the great financial crisis

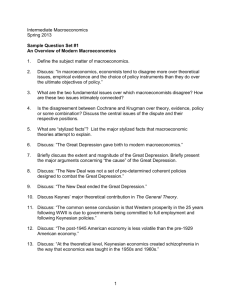

advertisement

THE GREAT FINANCIAL CRISIS HOW HAS IT CHANGED THE TEACHING OF ECONOMICS? THE DEMAND FOR BETTER ECONOMISTS HASN’T CHANGED • IN THE aftermath of the Great Depression there were important changes in the way economics was both studied and taught, but it may be over-optimistic to think that the current financial crisis will involve anything like the same degree of re-evaluation of the profession's habits. Most importantly, the Roosevelt administration vastly increased the numbers of economists employed by the federal government . The expansion of job opportunities also created an incentive to create and remodel university courses to meet this demand; ideas and incentives complemented one another. SECONDARY TEACHERS MUST LEAD THE CHARGE • There are severe financial stresses on universities everywhere that will cast doubt on their ability or willingness to initiate untried yet potentially more relevant teaching methods. THE ECONOMIC FEAR TO FEAR IS FEAR ITSELF • We have the same workforce and physical capital today as in 2007. • Watching one financial megalith after another bite the dust and one politician after another scream, "The depression is coming, the depression is coming", terrified the private sector. • Too many textbooks present old-time Keynesian solutions, viewing this as a problem of inflexible wages and prices. It's not. And the solution is not more spending, but taking the fear out of the economic equation. COMMUNICATE THE POSSIBILITY OF MULTIPLE EQUILIBRIA • If employers fear significantly depressed economic activity, they will sit on their hands and produce that outcome. • If demanders fear their next paycheck will be their last and that their assets will drop in value, they will stop buying and sell their assets and, thus, instigate their prediction. • If lenders fear their borrowers are no longer trustworthy, they'll set their lending rates higher and ensure that only desperate borrowers request loans. ECONOMIC HISTORY WILL BE AT THE HEART OF ECONOMIC INSTRUCTION • One of the stranger myths about the recent financial crisis is that no one saw it coming. • A lot of economists saw it coming, and for years had been writing with dread about the growing global imbalances. • The mass of enthusiasts targeted these economists as doomsayers and party poopers. • Financial history does not vary much— there is little about the Roman real estate crisis of 33 AD, for example, that isn’t thoroughly familiar to us today. BANK RUNS CAN OCCUR EVEN WHEN INDIVIDUAL DEPOSITORS ARE INSURED • When institutional lenders all abandon an investment bank simultaneously, the bank experiences a liquidity crisis that has much in common with a classic bank run. • In a modern bank run, the actors rushing for the exits are institutional lenders not individual depositors. • Liquidity and financial intermediation have emerged as key topics in macroeconomics and finance. THE CRISIS HAS BROUGHT TO THE FORE THE COMPLEX CONNECTIONS AMONG MARKETS, GOVERNMENT AND SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC POLICIES. • The basic principles of economics have not changed—people and firms respond to incentives; demand and supply determine the relative prices of goods, services and even money itself; markets generally allocate resources well and deliver welfare-improving outcomes. • The notion that markets are always efficient, can be left to themselves and are self-correcting is no longer tenable. • Markets do eventually correct but, if allowed free rein, can get so far out of line that the corrections take the form of collapses that can be very painful. MACROECONOMICS IS AT AN HISTORIC CROSSROADS • Macroeconomics is in flux relative to the consensus view that seemed to be forming pre-2007. • It is hard to know what macroeconomics will look like in 20 years. • Today's students have an opportunity to take part in this creative destruction. That prospect is helping to get many new students excited about macroeconomics.