What is code switching?

advertisement

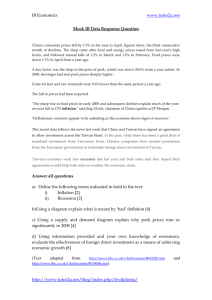

Code switching in Taiwan and its implications for Greater Chinese communities Jennifer M. Wei English Department Soochow University Taipei, Taiwan 11102 Wei_jennifer@hotmail.com Outline 1. What is code switching? 2. Why do people switch codes? 3. How do they switch? 4. Different approaches to studies of code switching: --psychology --cognitive science --function 5. Examples and interviews 6. Using Taiwan’s political discourse to argue for a translinguistics approach to code switching 7. Implications for Greater Chinese communities What is code switching? 1. 2. 3. 4. Speakers use more than one language in a discourse unit (an exchange, a sentence, a paragraph). “Language” here is defined loosely -- it can be two different languages such as French and German, or varieties of a language family such as Mandarin and Cantonese, or a variety of language styles (such as a mix of different registers). A related but different term, code mixing, refers to hybridization in a shorter and fixed exchange rather than an active movement from one language to another in a discourse. Code mixing suggests that the speaker is mixing up codes indiscriminately, perhaps because of incompetence, whereas code switching refers to a more active manipulation of the symbolic and social meanings of a language choice. An example from Singaporean English http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aoZIF59Qsiw&NR=1 Examples of code switching from pop commercials in Taiwan (switching between Mandarin and Taiwanese) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kuCuzcTa33s (cough syrup) Shopping channel http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbIFZQz3-k8 (worship) How do people switch codes, and why? 1. Code switches occur at any linguistic boundary (sentence initial, sentence final, between words). 2. Speakers actively inject meanings into conversation by adding varieties. 3. In “situational switching,” speakers code switch according to factors (topics, situations, participants). 4. Examples: using more formal codes such as English, Japanese or Mandarin to signal professionalism and authority, or switching to a more “intimate” code such as Cantonese, Hakka, or Taiwanese to signal solidarity or group identity. 5. More rarely, a skillful code switch can operate like a metaphor to enrich communication without any change in the situation (no change of topic, no new participants, no change of scene). 6. Responses from people who switch codes http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a2LUULzo5JU Metaphorical switching (1) An example involving English and Samoan is taken from Holms, 1992, pp. 49-50. (Words originally spoken in Samoan are in CAPITALS; the rest is English.) Alf is 55 and overweight. He is talking to a fellow Samoan at work about his attempt to go on a diet. My doctor told me to go on a diet. She said I was overweight. So I tried. BUT IT WAS SO HARD. I’D KEEP THINKING ABOUT FOOD ALL THE TIME. Even when I was at work. And in bed at night I’D GET DESPERATE. I COULDN’T GET TO SLEEP. SO I’D GET UP AND RAID THE FRIDGE. THEN I’D FEEL GUILTY AND SICK AND WHEN I WOKE UP NEXT DAY I WOULD BE SO DEPRESSED because I had to start the diet all over again. The doctor wasn’t sympathetic. She just shrugged and said. ‘Well it’s your funeral!’ Metaphorical switching (continued) In the example, the speaker draws on two languages to express ambivalent feelings about the topic he is discussing. There is no exact one-to-one correspondence, but it is possible to see that in general, personal feelings are expressed in Samoan while English is used for referential content such as “My doctor told me to go on a diet.” Samoan expresses shame and embarrassment (“I’d get desperate”, “I would be so depressed”.) Rational Choice Theory and Markedness Model (From Myers-Scotton and Bolonyai, Language in Society 30:1 (2001) p. 23 RC theory is based on the assumption about human cognition that actors are oriented to seek optimality of an interpersonal nature in their actions, including their linguistic choices. The overall assumption is that the way speakers choose to speak reflects their cognitive calculations to present a specific persona that will give them the best “return” in their interactions with others, in whatever ways are important to them and are rationally grounded. Limitations for RC Theory Three limitations of this framework as a model of linguistic choices (and limitations of RC theory in general) are worth emphasizing. First, social mechanisms such as rationality allow us to explain, but do not necessarily predict, future choices individuals will make. Second, an RC model does not necessarily produce quantitative evidence. Third, such models do not claim that actors always make what others (e.g. analysts) might consider to be rationally based choices, nor do they claim that actors always make the best choices from an objective standpoint. As Elster puts it, “Rational choice models are subjective through and through . . .To be rational does not mean that one is invariably successful in realizing one’s aims: it means only that one has no reason to think that one should have acted differently, given what one knew (and could have known) at the time” (1997:761; italics in original). Markedness Model The MM presupposes that as part of their general cognitive architecture all speakers have a markedness evaluator. This abstract component underlies the capacity to conceptualize markedness. Specifically as a sociolinguistic construct, markedness refers to the capacity to develop the following three abilities. (i) Most important is the perception that relevant linguistic choices for a specific interaction type fall along a multidimensional continuum from more socially unmarked to more marked. (ii) In addition, speakers learn to recognize that the markedness ordering of choices is dynamic; it depends on the specific interaction type, as well as on how the individual interaction develops. (iii) Finally, speakers develop the ability to provide relevant interpretations for all choices, marked as well as unmarked, given the interaction type. Markedness Model (cont.) (b) To develop these abilities requires exposure to the use of both unmarked and marked choices in actual community discourse. Input from experience empowers the markedness evaluator to set up readings of markedness as a guide for speakers to prune multiple options. That is, the evaluator indicates which choices are relatively more or less marked for the interaction type. (c) In sum, then, the markedness evaluator is a deductive device (it makes predictions about relative markedness) that operates on inductively assembled data. What the markedness evaluator offers is not a set of rules, but rather a process for evaluating potential choices. (d) The interpretations that speakers attach to linguistic choices have to do with the speaker’s projection of his/her own persona and relations with other participants. Thus, any choice a speaker makes is perceived as indexing a desired Rights and Obligations (RO) set between participants. All participants interpret a choice against the backdrop of those choices that index the more unmarked RO sets for a specific interaction type. As a corollary, this means that they also recognize some choices as indexing more marked RO sets. An example For example, the choice of Kristóf, a Hungarian-and-English speaking boy living in the United States. To speak only Hungarian at the dinner table would be an index of what his parents might prefer as the unmarked RO set for family interactions in his home. Under this RO set, children are compliant with their parents’ wishes to keep their ethnicity salient through linguistic means rather than assimilating fully to the dominant culture. If Kristóf switches between Hungarian and English, this might index a somewhat less preferred RO set, from the parents’ point of view. However, if Kristóf should insist on speaking only English at the family dinner table, this move would index a marked RO set from the point of view of family norms. Under such an RO set, Kristóf would be asserting his independence from familial control and possibly even his “defection” to the dominant (American) culture. What Taiwan offers to the study of code switching (but first, a detour to Canada) 1. Monica Heller tells us that in Montréal and Quebec , the French and English have a history of power struggle for resources and representation. 2. Two patterns of code switching—both casting light on the situation in Taiwan—arise. 3. For aspiring professionals, making a language choice can be a managerial skill to make friends and appease foes in contexts where historical animosities may prevail. 4. Secondly, making such a choice can be seen as a political strategy to demand rights and representation. Why and how Taiwan politicians exploit different languages First, some history to explain why Taiwan’s language scene differs from that of other Chinese communities. Twice in a hundred years a non-indigenous tongue was imposed as a “national” language. First came Japanese during the Japanese occupation (1895-1945), and then came Mandarin during the heyday of KMT rule (1945-1987). Modernization in both Japan and China, combined with an island backlash against nationalistic language policies and a rising Taiwanese consciousness, inspired Taiwan language reforms in the 1930s and 1990s. Why and how Taiwan politicians exploit different languages (continued) In the most recent case, with ethno-linguistic consciousness surging and democracy gaining, politicians found they could connect to different constituencies by switching between languages. They could address the unspeakable: Taiwan’s ambiguous national status. They could allude to past wrongs suffered under a Mandarin-only language policy and a China-center identity. Mandarin/Taiwanese juxtaposition: Example 1 (Tai-yu in CAPITALS; the rest in Mandarin) Zhonghua renmin gongheguo burang women miaoli li zi-zhen qu, CHIT8-TIUN1 HO2- PAI5 PIAN3SENG5 A-PIN2-AH BEH4 LIA7-KHI3 TAI5, CHIN1 U7 CHHA7 HIA1 CHE7? (Then-President Chen Shui-bian, campaigning in Miaoli, responding to criticism over his choice of APEC representative. Era News10/27/01) Trans: The PRC (People’s Republic of China) won’t let our Miaoli adviser Li attend [APEC]. A GOOD CARD WAS TURNED INTO A-BIAN’S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT. DID IT REALLY MAKE THAT MUCH DIFFERENCE? (Example 1 continued) Symbolic acts of identity Who is responsible for not sending the right representative to APEC? An explanation from the Rational Choice Model (Bolonyai and Myers-Scotton 2001) Example 2 (Mandarin is in CAPITALS; the rest is Tai-yu) An opposition presidential candidate, Peng Ming-min, responds to a question about top priorities for a president in the 21st century. Excerpt: chit9 ma2 tai7 oan5 e7 sia3 hoe7, si7 chit8 ko3 be5-sit tek sia7hoe7, MISHI DE SHEHUI, hun7-to lang5 tou chai7 mng7, dau2 de che ko2 cheng2 hu2, be2 cha2 gun2 kau2 siaN mih hong7 hiong3? sou i chai3 che ko2 gi7 bun3 e7, jim3 ho5 chiong7 lai5 e7 chong thong2, siang3 kin7 pun2 e7 lim3 bu7 u3 liong ko3: te7 chit8 kok9 ka e7 toa7 hong7 hiong3, gun be2 kiaN7 kau2 to ui7, be2 kong tek9 hun3 chheng7 chho ka3 kok9 bin5 liau kai2; WOMEN SHI SHEI? TAIWAN SHI SHENME? WEISHENME WOMEN YAO ZAI ZHELI? WOMEN YAO XIANG NALI ZOU? che tio3 si3 siang3 tiong3 iau2 e, pau7 koat9 kok9 ka e7 teng3 ui7. Trans: Contemporary Taiwan is a lost society. A lot of people are wondering where this government is taking us. In this uncertainty lie… fundamental tasks for the future president: First, he has to point out clearly to the people a direction for the country. WHO ARE WE? WHAT IS TAIWAN? WHY ARE WE HERE? WHERE ARE WE GOING? This is the most important task, involving as it does the identity of the nation. (Example 2 continued) Who are we? Why are we here? Where do we want to go? An explanation from M. Bakhtin’s (1981)Translinguistics In this example, by using both Mandarin and Taiyu, Peng is addressing different constituents with conflicting ideologies manifested in Mandarin (official and authoritative) and Taiyu (language of democracy and the people). In their metonymic associations, Mandarin further suggests Chinese polity and Tai-yu Taiwanese polity; the one the voice of unification, the other bespeaking separation. The interaction becomes not a simple disruption, but a translinguistics battlefield upon which two ways of speaking struggle for dominance. Bakhtin’s translinguistics: voices and dialogue Several concepts in Bakhtin (1981) are useful to understanding how a language choice can evoke meanings beyond here and now situational meanings and rational calculations of rights and responsibilities. The identification of “voices” and an account of the theoretical possibilities for their juxtaposition are major concerns in translinguistics. The choice of a code (language) in code switching can be seen as just one aspect of the many ways in which voices can differ from each other (Hill and Hill 1986, p. 388). Bakhtin’s translinguistics: a new approach to codeswitching Translinguistics allows us to stress the fluidity and possibility of different “voices” entering a stream of words from the speaker. This contrasts with the traditional code switching model, which admits the pragmatic function of a language choice but still emphasizes the coherence of the language structure. In the traditional model, we identify constraints and rules of when and why a certain switch cannot occur in a sentence, but we are denied the chance of allowing conflicting analyses of the same code or considering the possibility that the speaker is accommodating seemingly opposed ideologies. An implication for Greater Chinese communities: from nationalism to pragmatism 1. The use of Tai-yu to construct and challenge the Mandarin-only and China-center policies is unique in Taiwan since no other Chinese communities experienced twice-nationalistic language policies in the last century. 2. Since the 1980s, a pluralistic view on language and identity has been brought to the debate, and multilingualism has more or less been practiced. 3. Given Taiwan’s ambiguous national status, it might be wise not to implement an institutionalized multilingualism such as Canada’s. 4. China has been very careful not to use the language issue to goad authorities across the Strait. In fact, a bidialectism (where Mandarin is encouraged but the local dialect not discouraged) has been practiced on the mainland. In Summary Code switching is a very prevalent language phenomenon. It can be used for various pragmatic and strategic purposes. The meaning of a code choice depends on its situational interpretation as well as metaphorical meaning. Taiwan’s politicians have helped bring the use of code switching to a translinguistics level where we can tap into history and contemplate the future of what a language choice can mean. Some Final Words Most people who are bilingual or multilingual code switch. Most people deny their use of more than one code (as seen from the college students in China, Hong Kong and Singapore). The Internet has added a surging force to the immediacy and prevalence of code switching. A twice nationalistic language policy in the 20th century has made Taiwan a unique place for the study of code switching. What will be our language choice in the 21st century? References Shanghaiese and Mandarin http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9AmlH_URY4&feature=fvsr http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayFulltext?type=1&fid=67422 &jid=&volumeId=&issueId=01&aid=67421&bodyId=&membershipNumb er=&societyETOCSession= (From Myers-Scotton and Bolonyai (2001), Language in Society 30:1 (2001) Acknowledgement: This presentation was initially prepared as a speech at the Graduate institute of Teaching Chinese as a Second Language at Kainan University in Taiwan. Thanks are due to Professor Dennis Schilling for the invitation and to the participants for a warm reception and the questions and comments.