Health, Nutrition and Feeding

Language: Individual differences

Daniel Messinger, Ph.D.

Language overview review n n n n

What is the normative course of infant language development?

How do infant cries develop (directed and undirected)?

What are the stages of development of non-cry vocalizations?

What are some early milestones of verbal development (verbal development involves words)?

2

Perspective n Last time

– Features of language that all infants develop

– Focus on production: speech n This time

– How infants differ in learning language n Differences in learning to hear a first language n

Differences in learning to talk a first language n Autism and deafness

3

Today’s questions n How does the ability to distinguish between nonnative speech sounds change in the first year?

– What does this mean about development?

– Can distinctions between non-native sounds be taught? n How is language experience associated with later child language competence and IQ? n How is socioeconomic status associated with differences in language experience?

n What does cochlear implantation teach us about language development?

4

Consider the spoken tokens of

“doll.” n To a Hindi speaker, the difference between the “d” sounds in “this doll” versus “your doll”—a phonetic contrast between a dental

[d ̪ al] versus a retroflex [ɖal], respectively— would signal two possible word forms

(either lentils or branch). n In English, both of those “d” sounds signal just one possible word form—phonetically labeled as an alveolar [dal].

5

Different languages provide different phonetic experiences

6

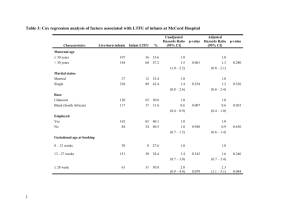

What’s going on?

n English-learning infants hear Hindi contrast better than

English-speaking adults n Almost as well as adult Hindi-speakers

40

30

20

10

0

60

50

100

90

80

70

Dentral vs. retroflex "t"

Hindi Adults

Infants

English Adults

7

Distinguishing between nonnative speech sounds in 1st year n n n

At birth, infants are capable of discriminating all phonetically relevant differences in the world’s languages

– They perceptually partition the acoustic space underlying phonetic distinctions in a universal way.

By 6 months of age, infants raised in different linguistic environments show an effect of language experience.

Their representations are becoming language specific

8

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

How does this develop?

n Infants lose this ability in the first year of life, especially toward one year of age

6-8 Months

8-10 Months

10-12 Months

Dentral vs. retroflex "t"

9

What this mean for development n n n

Very young infants can discriminate a wide range of phonetic contrasts in a variety of languages

Between 1 & 12 months, infants

– increase knowledge of which syllables follow which in their native language

– but lose ability to make contrasts that do not occur in their native language n

/r/ vs. /l/ . /b/ vs. /v/ . Te’ vs. te, tu’ vs. too

Development involves relatively permanent change, but not always improvement in all things.

10

Parallels in speech production

•

•

Infant babbling shows little influence of native language.

Once the infant forms his/her 1 st words than the sounds produced conform more closely to those of the native language n This corresponds to the stage at which infants begin to show language-specific sensitivity (10-12 months).

11

Possible roles of experience

Induction – prior experience with a language is necessary because perceptual capability depends entirely on environmental input

Attunement – experience makes possible the full development of a capability.

Facilitation – experience effects only the rate of development of a capability.

Maintenance/loss – the ease in which a capability is fully developed before the onset of experience, but experience is necessary to maintain the capability.

Maturation – development of a capability independent of experience

12

Perceptual Magnet Effect n Instances of sounds that belong to a category are drawn toward the Prototype.

n Physical (acoustic) vs. perceptual maps

– the latter differ for speakers of different languages

13

Can distinctions between nonnative sounds be taught?

n Cheour has experimentally produced this

“development” n In sleeping neonates n Using changes in neural responses to sounds as an outcome variable

• http://www.med.cornell.edu/news/press/2002/feb_22_ newborn.html

14

How sleeping babies learn n

The babies had electrodes placed on their scalps, and speakers near their heads gently played a randomized sequence of two similar Finnish vowel sounds as they slept: a "standard" sound, /y/, and a

"deviant" sound, /i/.

15

Mismatch Negativity (MMN) n n

“ when the brain hears the standard sound, there is a certain response in the brain, and when it hears the deviant sound, there is another response.

Subtracting the responses to the deviant from the responses to the standard produces the MMN.”

16

Training n n n

No initial MMN for any group (N=15).

Over the following night, for between two-and-a-half and five hours, the experimental group had a "training" session of exposure to the two sounds.

–

/y/ vs. /i/.

One control group did not have this exposure, and the other control group heard two different sounds, /a/ and /e/.

18

Results n n n

The experimental group showed significant mismatch negativity to the deviant sound.

The babies had learned to distinguish between these two Finnish vowels.

–

Persisted for at least 24 hours.

The two control groups showed no MMN to the deviant sound.

19

Conclusion n n

"We have shown that newborns can assimilate auditory information while they are sleeping, suggesting that this route to learning may be more efficient in neonates than it is generally thought to be in adults."

•

Cheour

Is this learning?

22

23

Reviewing the power of language o More maternal vocalizing at 1 month o Associated with vocalizations at 8 & 24 months and with socioeconomic status o Also predicts greater adolescent intelligence o R 2 = .22 for gazing and maternal vocalizations

120

110

100

90

80

Long Infant

Fixation /

Low Maternal

Vocalization

Long Infant

Fixation /

High Maternal

Vocalization

Short Infant

Fixation /

Low Maternal

Vocalization

Short Infant

Fixation /

High Maternal

Vocalization

26

Overview n Socioeconomic differences in how folks talk to their kids n What impact might it have?

n How is language experience associated with later child language competence and IQ?

27

Socioeconomic status differences in language experience are associated with later child language competence and IQ n Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children.

Hart &

Risley (1995). Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Publishing Co n

Some text from summaries by Susan Brunner, Dahra Jackson, and Amy Vaughan

28

Participants n n

Longitudinal project from 9-10 months infant age up until 2-2 ½ years later

–

–

–

42 families observed for one hour every month, at home, in natural settings recruited from birth announcements, friends and families at University pre-school, WIC meetings, and state records all but 8 families were intact, all but one had a male figure involved

13 upper SES, 10 middle SES, 13 lower SES, and

6 families on welfare; all “well-functioning”

29

Data collection n Observers transcribed and audio-recorded all verbalizations and interactions that would have an effect on another person; never interacted with child, but responded to parents

–

–

Observers assigned to families for entire study, when possible, and similar to family in terms of background no drop-outs after first year, reliability on coding and observations was adequate

– words coded as part of speech, episodes coded by type, and speaker coded; dictionaries compiled for each speaker (all on computer)

30

Commonality n Despite how strikingly different the families were in how much talking and interaction typically went on in the home, just socializing during everyday activities was sufficient for all children (regardless of SES) to learn to talk by age 3.

31

42 Families and the Differences

Among Them n n differences observed in family language style: parents’ language seemed to reflect the number and variety of behaviors they had for dealing w/ their children some families talked more than others, and this was variable within families from month-tomonth, but stable over the 3 years

– birth order and family size affected the amount of talk each child received, but did not affect the total amt. of talk

32

n SES seemed to make the biggest contribution to both amount of talk and time spent in interactions, with hi SES at an average of 482 wds/hr and 48 mins/hr, and welfare families at

197 wds/hr and 17 mins/hr

33

Language and SES (class) n n n

Children from all backgrounds have the same kinds of everyday language experiences.

But more economically advantaged children differ in the amount of these experiences; it is the frequency that matters.

More opportunities for learning language occur when children engage in many and varied interactions with other people; families tend to be consistent in the opportunities they provide for their children.

34

Talk that teaches talk n n n n n

THEY JUST TALKED

– parents talked beyond what was needed to provide care

THEY LISTENED

– To add information and prompt elaboration

THEY TRIED TO BE NICE

– When enforcing a rule

THEY GAVE CHILDREN CHOICES

THEY TOLD CHILRESN ABOUT THINGS

– Things worth noticing or remembering (Halloween)

35

Quantity of language: Nouns, adjectives, and adverbs to child

36

Being positive n Repetitions, extensions, expansions, confirmations, praise, approval over all feedback

(including imperatives, criticisms, etc).

37

Relating things and events n Nouns, modifiers, and past-tense verbs divided by number of utterances per hour

38

“Can you. . . ?” n Proportion of yes/no questions over yes/no questions and imperatives

39

Responsiveness n

‘Ok’ ‘I see’ n % of responses not preceded by an initiation

40

How language experience is associated with later child IQ n

“Parenting” =

Language diversity + feedback tone + symbolic emphasis + guidance style + responsiveness n Predicts between and within SES groups

41

Language experience makes the difference

42

Implications for intervention n n n n

‘To intervene with vocabulary growth rate … increase the experiences available to the children

Limited success … ultimately the growth rates increased only temporarily.

Could easily increase the size of the children’s vocabularies, could not accelerate the developmental trajectory.’

“Removing barriers and offering opportunities and incentives is not enough to overcome the past, the transmission across generations of a culture of poverty.”

43

Is environmental influence global or specific?

n n n

We know that there are differences in language development across SES

Mothers are primary source of language-experience

Does maternal speech mediate the relation between SES and child vocabulary development?

The Specificity of Environmental

Influence: Socioeconomic Status Affects

Early Vocabulary Development Via

Maternal Speech

Erika Hoff

Maternal speech fully mediates relationship between SES and

child vocabulary!

SES -> 5% of variance in child vocabulary

SES significantly associated with maternal speech

MLU -> 22% of variance in child vocabulary

When removed, only 1% of variance explained by SES

So…there are 2 processes going on

1. SES affects maternal speech

Childrearing beliefs

Time availability

2.Maternal speech affects language growth

Provides data for child’s word-learning mechanisms

Longer utterance -> more variance in word types (richer vocabulary)

Longer utterance -> more info about meaning

Longer utterance -> richer syntax

Support environmental specificity model n Vocabulary development depends on specific properties of language experience n Implies that enriching language experience can increase vocabulary development for low-SES kids

Niparko et al., 2010

Romero

Earlier implantation, earlier language gains

Romero

Receptive Language

Romero

Expressive Language

Romero

Other findings n Higher parent-child interactions and higher socioeconomic status were associated with greater rates of language learning.

n Bilateral implantation was not associated with an increase in language acquisition.

n Gender was not associated with an increase in language acquisition.

Romero