Fiduciary Relationships - The University of Sydney

advertisement

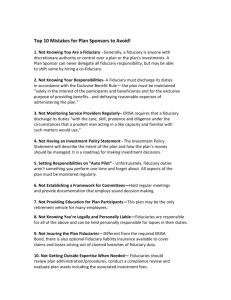

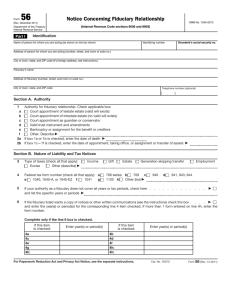

Fiduciary Relationships Professor Cameron Stewart Fiduciary? The word ‘fiduciary’ has its roots in the Latin word fiducia, which means confidence. A fiduciary relationship is thus a relationship of confidence. The person in whom confidence is reposed within that relationship is referred to as the fiduciary. If a fiduciary abuses his or her position to obtain an advantage or benefit at the expense of the confiding party, the latter will be able to seek relief from a court of equity to prevent such advantage accruing to the fiduciary. Equity and fiduciaries Equity intervenes ... not so much to recoup a loss suffered by the plaintiff as to hold the fiduciary to, and vindicate, the high duty owed to the plaintiff ... [T]hose in a fiduciary position who enter into transactions with those to whom they owe fiduciary duties labour under a heavy duty to show the righteousness of the transactions. Maguire v Makaronis (1997) 188 CLR 449 at 465 Undivided Loyalty The essence of fiduciary obligations is that the fiduciary is precluded from acting in any other way than in the interests of the person to whom the duty to so act is owed. In short, the fiduciary obligation is one of ‘undivided loyalty’: Beach Petroleum NL v Kennedy (1999) 48 NSWLR 46–7. Undivided Loyalty The Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) (2009) 70 ACSR 1 at [4552], Owen J said: In my view the state of the law is this. Where a person has undertaken to act in the interests of another and where the nature of that relationship, its surrounding circumstances and the obligations attaching to it so require, it will be held to be fiduciary. But the fact that it is categorised as fiduciary does not mean that all of the obligations arising from it are themselves fiduciary. Unless there are some special circumstances in the relationship, the duties that equity demands from the fiduciary will be limited to what I have described as the core obligations: not to obtain any unauthorised benefit from the relationship and not to be in a position of conflict. They stem from the fundamental obligation of loyalty Strict duties The fact that there was no intent to defraud on the part of the fiduciary is irrelevant: Nocton v Lord Ashburton [1919] AC 492. The liability of the fiduciary does not depend on establishing that the person to whom fiduciary duties are owed suffered loss or injury: Birtchnell v Equity Trustees, Executors and Agency Co Ltd (1929) 42 CLR 384 at 408–9, per Dixon J. A fiduciary’s liability arises even if the person to whom the duty is owed was unlikely or even unable to have made a profit from an opportunity exploited by the fiduciary: Warman International Ltd v Dwyer (1995) 182 CLR 544 at at 558; 128 ALR 201 at 209. Nor will it matter that the beneficiary would have consented to the fiduciary making a profit had the beneficiary been properly informed, if informed consent was never obtained: Murad v Al-Saraj [2005] EWCA Civ 959. Nocton v Lord Ashburton Nocton was a solicitor Lord Asburton was his client Nocton and Baring (Ashburton’s brother) entered into a land development They later agreed to sell the land to Douglas and Holloway but Douglas and Holloway needed a mortgage Nocton convinced Ashburton to lend them the money, after a valuation (even after being warned by Later, as the properties were developed, it became clear that there was insufficient security in the land At trial the judge treated the case as one of fraud and found not evidence of intention The Court of Appeal, found that there was actual fraud which would enable an action in deceit Nocton v Lord Ashburton Viscount Haldane was very critical of the proceedings but said that there was a third way – breach of fiduciary duty That breach did not require that actual fraud be proved in the common law sense of intention Lord Dunedin and Lord Shaw agreed Horizontal duties Fiduciary duties Partner Partner Vertical duties Guardian Fiduciary Ward Duties Negative duties Equity does not require the fiduciaries to act positively in the interests of their beneficiaries: Friend v Brooker (2009) 255 ALR 601 at [84] A fiduciary’s obligation ‘does ... not impose positive legal duties on the fiduciary to act in the interests of the person to whom the duty is owed’: Breen v Williams (1996) 186 CLR 71 at 113; 138 ALR 259 at 289 It is said that such positive duties are better regulated by contract, tort or other equitable doctrines: Pilmer v Duke Group Ltd (in liq) (2001) 207 CLR 165 at 198 Exception? Duty to disclose possible conflicts of interests and seek the informed consent of the beneficiary of the relationship Fitzwood Pty Ltd v Unique Goal Pty Ltd (in liq) (2001) 188 ALR 566, at 576, Finkelstein J refused to describe the obligation to seek informed consent as a positive duty but instead described it as a ‘means by which the fiduciary obtains the release or forgiveness of a negative duty. Exception? The Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) Directors had breached their duties to act in the best interests of their companies and to exercise their powers properly, when they had authorised loans which where in the overall interests of the corporate group, but not in the interests of some of the individual companies within that group Owen J found that the directors’duties to act in the companies’ best interests and to exercise powers properly were fiduciary duties. In so finding Owen J argued that these duties were, in substance, negative or proscriptive duties. How? Fiduciary duties protect economic interests Traditional reluctance New equity? Giller v Procopets [2008] VSCA 236 The existence of a fiduciary relationship Breen v Williams at CLR 92; ALR 273, Dawson and Toohey JJ observed that the law has not formulated ‘any precise or comprehensive definition of the circumstances in which a person is constituted a fiduciary in his or her relations with another’ Presumed fiduciary relationships A number of commercial and professional relationships: Trustee and beneficiary director–company legal practitioner–client agent–principal partner–partner Key features? Loyalty Trust Confidence Vulnerability Undertaking Finn – reasonable expectations Glover – same old problem Fiduciary Relationships outside of the presumed categories Factors include – the undertaking to fulfil a duty in the interests of another, – the scope for one party to unilaterally exercise a power or discretion that may affect the rights or interests of another; and – a dependency on the part of one party which causes that party to rely upon the other. Fiduciary Relationships outside of the presumed categories Economic power/free hand of market Equity’s intervention distorts economic activity? Should equity be reluctant to intervene? United Dominions Corporation Ltd v Brian Pty Ltd Joint venture agreement for the development of land between United Dominions Corporation (UDC), Security Projects Ltd (SPL) and Brian Pty Ltd (Brian). Land owned by SPL Financed by UDC on security raised from SPL Profits made but UDC kept more than its share by using a clause in the mortgage to SPL Brian didn’t know about the clause and received no profit Did UDC owe Brian a fiduciary duty? United Dominions Corporation Ltd v Brian Pty Ltd The High Court found in Brian’s favour. It held that SPL and UDC owed fiduciary duties to Brian and that the collateralisation clause in the mortgage was obtained in breach of such duties. Dawson J at CLR 16; ALR 750–1 said: [I]t is quite clear that a fiduciary relationship may arise during negotiations for a partnership or, for that matter, a joint venture, before any partnership or joint venture agreement has been finally concluded if the parties have acted upon the proposed agreement as they had in this case. Whilst a concluded agreement may establish a relationship of confidence, it is nevertheless the relationship itself which gives rise to fiduciary obligations. That relationship may arise from the circumstances leading to the final agreement as much as from the fact of the final agreement itself. Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corporation Blackman had an exclusive distributorship arrangement for products manufactured by United States Surgical Corporation (USSC) Blackman’s company, Hospital Products Ltd (HPL), was soon after substituted as the distributor. HPL, using USSC products as models, began to manufacture products that were essentially identical to those manufactured by USSC > HPL went into competition with USSC Was HPL a fiduciary? Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corporation By a bare majority the High Court held that there was no fiduciary relation ship between the parties and that USSC’s right to relief rested in a claim for damages for breach of contract. The majority considered that because the relationship between the parties was a commercial one entered into by equal parties at arm’s length with the intention that both parties would gain a profit, it was inappropriate to find a fiduciary relationship between the parties A vexed question…. Why was there a fiduciary relationship in one and not the other? Does Equity have any role in commercial bargaining? Are the economic costs of imposing fiduciary relationships outweighed by advantages? Length of the Chancellor’s Foot? The fiduciary obligation Aberdeen Railway Co v Blaikie Brothers [1854] 1 Macq 461 at 471 [A fiduciary will not be permitted] to enter into engagements in which he has, or can have, a personal interest conflicting, or which possibly may conflict, with the interests of those whom he is bound to protect The fiduciary obligation The duty imposed upon a fiduciary operates in circumstances where there is a conflict between the fiduciary’s ‘duty’ and his or her ‘interest’. Duty The word ‘duty’ in this context does not have a technical meaning. It does not refer to legally imposed obligations. Rather, it refers to the actions undertaken by a fiduciary on behalf of another person. These actions are not confined to those undertaken in the performance of a fiduciary’s mandatory or discretionary functions. These actions also include voluntary acts. Interest The word ‘interest’, in this context, signifies the presence of some personal concern on the part of a fiduciary or of possible significant pecuniary value in a decision to be taken by the fiduciary. Finn (1977) at 204 notes: The pecuniary dimension of the fiduciary’s concern may take the form of an actual, prospective, or possible profit to be made in, or as a result of, the decision he takes or the transaction he effects. Or it may take the form of an actual, prospective, or possible saving, or a diminution of a personal liability Informed consent The duty imposed upon the fiduciary is strict. The only way a fiduciary is able to escape liability for conduct that amounts to a breach of fiduciary duty is if the conduct was undertaken with the fully informed consent of the person to whom the fiduciary obligations are owed. The disclosure must be of all material facts and information that could affect the decision to give the consent Examples of informed consent In Phipps v Boardman [1967] 2 AC 46; [1966] 3 All ER 721 the House of Lords made comments on the question of consent to a transaction involving a solicitor who owes fiduciary duties to clients who are trustees of a trust. In such cases there is no doubt that the unanimous consent of the trustees is necessary: Phipps v Boardman at AC 128; All ER 759, per Lord Upjohn. However, in that case, Viscount Dilhorne at AC 93; All ER 737 and Lord Cohen at AC 104; All ER 744 suggested that the consent of the beneficiaries to the trust is also necessary Examples of informed consent Director–company relationship, the House of Lords in Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1967] 2 AC 134; [1942] 1 All ER 378 held that, for a director to escape liability for breach of fiduciary duties, the consent of the company through a resolution of shareholders at a general meeting of the company was required Queensland Mines Ltd v Hudson (1978) 18 ALR 1, the Privy Council upheld the validity of the consent of a company given by its board of directors Unauthorised remuneration Reading v R [1951] AC 507 Reading was a sergeant in the English army stationed in Egypt. He accompanied civilian trucks through security checkpoints in order to assist them in transporting contraband goods. In return he was paid for his assistance. The court ruled that Reading owed fiduciary duties to the Crown and the amount recoverable by the Crown was the full amount that Reading had received for his services. Assuming a double character In Armstrong v Jackson [1917] 2 KB 822, Armstrong instructed Jackson, a stockbroker, to buy shares in a certain company. Jackson transferred his own shares in that company to Armstrong. The court ruled that Jackson had breached his fiduciary duties to Armstrong A broker who is employed to buy shares cannot sell his own shares unless he makes a full disclosure of the fact to his principal, and the principal, with a full knowledge, gives his assent to the changed position of the broker ... [A] broker who secretly sells his own shares is in a wholly false position Benefits derived by fiduciary to the exclusion of another Cases in this category involve a fiduciary, acting within the scope of his or her undertaking, deriving a profit or benefit that should have gone to the person to whom the fiduciary duties were owed Benefits derived by fiduciary to the exclusion of another Chan v Zacharia (1984) 154 CLR 178 at 199; Deane J said: Stated comprehensively in terms of the liability to account, the principle of equity is that a person who is under a fiduciary obligation must account to the person to whom the obligation is owed for any benefit or gain (i) which has been obtained or received in circumstances where a conflict or significant possibility of conflict existed between his fiduciary duty and his personal interest in the pursuit or possible receipt of such a benefit or gain or (ii) which was obtained or received by use or by reason of his fiduciary position or of opportunity or knowledge resulting from it. Benefits derived by fiduciary to the exclusion of another Two sub-rules, namely: 1. cases in which a fiduciary is not to derive a profit or benefit that should have gone to the person to whom fiduciary duties are owed (the breach of undertaking sub-rule); and 2. cases in which a fiduciary is not to gain a profit or benefit through the misuse of his or her position as a fiduciary (the misuse of position sub-rule). The breach of undertaking subrule The purpose of this sub-rule is to prevent a fiduciary acting for his or her own benefit in a transaction undertaken for the benefit of the person to whom he or she stands in a fiduciary relationship. Critical to determining if there has been a breach of fiduciary duties is the determination of the scope of the fiduciary’s undertaking. The relationship between the parties must be examined to ascertain the scope of the fiduciary’s duties before any question of breaches of fiduciary duties can be entertained The breach of undertaking subrule In Clark Boyce v Mouat [1994] 1 AC 428; [1994] 4 All ER 268, solicitors acted for a woman who mortgaged her property to cover her son’s debt to a finance company. The same solicitors acted for the son. The solicitors had disclosed the potential conflict between their respective duties to the woman and her son on a number of occasions. The solicitors’ advice to the woman that she obtain independent legal advice was never acted upon by the woman. The woman claimed a breach of fiduciary duties by the solicitors, arguing that they should have advised her on the wisdom of the transaction and investigated the son’s financial position before she executed the mortgage. In the circumstances, the Privy Council rejected the woman’s claim on the ground that the solicitors’ undertaking to the woman extended only to giving legal advice. The breach of undertaking subrule Phipps v Boardman [1967] 2 AC 46 Boardman acted as a solicitor for a trust. He attended the annual general meeting of Lester & Harris Ltd, a company in which the trust had a substantial shareholding. Boardman and Tom Phipps, one of the beneficiaries under the trust, were unhappy with the state of the company. Together they planned to acquire shares in the company to take over the company. Boardman was able to assess the viability of the takeover because of information about the company he gained whilst acting as solicitor for the trust. Boardman advised the beneficiaries of the trust of these plans and no objection was made by any of them. He also had the consent of two of the three trustees, the third, being senile, was not advised of these plans. The breach of undertaking subrule The takeover was successful and resulted in profits to the trust in relation to its shareholding in the company as well as for Boardman and Tom Phipps in relation to the shares they had personally acquired. John Phipps, one of the beneficiaries under the trust, sought an account of the profits made by Boardman and Tom Phipps on the grounds of breach of fiduciary duties. By a bare majority the House of Lords held in favour of John Phipps. The breach of undertaking subrule The majority Law Lords (Lords Cohen at AC 100–3; All ER 741–3; Hodson at AC 109–11; All ER 747–8; Guest at AC 114–17; All ER 750–2) all held that the information obtained by Boardman was trust property and that it was irrelevant that the trustees of the trust were in no position to acquire the shares in the company for the trust. Because there was a conflict, or at least a possibility of a conflict, between Boardman’s duty and interest, the informed consent of the trustees was needed Misuse of fiduciary position sub-rule The purpose of this sub-rule is to prevent a fiduciary using his or her position to secure or assist in exploiting a profit-making opportunity. If a fiduciary acts in such a way he or she must account for any profit or benefit derived as a result Misuse of fiduciary position sub-rule Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1967] 2 AC 134 The directors of Regal formed a subsidiary company with the intention that Regal own all the shares in the subsidiary company. The directors sought a lease of two cinemas for the subsidiary company. However, the landlord was not prepared to grant the lease unless the subsidiary company had a paid-up capital of £5000. Because Regal did not have the necessary capital to invest £5000 in the subsidiary, the directors decided that Regal would invest £2000 and that they would invest the balance themselves. From the shares issued to them in the subsidiary, the directors made a profit. Misuse of fiduciary position sub-rule The House of Lords unanimously ruled that irrespective of whether or not Regal could have purchased the shares, the directors were liable to Regal for the profit they made: The point was not whether the directors had a duty to acquire the shares in question for the company and failed in that duty. They had no such duty. We must take it that they entered into the transaction lawfully, in good faith and indeed avowedly in the interests of the company. However, that does not absolve them for accountability for any profit which they made, if it was by reason and in virtue of their fiduciary office as directors that they entered into the transaction Misuse of fiduciary position sub-rule Victoria University of Technology v Wilson [2004] VSC 33, academics working at a university, exploited for themselves an opportunity to develop certain computer programs in circumstances where they were approached, by a former student of the university, for help with such a project whilst employed by the university. The court held that the academics breached fiduciary obligations owed to the university in that they should not have exploited the opportunity for themselves as the opportunity was one presented to the university which the university would have exploited for itself. Presumed Relationships that Carry Fiduciary Duties Trustee-beneficiary Youyang Pty Ltd v Minter Ellison Morris Fletcher – Y was discretionary trust Money was deposited in Minters’ trust account as part of a subscription agreement for shares – later the investment went bad It was argued that the breach of trust did not cause any damage HC: Monies were paid in breach of trust when the solicitors did not obtain a deposit certificate on the purchase of the shares Other events which contributed to the loss were not relevant if there was a sufficient connection between the breach and the damages Presumed Relationships that Carry Fiduciary Duties Director–company Equity and statutory rules: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) English courts have found that directors must disclose past wrongdoing to their companies, even where that wrongdoing had no negative effect on the company’s position: Item Software (UK) Ltd v Fassihi [2004] EWCA 1244. This argument was rejected in Australia in P & V Industries v Porto [2006] VSC 131, by Hollingworth J, who found that such a duty was prescriptive and outside fiduciary principles. Directors and Shareholders? Directors do not ordinarily owe fiduciary duties to shareholders: Joinery Products Pty Ltd v Imlach (2008) 67 ACSR 520. However, if ‘a special factual relationship between the directors and the shareholders’ exists, the directors may also owe fiduciary duties to shareholders: Peskin v Anderson [2001] 1 BCLC 372 at [33]; St George Soccer Football Association Inc v Soccer NSW Ltd [2005] NSWSC 1288. Thus, where directors conduct negotiations for a takeover or an acquisition of the company’s business, they are obliged to loyally promote the interests of all shareholders: Brunninghausen v Glavanics (1999) 46 NSWLR 538; Silversides Superfunds Pty Limited v Silverstate Developments Pty Limited [2008] NSWSC 904. Directors and Shareholders? Directors owe a fiduciary duty to shareholders to advise them fully and frankly of relevant information necessary to make an informed decision at a general meeting: Chequepoint Securities Ltd v Claremont Petroleum NL (1986) 11 ACLR 94. This obligation to make full and fair disclosure does not oblige the directors to give shareholders every piece of information that might conceivably affect their voting. The adequacy of the information must be assessed in a practical, realistic way having regard to the complexity of the proposal: ENT Pty Ltd v Sunraysia Television Ltd [2007] NSWSC 270. Directors to creditors? No - there do not appear to be general fiduciary obligations owed by directors to creditors: R v Spies (2000) 201 CLR 603; 173 ALR 529. Fiduciary obligations may arise in cases where the company has become insolvent, as the interests of the creditors begin to take over the interests of the shareholders, as the assets of the company effectively become the assets of the creditors as the company lurches into liquidation: Angas Law Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Carabelas (2005) 226 CLR 507; 215 ALR 110; The Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) at [4418], [4439]. Legal practitioner- client unauthorised profits Conflicts with other client Hilton v Barker Booth [2005] 1 All ER 561. This rule forbids the lawyer from entering into dealings with their clients, without the clients’ fully informed consent: Maguire v Makaronis. It also prevents the lawyer from acting for third parties, when the interests of those third parties conflict with the clients’. This is refered to as a conflict between duty and duty. Such conflicts can be avoided as long as all parties know that the same practitioner is acting for different parties to the transaction and no actual conflict of interest arises: Rigg v Sheridan [2008] NSWCA 79. What about after the retainer? Victorian cases: Spincode Pty Ltd v Look Software Pty Ltd (2001) 4 VR 501 Maguire v Makaronis (1997) 188 CLR 449 A husband and wife executed a mortgage in favour of their solicitors to secure bridging finance for the purchase of a poultry farm. The trial judge found that the solicitors did not draw the clients' attention to the fact that the solicitors were to be the mortgagees or tell them that they should obtain independent legal advice. The clients defaulted on the loan secured by the mortgage and the solicitors claimed possession of the mortgaged property. The clients sought by counter-claim a declaration that the mortgage was void. Breach of fiduciary duty – however The mortgage could not be set aside without conditioning relief upon repayment by the mortgagors of principal and interest. Otherwise the mortgagors would be left with the fruits of the transaction of which they complained. Prince Jefri Bolkiah v KPMG[1999] 2 AC 222 KPMG audited the Brunei Investment Agency (BIA) when it was chaired by B. B was later removed from his position B had also retained KPMG personally wih other litigation which gave them access to his personal financial information Later KPMG was asked by BIA to do further work. KPMG accepted and set up a Chinese wall Prince Jefri Bolkiah v KPMG[1999] 2 AC 222 HofL finds that KPMG should be injuncted There was no absolute rule that a solicitor could not act in litigation against a former client, but that the solicitor might be prevented from doing so if it were necessary to avoid a significant risk of disclosure or misuse of the confidential information of a former client. KPMG accepted that an accountant who rendered litigation support services of the type provided to B fell to be treated in the same way as a solicitor. The court's jurisdiction to intervene on behalf of a former client was based on the protection of confidential information and the duty was to keep the information confidential, not simply to take reasonable steps to do so Prince Jefri Bolkiah v KPMG[1999] 2 AC 222 Historical footnote: The Brunei government charged Jefri with embezzling $14.8b. Wikipedia reports: He denies the charges but in 2000 agreed to turn over his personal holdings to the government, in return for avoiding criminal prosecution and being allowed to keep a personal residence in Brunei. After numerous legal disputes and appeals, in 2007 Britain's Privy Council ruled that this agreement is enforceable. His various legal issues with the Bruneian state have become the most expensive legal case in British legal history The House of Lords upheld the agreement in Bolkiah v Brunei Darussalam [2007] UKPC 63 Agent - principal McKenzie v McDonald [1927] VLR 134 Pedersen v Larcombe [2008] NSWSC 1362 Beach Petroleum NL v Abbott Tout Russell Kennedy (1999) 33 ACSR 1 Partners Re Agriculturist Cattle Insurance Co (1870) LR 5 Ch App 725, at 733, James LJ said: Ordinary partnerships are by the law assumed and presumed to be based on the mutual trust and confidence of each partner in the skill, knowledge and integrity of the every other partner. As between the partners and the outside world (whatever may be their private arrangements between themselves), each partner is the unlimited agent of every other in every manner connected with the partnership business, and not being in its nature beyond the scope of the partnership. Partners After dissolved? Chan v Zacharia (1984) 154 CLR 178 – partner dissolved partnership and then exercised option for elase on the old business – constructive trustee of lease Friend v Brooker (2009) 255 ALR 601 – move from partnership to company structure Employers - Employees Warman International v Dwyer (1995) 182 CLR 544 – Bonfiglioli made gear boxes in Italy and used Warman as its agent to sell them in Australia Warman was aked to enter into a joint venture to make the gearboxes I Australia but declined Dwyer was a manager at Warman which ran the agancy side of the business. He was thinking of leaving and Warman offered to sell him the agency. He declined Before leaving he undermined Warman’s relationship with Bonfiglioli , set up a new business, and took up the joint venture with Bonfiglioli, which then took over the agency business Trial judge – breach of fiduciary duty Employers - Employees Mason C.J., Brennan , Deane , Dawson and Gaudron JJ. There is no doubt that, before leaving the employment of Warman, Dwyer had made at least a preliminary agreement to set up a joint venture with Bonfiglioli, thus supplanting Warman. Instead of attempting to enhance the relationship between Bonfiglioli and his employer, Dwyer actively sought to reduce Bonfiglioli's confidence in Warman. So much is plain from the correspondence and from the fact that Dwyer caused B.T.A. and E.T.A. to be incorporated months before he resigned in 1988. It is also plain that Dwyer made arrangements with the other staff of Warman's Queensland branch to the effect that they would leave Warman and become the staff of the new distributing agent if and when his plans came to fruition. Hence, this is a clear case of a fiduciary breaching his obligations. Employers - Employees Remedy? Account – In the case of a business it may well be inappropriate and inequitable to compel the errant fiduciary to account for the whole of the profit of his conduct of the business or his exploitation of the principal's goodwill over an indefinite period of time. In such a case, it may be appropriate to allow the fiduciary a proportion of the profits, depending upon the particular circumstances. That may well be the case when it appears that a significant proportion of an increase in profits has been generated by the skill, efforts, property and resources of the fiduciary, the capital which he has introduced and the risks he has taken, so long as they are not risks to which the principal's property has been exposed. Then it may be said that the relevant proportion of the increased profits is not the product or consequence of the plaintiff's property but the product of the fiduciary's skill, efforts, property and resources. This is not to say that the liability of a fiduciary to account should be governed by the doctrine of unjust enrichment, though that doctrine may well have a useful part to play; it is simply to say that the stringent rule requiring a fiduciary to account for profits can be carried to extremes and that in cases outside the realm of specific assets, the liability of the fiduciary should not be transformed into a vehicle for the unjust enrichment of the plaintiff Employers - Employees Result Warman was entitled to an account of profits made by the new company in its first two years of operation on the basis of the net profits of the business before tax less an appropriate allowance for the expenses, skill, expertise, effort and resources contributed by the defendants Financial adviser–client Financial and investment advisers may owe fiduciary duties: Calvo v Sweeney [2009] NSWSC 719 at [219] Daly v Sydney Stock Exchange (1986) 160 CLR 371:The duty of an investment adviser who is approached by a client for advice and undertakes to give it, and who proposes to offer the client an investment in which the adviser has a financial interest, is a heavy one. His duty is to furnish the client with all the relevant knowledge which the adviser possesses, concealing nothing that might reasonably be regarded as relevant to the making of the investment decision including the identity of the buyer or seller of the investment when that identity is relevant, to give the best advice which the adviser could give if he did not have but a third party did have a financial interest in the investment to be offered, to reveal fully the adviser’s financial interest, and to obtain for the client the best terms which the client would obtain from a third party if the adviser were to exercise due diligence on behalf of his client in such a transaction. Pilmer v Duke Group Limited (in liq) (2001) 207 CLR 165 Kia Ora Gold Corp Ltd was taking over Western United Ltd Many Kia Ora directors had an interest in Western a report by ‘independent qualified persons’ for the information of shareholders whose approval was ultimately required at a general meeting The firm of chartered accountants (Nelson Wheeler) engaged by Kia Ora had, in fact, a long history of dealing with both that company and Western United Ltd. The report asserted that the price to be paid for the shares in Western United was fair and reasonable. Pilmer v Duke Group Limited (in liq) (2001) 207 CLR 165 This was not the case, with Kia Ora paying out around $26m for $6m worth of shareholdings and thus enabling huge personal profits to be made by the Kia Ora directors who held shares in Western United. Kia Ora subsequently brought an action against the partners of the accountancy firm seeking to recover for its loss. Pilmer v Duke Group Limited (in liq) (2001) 207 CLR 165 High Court: The accountants owed no relevant fiduciary duty to K There was no prior or concurrent engagement or undertaking by any member of the accounting firm which presented an actual conflict or a real or substantial possibility of conflict in the acceptance and performance of the retainer by the provision of the report Guardians and wards Trevorrow v State of South Australia (No 5) (2007) 98 SASR 136 Bennett v Minister of Community Welfare (1992) 176 CLR 408 Countess of Bective v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1932) 47 CLR 417 Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? M(K) v M(H) (1992) 96 DLR (4th) 289 – incest by father The Supreme Court held that the relationship of parent and child was fiduciary, giving rise to a fiduciary duty to protect the child's wellbeing and health; and that incest was a breach of that duty. La Forest J Indeed, the essence of the parental obligation in the present case is simply to refrain from inflicting personal injury upon one's child Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? What is the content of the fiduciary duty of those in loco parentis? To do what is in the child’s best interests? To act loyally? Can the government be liable for the breach of duty by the parents? KLB v British Columbia [2003] 2 S.C.R. 403 Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? McLaughlin CJ: I have said that concern for the best interests of the child informs the parental [**52] fiduciary relationship, as La Forest J. noted in M. (K.) v. M. (H.), supra, at p. 65. But the duty imposed is to act loyally, and not to put one's own or others' interests ahead of the child's in a manner that abuses the child's trust. This explains the cases referred to above. The parent who exercises undue influence over the child in economic matters for his own gain has put his own interests ahead of the child's, in a manner that abuses the child's trust in him. The same may be said of the parent who uses a child for his sexual gratification or a parent who, wanting to avoid trouble for herself and her household, turns a blind eye to the abuse of a child by her spouse. Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? The parent need not, as the Court of Appeal suggested in the case at bar, be consciously motivated by a desire for profit or personal advantage; nor does it have to be her own interests, rather than those of a third party, that she puts ahead of the child's. It is rather a question of disloyalty -- of putting someone's interests ahead of the child's in a manner that abuses the child's trust. Negligence, even aggravated negligence, will not ground parental fiduciary liability unless [**53] it is associated with breach of trust in this sense…. Returning to the facts of this case, there is no evidence that the government put its own interests ahead of those of the children or committed acts that harmed the children in a way that amounted to betrayal of trust or disloyalty. Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Paramasivam v Flynn Guardian who had sexually assaulted a child under his care and control from Fiji Applicant out of time by 10 ½ years Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? In Anglo-Australian law, the interests which the equitable doctrines invoked by the appellant, and related doctrines, have hitherto protected are economic interests. If property is transferred or a transaction entered into as a result of undue influence, then the transaction may be set aside or, no doubt, the appellant may be compensated for loss resulting from the transaction; similarly if a transaction is induced by unconscionable conduct; so, in cases usually classified as involving fiduciary obligations not to allow interest to conflict with duty, the interests protected have been economic. If a fiduciary, within the scope of the fiduciary obligation, makes an unauthorised profit or takes for himself or herself an unauthorised commercial advantage, then the person to whom the duty is owed has a remedy Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? All those considerations lead us firmly to the conclusion that fiduciary claim, such as that made by the plaintiff in this case, is most unlikely to be upheld by Australian courts. Equity, through the principles it has developed about fiduciary duty, protects particular interests which differ from those protected by the law of contract and tort, and protects those interests from a standpoint which is peculiar to those principles. The truth of that is not at all undermined by the undoubted fact that fiduciary duties may arise within the relationship governed by contract or that liability in equity may coexist with liability in tort. Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? To say, truly, that categories are not closed does not justify so radical a departure from underlying principle. Those propositions, in our view, lie at the heart of the High Court authorities to which we have referred, particularly perhaps, Breen. It follows that Gallop J was justified in concluding that he was not persuaded that the appellant’s claim based on breaches of fiduciary owed by the respondent to the appellant had real prospects of success Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Williams v Minister, Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (2000) Aust Tort Reports 81-578 The appellant, in seeking an application for an extension of time to bring an action against the Aboriginal Welfare Board, claimed damages in tort as well as claiming equitable relief. On the basis of her wardship, the Plaintiff argued that the Board owed her a fiduciary duty as to her custody, maintenance and education. This claim was rejected at first instance, but was allowed on appeal Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Kirby P - The Board was, in my view, arguably obliged to Ms Williams to act in her interest and in a way that truly provided, in a manner apt for a fiduciary, for her ‘custody, maintenance and education’. I consider that it is distinctly arguable that a person who suffers as a result of a want of proper care on the part of the fiduciary, may recover equitable compensation from the fiduciary for the losses occasioned by the want of proper care; cf Norberg v Wynrib [1992] 4 WWR 577 at 606; (1992) 92 DLR (4th) 499. In other jurisdictions, compensation for breach of fiduciary duty has been held to include recompense for the injury suffered to the plaintiff’s feelings: see, eg, Szafer v Chodos (1986) 27 DLR (4th) 388; McKaskell v Benseman [1989] 3 NZLR 75. Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Cubillo v Commonwealth - stolen generation On appeal the Full Federal Court (Sackville, Weinberg and Hely JJ) concluded, after having considered the appellant’s statutory claims, that the claim based in breaches of fiduciary duties “faced insurmountable obstacles.” Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? The second obstacle is that, in any event, the appellant’s claims are, to the use the language of Paramasivam v Flynn, within the purview of the law of torts. As the High Court has held, there is no room for the superimposition of fiduciary duties on common law duties simply to improve the nature and extent of the remedies available to an aggrieved party. If it had been the case that the removal and detention of the appellants were not authorised by the Ordinances (or otherwise justified by law), those who caused the removal or detention would be guilty of tortious conduct and liable at common law. There would be no occasion to invoke fiduciary principles Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Webber v State of New South Wales [2003] NSWSC 1263 Ward of the state sexually and physically assaulted Any breach of fiduciary duties which might give rise to equitable compensation would be confined to instances where the fiduciary acts for, or exercises a discretion on behalf of another party; where the fiduciary is concerned with economic or proprietorial rights; where the fiduciary‘s duties are proscriptive rather than prescriptive and where the breaches of duty are not an alternative to those arising out of tort, contract or common law Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Tusyn v Tasmania [2004] TASSC 50 - sexual abuse in foster care Blow J found that a fiduciary relationship existed between a guardian and ward but that “ … it does not necessarily follow that the guardian owes the ward a fiduciary duty to take reasonable care of the ward’s physical safety” Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? SB v State of New South Wales [2004] VSC 514 The Plaintiff, who had been placed as an infant with a foster family, was sexually abused by her foster father for some years. When this was discovered, the Plaintiff, then just sixteen years of age, was sent by the Department to live with her father whom she barely knew. She was then sexually abused and isolated by her father over a period in excess of ten years. As a result of the incestuous relationship the Plaintiff gave birth to two children. Parents/Guardians and Children in situations of abuse? Why the repeated failure of equity to become involved? Aren’t the doctrinal reasons for not expanding equitable roles the same arguments that failed in 1980s when equity expanded into commercial relationships What of equity’s much vaunted maxims of never letting a wrong lie without a remedy? Equity acting personally? None of the economic arguments apply Commercial relationships Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corporation United Dominions Corporation v Brian John Alexander’s Clubs Pty Limited v White City Tennis Club Limited (2010) 241 CLR 1 This case concerned an option to purchase part of the land at the famous White City tennis grounds from NSW Tennis Association (NSW Tennis). NSW Tennis wished to sell the land after alternative facilities had been built for the Sydney Olympics. Various parties ran tennis activities on the land, including the White City Tennis Club (The Club). John Alexander’s Clubs Pty Ltd (JACS) was interested in purchasing the land and entered into an agreement with the Club called a ‘memorandum of understanding (MOU)’ which formalized their intention to work together to create a new tennis club. The MOU noted that JACS promised that it would seek to obtain an option to purchase the land (or part of it) from Tennis NSW. Later, the land ownership changed hands. The new owners granted JACS an option to purchase which allows JACS or another nominate entity the right to exercise the option (the Third White City Agreement). The Club was a party to this agreement and agreed to JACS’ option being unconditional. Soon after, disputes arose between JACS and the Club. JACS sought to terminate the MOU on the grounds that the Club had repudiated it. JACS nominated a company called Poplar Holdings Pty Ltd (Poplar) to exercise the option and it became the owner of the land. The Club argued that JACS had breached its fiduciary obligation to the Club and that Poplar held the land on constructive trust for the Club Commercial relationships HC – no fiduciary duty Here the contracts to which JACS and the Club were parties are important in assessing whether JACS was bound by a fiduciary duty in relation to its exercise of the cl 8 option. The MOU obliged JACS to obtain an option, and exercise it in a certain way and on certain conditions. Before the First White City Agreement, JACS had not been able to obtain an option to buy part of the White City Land. By that agreement, and the Second and Third White City Agreements, it obtained an option, and the Club obtained an additional option after the JACS option expired. The Club, as party to the Third White City Agreement, consented to the unconditional nature of JACS’s option. The Club could have bargained for more precision in cl 8, using its ability to refuse to agree to surrender the lease. It apparently did not. The Club was not relying on representations by JACS. It was not overborne by some greater strength possessed by JACS. It was not depending on JACS to carry out dealings of which the Club was necessarily ignorant. It was not trusting JACS to do anything. What JACS and the Club did in relation to the Third White City Agreement and the exercise of JACS’s option under cl 8(a), they did consulting their own interests, with knowledge of what the other was doing. Doctors and patients Breen v Williams (1996) 186 CLR 71 at 108; 138 ALR 259 at 285. Does a doctor owed his patient a fiduciary duty to disclose a patient's medical records to her? Moore v Regents of the University of California 793 P 2d 479 (1990) - profits Doctors and patients The High Court held that it was impossible to establish any conflict of interest and duty, unauthorised profit or loss in relation to a doctor denying a patient access to the doctor’s medical records. Accordingly, the court held the doctor’s refusal to give such access did not amount to breach of any fiduciary obligation. Doctors and patients Dawson and Toohey JJ said: "... it is the law of negligence and contract which governs the duty of a doctor towards a patient. This leaves no need, or even room, for the imposition of fiduciary obligations. Of course, fiduciary duties may be superimposed upon contractual obligations and it is conceivable that a doctor may place himself in a position with potential for a conflict of interest - if, for example, the doctor has a financial interest in a hospital or a pathology laboratory - so as to give rise to fiduciary obligations ... . But that is not this case Crown and Indigenous Peoples Courts in a number of jurisdictions have discussed the existence of fiduciary duties owed by the Crown to aboriginal peoples. The existence of such fiduciary duties stems from the recognition that aboriginal peoples, as the original occupiers of land, have special rights that are protected by the imposition of fiduciary duties upon the Crown in the way government power affecting the interests of aboriginal peoples is exercised. The notion of the Crown’s fiduciary duties to its aboriginal peoples is most developed in Canada. Crown and Indigenous Peoples s 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 which stipulates: The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed. Crown and Indigenous Peoples Guerin v R (1984) 13 DLR (4th) 321 at 334 The conclusion that the Crown is a fiduciary depends upon the further proposition that the Indian interest in the land is inalienable except upon surrender to the Crown. An Indian band is prohibited from directly transferring its interest to a third party. Any sale or lease of land can only be carried out after a surrender has taken place, with the Crown acting on behalf of the band’s behalf. ... The surrender requirement, and the responsibility it entails, are the source of a distinct fiduciary obligation owed by the Crown to the Indians. Crown and Indigenous Peoples Wewaykum Indian Band v Canada [2002] 4 SCR 245 – two bands of the Laich-kwiltach First Nation claimed Indian reserves granted by Crown under an Act The nature and importance of the appellant bands' interest in these lands prior to 1938, and the Crown's intervention as the exclusive intermediary to deal with others, including the province, on their behalf, imposed a fiduciary duty on the Crown but there is no persuasive reason to conclude that the obligations of loyalty, good faith and disclosure of relevant information were not fulfilled Crown and Indigenous Peoples R v Sparrow (1990) 70 DLR (4th) 385 Delgamuukw v British Columbia (1997) 153 DLR (4th) 193 R v Marshall (1999) 177 DLR (4th) 513 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 Toohey J, at 199–205 Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 .Brennan CJ, in dissent, found that the Crown’s power to extinguish native title did not, by itself, give rise to fiduciary duties Crown and Indigenous Peoples Thorpe v Commonwealth (No 2) (1997) 144 ALR 677 The result is that whether a fiduciary duty is owed by the Crown to the indigenous peoples of Australia remains an open question. This Court has simply not determined it. Certainly, it has not determined it adversely to the proposition. On the other hand, there is no holding endorsing such a fiduciary duty, still less for the generality of the claim asserted in the first declaration in Mr Thorpe's writ. Crown and Indigenous Peoples Bodney v Westralia Airports Corporation Pty Ltd (2000) 180 ALR 91 – Lehane J In my view, the foregoing discussion leads to two conclusions. One is that the authorities from other jurisdictions do not provide a firm basis for the assertion of a fiduciary duty of the kind for which the second applicants contend. The other is that the tendency of authority in the High Court - including, significantly, Breen - is against the existence of such a duty. Crown and Indigenous Peoples That, of course, does not mean that circumstances will not arise in which the Crown has fiduciary duties, owed to particular indigenous people, in relation to the alienation of land over which they hold native title. Nor does it mean that where, in particular circumstances, a duty of that kind is breached (or a breach is threatened) a constructive trust might not appropriately be imposed. But the second applicants' pleading does not, in my view, allege facts which would establish a fiduciary duty, on the part either of the State or of the Commonwealth, requiring either the State or the Commonwealth not to participate as they did (or in the manner in which they did) in the transactions as a result of which the Commonwealth obtained title to the land incorporating the claim area. When do the duties end? Generally they will cease when the relationship has been terminated. However, in certain situations fiduciary obligations are owed after the relationship has ended. Thus, in Chan v Zacharia (1984) 154 CLR 178; 53 ALR 417, although a partnership had been dissolved, the partners still owed fiduciary obligations to each other until the partnership had been formally wound up.