MS WORD Document size: 1.00 MB

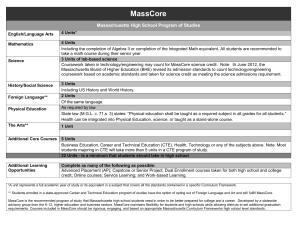

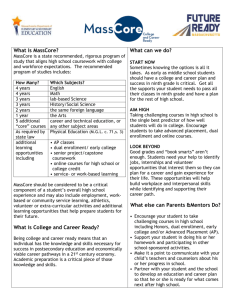

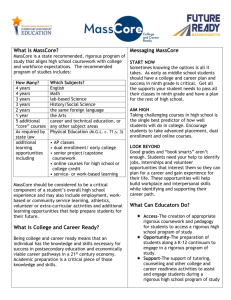

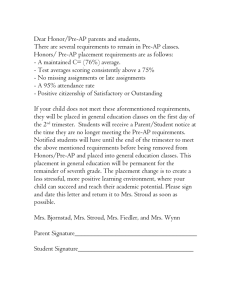

advertisement