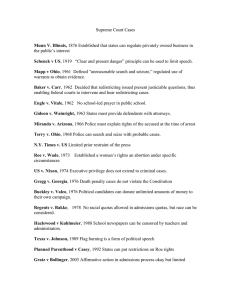

Chapter 2 The Network of Law: General Considerations “Justice

advertisement