filling in slots in G

6.

Implement schedule

1

2

1

2

1

2

Scheduling

event

Scheduling

event

G

Computation

2.

Resources

Computation

Compute the next scheduling event

Time

1.

Network

Hosts

Hosts

links (Cluster 1) (Cluster 2)

MCell Scheduling Heuristics

• Many heuristics can be used in the contingency scheduling algorithm

– Min-Min [task/resource that can complete the earliest is assigned first]

min i {min j { predtime(taski , processor j )}}

– Max-Min [longest of task/earliest resource times assigned first]

ma x i {min j { predtime(taski , processor j )}}

– Sufferage [task that would “suffer” most if given a poor schedule assigned first]

ma x i , j { predtime(taski , processor j )} next max i , j { predtime(taski , processor j )}

– Extended Sufferage [minimal completion times computed for task on

each cluster, sufferage heuristic applied to these]

ma x i , j { predtime(taski , cluster j )} next max i , j { predtime(taski , cluster j )}

– Workqueue [randomly chosen task assigned first]

Which heuristic is best?

• How sensitive are the scheduling heuristics to the

location of shared input files and cost of data

transmission?

• Used the contingency scheduling algorithm to compare

–

–

–

–

–

Min-min

Max-min

Sufferage

Extended Sufferage

Workqueue

• Ran the contingency scheduling algorithm on a

simulator which reproduced file sizes and task run-times

of real MCell runs.

CSE 160/Berman

MCell Simulation Results

•

Comparison of the performance of scheduling heuristics when it is up to

40 times more expensive to send a shared file across the network than it is

to compute a task

•

“Extended sufferage” scheduling heuristic takes advantage of file sharing

to achieve good application performance

Workqueue

Sufferage

Max-min

Min-min

XSufferage

Additional Programming Issues

• We almost never know completely accurately what the

runtime will be

• Resources may be shared

• Computation may be data dependent

• Task execution time may be hard to predict

• How sensitive are the scheduling heuristics to inaccurate

performance information?

– i.e., what if our estimate of the execution time of a task on a

resource is not 100% accurate?

CSE 160/Berman

MCell with a single scheduling event and task

execution time predictions with between 0% error

and 100% error

Same results with higher frequency of

scheduling events