Lecture 18

advertisement

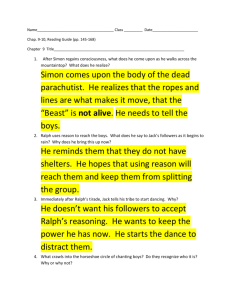

1 NOVEL II LECTURE 18 SYNOPSIS 2 Allegory Character analysis and critical discussion Allegory 3 The Lord of the Flies could be read as one big allegorical story. An allegory is a story with a symbolic level of meaning, where the characters and setting represent, well, other things, like political systems, religious figures, or philosophical viewpoints. Let's try a sample: 4 • • • • • The island represents the whole world. Ralph's conch-led Parliament represents democratic government. Jack's tribalism represents autocratic government. Piggy represents the forces of rationalism, science, and intellect—which get ignored at society's peril. Simon represents a kind of natural morality. 5 See how it's done? Of course, you could argue with this breakdown. Maybe Simon represents the religious side of humanity; maybe Jack represents cruelty, or maybe Roger does. But the point is that they're not fully developed and rounded characters so much as they are symbols. 6 The only time we pull out of the allegory is at the very end of the novel, when the other "real" world breaks through the imaginary barrier around the island. Yet this is also the moment when the real question of the allegory hits home: who will rescue the grownups? Body Paint 7 There's a reason (some) women put on more makeup when they're going on a job interview or a first date—and those neat-looking black stripes under football players' eyes are more effective at looking awesome than guarding against the sun. 8 Jack (duh) is the first one to pretty himself up, and he does it because he figures out that his pig-prey keeps spotting him: "They see me, I think," he says: "Something pink, under the trees" (4.2). And so he gets the bright idea to paint his face, "dazzle paint. Like things trying to look like something else" (4.24). 9 But the paint turns out to be more than camouflage. It doesn't just make Jack look like something else (say, part of the forest); it actually makes him into something else. It makes him into a savage—and then the chief. When his face is finished, "the mask was a thing of its own, behind which Jack hid, liberated from shame and self-consciousness" (4.34). With the paint on his face, Jack isn't choir-leader Jack anymore; he's a savage ready to be chief. 10 And Jack isn't the only one who has an inner savage. Eventually almost all the boys paint their faces, too. Ralph and his tiny band of still-civilized boys know that it's just paint, but that doesn't change its power. When they plan to go take Piggy's glasses back from Jack, Eric hesitates: "But they'll be painted! You know how it is." And everyone does: "They understand only too well the liberation into savagery that the concealing paint brought" (11.66). 11 So there you have it. Golding isn't being tricky with this symbol; paint "liberates" the boys into savagery, freeing them to act in a way that schools, parents, and policemen have never let them. In other words, the paint represents the savage within. It doesn't disguise the boys' true nature; it reveals it. Wounds 12 From the moment the boys land on the island, we begin to see signs of destruction. Over and over we are told of the "scar" that the plane leaves in the greenery (1.3). The water they bathe in is "warmer than blood" (1). The boys leave "gashes" in the trees when they travel (1). The lightning is a "bluewhite scar" and the thunder "the blow of a gigantic whip," later a "sulphurous explosion" (9). 13 If you're trying to answer the big question of whether the boys are violent by nature or are made violent by their unfortunate situation, you could argue that (1) because the island/nature is already so violent (think the thunder and lightning), the boys couldn't help but become part of its savagery when they arrived; or that (2) the boys are bringers of destruction, ruining the island paradise. Us? We'd like to go with option 1, but we're pretty sure Golding wants us to pick option 2. Characters… 14 Ralph Character Analysis Ralph is like the school president, football quarterback, and prom king all rolled into one, 12year-old package. He's the first lost boy we meet, and he's definitely the best—after all, he's elected chief. But what makes him chief-worthy? 15 Golden Boy Mostly, his all-American—we mean, all-British— good looks. He's "fair" (1.1) and "attractive." More than that, he has the conch. And he can blow it. Because the conch symbolizes power and order (see "Symbols" for more about that), Ralph gets a head start in the island power structure. 16 But he also knows what that power's for. Instead of getting caught up in the hunting bloodlust, he proposes something practical, sensible, and—we'll say it—British: start a fire, and then watch it to make sure it doesn't go out. He's got nerve, too. When someone has to go look for the "beast," Ralph appoints himself. When he's scared, he "[binds] himself together with his will" (7.246), meaning that he's able to force himself to do something he really, really doesn't want to do for the good of the group. Maybe He's Born With It 17 So, here's our question: is Ralph innately a good leader, or is he only a good leader as long as everyone agrees to live by "civilized" rules? Unfortunately for Ralph, it looks like his power depends on civilization. Check out how he approaches his office: "He lifted the conch. 'Seems to me we ought to have a chief to decide things' (1.228). A chief, to Ralph, is a sort of first-amongequals deal, someone who's elected to keep things in order. As he thinks, "if you [are] a chief, you [have] to think, you [have] to be wise […] you [have] to grab at a decision" (5.10). 18 See that word "decide" used twice? For Ralph, chiefdom is about leading people. It's not about personal power or triumph; it's about making sure the group is taken care of, which means making sure the little ones get looked after, keeping people from pooping where they eat (literally), and getting that darn fire lit. But is Ralph innately good? Maybe. He doesn't throw rocks at any little boys; he doesn't paint his face all crazy, and he insists that "this is a good island" (2). At the same time, our little golden boy isn't exactly innocent. 19 Decline and Fall One of Ralph's first actions is taking off his clothes. Believe us when we say that stripping is never a good sign: it's the first step to becoming a lawless savage. Here's how it goes down: 20 He [Ralph] jumped down from the terrace. The sand was thick over his black shoes and the heat hit him. He became conscious of the weight of clothes, kicked his shoes off fiercely and ripped off each stocking with its elastic garter in a single movement. Then he leapt back on the terrace, pulled off his shirt, and stood there among the skull-like coconuts with green shadows from the palms and forest sliding over his skin. He undid the snake-clasp of his belt, lugged off his shorts and pants, and stood there naked, looking at the dazzling beach and the water. (1.53) 21 Sure, this is probably a more sensible way to run around a deserted island than in black shoes and garters. But it's also a sign that, underneath his school uniform, Ralph is just as much a little savage as any of the other boys. We get a hint of this even earlier, when he "shriek[s] with laughter" about Piggy's name (1): Ralph may be a good kid, but he's still a kid. 22 And when it comes to hunting, Ralph starts to seem even more sinister. The first time he wounds a pig, he talks "excitedly" and thinks that maybe "hunting was good after all" (7). And then, when the party at Jack's starts to heat up, they find themselves "eager to take a place in this demented but partly secure society" (9)—which pretty soon turns into the brutal murder of Simon. No matter how much Ralph tries to convince himself that "we left early" (10), it's not true: he helped kill Simon. The beast lives in him, too. 23 Come to think of it, that just might be what saves him. At the end, he's all animal: he "launched himself like a cat; stabbed, snarling, with the spear, and the savage doubled up" (12.165), keeping himself alive long enough to roll away from Jack's band and end up at the feet of the naval officer—safe. For now. 24 Ch-ch-ch-changes We don't know what Ralph is going to be like now that he's back home, but we get the feeling he might be different. All that British order that he relied on? Now he knows that it's nothing more than a thin coating of civilization. Give him a sharpened stick and a pig carcass, and he's going to be ripping at the flesh with everyone else. 25 His first big philosophical moment comes during a late afternoon assembly, when the light makes everything look different. To Ralph, that means they are different: "If faces [are] different when lit from above or below— what is a face? What is anything?" (5.9) To translate: the island makes people lose their meaning. When the boys paint themselves and act like "savages," he decides they're completely different beings than the British boys who came to the island. To Ralph, this break in logic is a way of coping, a way of dealing with the horrors of his circumstances. But is he right? 26 Check out the way he gradually deteriorates over the course of the novel. As order and rules go by the wayside, so does the order within Ralph's own head. He can remember that he wants a signal fire, but he can't remember why. He knows it's something to do with smoke, but then he can't put two and two together. Piggy has to help him out repeatedly, and the gap in Ralph's train of thoughts worsens as the novel progresses. When they confront Jack and the "savages," Piggy has to remind him: "remember what we came for. The fire. My specs" (11.159). 27 Ralph remembers—but barely. And that just might make Ralph our tragic figure. Sure, Piggy and Simon both die. But Ralph is the one who has to go back to civilization with the knowledge that, underneath his schoolboy uniform, he's nothing more than a lawless, orderless savage. 28 Ralph Another perspective… Ralph is the athletic, charismatic protagonist of Lord of the Flies. Elected the leader of the boys at the beginning of the novel, Ralph is the primary representative of order, civilization, and productive leadership in the novel. While most of the other boys initially are concerned with playing, having fun, and avoiding work, Ralph sets about building huts and thinking of ways to maximize their chances of being rescued. For this reason, Ralph’s power and influence over the other boys are secure at the beginning of the novel. 29 However, as the group gradually succumbs to savage instincts over the course of the novel, Ralph’s position declines precipitously while Jack’s rises. Eventually, most of the boys except Piggy leave Ralph’s group for Jack’s, and Ralph is left alone to be hunted by Jack’s tribe. Ralph’s commitment to civilization and morality is strong, and his main wish is to be rescued and returned to the society of adults. In a sense, this strength gives Ralph a moral victory at the end of the novel, when he casts the Lord of the Flies to the ground and takes up the stake it is impaled on to defend himself against Jack’s hunters. 30 In the earlier parts of the novel, Ralph is unable to understand why the other boys would give in to base instincts of bloodlust and barbarism. The sight of the hunters chanting and dancing is baffling and distasteful to him. As the novel progresses, however, Ralph, like Simon, comes to understand that savagery exists within all the boys. Ralph remains determined not to let this savagery -overwhelm him, and only briefly does he consider joining Jack’s tribe in order to save himself. When Ralph hunts a boar for the first time, however, he experiences the exhilaration and thrill of bloodlust and violence. 31 When he attends Jack’s feast, he is swept away by the frenzy, dances on the edge of the group, and participates in the killing of Simon. This firsthand knowledge of the evil that exists within him, as within all human beings, is tragic for Ralph, and it plunges him into listless despair for a time. But this knowledge also enables him to cast down the Lord of the Flies at the end of the novel. Ralph’s story ends semitragically: although he is rescued and returned to civilization, when he sees the naval officer, he weeps with the burden of his new knowledge about the human capacity for evil. Jack 32 Jack Character Analysis For Jack, the island is like the best summer vacation ever. He gets to swear, play war games, hunt things, and paint his face—all without any grownups around to send him to his room for accidentally killing the neighbors. Like Ralph, Jack is charismatic and inclined to leadership. Unlike Ralph, he gets off on power and abuses his position above others—so, he's basically an '80s, without good hair and daddy's credit card. Let's see how he transforms from arrogant choir boy into painted savage. 33 Not-So-Golden Boy Jack is ugly. Well, according the narrator he is: he's "tall, thin, and bony: and his hair was red beneath the black cap. His face was crumpled and freckled, and ugly without silliness. Out of this face stared two light blue eyes, frustrated now, and turning, or ready to turn, to anger" (1). We've just met him, and we're already getting a bad feeling. Where Ralph is described as "fair" and "attractive," Jack is freckled and redheaded. (Duh, everyone knows redheads are evil.) And check out those angry eyes. It's no surprise that Jack can't wait to pick up a spear. 34 Ralph is elected leader because he's cute and seems pretty mature, and he's our protagonist for pretty much the same reasons. But Jack doesn't get it. He thinks that he deserves to be chief because he's "chapter chorister and head boy. [He] can sing C sharp" (1.228-30)—in other words, for no good reason at all. He should be leader because he's always been leader in the past, even though that leadership was based on something completely unrelated to his ability to govern: a nice singing voice. 35 The problem with this kind of social structure is that it's not based on anything real. At first, Jack seems ready to help Ralph establish order: "We've got to have rules and obey them. After all, we're not savages. We're English, and the English are best at everything" (2.192). That doesn't exactly sound like a kid who's five seconds away from slaughtering a wild pig and painting himself with its blood, right? 36 But saying "we have to have rules because we're English and awesome" is, when you think about it, identical to saying "I should be leader because I can sing C sharp." It's meaningless. It's jingoistic. And it disguises the fact that Jack is actually a pretty scary dude. As soon as there's no civilization to keep him in line, he—unlike Ralph—falls out of line. Majorly. 37 Power Corrupts Jack's litany of evil is pretty impressive. He leads the brutal slaughter of a pig—and then Simon. He fosters rebellion. He has his minions beat a kid named Wilfred for some unspecified misdeed. He throws a spear at Ralph with "full intention" (11), trying to kill him, and then sends the minions after him to finish the job. 38 But he couldn't do any of this without power. And somehow, he gets it. When he leaves Ralph's group, he convinces the others to come with him by promising a hunt. The pre-teen boys aren't interested in Ralph's boy-scout team-building and fire-watching. They want blood. And once Jack gets control, he turns from a choir boy into a, well, this: A great log had been dragged into the center of the lawn and Jack, painted and garlanded, sat there like an idol… Power lay in the brown swell of his forearms: authority sat on his shoulder and chattered in his ear like an ape. "All sit down." The boys ranged themselves in rows on the grass before him but Ralph and Piggy stayed a foot lower, standing on the soft sand. Jack ignored them for the moment, turned his mask down to the seated boys and pointed at them with his spear. (9.37, 52-56) 39 Jack is an "idol" with an "ape" sitting on his shoulder; he's no longer a little boy. He's a "chief," and not only the boys but the narrator actually calls him "the chief": "the chief was sitting there, naked to the waist, his face blocked out in white and red" (10). Jack? There is no Jack by this point. "Jack" is a just a name covering up the ugly, primitive core beneath the British choir boy exterior. When Jack picks up a spear and then walks out on Ralph's pitiful attempt to impose order, he's not a boy anymore: he's a savage. (And if you're thinking that this all sounds a little racist—we think you're right. 40 Kid Stuff By the end of the book, Jack has become a subhuman terror, inspiring panic in Ralph and awe in the rest of the boys. Or has he? Throughout the whole story, we get little hints that this might be nothing more than a game gone wrong. When Jack leaves Ralph's group, check how he does it: His voice trailed off. The hands that held the conch shook. He cleared his throat, and spoke loudly. "All right then." He laid the conch with great care in the grass at his feet. The humiliating tears were running from the corner of each eye. "I'm not going to play any longer. Not with you." (8.67-75) 41 Does this sound like a savage psychopath in the making, or does it sound like a little boy who's mad that things aren't fair? What's cool about this moment is that Golding mostly keeps us in the boys' viewpoint, and particularly Ralph's. When they're scared, we're scared; when they're having a fun pig-killing orgy, we're having a fun pig-killing orgy. But occasionally he drop in moments like this, where we see the boys in a new way—as kids playing a game gone horribly wrong. At the end, we see things from the naval officer's perspective. He asks who's in charge (assuming very Britishly that someone is), and Ralph steps up. Keep in mind that being in charge also means taking some sort of responsibility for, oh, the two gruesome murders. Maybe that's why Jack ends up hanging back: 42 A little boy who wore the remains of an extraordinary black cap on his red hair and who carried the remains of a pair of spectacles at his waist, started forward, then changed his mind and stood still. (12) To the boys, Jack is a powerful, savage chief. To the officer (and to us), he's just a "little boy" wearing goofy clothes. Golding leaves us with a question: what is Jack, really? Is he a heartless savage, or is he just a little British boy playing a game? Jack Another perspective… 43 The strong-willed, egomaniacal Jack is the novel’s primary representative of the instinct of savagery, violence, and the desire for power—in short, the antithesis of Ralph. From the beginning of the novel, Jack desires power above all other things. He is furious when he loses the election to Ralph and continually pushes the boundaries of his subordinate role in the group. Early on, Jack retains the sense of moral propriety and behavior that society instilled in him—in fact, in school, he was the leader of the choirboys. The first time he encounters a pig, he is unable to kill it. 44 But Jack soon becomes obsessed with hunting and devotes himself to the task, painting his face like a barbarian and giving himself over to bloodlust. The more savage Jack becomes, the more he is able to control the rest of the group. Indeed, apart from Ralph, Simon, and Piggy, the group largely follows Jack in casting off moral restraint and embracing violence and savagery. Jack’s love of authority and violence are intimately connected, as both enable him to feel powerful and exalted. By the end of the novel, Jack has learned to use the boys’ fear of the beast to control their behavior—a reminder of how religion and superstition can be manipulated as instruments of power. 45 Simon Character Analysis The first time we see Simon, he's fainting, and things go downhill from there. From passing out to throwing up to hallucinating to getting bloody noses, Simon is a walking mess. But he's anything but weak. 46 Power in All the Wrong Places Simon may be a little timid, but he's a compassionate guy. A "skinny, vivid boy" (1.267), Simon's innate goodness comes out in his actions. He recovers Piggy's glasses when they fly off his face (post-Jack's punch), he gives Piggy his own share of meat, and he helps the littluns pick fruit: "found for them the fruit they could not reach, pulled off the choicest from up in the foliage, passed them back down to the endless, outstretched hands (3.138). And, of course, he doesn't turn into a primitive savage and go around killing things. 47 He's also wise, mature, and insightful to the point of being prophetic. He's the only one (except Piggy) who understands the beast: Simon, walking in front of Ralph, felt a flicker of incredulity—a beast with claws that scratched, that sat on a mountain-top, that left no tracks and yet was not fast enough to catch Samneric. However Simon thought of the beast, there rose before his inward sight the picture of a human, at once heroic and sick. (6.140) 48 Simon, from his little leafy meditation cave, gets it: the island is changing them. Being afraid of the beast turns them into beasts. If you're having trouble understanding this, let's literalize it for you: he's basically saying that being afraid of an enemy makes you do such horrific things that you turn into the enemy yourself. And by "you," we mean "nations" and "governments." Sound familiar? It should. It's the same kind of argument that some people make today about the War on Terror. 49 Pig on a Stick But Simon's freaky wisdom doesn't mean he's immune to the island's effects. Hallucinating and probably dehydrated (that "swollen tongue" is a good giveaway [8.327]), he imagines—we think—the severed pig's head talking to him. And that means Simon is even wiser than we thought, because all of the head's lines are actually his own, like this: "Fancy thinking the beast was something you could hunt or kill! … You knew, didn't you? I'm part of you? Close, close, close. I'm the reason why it's no go? Why things are what they are?" (8.337) 50 Simon is the only boy to truly grasp that "the beast" is just all the negative, horrible aspects of mankind. And his "I'm the reason why it's no go" is a direct answer to the question Piggy posed several pages earlier: "What makes things break up the way they do?" (8.265). Simon does have all the answers—but no one's listening. Of course, there's also the remote possibility that the talking pig's head isn't a mere hallucination—it's the actual Lord of the Flies, evil incarnate, talking to Simon via a severed noggin. If this is true, Simon loses points for not coming up with the intelligent insights on his own. On the other hand, he gains quite a few points back for being like Jesus. 51 Christ Figure Yep, we've got a Christ-figure on our hands. To start with, his name is Simon, which happens to be the name of one of the twelve apostles. Simon started out as Simon until Jesus decided really his name should be "Peter" instead, because "peter" means rock—and Simon was the "rock" on which Jesus would build his church. If you glance at our "Nutshell," you'll notice that Lord of the Flies is a response to an earlier and much more cheerful boys-on-a-desert-island book, The Coral Island. Golding even borrowed the names Ralph, Jack, and Peterkin. Except "Peterkin" ended up as "Simon." 52 And then there's Simon's affinity for meditation, his kindred spirit-ness with animals, his attitude (think about the fruit-picking), and his ability to prophesize, like when he tells Ralph that Ralph will get home, and sort of suggests that he himself won't. 53 Having established that, we can go back to our pig'shead-on-a stick scene and compare it to Jesus's visit to the Garden of Gethsemene the night before he was crucified. And when we say "visit," what we really mean is long and solitary mental suffering, much like Simon undergoes the night before he meets his own untimely death. Simon, like Jesus, is "thirsty," and later "very thirsty," and although the text doesn't say it, we can only assume that at one point later he is very, very thirsty. He's also sweating, having a seizure, and bleeding profusely from his nose. 54 So, if Simon's "night before" matches up with Jesus's "night before," then does Simon die for the sins of the boys? Are they somehow saved by his death? It's hard to say. But it does seem meaningful that he alone had the knowledge of the beast's true nature, he alone had the potential to save the boys from themselves and their fear, and they basically kill him for trying to spread the good news. The tragic part (well, the especially tragic part) is that Simon says the beast is "only us" and then gets pegged as the beast himself—even though he's the least beastlike of any of the boys. The question is whether, like Jesus, being non-beasty makes him more or less human. 55 Simon Another perspective… Whereas Ralph and Jack stand at opposite ends of the spectrum between civilization and savagery, Simon stands on an entirely different plane from all the other boys. Simon embodies a kind of innate, spiritual human goodness that is deeply connected with nature and, in its own way, as primal as Jack’s evil. The other boys abandon moral behavior as soon as civilization is no longer there to impose it upon them. They are not innately moral; rather, the adult world—the threat of punishment for misdeeds—has conditioned them to act morally. 56 To an extent, even the seemingly civilized Ralph and Piggy are products of social conditioning, as we see when they participate in the hunt-dance. In Golding’s view, the human impulse toward civilization is not as deeply rooted as the human impulse toward savagery. Unlike all the other boys on the island, Simon acts morally not out of guilt or shame but because he believes in the inherent value of morality. 57 He behaves kindly toward the younger children, and he is the first to realize the problem posed by the beast and the Lord of the Flies—that is, that the monster on the island is not a real, physical beast but rather a savagery that lurks within each human being. The sow’s head on the stake symbolizes this idea, as we see in Simon’s vision of the head speaking to him. Ultimately, this idea of the inherent evil within each human being stands as the moral conclusion and central problem of the novel. Against this idea of evil, Simon represents a contrary idea of essential human goodness. However, his brutal murder at the hands of the other boys indicates the scarcity of that good amid an overwhelming abundance of evil. REVIEW 18 58 Allegory Character analysis and critical discussion