Examining the *Real* American GI of World War II Europe

advertisement

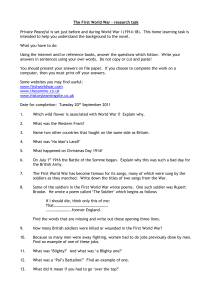

Morales 0 Examining the “Real” American GI of World War II Europe Alejandro Morales Morales 1 Examining the “Real” American GI of World War II Europe On June 6th 1944, sub-lieutenant Jimmy Green was onboard a LCA (Landing craft Assault) 910 headed to Omaha beach. On his way to the beach he passes by a column of LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks), the very same tanks that were suppose to pave the way for the landing troops. Green and everyone else on board decided to move on because they were suppose to land at 6:30 am with the rest of the 116th 1st battalion. When they landed, they arrived at an untouched beach guarded by a walled array of pillboxes.1 Less than 50 yards away, Sergeant Thomas Valance’s landing craft lowers its ramp and his platoon move forward to the beach maneuvering through knee high waves. As he tries to find balance, a bullet penetrates his palm. The wound feels like a sting and in a surge of adrenaline he moves forward throwing behind his heavy equipment. He stops to fire at the pillboxes and one returns fire and hits his left thigh breaking his hipbone. All around him soldiers trying to make their way to the beach are pinned down. Others trying to swim ashore are drowned by their heavy equipment or are picked off by enemy fire.2 The wounded sergeant still 1 Pill Boxes are concrete dug-in guard posts Alex Kershaw, The Bedford Boys: One American Town’s Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice (Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2003), 127- 139 2 Morales 2 moves forward, only now he crawls to the sea wall. He collapses and later writes: “I was one live body amongst many of my friends who were dead and, in many cases, blown to pieces.” 3 Thomas Valence was one of many soldiers that marched through Germany to help take down the Nazi regime. Stories reporting the heroics of troops sensationalized the American GI as a good-mannered American patriot who went on this crusade to preserve democracy. Images like “Iwo Jima” or “The Manly GI” (See Figures 1.1 and 1.2) presented the troops as liberators only heightening their status in the American folklore. However the American soldier action’s overseas showed no sign of respect or morality. While the United States held its troops as heroes and saviors due to the type of media coverage, European civilians thought of GIs as thieves, racists, drunks and even rapists. These soldiers paid the ultimate sacrifice but it’s not fair to ignore the shame and devastation they left behind. In France, Soldiers were to blame for the high rates of rape and prostitution that brought shame to the country. As they advanced through Germany, the GIs looted and displaced families in attempt to find alcohol or anything of value. In addition, the harsh treatment of “colored” also shows how little respect GIs showed to neither their enemies nor allies.4 Ronald Drez, Voices of D-Day: the story of the Allied Invasion Told by those who Were There (London: Luisana State University Press, 1994) 201-202 4 Michael C. C. Adams, The Best War Ever America and World War II (Baltimore, MA:John Hopkins University Press, 1994); Christopher P Loss, “Reading between Enemy Lines: Armed Services Editions and World War II.” Journal of Military History, Vol. 67, No. 3 (Jul., 2003): 811- 834; Alford, Kenneth, The Spoils of World War II: The American Military's Role in the Stealing of Europe's Treasures. (New York, N.Y.: Carol Pub. Group, 1994); Arthur Coleman and Hildy Heel, Great Stories of World War II: An Annotated bibliography of Eyewitness War-Related Books Written and Published Between 1940 and 1946 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2007); Seth Givens. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” War In History, 33-54; Arnold T, The 92nd Infantry Division and reinforcements in World War II, 1942-1945. (Washington, DC: Sunflower University Press, 1991); Virden, Jenel. "Warm Beer and Cold Canons: US Army Chaplains and Alcohol Consumption in World War II." Journal Of American Studies 48, no. 1 (February 2014): 79-97; Drea Edward, “American Soldiers: Ground Combat in the World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam.” Journal of American History 90.3 (2008); Melissa Block. “Interview: Fred Bornet recounts his World War II experiences,” All Things Considered (NPR) (n.d.): Newspaper Source; John McManus, "Deadly 3 Morales 3 In order to understand the real GIs and the role they played in the war, some historical context must be shined on the events. World War II began where WWI ended, in Versailles. When the allies met in Versailles, the consensus was that Germany had to pay for the war. When Germany signed the treaty, it agreed to take all blame from the war, to pay 6,600 million pounds in reparations, to demilitarize its army and lastly to relinquish 25,000 square miles of Germany territory. The defeated German people felt cheated by the deal and no one shared this sentiment more than the Adolf Hitler. The new Weimar Republic came to power at the end of the war oversaw that the Germany pay their reparations costs. Throughout the 1920’s Germany stayed afloat thanks to the Dawes Act, which allowed Germany to borrow 800 million marks from the US. Unfortunately, the Stock Market crashed in 1929 and this took its toll on Germany. In 1932, a third of its workforce was unemployed and the Weimar Republic could do nothing to help its people. Adolf Hitler used this devastation to get ahead in the political sphere along with his new Nazi Party. In 1930, the Nazi Party won 18% but by the beginning of January 1933, Hitler had been appointed Chancellor of Germany. Immediately after getting power, Hitler began to plan for war as he oversaw the expansion of the German army and navy. This violation of the treaty went unnoticed and the rest of Europe watched as Hitler began to mobilize is troops. From 1936- 1939, Brotherhood: The American Combat Soldier in World War II." (PhD diss., The University of Tennessee, 1996), 1-40; Sam Lebovic, “’A breath from Home”: Soldier Entertainment and the Nationalist Politics of Pop Culture during World War II,” Journal of Social History Vol. 47 Issue 2 (December 2013): 263-296; Mary Louis Roberts, What Soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France (London, The University of Chicago Press, 2013); L. Jooste, “The Unkown Force; Black, Indian and Coloured Soldiers Through Two World Wars,” South African Journal of Military Studies (2012); Harry Spiller, American POW’s in World War II: Twelve Personal Accounts of Captivity by Germany and Japan (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2009); Thomas Bruscino, “The Analogue of Work: Memory and Motivation for Second World War US Soldiers,” War & Society Vol. 28 Issue 2 (October 2009): 85-103 Morales 4 Europe stood silent as Hitler and his new army absorbed Austria and the Rhineland. In 1938, when the Hitler wanted to take back the Sudetenland, Neville Chamberlin entered negotiations with the intent to prevent the outbreak of war. Chamberlin argued that the Versailles treaty was too harsh and rather than risking war, he appeased Hitler and let him take the 99% German populated Sudetenland. Chamberlin landed in Europe claiming that he had assured peace foe his time. However, in 1939 Hitler went on to invade the rest of Czechoslovakia. In response to this, England and France finally decided that if Germany were to invade Poland, they would go to war. Germany invades Poland on September 31st, 1939, thus beginning the 2nd World War. However on the western hemisphere, the United States tried to stay away from the troubles of Europe. At the end of WWI, the US decides not to join the League of Nations and went into a state of isolationism. However the US was inclined to peek at the pacific as it saw the rise of the Japanese state. The Japanese were in deep financial problems and to solve it they needed to expand their military. In 1931, the Japanese army attacked and occupied the southern region of Manchuria. The American Government responded to the invasion by cautioning the Japanese that any further aggression would result in the cutoff of shipments and raw materials. That did little to persuade the Japanese government as they decide to leave the League of Nations and formed an alliance with Adolf Hitler in the fall of 1940. The deal with the growing threat of Japan in Manchuria, the United States supported the Chinese with the gift of army and equipment. As the Japan marched further into Indo-China, European nations had enough of the Japanese aggression and cut off any flow of sources to the nation. Realizing that their conquest could not go on without supplies, they devised a scheme to take control of the Oil-rich British Malaysia Morales 5 and East Indies. Knowing that the United States would not stand for this, the Japanese army devised a plan to take out the American presence in the pacific. On December 7th 1941, the Japanese army did the unthinkable and bombed Pearl Harbor. Not only did they bomb Pearl Harbor, the Japanese forces subdued the American presence in the pacific by taking over their bases in Guam, the Philippines and British Malaysia. The attack outraged the American public and the very next day, President Roosevelt declared war on Japan and Germany. If an effort to maintain high morale at home, reporters wrote pieces sensationalizing the GI. On July 13, 1943 a New York Times article titled “The Paratroopers” praised the newly formed paratroopers after they had recently gone to combat in Sicily. Before the writer concludes, he describes the new paratroopers as “good natured joking boys proved(ing) that a democracy could be tough when the toughness is required.”5 This report on paratroopers only helped build up the GI. By presenting a story of American troopers diving into the battlefield of planes, the author only built the perception that the American soldier was brave and ready to defend democracy. Stories like this one would ease the public back home because it offered them security in the belief that their troops will do anything to preserve democracy. Like the writer of “The Paratroopers,” reporters at the time were well aware that their reports should not only aim to report on events, but also to give Americans a sense that all was good on the war front. In response to this resorted to writing about “dangerous escapes and close encounters 5 "The Paratroopers." New York Times, Jul 13, 1943. 20 Morales 6 with the enemy.”6 The story of was one of many whose war stories became widely known in the states. On the meadows of Cherbourg Lieutenant Rebarcheck led “125 Americans to Victory Over 300 Germans.”7 The Lieutenant leaped over three tanks and dodged an array of machine gun fire and secured a heavily fortified enemy strong point. This overdramatized battle report was one of many that aimed to boost morale. It made civilians admire the patriotism of their American troops. On the contrary, many soldiers wanted the war to be over with and hopefully make it home in one piece.8 More importantly, they denied and hated the idea that they fought for a greater cause. Soldier Russell Stoup wrote a letter home describing crowds of soldiers leaving a movie called In Which We Serve displeased with it. Stoup justified their displeasure with the movie by writing “'it concerned the war, which they don't like to see, and it was filled with patriotic sentiment, which is anathema. This isn't just a lack of patriotic fervor: it's actual hatred of anything that suggests it. They fall for all sorts of cheap sentiment, except that one.”9 Soldiers could not stand the topic of patriotism because they weren’t patriots. They also hated the fact that media romanticized their service in the military, but this was due to the actions the military would take on any media who wrote negative press. The fact of the matter is that these soldiers were involved in all sorts of horrible acts such as stealing from civilians or even raping a French girl, yet they weren’t reported. Buljung, Brianna. "From the Foxhole: American Newsmen and the Reporting of World War II." International Social Science Review 86, no. 1/2: 44-64. 7 "LIEUTENANT A HERO IN CHERBOURG Push." New York Times, Jun 29, 1944. 4 8 Bruscino, Jr., Thomas, "The Analogue of Work: Memory and Motivation for Second World War US Soldiers." War & Society 28, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 85 9 Bruscino, Jr., Thomas, "The Analogue of Work: Memory and Motivation for Second World War US Soldiers." War & Society 28, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 86 6 Morales 7 Fred Bornet served as a combat cameraman in World War II filming War-front Movies. He was also journalist so he kept a black journal recounting his time in the war. In his interview with Melissa Block, he shared a passage recounting filming a girl in the ruins of the Italian town of Cassino: “later on, by Aquafondata(ph), bare feet in the mud, her hair matted with rain, standing alone in front of the giant wheel of a GMC truck, crying, `(Foreign language spoken).' And my camera would grind relentlessly, catching the heartbreak. And the child would stare straight into the lens, her gaze burning through the glass, darkly, desperately, as if to say, `Why? Why are you doing this?” 10 This excerpt from Bornet’s journal touches more on the devastation of the war itself and it would never get published. Reports like these would only rile up the home front against the war. This excerpt presents more context of the devastation of the war by presenting a sincere retelling of an uncomfortable event. Bornet’s journal entry differs greatly from what was usually reported about the war. Typical newspapers and popular culture portrayed courageous soldiers with the aim to raise support for the war. Bornet’s passage would never get published because instead of raising support of the war, the scene would highlight the horrors of war and make the American public turn against the war effort. The Office of Censorship stressed that the disclosure of vital information would help the enemy country.11 If a reporter failed to follow these rules “The Office of Censorship was prepared to complain to the appropriate newspaper or radio station Block, Melissa. “Interview: Fred Bornet recounts his World War II experiences.” Interview by Melissa Block All Things Considered 11 Steele, Richard W. "News of the 'Good War' World War II News Management." Journalism Quarterly 62, no. 4 (Winter 1985): 707-783. 10 Morales 8 owners, or to publicize the recalcitrant and presumptively unpatriotic behavior.”12 The creation of the OFC shows that the federal government was wary of the American public turning on the war. The US was founded on the notion of freedom of speech and freedom of the press. So what happened? What did they want to control? The American GI grew up hearing tales of romantic adventures from their fathers who served in WWI which lead to myths that France was land of “wine, women and song.”13 After liberating France, many Americans were free to live out these romantic adventures that in turn stories that resulted in cases of rape and prostitution, the spread of venereal diseases and tensions with the French. The photograph titled the “Manly GI” (See Image 1.2) shows an American GI cuddling up to a couple of French girls. Images like these were used as propaganda to bolster the idea that the Americans were the saviors. On September 1944, General Charles H. Gerhardt ordered the creation of a prostitution house outside St. Renan. Unfortunately, it was shut down after five hours of business.14 This was one of many brothels that popped up all over France. At one point in France, it became apparent that the “spectacle of sex was the price paid by the French for American discretion.”15 Sexual relations between soldiers and French civilians became more common and in some cases, soldiers would even have sex in broad daylight. In the French town of Reims, authorities received many letters from mothers concerned with the influx of prostitutes to the city. There were reports of prostitutes being “accosted” on the Roberts, Mary Louise, What soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II (Chicago, MI: The University of Chicago Press) 1 14 Roberts, Mary Louise. “The Price of Discretion: Prostitution, Venereal Disease and the American Military in France.” American Historical Review 115, no. 4 (October 2010): 1002 15 Roberts, Mary Louise. “The Price of Discretion: Prostitution, Venereal Disease and the American Military in France.” American Historical Review 115, no. 4 (October 2010): 1010 13 Morales 9 streets in the presence of children. The local hotels could not house all the prostitutes that came to the city of Le Havre. This caused prostitutes to set up their businesses in local parks and cemeteries. 16 The French people were horrified by the debauchery that became of their towns. This only fueled resentment towards American troops. This influx of prostitutes in turn not only resulted in the rise of venereal disease but most importantly increased tensions between the French and troops because American Military wasn’t necessarily worried about their soldiers engaging in sexual relations with French civilians. Pierre Voisin, the mayor of Le Havre reached to the American military to help deal with the prostitutes and proposed that the military create a restricted zone far from the public eye. The restricted zones would contain tents left for prostitutes and GI. The restricted area would have to be guarded by police and medical personnel. Col T.J. Weed responded to Voisin’s proposal by making it clear that the mayor had and should handle the matter on his own and second that the daunting task of transporting soldiers in and out of the city was more important. This response to Mayor Voisin points out that the military did not care about the huge impact its soldiers where having on the city. Instead, the army cared more about limiting the spread of venereal disease to its troops because it threatened the “endurance of the troops.” The army issued GIs condoms in order to prevent the spread of venereal disease. Responding to high rates of venereal disease, on December 1943, Commander Jacob Devers wrote to all soldiers: “the loss of manpower from venereal Disease cannot be excused. Each soldier who contracts venereal disease betrays the United States as completely as one who willfully neglects his duty.”17 The Roberts, Mary Louise, What soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II (Chicago, MI: The University of Chicago Press) 188 17 Roberts, Mary Louise, What soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II (Chicago, MI: The University of Chicago Press) 163 16 Morales 10 commander echoes the idea that the health of the American soldier was more important then anything else because the war effort depended on the strength of the American troopers. The military’s worry over the health of their boys lead to the tensions with the nations they were saving. The French grew tired of the troops for example: when “the locals sold the troops “dishonest bottles of wine.” The GIs countered by throwing from their vehicles, in answer to begging cries for cigarettes and candies, used and ripe old condoms, “filled,” said one soldier, “with our drainings (Paul Fussell Pg 40).”” 18As one can see there was a clear division between the GI and the French people. France was “A country that means nothing to us,” boasted GI Mitchell Sharpe. The rest of the military felt the very same sentiment. The American troops had no respect for France or its citizens. Even after the Americans sailed home, prostitutes stayed in the city of Le Havre and by January of 1946, Prostitutes sickly with venereal wards filled the expensive clinics that the port had set up for them. The events that occurred in port Le Havre reflect the Military’s inability to take responsibility of for the devastation it caused France. More so then that, American troops defiled and disrespected the French people. In “Warm beer and Cold Cannons: US Army Chaplains and Alcohol Consumption in World War II,” Jenel Virden explores alcoholism in American camps during world war II Europe.19 She drew most her assertions from the view point of Chaplains (a member of the church who works for a branch of the armed forces), who believed that exposure to alcohol in camps would only result in the increase of drinking Paul Fussell. The Boy’s Crusade: The American Infantry in Northwester Europe (New York, The Modern Library): 40 19 Virden, Jenel. "Warm Beer and Cold Canons: US Army Chaplains and Alcohol Consumption in World War II." Journal Of American Studies 48, no. 1 (February 2014): 82 18 Morales 11 habits after the war. Though religion may play huge part in their sentiment towards drinking in camps, the author makes a good point that there was a huge worry about drinking in camps. At that time, prohibition had recently been abolished; so many of the young boys who went overseas were in a free environment where beer and alcohol was made readily available to them. Especially in times of war, soldiers used alcohol to relax and get away from the harsh realities of the war. In some cases soldiers seeking alcoholic beverages would go to great extremes to get drunk. Bootleg alcoholic drinks like “Jungle Juice”, were really popular in training camps. From January to July, Bootleg Methyl (wood) alcohol accounted for the death of 188 GIs in 1945.20 The army itself failed to control the consumption of alcohol because it provided soldiers with beer and alcohol by allowing the sale of alcoholic products in camps. In essence, the American army didn’t do much to keep their troops from consuming alcoholic drinks. Not only that, many of these instances were barely reported. The consumption of alcohol during the war resulted in soldiers coming home alcoholics. Many of these soldiers would take their drinking habits back home thus influencing an already changing drinking culture in Post-World War II America. In addition, the army’s reluctance to control drinking had an effect on the way they behaved during the war. The first thing soldiers looked for when arriving to new towns were bars and breweries. If there wasn’t a brewery, soldiers like David Webster figured that “wine, beer, and all blends and ages of hard liquor were available for the Virden, Jenel. "Warm Beer and Cold Canons: US Army Chaplains and Alcohol Consumption in World War II." 90 20 Morales 12 asking in almost every house and Bierstube (was) within short driving range.” 21 Webster’s proposal to take alcohol from civilians brings into light the GIs willingness to steal from civilians. It shows that soldiers were more preoccupied with their own needs. The GIs had no problem stealing for the German people. The article, “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War,” writes that American GIs felt that looting in Germany was “morally and legally justifiable.”22 Americans justified their looting in Germany because they felt that German people is getting what they truly deserve. Looting is “justifiable” and “moral” because the Germans started this war and soldiers like private first class Richard Courtney felt they were “giving the Germans a taste of what they have doing to others for years.”23 Such sentiments show that the American GI held a really strong animosity towards the Germans. Soldiers essentially got their revenge on Germany by stealing from its people. These acts of revenge just go to show that the American GI weren’t the moral liberators publicized by local media. In some cases American troops would search buildings and remove owners from their properties just so GIs would have somewhere to spend the night. In the German town of Kassel, man from Patton’s third army reportedly entered a civilian home and searched it before they ordered the German family to pack their belongings and take refuge in their cellars.24 (Givens 36) As one can see soldiers didn’t just loot homes, but they also confiscated them. This shows that the GI was not afraid of Givens, Seth. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” War In History no. 1(January, 2014): 39 22 Givens, Seth. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” War 33-55. 23 Givens, Seth. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” 34 24 Givens, Seth. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” 36 21 Morales 13 taking advantage of German people. It shows that they were not a moral. Although American troops looted for alcohol or a “quick buck,” the main reason American troops felt this was acceptable was because they used looting as a way to punish the German people for their atrocities. American society at the time segregated, and nowhere was this more evident than in the American military. Most African Americans were assigned to service and supply, which reflects the transfer of ideas such as segregation and racism from American society to overseas.25 Not only that, there are little accounts of the contribution of minorities during World War II, because most the reports were written by white officers who often “excluded, limited, or misreported African-American soldier’s contributions.”26 The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 prohibited discrimination by race or color in recruitment but it didn’t stop the segregation of black soldiers who were assigned to the most menial jobs. One of the big misconceptions about the American military in World War II was the notion that the African American soldier could not hold jobs of authority such as pilots and officers. African American veteran William H. Thomas recollects an incident in Tuscany where he and other African American soldiers were banned from attending a beautiful resort that they had helped liberate. Not only that, the most shocking part was that the order came directly from an American general in charge that did not want black soldiers to attend the resort.27 This is only one of many times cases where superior officers put down their colored troops. On October 6 1644, the US chief of McGuire, Phillip. “Judge Hastie, World war II and Army Racism.” Journal of Negro History 62, no.4 (October 1977): 351-362. 26 Black, Helen. “A War Within a War: A World War II Buffalo Soldier's Story.” Journal of Men’s Studies 20, no. 1 (January 2012): 36 27 Black, Helen. “A War Within a War: A World War II Buffalo Soldier's Story.” 40 25 Morales 14 police in the ETO (European theater of operations) met with the marshal to present a list of crimes that the soldiers were charged for. The report listed rape as the top offense. The report stated that 152 GIs were being tried for rape and of these 139 of them were colored troops. 28 Although the colored GI was only 10% of all troops there, the report makes it obvious that mostly “colored” troops were being tried and charged for rape. However In the town of Cheltenham, its civilians grew angry at the treatment of black soldiers. The townspeople were given the title of “nigger lovers,” because they favored black soldiers. A woman working a troop canteen echoed that belief when she stated “we find the colored troops nicer to deal with. We like serving them; they are always so courteous and have a very natural charm that’s most of the white miss. Candidly, I’d far rather serve a regiment of dusky lads than a couple of whites.” 29 From the incident in Cheltentelham to the opinion of bar attendant, it’s evident that racism was very prevalent in the army. It became apparent that the black GI found no comfort in its own army as soldiers and even higher-ranking officers felt that they could mistreat and disrespect their own American comrades. It’s important to understand that the American military went to great lengths to censor the actions of their troops. The American military tried hard to control their soldiers, but it’s quite evident that they had a hard time doing so. The real American soldier that took down the Nazi Regime was just as flawed as any other guy. The soldiers who fought in World War II were not the courageous characters that movies and Roberts, Mary Louise, What soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II 195 Paul Fussell. The Boy’s Crusade: The American Infantry in Northwester Europe (New York, The Modern Library): 22 28 29 Morales 15 newspapers wanted to exploit. In trying to exploit the courageous deeds of the American soldier, we have created this false image of the “Good War” which saw as much horror and indecency as any other war. The idea of the “Good War” was developed in order to generate civilian support of the war. This notion worked so well that many civilians at home felt like their contributions matched those of the foot soldiers in Europe. 30 Most importantly, one must understand that the Good War is a great example of collective memory. The real question is, who is the real American GI? Its become quite evident that the American soldier is not the hero movies and media presented. The real American GI is a man with flaws. The American army command stood motionless as its soldiers engaged in sexual relations that showed very little respect to the French people. More than that, the American soldier had little regard for laws of the army because he looted allied territories and simultaneously drank dangerous amounts of alcohol, which put him and others in danger. Another problem with the American army was the relevance of segregation and Jim Crow laws, which worked well to omit the contributions and stories of African American soldiers. The “Good War” tried to omit many of the flaws of the American military in Europe. In omitting these negative aspects of the war, we present a flawed interpretation of the army that has been popularized by lack of reports on the negative activities of American GIs. Michael C. C. Adams, The Best War Ever America and World War II (Baltimore, MA: John Hopkins University Press, 1994) 30 Morales 16 Annotated Bibliography I. Primary Sources Block, Melissa. “Interview: Fred Bornet recounts his World War II experiences.” Interview by Melissa Block All Things Considered In this interview, Fred Bornet talks about his experiences in World War II as a combat cameraman. He shares excerpts from a journal that kept during the war. "The Paratroopers." New York Times, Jul 13, 1943. 20 This was a newspaper article that talked about the new paratrooper division that were just formed and went into action. The writer praised the boys for their heroism as they went on their first mission to Sicily. “Lieutenant a Hero in Cherbourg Push." New York Times, Jun 29, 1944 This newspaper article tells the story of an American GI named Lieutenant John C. Rebarcheck. The lieutenant and his GIs successfully captured an armored position in the meadows of Cherbourg. II. Secondary Sources Adams C. C. Michael, The Best War Ever America and World War II (Baltimore, MA: John Hopkins University Press, 1994) In this book, Michael Adams takes down the myth of the “good war.” He challenges many assumptions of the period to and shines light on what really happened in the war Black, Helen. “A War Within a War: A World War II Buffalo Soldier's Story.” Journal of Men’s Studies 20, no. 1 (January 2012) Helen black chronicles the experience William H. Thompson as an African American GI in World War 2. Since white officers wrote most accounts of the war, Black wants to explore how racism in the war affected them and how they dealt with it from the words of African American GIs. Bruscino, Jr., Thomas, "The Analogue of Work: Memory and Motivation for Second World War US Soldiers." War & Society 28, no. 2 (Fall 2009) Bruscino’s article touches on the motivations of men who fought in American wars. In this article makes distinctions between the soldiers who fought in the wars and their motivations to go on these crusades. Morales 17 Buljung, Brianna. "From the Foxhole: American Newsmen and the Reporting of World War II." International Social Science Review 86, no. 1/2: 44-64. Buljung’s take on censorship highlights that the journalist of WW2 had to write articles boosting public morale. She also talks about how drastically censorship has change over time. She concludes that modern reporting with less censorship has contributed to the loss of support for military operations. Drez Ronald, Voices of D-Day: the story of the Allied Invasion Told by those who Were There (London: Luisana State University Press, 1994) 201-202 In this book, Paul Fussell’s writes about the unforgettable experiences of American infantryman in World War 2. Based on the author’s own experiences, it tells a narrative from the point of view of a childe because the soldiers that went to war were just that. Through this narration, he wants to debunk the myths of the war and bring more attention to the brutality of the war. Givens, Seth. “Liberating the Germans: The US Army and Looting in Germany during the Second World War.” War 33-55. In this article, Seth Givens explores the many reasons GIs looted Germany. He draws from memoirs, letters, and troops to justify why soldiers committed these crimes. He also elaborates on how the American army reacted to these crimes and what steps they made to eradicate looting. Kershaw, The Bedford Boys: One American Town’s Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice (Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2003), 127- 139 Based on extensive interviews with survivors and relatives, as well as diaries and letters, Kershaw's book focuses on telling the story of one small American town that went to war and died on Omaha Beach. McGuire, Phillip. “Judge Hastie, World war II and Army Racism.” Journal of Negro History 62, no.4 (October 1977): 351-362. This article narrates the story of William H. Hastie who was the aid to the Secretary of War. McGuire writes about how Hastie’s recommendations on black equality helped bring some much needed changes to the military in terms of race. Steele, Richard W. "News of the 'Good War' World War II News Management." Journalism Quarterly 62, no. 4 (Winter 1985): 707-783. Focuses on the news management used by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II in the U.S. Creation of an Office for Censorship to encourage cooperation of the press; Objective of the censorship to prevent publication of information useful to the enemy; Function of newsreels in conveying the everyday meaning of the war to the American people. Morales 18 Roberts, Mary Louise, What soldiers do: Sex and the American GI in World War II (Chicago, MI: The University of Chicago Press) In this book, Roberts tells of the story of the French people who were disrespected by the GIs who liberated them. She sheds light on the American soldier’s fault in the rise in prostitution and rape of French women. Virden, Jenel. "Warm Beer and Cold Canons: US Army Chaplains and Alcohol Consumption in World War II." Journal Of American Studies 48, no. 1 (February 2014) Jenel explores the issue of alcohol in camps from the point of view of military Chaplains. Chaplains at the time were alarmed by the alcohol binges they saw around them because they worried of the effects of alcohol on the morality of the soldiers. This article chronicles the difficulties of military chaplain’ s who attempted to save their “flocks.”