Psychological Dispositions and Political Preferences across Hard

advertisement

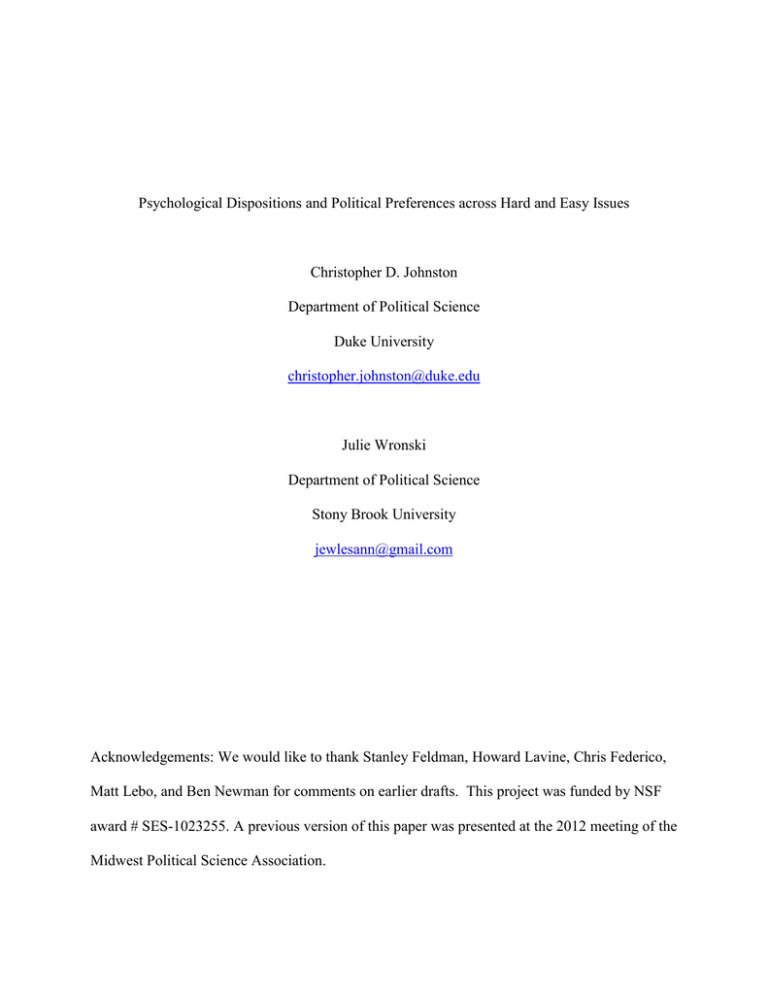

Psychological Dispositions and Political Preferences across Hard and Easy Issues Christopher D. Johnston Department of Political Science Duke University christopher.johnston@duke.edu Julie Wronski Department of Political Science Stony Brook University jewlesann@gmail.com Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Stanley Feldman, Howard Lavine, Chris Federico, Matt Lebo, and Ben Newman for comments on earlier drafts. This project was funded by NSF award # SES-1023255. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2012 meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association. Abstract A wealth of theoretical and empirical work now suggests that ideological orientations in the mass public are, to a large extent at least, rooted in more basic psychological dispositions. Despite substantial diversity in theoretical language, a common theme emerges from a review of this literature which sees conservative political orientations as providing a “functional match” for citizens relatively high in needs to manage uncertainty and threat. Recent empirical research, however, suggests that (1) associations of needs with economic conservatism are substantially weaker than associations with social conservatism and ideological identification, and (2) that political sophistication plays an important role moderating the translation of needs into political preferences. The present paper extends this recent work in offering a theoretical model of the translation of these needs into political preferences across ideological domains. We argue that, when issues are hard, citizens delegate preference formation to trusted elite actors on the basis of matches between symbolic party imagery and needs for certainty and security. In other words, the influence of dispositions on ideology in difficult ideological domains is indirect and conditional on elite cues. We test this basic framework utilizing a national survey experiment, and explore its normative implications for social welfare provision in the United States. 2 INTRODUCTION A wealth of theoretical and empirical work now suggests that ideological orientations in the mass public are, to a large extent at least, rooted in more basic psychological dispositions (i.e. traits, chronic needs and goals, etc.). This research investigates the correlates of liberal and conservative orientations at levels ranging from single gene studies (Settle et al. 2010) to examinations of highly abstract personality traits (Carney et al. 2008; Gerber et al. 2010; Mondak 2010), and much in-between (e.g. Amodio et al. 2007; Hetherington and Weiler 2009; Jost et al. 2003; Oxley et al. 2008). Despite such diversity, a common theme emerges from a review of this literature which sees conservative political orientations as providing a “functional match” for citizens relatively high in needs to manage uncertainty and threat, or in other words, needs for certainty and security (Jost et al. 2003; Jost, Federico and Napier 2009; Thorisdottir and Jost 2011).1 Citizens high in these needs are expected to find conservative values and policies appealing, as they represent adherence to traditional values and long-standing institutions, and thus provide a time-tested source of stability and predictability in the social world. Conversely, citizens low in these needs, who are characterized by a relative preference for novelty and a general comfort with ambiguity and change, are attracted to the liberal side of the ideological spectrum, which represents institutional and moral innovation under the banner of equality and diversity (Jost et al. 2003). Conservative (versus liberal) political orientations have shown strong 1 It should be noted that while the focus of most work, especially in political science proper, has been on stable individual differences, there is nothing intrinsically “dispositional” about these processes. Indeed, research demonstrates that such needs can be induced temporarily, and that manipulations exert qualitatively similar effects on judgment. This suggests that measured individual differences are tapping into the “chronic” manifestation of more general psychological principles related to the accessibility of goals such as security and epistemic closure (see Higgins 1999; Kruglanski and Webster 1996; Thorisdottir and Jost 2011). The focus of the present paper is on chronic differences. 3 associations with a variety of indicators of epistemic and existential needs (see Jost et al. 2003), personality traits related to openness and rule-following (Carney et al. 2008; Gerber et al. 2010; Mondak 2010; Thorisdottir et al. 2007), and physiological indicators of threat sensitivity and uncertainty avoidance (Amodio et al. 2007; Oxley et al. 2008), all suggesting the utility of this theoretical paradigm. Nonetheless, recent empirical research suggests that the basic model connecting needs for certainty and security to political conservatism in a direct, or unconditional, fashion is too simple. First, while empirical work consistently finds strong associations between indicators of these needs and ideological identification, variation in the strength of associations is apparent across distinct ideological domains (e.g. social, economic). In particular, associations tend to be much stronger for social preferences and values than for economic preferences and values. Indeed, several studies find minimal or no associations of key psychological indicators to economic preferences (e.g. Carney et al. 2008; Chirumbolo et al. 2004; Feldman and Johnston 2009; Van Hiel and Mervielde 2004; Van Hiel, Pandelaere and Duriez 2004), or find that needs for security and certainty are associated with general economic liberalism or support for government intervention in the economic domain (Golec 2001; Johnston 2011; Thorisdottir et al. 2007). Second, a small set of recent studies both theorizes and finds empirically that the translation of psychological dispositions into political preferences and ideology may be conditional on political engagement, or exposure to elite discourse, and this may be particularly true for the economic domain. Federico and Goren (2009) find that the need for closure is more strongly associated with ideology among the politically sophisticated, and Federico et al. (2011) find that sophistication moderates the translation of authoritarianism into (anti-)egalitarianism. 4 Jost, Federico and Napier (2009) suggest a theoretical model which combines insights from both psychology and political science, arguing that ideological ideas can only resonate with psychological dispositions to the extent that citizens are aware of such ideas. According to this model, then, we should observe interactions between political attention and dispositions in predicting ideological orientations. The present paper seeks to add to this emerging line of research in two ways. First, we suggest that the “mixed model” of interactions between dispositions and political engagement is itself conditional on the issues and issue domains examined. Citizens do not always need to pay attention to politics in order to connect their dispositions to their preferences. We suggest that the classic distinction in political science between “easy” and “hard” issues is crucial to this dynamic (Carmines and Stimson 1980). When issues have readily accessible symbolic referents, translation should occur in a rather “direct” fashion, independent of exposure to elite cues and discourse. In contrast, for more technical issues, for which symbolic associations are typically constructed by elites, citizens are far more reliant on elite discourse (Pollock, Lilie and Vittes 1993). For these issues, then, we expect the mixed model to be far more applicable. While recognizing that the categorization of issues as “easy” or “hard” is both a somewhat subjective enterprise, and may often be applied on an issue-to-issue basis, we nonetheless argue that, on average, social issues (e.g. gay marriage, abortion) are easy issues, while economic issues (e.g. healthcare, financial regulation) are hard issues. We understand that this may not hold in an absolute fashion, but believe this scheme has face validity, and is true on average. This is important, because it represents a possible resolution to the asymmetry in support for theoretical expectations between the social and economic domains in recent research. 5 Second, we explore one potential theoretical pathway by which the mixed model may operate, namely, partisan delegation and cue-taking (Berinsky 2007; Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Sniderman 2012; Zaller 1992). We suggest that citizens may select elite delegates on the basis of matches between their dispositional profiles and the symbolic imagery of party conflict, which, in recent decades, has become far more cultural in content, thus resonating more strongly with needs for certainty and security.2 Hetherington and Weiler (2009) argue and demonstrate that such needs are now strongly associated with partisan affiliations in the U.S. public. If this is the case, then interactions of sophistication and dispositions may be picking up on a process which is relatively independent of the content of public policy. Rather, consistent with much empirical and theoretical research (e.g. Cohen 2003; Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen 2012; Lau and Redlawsk 2006; Rahn 1993; Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock 1991), citizens may be responding more to the partisan labels attached to the policies. While this surely would not rule out the importance of ideas in shaping dispositional constraint, it would suggest the potential for associations between dispositions and preferences to span the ideological spectrum, conditional on the nature of extant elite conflict. In other words, when issues are difficult, the association between needs for certainty and security and conservatism could be positive or negative, depending on the position taken by partisan elites.3 The present paper examines these two points in the context of a national survey experiment which varies both ideological domain and the presence and absence of partisan cues in the content of preference formation over public policy. We examine the association of 2 We do not assume that this form of delegation is consciously based on such dispositions; simply that party imagery is differentially appealing to citizens across needs for certainty and security. 3 If this possibility seems practically irrelevant, consider the passage of the Medicare Modernization Act in 2003. This bill was perhaps the most significant piece of social welfare legislation passed in the U.S. since the 1960s. It was, however, championed by a Republican president, and passed through a Republican Congress, with votes falling largely along party lines. Moreover, within the mass public, support and opposition mirrored the partisan divide at the elite level. For a more recent example, consider that the health care reform bill passed by Democrats was similar in content to alternatives proposed by Republicans in the 1990s during the Clinton administration. 6 psychological needs for certainty and security across these various combinations of characteristics, and find support for our general theoretical position. For relatively easy issues (i.e. social issues and policies related to terrorism) we find unconditional effects of needs on conservatism. For relatively hard issues (i.e. economic issues), by contrast, we find that the presence or absence of party cues strongly moderates the association between needs and conservatism. We additionally consider the broader implications of this dynamic for American politics, suggesting that it implies increasing economic conservatism, on average, among low socioeconomic status citizens as they become increasingly politically engaged. THEORY AND HYPOTHESES What drives the variation in the influence of psychological dispositions across ideological domains? Why does there appear to be a moderating effect of political engagement on their influence (in the economic domain in particular)? We argue that the key to understanding such variation lies in the distinction between “easy” and “hard” issues (Carmines and Stimson 1980). Easy issues possess symbolic referents which are available to all citizens largely independent of their political engagement. Gay marriage, for example, is a prototypical easy issue in the sense that citizens can largely derive their preferences on same-sex legislation regardless of exposure to elite discourse. The symbolic considerations at the heart of the debate (e.g. religion; attitudes toward sex) are accessible to most everyone. This also suggests a straightforward, or relatively unconditional, relationship of citizens’ psychological dispositions to such issues. Recent theorizing regarding the influence of psychological dispositions on ideology posits that traits related to needs for security and certainty drive conservatism on the basis of their differential “fit” with an ideology emphasizing institutional and value stability (e.g. Gerber et al. 2010; Jost et al. 2003; Mondak 2010). To the extent that symbolic referents related to such stability are 7 available and accessible without attention to elite discourse, as should be the case for easy issues generally, associations between needs for certainty and security and preferences should be visible for most citizens. Hard issues, by contrast, are technical and non-symbolic by default, and thus the symbolic meaning of the issues must be constructed in the context of elite political competition. Put simply, in the absence of exposure to elite discourse, there is little reason to expect citizens to naturally connect complex issues to symbolic ideological divisions and abstract values (Converse 1964; Pollock, Lilie and Vittes 1993; Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock, 1991), and thus little reason to expect an unconditional effect of dispositions on preferences (Federico et al. 2011; Jost, Federico and Napier 2009). Instead, when issues are complex, citizens should rely more heavily on elites to form their preferences. More specifically, they should turn to trusted elites for information and guidance regarding the “correct” position to adopt on a given issue (Lupia and McCubbins 1998). Over time, intra-individually, such delegation processes may drive the further development of more abstract values and ideologies related to the issue domain through the reception of elite issue frames and justificatory rhetoric (e.g. Goren 2005; Goren, Federico and Kittilson 2009; Sniderman et al. 1991). Given that the structure of American political conflict largely revolves around the two major parties, such elite delegation should most often manifest as partisan delegation (Cohen 2003; Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen 2012; Rahn 1993; Sniderman 2000; Sniderman 2012; Sniderman and Bullock 2004; Tomz and Sniderman 2005). As such, whatever considerations determine partisan information seeking will also indirectly constrain preferences formed on the basis of such selectivity. In contemporary American politics, dispositions related to basic needs for certainty and security appear to be a key factor determining partisan trust and sorting as a 8 result of the rise of cultural and security-based conflict, and the readily accessible symbolic imagery of such concerns in media treatments of party competition (Hetherington and Weiler 2009). This suggests that such dispositions will indirectly constrain preferences over difficult issues in an implicit two-step process of partisan delegation and cue-taking. In sum, we suggest at least two pathways by which dispositions influence political preferences: an unconditional path for easy issues, and an elite-delegation path for hard issues. We posit that social or cultural issues, generally speaking, are easy issues. They are relatively non-technical and have readily available and accessible symbolic referents. Our categorization is highly consistent with the strong influence of dispositions on social preferences found in previous studies. In contrast, we argue that economic issues are typically hard issues in that they are technical and not symbolic by default. The symbolic content of such issues is typically constructed for citizens by elites (e.g. Shapiro and Jacobs 2010), and thus partisan cues should have a greater effect on citizen preferences in the economic domain relative to the social domain. This categorization is consistent with the weaker associations between dispositions and economic preferences found in previous studies. Moreover, research supports the contention that citizens are more reliant on elite cues in the economic domain. Goren (2005) finds that the influence of partisanship on moral traditionalism is weaker than its influence on egalitarianism and preferences for limited government. Similarly, in an experimental context, Goren, Federico and Kittilsen (2009) find that the presence of partisan cues has a larger effect on citizens’ reported economic values than on their reported cultural values. Cohen (2003) finds very large effects of partisan cues on citizens’ preferences over social welfare provision, such that in the presence of cues which “reverse” party positions (i.e., Democrats as Conservative and Republicans as Liberal), citizens 9 report preferences counter to their stated general ideologies (i.e. Liberal or Conservative identifications). Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen (2012) find that partisanship is more important as a structuring force to policy preferences in the economic domain relative to the social domain. In line with these considerations, we state our first two hypotheses for the present study as the following: (1) For social issues, the influence of needs for certainty and security will be unconditional, i.e., independent of the presence of elite cues (2) For economic issues, the influence of needs for certainty and security will be conditional, i.e., dependent on the presence of elite cues Finally, we consider the expected dynamics for the foreign policy domain. On the one hand, such issues are often considered to be hard issues, and thus citizens are expected to rely strongly on elite cues when forming preferences in this domain (e.g. Berinsky 2007; Zaller 1992). On the other hand, in contemporary American politics, foreign policy issues related to the so-called War on Terror can function as easy issues, as they have readily accessible symbolic referents, namely those related to religion, ethnicity, and the imagery associated with the September 11th, 2001 attacks on the United States. This latter possibility is consistent with the strong relationship of authoritarianism to foreign policy conservatism found in recent work (Hetherington and Suhay 2011; Hetherington and Weiler 2009). We thus test the following third hypothesis in the present study: (3) For foreign policy issues related to terrorism, the influence of needs for certainty and security will be unconditional, i.e., independent of the presence of elite cues 10 We test all three of these hypotheses with a national survey experiment which manipulates the presence and absence of partisan cues in the context of social, economic and foreign policy preferences. In the next section, we describe the experiment in detail and the variables used to operationalize our key constructs. We then turn to the results of the experiment, and address the normative implications of our findings, specifically with respect to social welfare provision in the United States. We conclude with a brief summary and a discussion of our findings and their implications. METHODS Experimental Design To test our three hypotheses, we adapt an experimental design inspired by Goren, Federico and Kittilson (2009) and Cohen (2003) to the present concerns. In this general design, subjects are randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In both conditions, respondents are asked questions regarding their political preferences which contrast two positions placed at opposite ends of a seven-point scale: one representing a stereotypical liberal position, and the other a conservative position. Subjects are asked to place themselves on this scale. In the first, or control condition, subjects are presented with the two issue positions absent of any political labels. In the treatment condition, the liberal and conservative sides of the issue are attributed to the Democratic and Republican Parties, respectively. By comparing the treatment to the control group, inferences regarding the importance of partisan cues to preference formation can be made. Our data come from a national sample of 1200 Americans conducted by the survey firm YouGov Polimetrix from March 4th to March 9th, 2011, weighted to be representative of the American public. In addition to questions regarding demographics, politics, and dispositions, the survey contained an embedded experiment, mentioned above, which we draw on for the present 11 study. Of the 1200 total respondents, 497 were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions, and these individuals constitute the sample for our analyses. The embedded experiment’s stimuli consisted of seven specific policy issues, four economic, two social, and one foreign. The specific items are described further below. Measuring Citizen Dispositions The YouGov survey contained three sets of items intended to measure psychological dispositions related to needs for certainty and security. First, four items operationalized the construct of authoritarianism. Much research on authoritarianism suggests that this trait is strongly related to aversion to uncertainty and threat sensitivity (e.g. see Jost et al. 2003 for a meta-analysis of studies related to this question). Consistent with recent work (Feldman and Stenner 1997; Hetherington and Suhay 2011; Hetherington and Weiler 2009; Stenner 2005), authoritarianism was measured by asking respondents to make four pairwise comparisons of values, and indicate which of each pair they consider more important for a child to possess. The comparisons included, “Independent or Respect for Elders,” “Curiosity or Good Manners,” “Obedience or Self-Reliance,” and “Considerate or Well-Behaved.” Second, five items measured Schwartz’s (1992) value dimension of conservation versus openness to change. Schwartz value theory (Schwartz and Bilsky 1987; Schwartz 1992) posits ten unique value domains, each defined by a set of subordinate individual values, which can be conceptualized as intrinsically desirable ends to which all human beings and groups aspire. Importantly, however, the pursuit of some values impedes the pursuit of others, and these patterns of conflict and harmony amongst desirable ends implies the necessity of trading off some for others. For example, while the simultaneous pursuit of security and conformity is often possible, the simultaneous pursuit of conformity and self-direction is often not possible. These 12 patterns lend structure to citizens’ subjective importance ratings of the various value domains; specifically, they generate a two-dimensional structure (Schwartz 1992). The first of these two dimensions, the one of interest to the present study, is defined by the harmony of the values of security, tradition and conformity on one end, and by self-direction and stimulation on the other. Conceptually, Schwartz (1992) argues that this dimension “arrays values in terms of the extent to which they motivate people to follow their own intellectual and emotional interests in unpredictable and uncertain directions versus to preserve the status quo and the certainty it provides in relationships with close others, institutions, and traditions” (p. 43). This dimension is thus conceptually related to basic needs for security and certainty (see Thorisdottir et al. 2007 for an example which uses Schwartz Value Theory in a similar fashion). This dimension was operationalized with five items, each of which placed two statements at opposite ends of a 10-point scale, and asked respondents to place themselves on that scale according to their relative agreement with each statement. For example, one item contrasted the statement, “To have a good life one must be willing to pursue adventures and take risks,” with, “A safe and secure environment is the best foundation for a good life.” The exact wording for all items is contained in the Appendix. Finally, we utilized five items to measure the construct need for nonspecific cognitive closure (Kruglanski 1989; Kruglanski and Webster 1996; Kruglanski, Webster and Klem 1993). Kruglanski and Webster (1996) define this need as a “desire for a firm answer to a question and an aversion to ambiguity.” Thus, individuals high in the need for closure tend to be dispositionally averse to epistemic uncertainty, and tend toward black and white, or “rigid,” cognitive styles. The five items operationalizing the need for closure in the present study were constructed identically to those for conservation versus openness to change above, using distinct 13 sets of paired statements for each item. For example, the first item contrasted the statement, “I like to have friends who are unpredictable,” with, “I don’t like to be with people who are capable of unexpected actions.” The specific items in this scale appear in the Appendix. On the basis of our review of the literature, we expected that these three dispositional dimensions would be well represented as indicators of a superordinate dimension defined broadly in terms of citizens’ differential needs for epistemic certainty and existential security. To examine this possibility, we estimated a covariance structure model which defined three latent trait dimensions, one for each of the three sets of items described above. Each trait dimension then served as an indicator of a single, superordinate latent factor. The advantage of this specification is that it models the measurement error in the observed indicators, allows each trait to be empirically distinct, and yet still instantiates their common ancestry in a more general latent construct. To the extent that these three traits are indeed indicators of a more superordinate dimension, we should find strong loadings of each on this higher-order factor. On the technical side, we specified logit link functions for the four indicators of authoritarianism, and normal link functions for the other ten indicators. To account for the likely possibility that there are individual differences in the use of the specific instrument for these latter ten (e.g. differences in initial anchoring), we additionally modeled these as a function of a latent “measurement” factor. This is equivalent to a regression of each of the ten items on a latent factor, where the coefficients relating the factor to each indicator are constrained to be equal, and the factor itself is constrained to be uncorrelated with the other latent factors in the model. In other words, the measurement factor allows for the possibility that, independent of the content of the individual items, responses are related due to the idiosyncratic way in which each respondent utilizes the common instrument. All latent factors were identified by fixing their 14 variances to one. The model was estimated via weighted least squares in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2007). To improve the efficiency of our estimates, we utilized the entire 1200 person sample. While the estimates for the model are provided in Appendix C, we highlight the key result here. We find that each of the three latent personality indicators is strongly determined by the hypothesized superordinate dimension. The standardized factor loadings for authoritarianism, conservation versus openness to change, and the need for nonspecific closure on this latent dimension are, respectively, .81, .80, and .54. All three are thus above typical standards for a good indicator, and the loadings for authoritarianism and conservation are very large. Substantively, one can interpret these loadings as the expected change (in standard deviations) of each latent indicator for a one standard deviation change in the superordinate trait dimension. On the basis of these results, we concluded support for our reading of the recent literature, and thus generated factor scores (on the superordinate trait dimension) for each respondent. We utilize these scores as our key independent variable in all analyses to follow. This variable has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, but was recoded to range from zero to one such that higher values indicate greater needs for security and certainty. Dependent Variables4 Our three dependent variables represent respondent preferences over social, foreign and economic policy issues, respectively. The YouGov survey contained two items operationalizing preferences in the social domain, namely, abortion and gay marriage. These two items were highly correlated (r=.50), and were thus averaged to form a single scale with higher values indicating greater social conservatism. Foreign policy preferences were operationalized with a 4 Recall that the individual items differ across the two experimental conditions with respect to the presence or absence of party attributions. 15 single item asking whether the government should be allowed to hold suspected terrorists indefinitely without charging them with a crime. This measure thus taps respondents’ preferences regarding expanded government power to fight terrorism. The item was coded such that higher values indicate greater support for holding terrorists indefinitely, and thus greater foreign policy conservatism in the realm of terrorism. Finally, four items measured economic conservatism, including preferences regarding government provision of health insurance, unemployment insurance, social security, and the desirability of increased regulation of the financial industry. These items formed a highly reliable scale (α=.79) which was coded such that higher values indicate greater economic conservatism. The exact wordings for all items are contained in the Appendix. Further, all three dependent variables were recoded to range from zero to one prior to analysis. Control Variables We control for several additional variables which are likely or arguably exogenous to the key personality dimension of interest, but may be related to both personality and political ideology. These include age, gender (1=male), race (1=black), education (nominally operationalized as six separate categories to allow for non-linearity), income, employment status (1=unemployed), and religiosity. For the religiosity variable, we constructed a scale using three items: the importance of religion to the individual, their frequency of religious service attendance, and their frequency of prayer (α=.87). All controls were recoded to range from zero to one prior to analysis. Analysis We tested our hypotheses with three OLS regressions with robust standard errors. Each model regressed social, foreign, or economic policy conservatism on needs for security and 16 certainty, a dummy indicator for the party cues treatment condition, the interaction of needs with treatment condition, and all controls described above. With this specification, in the social and foreign policy models, we expected a positive and significant constituent term for needs, but minimal and insignificant interaction terms. This pattern suggests an unconditional relationship of dispositions to preferences in these two domains. Conversely, in the economic preferences model, we expected to find a minimal effect of needs in the control condition, but a strong and significant relationship in the treatment condition, indicating a conditional relationship within this domain, and thus support for the two-step model theorized above. RESULTS Influence of Needs on Policy Conservatism The estimates for these three models are shown in the first three columns of Figure 2a. Our results strongly support theoretical expectations. For social and foreign policy preferences, dispositions related to needs for security and certainty strongly and significantly predict conservatism regardless of the presence or absence of elite cues. In both models the coefficient for needs is substantively large, in the expected positive direction, and statistically significant. Additionally, the interactions of needs with treatment condition are minimal and insignificant, as hypothesized. To better interpret these coefficients, we plot the marginal effects of needs across ideological domains and conditions in Figure 2b. Each dot represents the expected change in domain-specific policy conservatism for a change in needs for certainty and security from its 5th to its 95th percentile. Looking at the first two pairs of dots, one can see that the magnitudes of the coefficients are comparable between the social and foreign domains. Across domains and conditions, the effective influence of needs for security and certainty on conservatism is about 17 .30. In other words, a change in these needs from low to high, all else equal, is associated with an increase in social and foreign policy conservatism of about 30% of their respective scales. In contrast, for economic preferences, the coefficient for needs in the control condition, although attaining statistical significance, is about one-third the size of the other two models. From Figure 1b we see that the association of these dispositions with economic conservatism in the absence of elite cues is only .09, or 9% of the scale of the dependent variable. In the presence of partisan cues, however, this association increases substantially. The interaction of needs with treatment condition is substantively large, and statistically significant with a onetailed test.5 In the party cues treatment condition, a change from the 5th to the 95th percentile of needs for certainty and security entails an expected increase in economic conservatism of 21 percentage points, or more than twice the size of the control condition, and approaches the magnitudes for social and foreign preferences. Discovery of such a large effect is striking given that prior research has failed to consistently find effects of related variables in the economic domain. Needs for certainty and security show strong associations with preferences in all three domains, but conditionally so in the economic domain. The importance of partisan cues to the translation of dispositions into economic preferences suggests the possibility that the influence of dispositions will be larger for White Americans, particularly in relation to Black Americans, who tend to identify with the Democratic Party at high rates. As such, Black Americans, regardless of dispositional orientations, are unlikely to accept Republican cues. Indeed, in our sample, less than 6% of Black Americans identify with the Republican Party. To examine this possibility, we re-estimated the economic 5 Given our directional hypothesis, we utilize a one-tailed test for significance. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are reported in Figure 1a for the reader’s convenience. 18 preferences model including only White Americans.67 These estimates are shown in the last column of Figure 1a, and in the last pair of dots in Figure 1b. Once again, our conditional hypothesis receives strong support. In addition, the size of the interaction term is larger than for the full sample model. Looking at Figure 1b, a change from the 5th to the 95th percentile of needs in the control condition entails an expected increase in economic conservatism of about 10 percentage points. In the treatment condition, by contrast, this change entails a 26 percentage point increase in conservatism. There is thus some suggestion that these dynamics may be stronger for White Americans, which would be consistent with other recent work (Gerber et al. 2010), but further research is clearly needed to explore racial and ethnic heterogeneity in the translation of dispositional factors into political preferences. Implications for Social Welfare Provision Having demonstrated the importance of elite cues for the translation of citizens’ psychological dispositions into economic preferences, we turn now to the question of why this dynamic matters for political outcomes in the United States. While the task of uncovering the various influences on political preferences in the mass public may be worthwhile in and of itself, we believe that the dynamics observed above have broader implications, more specifically with respect to the provision of social welfare. On the basis of classical models of economic preferences, we expect citizens of low socioeconomic status to prefer the provision of social welfare and government redistribution to a greater extent than their fellow citizens of high 6 Ideally we would estimate separate models for all racial and ethnic groups in our sample, but the sample sizes for these latter groups would be too small to generate the power needed for a proper test. 7 We also estimated models for social and foreign preferences using this Whites-only subsample to see if this influenced the moderating impact of party cues for these domains. No evidence was found for this additional possibility in the form of interactions with treatment condition, and the substantive results remained nearly identical. The constituent term on needs in the foreign policy model was slightly larger, however. 19 socioeconomic status (Meltzer and Richard 1981). Importantly, however, socioeconomic status is negatively associated with needs for security and certainty, but these needs are positively associated with economic conservatism in the context of exposure to elite-level politics. The interaction of these two insights suggests a perhaps surprising conclusion: as citizens of low socioeconomic status become more involved and engaged with elite-level politics they are expected to become increasingly economically conservative on average – exactly the opposite of what would be expected on the basis of classical rational choice models. As low SES citizens traditionally represent the primary base of support for the provision of social welfare, and given the strong positive skew of the income distribution in the U.S., this dynamic has the capacity to reduce the overall extent of the welfare state in a political environment where the symbolic aspects of party conflict (i.e. cultural concerns) resonate with psychological needs for security and certainty. We examine this dynamic empirically through the specification of a structural equation model linking socioeconomic status to economic preferences both directly and indirectly through needs for security and certainty. In other words, we simultaneously estimated two equations: one identical to those examined above, and a second regressing needs for security and certainty on all demographic and control variables. Given the results above, and the focus of recent “culture war” arguments on blue-collar White America (e.g. Bartels 2006; Frank 2004), we restrict our sample here to White Americans. To account for the moderating role of partisan cues on the influence of needs for certainty and security, we estimated a multiple groups model which allows the effect of needs, and thus the indirect effects of all other variables on economic preferences, to vary across experimental conditions. The model was estimated via maximum likelihood in MPLUS (Muthén and Muthén 2007). 20 The key results of this estimation are shown in Figure 2. Panel A of this figure displays all direct effects of independent variables on needs for certainty and security. As the estimates for the regression of economic preferences on all variables are largely identical to that of the ordinary least squares model above, we do not consider these further here. Examining Panel A, we confirm the relationship of socioeconomic status to needs for security and certainty. Looking at the pattern of coefficients for the education dummies (where “less than a high school degree” is the excluded category), it is clear that there is a strong, yet non-linear relationship between the acquisition of human capital and these basic needs. More specifically, there is an abrupt division between those with a high school degree or less, and those with more than a high school degree, with the latter significantly lower in these needs. Interestingly, however, there appears to be little additional influence of education after the high school degree level, with the possible exception of post-graduate degrees. The relationship of needs to education confirms expectations derived from previous literature. In addition, after controlling for education there is no additional association of needs with income. On the basis of this pattern, and to get a better sense of the substantive meaning of these results, we re-estimated the model treating education as a dummy variable taking a value of one for those with more than a high school degree, and a value of zero for those with a high school degree or less. We then generated predicted values of economic conservatism, across experimental conditions, for each of the two levels of education. These estimates, with their associated 95% confidence bounds, are graphed in Figure 2b. The first two dots show estimated levels of economic conservatism for low education citizens across the two experimental conditions, while the second two dots show the same for high education citizens. This configuration reveals a striking confirmation of the counter-intuitive nature of economic 21 preference formation for low SES citizens, as predicted by the theory above. Specifically, in the presence of elite cues, low education respondents are expected to be more conservative economically than their counterparts in the control condition, and more conservative than high education respondents in either condition.8 The effect of the treatment is not insubstantial. Moving from the control to the treatment group, respondents with a high school degree or less are expected to be about seven percentage points more conservative on average (p<.05). It is also important to note that this increase in conservatism for low education respondents is due solely to the presence of party cues in this one instance. In the real world of day-to-day American politics, we should expect consistent exposure to such cues for politically engaged citizens, and thus more pronounced effects. CONCLUSIONS The present paper makes two theoretical contributions to the literature on the psychological foundations of political ideology. First, we have argued that ideological domains differ with respect to the importance of exposure to elite discourse as a moderator of the translation of psychological dispositions into liberalism and conservatism. More specifically, we suggest that “easy” issues require little political attentiveness, while the translation of dispositions into preferences for “hard” issues requires political attention. While issues may vary on a finer-grained basis, we have argued that, on average, social issues are easy issues, and economic issues are hard issues. This categorization, while imperfect, maps well onto the asymmetry in empirical results found in recent work between these domains, and is both facevalid and intuitive. Empirically, we demonstrate that exposure to elite cues strongly moderates the association of dispositions to preferences in the economic but not the social domain of public 8 The lack of change across conditions for high education respondents is a result of two countervailing effects: education has a positive direct effect on economic conservatism, but a negative indirect effect through needs for certainty and security. 22 policy. Moreover, we demonstrate that foreign policy issues related to terrorism may function more like easy issues than hard issues, even if foreign policy preference formation, in general, may be strongly dependent on elite signals (Berinsky 2007; Zaller 1992). Second, we have argued that elite-delegation and cue-taking is one important mechanism which can account for recent theorizing and empirical results which suggest a moderating role for political engagement in the translation of dispositions into preferences and ideology (Jost, Federico and Napier 2009; Federico et al. 2011). Such work seems to suggest that the key mechanism is exposure to ideological ideas, but we argue that this is not necessary. Rather, citizens seek information at the elite level in a partisan fashion, and such partisan informationseeking is itself derivative of more basic matches between psychological dispositions and symbolic party imagery. Consistent with other work in political psychology (e.g. Alford, Funk and Hibbing 2005; Cohen 2003; Lavine, Johnston and Steenbergen 2012), the ideological content of a policy concerning a hard issue may matter less than who supports and opposes that policy. This is a critically important point for the literature, because it suggests that needs for certainty and security and their related traits, or any other politically-relevant dispositions for that matter, have the potential to be associated with a wide range of political preferences conditional on the nature of elite conflict at any given time. This is not to say that ideas do not matter at all, they surely do, but simply that they may be less important for preference formation on a policy to policy basis than previous research has recognized. Future work should consider the interaction of cues and ideas to better disentangle their relative importance and interactive effects. Additionally, the present study does not consider the potential for “reversals” of the kind observed by Cohen (2003) as a function of counter-stereotypical cues. This represents a 23 limitation of the present study’s empirics, however, the logic of the theory, the demonstration of the importance of partisan cue-taking in the present study, and related research on partisan cuetaking in political science all suggest that reversals are likely for hard issues with counterstereotypical cues. Finally, the present study contributes to perennial debates over the importance of the “culture war” to American politics. In the last section of the paper, we demonstrate that our theoretical model implies, somewhat counter-intuitively, that low SES White citizens will become increasingly conservative as they increase their political engagement. This is a straightforward implication of the negative association of needs for certainty and security with socioeconomic status, and the positive association of such needs with economic conservatism in the presence of elite cues and discourse. This is, in essence, similar to the dynamic highlighted by popular accounts of the “culture war” (e.g. Frank 2004), namely, that low SES White citizens, as a function of the rise of cultural politics, have become increasingly Republican and conservative in the last few decades. The implication of this is a decline in social welfare provision as the base of support for such policies weakens over time. A critical distinction, however, is that the debate over the culture war has focused on whether such issues have displaced the economic domain or not. As political scientists have amply demonstrated, this is simply not the case; economic issues remain the dominant concern of citizens, and the most important predictor of their voting behavior and partisanship (Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder 2006; Bartels 2006; 2008; Gelman 2008; Smith 2009). The present paper, however, suggests a more subtle mechanism by which social welfare provision may be affected by the culture war, broadly defined. Specifically, the rise of cultural and security-based partisan conflict has increased the importance of sorting on the basis of 24 dispositions related to needs for security and certainty. This, in turn, and as a result of the association between such needs and socioeconomic status, has led to the conversion of many politically engaged, low SES Whites to economic conservatism, shifting the overall distribution of preferences over social welfare to the conservative end of the spectrum. In other words, even though the economic domain has not been displaced, economic preferences are at least partially endogenous to processes which are critically dependent on cultural conflict at the elite level. 25 REFERENCES Alford, John R., Carolyn L. Funk, and John R. Hibbing. 2005. “Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted?” American Political Science Review 99(02): 153–167. Amodio, David M., John T. Jost, Sarah L. Master, and Cindy M. Yee. 2007. “Neurocognitive Correlates of Liberalism and Conservatism.” Nature Neuroscience 10: 1246-1247. Ansolabehere, Stephen, Jonathan Rodden, and James M. Snyder. 2006. “Purple America.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(2): 97–118. Bartels, Larry M. 2006. “What’s the Matter with What’s the Matter with Kansas?” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 1(2): 201–226. Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Berinsky, Adam J. 2007. “Assuming the Costs of War: Events, Elites, and American Public Support for Military Conflict.” Journal of Politics 69(4): 975–997. Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1980. “The Two Faces of Issue Voting.” The American Political Science Review 74(1): 78–91. Carney, Dana R., John T. Jost, Samuel D. Gosling, and Jeff Potter. 2008. “The Secret Lives of Liberals and Conservatives: Personality Profiles, Interaction Styles, and the Things They Leave Behind.” Political Psychology 29 (6): 807-840. Chirumbolo, Antonio, Alessandra Areni, and Gilda Sensales. “Need for Cognitive Closure and Politics: Voting, Political Attitudes and Attributional Style.” International Journal of Psychology 39 (4): 245-253. Cohen, Geoffrey L. 2003. “Party Over Policy: The Dominating Impact of Group Influence on Political Beliefs.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85(5): 808–822. Converse, Philip. 1964. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” In Ideology and Discontent, ed. David Apter. New York: Free Press, pp. 206-261. Federico, Christopher M., Emily L. Fisher, and Grace Deason. 2011. “Expertise and the Ideological Consequences of the Authoritarian Predisposition.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75(4): 686–708. Federico, Christopher M., and Paul Goren. 2009. “Motivated Social Cognition and Ideology: Is Attention to Elite Discourse a Prerequisite for Epistemically Motivated Political Affinities?” In Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification, eds. John T. Jost, Aaron C. Kay, and Hulda Thorisdottir. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 26 Feldman, Stanley, and Christopher D. Johnston. 2009. “Understanding Political Ideology: The Necessity of a Multidimensional Conceptualization.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Feldman, Stanley, and Karen Stenner. 1997. “Perceived Threat and Authoritarianism.” Political Psychology 18(4): 741–770. Frank, Thomas. 2004. What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Gelman, Andrew. 2008. Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State: Why Americans Vote the Way They Do. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Gerber, Alan S., Gregory A. Huber, David Doherty, Conor M. Dowling, and Shang E. Ha. 2010. “Personality and Political Attitudes: Relationships across Issue Domains and Political Contexts.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 111-133. Golec, Agnieszka. 2001. “Need for Cognitive Closure and Political Conservatism: Studies on the Nature of the Relationship. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Cuernavaca, Mexico. Goren, Paul. 2005. “Party Identification and Core Political Values.” American Journal of Political Science 49(4): 881–896. Goren, Paul, Christopher M. Federico, and Miki Caul Kittilson. 2009. “Source Cues, Partisan Identities, and Political Value Expression.” American Journal of Political Science 53(4): 805–820. Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. Weiler. 2009. Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hetherington, Marc, and Elizabeth Suhay. 2011. “Authoritarianism, Threat, and Americans’ Support for the War on Terror.” American Journal of Political Science 55(3): 546–560. Higgins, E. Tory. 1999. “Persons and Situations: Unique Explanatory Principles or Variability in General Principles?” In The Coherence of Personality: Social-Cognitive Bases of Consistency, Variability, and Organization, Daniel Cervone and Yuichi Shoda (Eds.). New York: The Guilford Press. Johnston, Christopher D. 2011. The Motivated Formation of Economic Preferences. State University of New York at Stony Brook. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/897963495?accountid=10598 Jost, John T., Christopher M. Federico, and Jaime L. Napier. 2009. “Political Ideology: Its Structure, Functions, and Elective Affinities.” Annual Review of Psychology 60(1): 307– 337. 27 Jost, John T., Jack Glaser, Arie W. Kruglanski, and Frank J. Sulloway. 2003. “Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition.” Psychological Bulletin 129 (3): 339-375. Kruglanski, Arie W. 1989. Lay Epistemics and Human Knowledge: Cognitive and Motivational Bases. New York: Plenum Press. Kruglanski, Arie W., and Donna M. Webster. 1996. “Motivated Closing of the Mind: ‘Seizing’ and ‘Freezing’.” Psychological Review 103(2): 263–283. Kruglanski, Arie W., Donna M. Webster, and Adena Klem. 1993. “Motivated Resistance and Openness to Persuasion in the Presence or Absence of Prior Information.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(5): 861–876. Lau, Richard R., and David P. Redlawsk. 2006. How Voters Decide: Information Processing in Election Campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press. Lavine, Howard, Christopher D. Johnston, and Marco Steenbergen. 2012. The Ambivalent Partisan: How Critical Loyalty Promotes Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lupia, Arthur, and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1998. The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What They Need to Know? New York: Cambridge University Press. Meltzer, Allan H, and Scott F. Richard. 1981. “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.” The Journal of Political Economy 89(5): 914–27. Mondak, Jeffery J. 2010. Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press. Muthén, L.K. and Muthén, B.O. (1998-2007). Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén Oxley, Douglas R., Kevin B. Smith, John R. Alford, Matthew V. Hibbing, and Jennifer L. Miller, Mario Scalora, Peter K. Hatemi, and John R. Hibbing. 2008. “Political Attitudes Vary with Physiological Traits.” Science 321: 1667-1670. Pollock, Philip H. III, Stuart A. Lilie, and M. Elliot Vittes. 1993. “Hard Issues, Core Values and Vertical Constraint: The Case of Nuclear Power.” British Journal of Political Science 23(01): 29–50. Rahn, Wendy M. 1993. “The Role of Partisan Stereotypes in Information Processing about Political Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37 (2): 472-496. Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. “Universals in the Content and Structure of Values.” In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 25, pp.1-65). New York: Academic Press. Schwartz, Shalom H., and Wolfgang Bilsky. 1987. “Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53(3): 550–562. 28 Settle, Jaime E., Christopher T. Dawes, Nicholas A. Christakis, and James H. Fowler. 2010. “Friendships Moderate an Association between a Dopamine Gene Variant and Political Ideology.” Journal of Politics 72 (4): 1189-1198. Shapiro, Robert Y., and Lawrence Jacobs. 2010. “Simulating Representation: Elite Mobilization and Political Power in Healthcare Reform.” The Forum 8(1): 1-15. Smith, Mark A. 2009. The Right Talk: How Conservatives Transformed the Great Society into the Economic Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sniderman, Paul M. 2000. “Taking Sides: A Fixed Choice Theory of Political Reasoning.” In Elements of Reason: Cognition, Choice, and the Bounds of Rationality, eds. Arthur Lupia, Matthew D. McCubbins, and Samuel L. Popkin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sniderman, Paul M., and Edward H. Stiglitz. 2012. The Reputational Premium: A Theory of Party Identification and Policy Reasoning. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sniderman, Paul M., and John Bullock. 2004. “A Consistency Theory of Public Opinion and Political Choice: The Hypothesis of Menu Dependence.” In Studies in Public Opinion: Nonattitudes, Measurement Error, and Change, eds. Willem E. Saris and Paul M. Sniderman. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sniderman, Paul M., Richard A. Brody, and Phillip E. Tetlock. 1991. Reasoning and Choice: Explorations in Political Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stenner, Karen. 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press. Thorisdottir, Hulda, and John T. Jost. 2011. “Motivated Closed-Mindedness Mediates the Effect of Threat on Political Conservatism.” Political Psychology 32 (5):785-811. Thorisdottir, Hulda, John T. Jost, Ido Liviatan, and Patrick E. Shrout. 2007. “Psychological Needs and Values Underlying Left-Right Political Orientation: Cross-National Evidence From Eastern and Western Europe.” Public Opinion Quarterly 71 (2): 175-203. Tomz, M., and P.M. Sniderman. 2005. “Brand Names and the Organization of Mass Belief Systems.” Unpublished Manuscript. Van Hiel, Alain, and Ivan Mervielde. 2004. “Openness to Experience and Boundaries in the Mind: Relationships with Cultural and Economic Conservative Beliefs.” Journal of Personality 72 (4): 659-686. Van Hiel, Alain, Mario Pandelaere, and Bart Duriez. 2004. “The Impact of Need for Closure on Conservative Beliefs and Racism: Differential Mediation by Authoritarian Submission and Authoritarian Dominance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30(7): 824– 837. Zaller, John. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press. 29 APPENDIX A. SCHWARTZ VALUES AND NEED FOR CLOSURE ITEMS Schwartz Values “How would you place your views on this scale? 1 means you agree completely with the statement on the left; 10 means you agree completely with the statement on the right; and if your views fall somewhere in between, you can choose any number in between.” [Left] To have a good life one must be willing to pursue adventures and take risks [Right] A safe and secure environment is the best foundation for a good life [Left] It is best for everyone if people try to fit in instead of acting in unusual ways [Right] People should be encouraged to express themselves in unique and possibly unusual ways [Left] People should not try to understand how society works but just accept the way it is [Right] People should constantly try to question why things are the way they are [Left] It is most important to give people the freedom they need to express themselves [Right] Our society will break down if we allow people to do or say anything they want [Left] We should admire people who go their own way without worrying what others think [Right] People need to learn to fit in and get along with others Need for Nonspecific Cognitive Closure “How would you place your views on this scale? 1 means you agree completely with the statement on the left; 10 means you agree completely with the statement on the right; and if your views fall somewhere in between, you can choose any number in between.” [Left] I don’t like going into a situation without knowing what I can expect from it. [Right] I enjoy the uncertainty of going into a new situation without knowing what might happen. [Left] In most social conflicts, I can easily see which side is right and which is wrong [Right] In most social conflicts, I can easily see how both sides could be right [Left] I think it is fun to change my plans at the last moment [Right] I hate to change my plans at the last moment [Left] I like to have friends who are unpredictable [Right] I don’t like to be with people who are capable of unexpected actions [Left] I tend to put off making important decisions until the last possible moment [Right] I usually make important decisions quickly and confidently 30 APPENDIX B. EXPERIMENTAL DEPENDENT VARIABLES (In Party Cues Condition, “Some” and “Others” replaced with party labels) Economic Items 1. Some people believe there should be a government insurance plan which would cover all medical expenses for everyone. Suppose these people are at one end of a scale, at point 1. Others believe that all medical expenses should be paid by individuals through private insurance plans. Suppose these people are at the other end, at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between, at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Government insurance plan (7) Private Insurance plan 2. Some people believe that we should get rid of government provided unemployment insurance altogether. Suppose these people are at one end of the scale at point 1. Others believe that we should greatly increase unemployment insurance. Suppose these people are at the other end of the scale at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Get rid of unemployment insurance altogether (7) Greatly increase unemployment insurance 3. Some people believe that we should greatly increase government regulation of the financial industry. Suppose these people are at one end of the scale at point 1. Others believe that we should get rid of financial regulations altogether. Suppose these people are at the other end of the scale at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Greatly increase financial regulations (7) Get rid of financial regulations altogether 4. Some people believe that we should allow people to invest all of their Social Security benefits in the private markets. Suppose these people are at one end of the scale at point 1. Others believe that all Social Security benefits should be handled by the government. Suppose these people are at the other end of the scale at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Allow all benefits to be invested in private markets (7) All benefits handled by government 31 Social Items 1. Some people strongly oppose legalizing gay marriage. Suppose these people are at one end of a scale, at point 1. Others strongly support legalizing gay marriage. Suppose these people are at the other end, at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between, at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Strongly oppose legalizing gay marriage (7) Strongly support legalizing gay marriage 2. Some people believe that women should always be able to get an abortion for any reason. Suppose these people are at one end of a scale, at point 1. Others believe that abortions should always be illegal no matter what the reason. Suppose these people are at the other end, at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between, at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Always able to get an abortion (7) Abortion always illegal Foreign Policy (Terrorism) 1. Some people believe that the government should be allowed to hold suspected terrorists indefinitely without charging them with a crime. Suppose these people are at one end of a scale, at point 1. Others believe that suspected terrorists should be afforded the same rights as regular suspected criminals. Suppose these people are at the other end, at point 7. And, of course, some other people have opinions somewhere in between, at points 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. Where would you place YOURSELF on this scale? (1) Hold terrorist suspects indefinitely (7) Give terrorist suspects same rights 32 APPENDIX C. COVARIANCE STRUCTURE MODEL ESTIMATES FOR DISPOSITIONS Item Std. Loading 1 2 3 4 5 .39 -.56 -.43 .48 .58 1 2 3 4 5 -.57 -.23 .55 .60 .11 1 2 3 4 .72 .73 .70 .51 CO NC AT .80 .54 .81 Conservation v. Openness to Change Need for Closure Authoritarianism Superordinate Dimension TLI RMSEA χ2/df N .85 .07 6.46 1200 33 Figure 1a. OLS Regression Estimates and 95% Confidence Bounds Social Terrorism Econ - All Rs Econ - Whites Needs for C&S Needs x Cues R2=.37, N=493 R2=.15, N=492 R2=.14, N=494 R2=.20, N=360 Party Cues Age Male Black HS Degree Some College 2-Year Deg. BA Deg. Post-Grad Income Unemployed Religiosity -.2 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 -.2 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 -.2 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 -.2 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 Notes: All variables are coded on a 0-1 scale Figure 1b. Marginal Effects of Needs on Policy Conservatism Social Terrorism Econ - All Rs Econ - Whites 0 .1 .2 Control .3 .4 .5 Party Cues Notes: Effects are for changes in needs from 5% to 95% 34 Figure 2a. Predictors of Needs for Certainty and Security 7-Cat Education 2-Cat Education Age Male HS Degree/>HS Some College 2-Year Degree BA Degree Post-Grad Income Unemployed Religiosity -1 -.5 0 .5 -1 -.5 0 .5 Notes: ML estimates from structural equation model. DV: mean=0, sd=1 8 Figure 2b. Predicted Values of Economic Conservatism HS Degree or Less More Than HS Degree .45 .5 .55 Control .6 .65 .7 Party Cues Notes: Based on SEM estimates. All controls held at central tendencies. DV ranges 0-1. 35