The Policy *Landscape - COT Annual Conference

advertisement

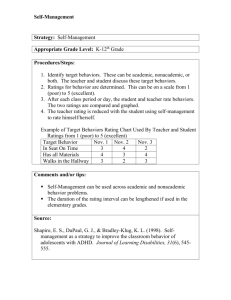

Rehabilitation in the Workplace - Supporting self-management Stephen Bevan The Work Foundation Lancaster University, UK © The Work Foundation, 2015 Health & Work Agenda • Economic story about workforce health and lost productive capacity • The ‘burden of disease’ impact on quality of life & independent living • Raising rehabilitation up the policy ‘priority list’ as the workforce ages • Embedding ‘Work’ as a clinical outcome and a treatment goal (clinical guidelines; care plans) • Focusing on Job Retention, RTW & ‘Good Jobs’ • Taking a biopsychosocial approach – (comorbidity) • Incentivising employers to invest in prevention & early intervention • Empowering people living with MSK to disclose & selfmanage in both clinical & workplace settings Days Lost to Strike Action (UK) The ‘Winter of Discontent’ 1978-79 29 Million Days Lost to MSK (UK) ONS Data from 2013 31 Million ©The Work Foundation MSK and Disability • Ranking of major causes of death and disability (% DALYs) • Cardiovascular and circulatory diseases 11.8% • All neoplasms 7.6% • Mental and behavioural disorders 7.4% • Musculoskeletal disorders 6.8% • Yet MSK not considered a priority noncommunicable disease – Low mortality but High morbidity LTCs in the UK Working Age Population - 2030 Cancer 800k Diabetes 1.3m Mental Health 7m Mental Health CHD MSDs 7m Stroke COPD Asthma MSDs Cancer Diabetes Comorbidity N=21.6m Asthma 2.6m COPD 1.6m Source: Vaughan-Jones & Barham, 2009 CHD 1m Stroke 367k Global ‘Fit for Work’ Study McGee, Bevan & Quadrello, 2009 Why ‘Self-management’? • Strong clinical emphasis for people with chronic but manageable conditions • Previous TWF study found that individuals with MSDs who played an active role in selfmanaging their condition were less worried about retaining their job • Less emphasis in workplace settings or in vocational rehabilitation • Natural terrain for OT expertise http://www.theworkfoundation.com/Reports/370/Selfmanagement-of-chronic-musculoskeletal-disorders-and-employment Definition “Self-management refers to the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychological consequences and life style changes inherent in living with a chronic condition. Efficacious self-management encompasses ability to monitor one’s condition and to affect the cognitive, behavioural and emotional responses necessary to maintain a satisfactory quality of life. Thus, a dynamic and continuous process of self-regulation is established.” Barlow et al, 2002:178 Benefits • appropriate exercise and diet • mental strategies to cope with pain • knowledge and ability to advocate for changes in medication • strategies to cope with fatigue • ability to set and achieve goals (solutionorientation; internal locus of control*) • maintaining a positive outlook • cultivating discipline and motivation *Chang et al, 2013 Four Stages of Self-management • • • • Seeking effective self-management strategies. Considering costs and benefits. Creating routines and plans of action. Negotiating self-management that fits one’s life. (Audulv et al., 2012:331) Self-Advocacy & Negotiation • Fear about the consequences of disclosure (boss, co- workers, pay, careers, task allocation, training opportunities, redundancy) • Satisfied with ‘any’ job? Skill utilisation & mental health • Self-confidence & self-efficacy • ‘Special treatment’, ‘being a burden’ & ‘standing out’ • Using workplace adjustments to ‘co-produce’ mutually advantageous solutions – big role for OTs? • Worker-led but supported adjustments are best • ‘Best adjustment is a great line manager’ Lorig’s Stanford Model (Arthritis) • Techniques to deal with problems such as pain, fatigue, frustration and isolation. • Appropriate exercise for maintaining and improving strength, flexibility, and endurance. • Appropriate use of medications. • Communicating effectively with family, friends, and health professionals. • Healthy eating. • Making informed treatment decisions. • Disease related problem solving. • Getting a good night's sleep. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/asmp.html Ory et al, 2013 Participant Testimony Adjusting the ‘Rhythm’ of Work “As far as helping me, perhaps being a bit more lenient with my hours, that would have really helped. Because I kept killing myself to get up early so that I could be in work for half eight or nine o'clock. Potentially a flexi time of sorts would really help someone with rheumatoid arthritis. Because classically the symptoms are at their worst, in the mornings. First thing in the morning you can.. it’s like a diesel engine, it takes a while to warm up. I am not a petrol engine, I am diesel.” Disclosure & Openness “I used to wear a wrist splint on the days that I felt particularly bad. Because even if it wasn’t my wrist, I just felt it would be a good way for people to know that everything wasn’t ok, without having to tell people.” Job or Career? “I decided not to go for the head of the area [post] but to take a role that would allow me to put myself and my condition first. It’s frustrating that is where I am stuck at career wise ....there’s no chance of career progression. It can be quite frustrating .........doing the same thing knowing I’m not going to get anywhere.” Self-Employment? “I made the big decision that I just couldn’t do a normal job and work for a normal company. The only way I could stay in work was to work for myself, where I was more in control of things.” Reflections • Over 60% of people with MSK are primary income earner in their household – anxiety about job loss can be serious, but so can disclosure & ‘under-employment’ • We can’t just ‘do’ workplace adjustments ‘to’ people – they have both knowledge about & a stake in a good outcome for them & their boss • Supported self-management, led by the worker, frequently monitored, supported and updated with OT input can improve confidence and support recovery & productivity Is any job a ‘Good Job’? ‘Good Jobs’: A Message From HILDA • Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey • Analysis (Butterworth et al, 2011) of seven waves of data from 7,155 respondents of working age (44,019 observations) from a national household panel survey. • Longitudinal regression models evaluated the concurrent and prospective association between employment circumstances (unemployment and employment in jobs varying in psychosocial job quality) and mental health, assessed by the MHI-5 Psychosocial Job Quality (1) Job demands & complexity 1. My job is more stressful than I ever imagined 7. My job is complex and difficult 8. My job requires learning new skills 9. I use my skills in current job Job control 10. I have freedom to decide how I do work 11. I have a lot of say about what happens 12. I have freedom to decide when I do work Job security Effortreward fairness 4. I have a secure future in my job 5. Company I work for will be in business in 5yrs 6. I worry about the future of my job 3. I get paid fairly for the things I do in my job Source: Butterworth et al, 2011 Psychosocial Job Quality (2) “As hypothesised, we found that those respondents who were unemployed had significantly poorer mental health than those who were employed. However, the mental health of those who were unemployed was comparable or more often superior to those in jobs of the poorest psychosocial quality.” Source: Butterworth et al, 2011 Challenges for OTs • The future is multi-disciplinary • Too modest for your own good? • "hey, the therapist didn't even do anything - I just did it all myself!“ • A voice at national level debate AND in business • ‘Activities of Daily Living’ need to include work – especially ‘Good Work’ Resources Arthritis Care http://www.arthritiscare.org.uk/LivingwithArthritis/Selfmanagement/Waystoself-manage Health Foundation http://www.health.org.uk/news-and-events/press/new-onlineresource-launched-to-support-self-management/ MS Society http://www.mssociety.org.uk/ms-resources/working-yetworried-toolkit www.theworkfoundation.com sbevan@theworkfoundation.com @StephenBevan References & Disclosure Audulv, Å., Asplund, K., and Norbergh, K. G, The integration of chronic illness self-management. Qualitative health research, 22(3), 332-345, 2012. Bevan S https://theconversation.com/any-job-isnt-necessarily-a-good-job-for-people-out-of-work-35217 Butterworth, P., Leach, L. S., Strazdins, L., Olesen, S. C., Rodgers, B. et al. (2011). The psychosocial quality of work determines whether employment has benefits for mental health: results from a longitudinal national household panel survey. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, first published online on March 14, 2011, doi:10.1136/ oem.2010.059030 Chang, N, Chiou, C, Wang, C, Su, M and Lo, S Correlation Study Between Health Locus of Control and Dyspnea Self-Management Strategies in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Journal of Nursing & Healthcare Research, Vol. 9 Issue 1, p42, 2013. Ory, M, Ahn, S, Jiang, L, Smith, Matthew L, Ritter, P, Whitelaw, N and Lorig, K, Successes of a National Study of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: Meeting the Triple Aim of Health Care Reform, Medical Care, 51(11), pp 992-998, 2013. Summers K, Bajorek Z and Bevan S, Self-management of chronic musculoskeletal disorders and employment, London: The Work Foundation, 2014. Disclosure The Work Foundation is a not-for-profit organisation. It receives a grant from Abbvie to fund the Fit for Work initiative in Europe and in other parts of the world. The Work Foundation retains editorial control over all Fit for Work outputs.