August

advertisement

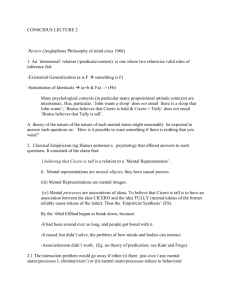

Today’s Lecture • A comment about your final Paper • Third in-class quiz and grade spreadsheet • Revisiting comments on Functionalism • Thomas Nagel • Comments about your Third Assignments A comment about your final Paper • I am giving you a bonus day of grace to get your final Paper in to me. • Three things to note about this extra day of grace: • (1) It means that IF you get your paper to me, or the assignment drop box, by 4:00 p.m. on August 11th, THEN you will not receive any late penalties for your paper. • (2) This extra day of grace only applies to your Paper. • (3) Technically, this does not change the due date for the paper (which remains August 8th). • (4) If you have any extra day s of grace remaining you can add them to this bonus day. Third in-class quiz and grade spreadsheet • Do remember that due to my oversight in not giving a third in-class quiz, each of you have received an automatic ‘2 out of 2’ for the ‘quiz that wasn’t’. • On Wednesday I am placing a randomized grade spreadsheet on the course website (look for your grades under the columns associated with your student ID number). Please check to ensure that the data matches what you have. If there are any discrepancies, come and see me. Revisiting comments on Functionalism • Functionalism contends that an internal state of an individual counts as a type of mental state if it performs the relevant causal role, in relation to other states of the central nervous system or non-neuronal physiological processes, and is causally efficacious in contributing to the subsequent behavior of the organism that possesses it (see FP, p.391). • Metaphysical Behaviorism, remember, reduces mental states to dispositions to act. • Logical Behaviorism, remember, reduces talk of mental states to talk of dispositions to act. From “The Nature of Mental States”: IV • Problems facing Metaphysical Behaviorism: • (1) They need to properly specify the relevant behavioral dispositions for the relevant psychological state without appealing to the very state itself (FP, p.431). • (2) It seems conceivable to imagine two individuals, one being in pain while the other is not in pain, exhibiting relevantly similar behavior (FP, p.432). • (3) It seems more plausible to explain behavior with reference to internal causally efficacious psychological states than to identify said states with the behavior itself (FP, p.432). Revisiting comments on Functionalism • For the behaviorist, the mind, human or nonhuman, is a black box that remains outside of the domain of empirical psychology. • The Functionalist rejects this ‘treatment’ of the mind, but keeps some of the behavioral orientations of behaviorism. In particular, the conception of belief (and other mental states possessing intentional content [where ‘intentional content’ refers, for our purposes, to the information about something contained in a given state]) at work in functionalism involves causal efficacy (a belief properly so called has, by its very nature, behavioral import) and is individuated (identified as the kind of belief it is) based on its interaction with either other mental states contained in the relevant individual’s mind or with the individual’s non-mental physiological processes or mechanisms. Revisiting comments on Functionalism • Just as neither kind of Behaviorism seems to deal well with, among other things, claims of sensation, critics of functionalism contend that it (i.e. functionalism) cannot accommodate consciousness. Thomas Nagel’s “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” is, in part, an attack on contemporary theories of mind on this very issue (FP, p.476). Revisiting comments on Functionalism • Do remember that a rejection of type-type MindBrain Identity Theory does not require one to reject a type-token Mind-Brain Identity Theory. In a typetoken Identity Theory, mental states are, in the case of humans and other terrestrial animals, identical to actual states in the relevant central nervous systems, though they may be instantiated in very different biological systems or forms of life (i.e. that lack central nervous systems) elsewhere in the universe. Thomas Nagel • Thomas Nagel is a contemporary American philosopher who was born in 1937. • Nagel’s motivating concern in philosophy is exploring the relationship between first person and third person accounts/perspectives of ourselves and the world (broadly construed), and, perhaps more importantly, the epistemic status of first person accounts/perspectives. In particular, Nagel challenges the view that third person accounts/ perspectives are always to be preferred over first person accounts (FP, p.475). Thomas Nagel • It is not that Nagel rejects the value of third person accounts/perspectives or the value of objectivity associated with such view points. Rather, Nagel contends that first person accounts/perspectives take preeminence in certain contexts of belief (FP, pp.475-76). Thomas Nagel • Important things to note about the reading: • (1) Nagel is not disavowing Physicalism (or Metaphysical Materialism) (FP, p.477). • (2) He is rejecting BOTH ontological AND theory reduction concerning mental states (FP, pp.476-77). • (3) Nagel rejects the Cartesian view that mental states are “radically private” (FP, p.477). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” Introductory remarks • Present contemporary physicalist theories of mind cannot explain consciousness, or provide a reductionist analysis of conscious mental phenomena (FP, pp.478-79). • Consciousness, or conscious experience, occurs in many terrestrials life forms (FP, p.479). • It probably occurs in life-forms in other parts of the universe (FP, p.479). • It is difficult to specify the general justificatory grounds for ascribing consciousness (FP, p.479). • It is unlikely that the consciousness of an experience has particular behavioral consequences (FP, p.479) “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” Introductory remarks • Consciousness, according to Nagel, involves an important (read essential) subjective component. • “[F]undamentally an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism - something it is like for the organism” (FP, p.479 [emphasis the author’s]). • Do note that Nagel is not arguing that all mental states are conscious. This means that there are mental states that do not have a subjective component (essential or otherwise). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Present contemporary physicalist theories of mind cannot explain consciousness, or provide a reductionist analysis of conscious mental phenomena for the following reasons: • (1) Contemporary physicalist theories of mind are logically consistent with minds that lack consciousness (FP, p.478). • (2) The explanatory frameworks for contemporary physicalist theories do not provide explicit physicalist analyses of conscious experience (FP, p.479). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • (3) Without an idea about the nature of subjective experience, we cannot specify what needs to be explained by a physicalist theory of mind. Without such a specification, we cannot declare the adequacy of any given physicalist theory of mind. We still lack an adequate account of what subjective experience is (FP, p.480). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • A methodological worry about epistemic objectivity, mind and physicalism: • (1) Epistemic objectivity involves the abandonment of subjectivity, in particular the abandonment of “a single point of view” (FP, p.480). • (2) Conscious experience is essentially subjective (i.e. it essentially involves a single point of view). • (3) So it seems unlikely that we can develop an objective physicalist theory of conscious experience (FP, p.480). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Nagel’s Bat example: • The differences between bat and human physiology and sensory faculties makes it impossible to simply extrapolate from our own experiences when trying to describe what it is like to be a bat. • If we are to adequately understand bat (conscious) experience it would appear that we cannot depend on our usual methods of extrapolation (FP, p.481). • (1) It won’t be enough to merely imagine possessing the relevant physical structures, as this only gives us a way to understand what it would be like for us “to behave as a bat behaves” (FP, p.481). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • (2) We cannot take this a step further and simply imagine possessing the neurophysiology of the bat. After all this will only work if we can imagine what it would be like to possess the relevant internal neurophysiology of the bat, and this is the problem that got us here in the first place. Any talk of undergoing such a transformation will make little sense (FP, p.481). • It would seem, then, that the only way to know the experience of a bat is to be one (FP, p.481). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Note that Nagel doesn’t deny that we can say some very general things about the types of experiences a bat must have. • We can reasonably suppose, given its physiological structures and behavior, that “bats feel some version of pain, fear, hunger, and lust, and that they have other, more familiar types of perception than sonar” (FP, p.481). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • We can see, then, that something seems to be lost when we abstract away from, or are unable to imagine, the experience of the individual whom we regard as minded. • This, Nagel suggests, will get worse if we think of, or even encounter, extra-terrestrial life (FP, p.481). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • He suggests that we do not have to leave our own species for this problem to arise. He asks us to imagine encountering a human that is both deaf and blind, and has been so since birth. • “The subjective character of the experience of a person deaf and blind from birth is not accessible to me ... nor presumably mine to him. This does not prevent us each from believing that the other’s experience has such a subjective character” (FP, p.482). • What do you think? What does this show about theorizing about mind? • Can we believe that there are facts of the universe that lie, and will forever lie, outside of our understanding and knowledge? Is this an intelligible belief (FP, p.482)? “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Nagel’s “Intelligent bat or Martian” example: • He asks us to imagine a sapient bat or Martian trying to extrapolate from their own experience in order to understand our own. Given that they are radically different from us in their neurophysiology, they will have an analogous problem to our own when we are trying to understand an ordinary bat. But they should not adopt the epistemic principle that ‘We cannot meaningfully believe that there are facts which we cannot conceive exist’ and thus conclude that we only enjoy rather general types of experience, if we enjoy any experience at all. After all, such an epistemic principle would lead them to a false belief about us (and many animals like us), namely that we do not possess subjective experiences (FP, p.481). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Nagel wants to draw the following conclusion from the discussion thus far: • “Whatever may be the status of facts about what it is like to be a human being, or a bat, or a Martian, these appear to be facts that embody a particular point of view” (FP, p.483). • There are facts, then, that to be objectively known require first person experience (FP, p.483). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Note, Nagel does not think that this entails a view that consciousness is radically private. It merely points out the limits of extrapolation as we move across relevantly similar to dissimilar taxa. • The closer the subject of study is to ourselves, the easier it is to extrapolate the nature of their subjective experience. Thus we can have objective knowledge of subjective events. • What is clear is that by not accounting for subjectivity in human (and nonhuman) minds we do not, and cannot, provide an exhaustive analysis of mental phenomena (FP, p.483). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • The problems gets worse, however. • To be able to develop an adequate and objective theory of mind we need to suppose that mental phenomena have both subjective and objective characteristics AND either that the subjective characteristics have objective markers or we can extrapolate from our own cases to the content of these subjective experiences (FP, pp.483-84). • But how do we adequately defend this supposition? “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • These problems seems to point to a relevant dissimilarity between mind and successful reductionist programs in other areas of knowledge. • In the physical sciences we adopt a more objective viewpoint by abstracting away from subjective views points, thus allowing for a purely physicalist treatment of the phenomena under discussion. “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • But the nature of conscious mental phenomena seems to preclude this path towards more objectivity (or at least this view of objectivity) (FP, pp.484-86). • Though these considerations do not give us what we would need to conclude that physicalism is false (FP, p.485), we must admit that, at this point, we “do not have the beginnings of a conception of how it might be true” (FP, p.486). • For Nagel, this is not an incoherent claim. “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • We do not require understanding to have evidence for the truth of a hypothesis (FP, p.486). • Nagel attempts to defend this claim with his “Caterpillar in a box” thought experiment. • Imagine that we do not know that caterpillars metamorphosize into butterflies at some point in their ontogeny. We lock a caterpillar in a sealed sterile container in which it survives until the metamorphosis takes place. Upon discovery of the butterfly and no caterpillar when we open the box we can reasonably infer that the butterfly was, in some sense, the caterpillar even though how this is the case alludes us (FP, p.486). “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” • Nagel likens this to our present understanding of mind. We know the mind is physical in some sense. After all mental states have causes and produce effects. • We do not yet know how this is possible (FP, p.487). Comments about your Third Assignments • (1) Take care not to make claims that are open to a criticism or objection already raised in your readings (or in lectures), or take care to respond to such criticisms or objections in the course of your discussion. • (2) If you disagree with a philosopher’s position, you need to provide adequate reasons for rejecting it. • (3) Don’t claim something for which you offer insufficient justification. • (4) Beware of adopting a non-critical stance towards sources outside of your course texts. Comments about your Third Assignments • (5) Don’t beg the question against your interlocutor. • (6) Make sure you accurately portray the position of the philosopher you are criticizing. • (7) Take care to avoid merely repeating a position (or critical stance) I have advocated in class. • (8) Make sure to proof read your assignment before submitting it.