Abstract

advertisement

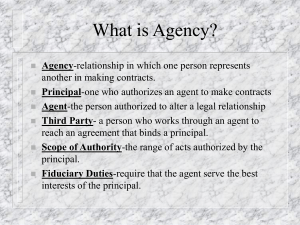

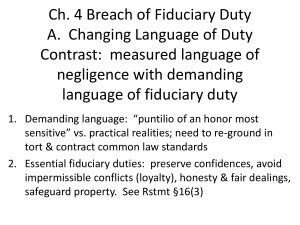

Fiduciary Duties and Moral Blackmail Simon Keller ABSTRACT When you have a fiduciary duty to someone, you have a duty to act in her best interests. In different contexts, the beneficiary’s “best interests” are differently defined. Sometimes, the relevant interests are very narrow; your duty may be merely to maximize the beneficiary’s return on a financial investment or to get her the highest possible price for her house. Sometimes, the relevant interests encompass an aspect of personal well-being; you may have a duty to serve the beneficiary’s physical and mental health. And sometimes, the relevant interests are all-encompassing; you may have a fiduciary duty to the whole person, to serve her best interests in the broadest and deepest sense. On the most plausible accounts of the ethics of special relationships, in order to honor a fiduciary duty to a whole person you must become vulnerable to a certain value: perhaps the value of the person herself, perhaps the value of your relationship with her. A consequence is that fiduciary duties of this kind cannot be easily left behind, psychologically or ethically. Where such fiduciary duties are assigned in professional contexts, and sometimes in family contexts, they can generate moral requirements that outrun the intended legal boundaries of the duty. A nurse with a fiduciary duty to a patient, for example, may come to have moral duties that go beyond the strict professional duties of a nurse and that remain after the nurse-patient relationship has ended. When a person is assigned a fiduciary duty that requires responsiveness to a whole person, she can be morally restricted in her ability to exercise her rights, and in her ability to act in her own best interests. In certain contexts, when a person is given fiduciary duties she becomes vulnerable to moral blackmail.