Philadelphia Convention (1787)

advertisement

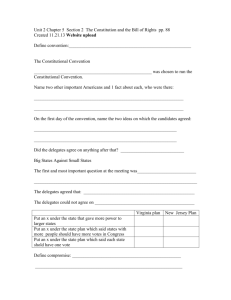

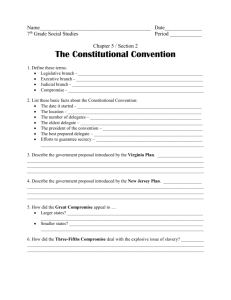

Philadelphia Convention (1787) Organizing the Convention By 1786, it was clear that the Articles of Confederation presented an ineffectual government for the union. Under the Articles, the Continental Congress had no courts, no power to levy taxes, no power to regulate commerce, and no power to enforce its resolutions upon individuals or the 13 states. In the areas where Congress did have authority, the members had no way of enforcing their powers. Further complicating matters, the Congress did not have the respect of the people it set out to serve. Individual states continued to make their own laws, particularly where taxation and commerce were concerned. Differing tariffs and trade laws made for a disorganized union, and some states even continued making their own money. The Articles of Confederation had purposely left the Congress weak, which resulted in a government that could not enforce a unified set of laws. With strong encouragement from six of the states, Congress called a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation into a more powerful document. Each state appointed delegates to attend a meeting in Philadelphia to develop a more effective and unified constitution. In total, 55 delegates from 12 states were present when the Philadelphia Convention began in May of 1787. These delegates were professional men, with over half of them lawyers, and as such they carried an aura of wealth and power. The men who attended this convention were considered youthful, with an average age of 42. Benjamin Franklin, at the age of 81, was respected as the convention’s patriarch. Many delegates had served in the Continental Congress, so they brought with them some experience regarding governmental issues. Half of the delegates had served as officers in the Continental Army and had firsthand knowledge of the Continental Congress’s financial tribulations as well as a mindset to avoid and overcome them in the new constitution. Each of the delegates came to Philadelphia with personal perspectives that influenced their actions during the convention. To some delegates, the economic aspect of the constitution was the utmost priority. For example, wealthy landowners who served as delegates to the Philadelphia Convention wanted to shape and protect property rights for themselves and other elite statesmen. Other delegates came with the idealistic notion of creating a perfect Union, while still others focused on concerns relating to sovereignty and trade relationships among states and internationally. Notably absent from the Philadelphia Convention were Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry, who had led the states to independence just eleven years prior. Some of the heroes of the war had either left the states or were not chosen as delegates by a public who understood that the need for revolution had been replaced by the need for unification. Patrick Henry agreed with the need for unity, and was in fact elected as a delegate, but he boycotted the convention believing that the outcome would not be positive. Most of the Philadelphia Convention participants were veterans of the Revolutionary War. George Washington, highly respected for his success in the war, was unanimously elected president of the convention by his peers. And James Madison, with an acute knowledge of government systems, came to be known as the “Father of the Constitution” due to his promotion of two key concepts: officials elected by the people and a preference for a large republican government. Madison’s copious notes have served historians as the most accurate and complete record of this gathering. The Philadelphia Convention got underway with a radical decision to throw out the Articles of Confederation and start fresh developing a framework for strengthening the power of the United States’ federal government. This decision was in direct opposition to the Continental Congress’s orders to revise the Articles. However, it allowed the delegates to shift the powers away from the existing government and begin drafting the United States Constitution. States’ Plans Since the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention decided to throw out the Articles of Confederation, the floor was opened to suggestions for the basic structure of the new government. Edmund Randolph, representing Virginia, proposed a plan largely devised by James Madison. Madison, who felt that Randolph was a more powerful speaker and would be better able to gain support for the plan, suggested a bicameral, or two-house, legislature. This legislature would be charged with selecting a president of the United States as well as court officials for a federal judicial system. Under Virginia’s plan, population would drive representation, which would give larger states, such as Virginia, a distinct advantage over smaller states. Not surprisingly, delegates from smaller states resisted this plan. They feared that larger states, with their increased representation, would render the smaller states voiceless and ultimately meaningless. Representatives from the smaller states feared a loss of identity along with a loss of power if the Virginia Plan, or Large States Plan, was adopted. William Paterson, a delegate from New Jersey, developed an alternate plan, which would prevent the inequities of populous representation. The New Jersey Plan offered a unicameral Congress with each state having one vote. Under this plan, Congress would sit atop the governmental hierarchy with the most power, including the powers to tax and regulate trade. The executive and judicial branches would be separate from Congress and would not be as powerful. This plan closely resembled the unicameral government described in the Articles of Confederation. Just as representatives from smaller states fought against Virginia’s proposal, the delegates from larger states resented the restriction of power created by New Jersey’s suggestion. Delegates from the larger states felt that they should receive some acknowledgement of power based on their size. With the battle lines dividing the delegates based on state size, the Philadelphia Convention came to a standstill. The summer of 1787, Philadelphia was experiencing both a literal and a figurative heat wave, and the rising temperatures outside caused tempers to flare inside the Convention. Unproductive anger and debate created conflict that ironically only eased as the heat broke. As the weather became more comfortable, the delegates began to set aside their differences and consider compromises. Compromise Reigns The discord among the states’ delegates regarding the plans submitted by Virginia and New Jersey eventually subsided, and a negotiation—called the Great Compromise—for the new governmental structure was reached. This compromise was heavily promoted by Connecticut’s Roger Sherman, and the terms “Great Compromise” and “Connecticut Compromise” are used interchangeably. Under Sherman’s compromise, a bicameral legislature would combine elements of both Virginia’s and New Jersey’s plans to appease both the small and large states. With this plan, there would be two houses, initially called the “lower house” and the “upper house” due to their location in the twostory building that would house them. The lower house, which would become the House of Representatives, would be made up of a number of delegates based on each state’s population. These representatives were to be elected directly by the people. The upper house, which would become known as the Senate, would be limited to two delegates from each state. The election of senators would be carried out by the legislatures of each state. As a further compromise, it was agreed that all bills concerned with taxation and revenue would begin in the lower house. The Great Compromise also led to other important decisions about the government’s framework. In contrast to the long-standing fear of granting power to one sovereign authority figure, the Constitution gave the President a substantial amount of power. The President was granted the power to appoint officials, including judges, the power to veto legislation, and the role of Commander-In-Chief of the military. Defining the structure of the United States government was certainly a “Great Compromise,” but it was not the only compromise that made its way into the Constitution. Commerce regulations were also hotly debated. Northern industrial states wanted federal tariffs to keep out cheaper European products. By forcing the purchase of domestic goods, the Northern delegates hoped to raise revenues for the federal government through taxation. Those opposed to this idea included delegates from cotton and tobacco producing states, who relied heavily on trade with Europe and who resisted the idea of tariffs for exports. Furthermore, fearing unreasonable changes to trade regulations, these mostly Southern delegates asked for a two-thirds majority rule on all commerce bills in Congress. After much debate, a Commerce Compromise was reached that required no tax on exports, and only a simple majority needed to pass commerce bills through Congress. A third long-standing debate and eventual area of compromise at the Philadelphia Convention, questioned whether slaves should be counted as people or property. Although there was no intention of allowing slaves the same rights as free men, some argued that they should be counted as people to increase their states’ population count and thus the number of delegates in the lower house. Supporters of this school of thought were primarily Southerners who were eager for the power that their states would gain if the large number of slaves in the south were counted as people. Conversely, Northerners feared an increase in power by the south that might result from counting slaves as people. These delegates argued that slaves should be counted as property, and therefore taxed as such, since doing so could bring much-needed revenue to the federal government. Eventually, the delegates compromised on the slavery issue as well. Slaves were declared to count as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of population counts. However, neither the word slavery nor slave was used in the Constitution. Rather, it refers to the Three-Fifths Compromise as applying to “all other persons.” Still, it was apparent whom the Three-Fifths Compromise targeted, since it went a step further and addressed the issue of the African slave trade. Northerners expected the African slave trade to dwindle and eventually become unnecessary, and they wanted the Constitution to reflect that expectation. Southerners only knew that they had an immediate and ongoing need for slave labor in their fields and paddies, so they resisted slave trade restrictions. In addition to addressing the issues of population counts, the Three-Fifths Compromise stated that Congress would not restrict overseas slave trade for a period of twenty years, but following 1807 Congress was free to readdress the issue. In 1808, Congress did revisit the issue and decided to disallow overseas slave trade. By that point it was nearly moot since every state except Georgia had included an embargo on overseas slaves in their state constitutions. With the Great Compromise, Commerce Compromise, and the Three-Fifths Compromise in place, the proposed Constitution was ready to go to the states for ratification. http://www.apstudynotes.org