The Development Impact of New Zealand's RSE Seasonal

advertisement

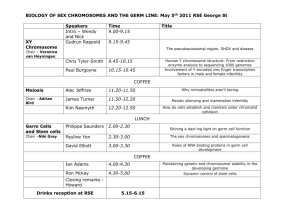

David McKenzie, World Bank (with John Gibson) Temporary migration programs seen as offering a “triple-win” – good for migrants, the sending country, and the receiving country. Seasonal workers are the largest single temporary migration category in the OECD. Remain controversial – with critics arguing that workers will overstay, compete down wages of native workers, and that workers may be exploited or not earn enough to make short-term migration worthwhile. What is lacking is evidence on development impacts. Launched in 2007 with the dual goals of aiding economic development in the Pacific Islands while easing labor shortages in New Zealand’s horticulture and viticulture industries. Designed taking account of lessons from other countries, and now seen as possible model policy. E.g. ILO good practices database states ◦ “The comprehensive approach of the RSE scheme towards filling labour shortages in the horticulture and viticulture industries in New Zealand and the system of checks to ensure that the migration process is orderly, fair, and circular could service as a model for other destination countries.” “First and foremost it will help alleviate poverty directly by providing jobs for rural and outer island workers who often lack income-generating work. The earnings they send home will support families, help pay for education and health, and sometimes provide capital for those wanting to start a small business”. Winston Peters, New Zealand Minister of Foreign Affairs, at the approval of the RSE program, October 2006. The Evolution of the RSE Program Over 5000 workers recruited in first 15 months (to June 2008) • • 4000 from Pacific, 1000 from Others (SE Asia) quota then increased to 8000 per year • • total 2nd season almost met the new quota down slightly in third year partly due to effects of the recession on NZ labour market • at the same time, Australian pilot scheme announced in Aug 2008 and started in Feb 2009 has recruited just over 100 workers • RSE Quota Quota of 5000 (now 8000) seasonal workers, allowed to come for maximum of 7 months in 11 month period. Work in horticulture and viticulture. Workers can return again in next season Several mechanisms to low risk of workers overstaying – overstay rate <1% Mostly male workers >80% Multi-year prospective evaluation launched alongside the roll-out of the policy. Close collaboration between World Bank, New Zealand Government, and Governments in Tonga and Vanuatu. Conducted baseline surveys of over 450 households (>2000 individuals) in Tonga and Vanuatu before workers left ◦ Sample contains households with workers selected for RSE, households where workers applied but not selected, and non-applicant households. Then follow-up surveys of these same households at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after RSE program had begun Two largest suppliers of RSE workers Vanuatu Tonga Samoa Solomons Tuvalu Kiribati NonPacific Substantial difference between the two in previous migration experience ◦ Different recruitment approaches ◦ High emigration from Tonga almost none from Vanuatu Government-led, pro-poor in Tonga, private sector in Vanuatu These differences should increase the external validity of extrapolating from our results to other contexts Tonga -- “negative selection” on income ◦ RSE workers drawn from households in the poorer parts of the income distribution Any positive household-level impacts likely to be pro-poor Samoa – “neutral selectivity” ◦ RSE workers drawn from households whose income appears indistinguishable from average households (relying on a retrospective comparison) Vanuatu – “positive selection” ◦ RSE workers drawn from richer households *after year 1 for Samoa Tonga -- low in terms of lost wages at least ◦ Very few (8%) RSE workers in wage employment prior to leaving for work in New Zealand Remaining family mainly need to replace a home production contribution rather than a cash contribution Samoa – moderate ◦ One fifth of RSE workers employed prior to going to New Zealand (Based on first six months of 2007 rather than six months prior to leaving for NZ) Vanuatu – higher ◦ Two-fifths of sampled RSE workers had been employed prior to leaving for New Zealand *Unconditional average over all (both employed and unemployed) who became RSE workers 12 Panel difference-in-differences and panel fixed effects models after trimming sample to households with propensity scores in the range [0.1, 0.9] Surveys contain rich data and many of elements which lead matching to be more successful ◦ Same questionnaire given to treatment and control at same point in time from same labor markets ◦ Have good knowledge of the characteristics which affect both supply and demand side of participation and can control for them. ◦ Ask retrospective earnings history, so can match on more than one pre-treatment period of earnings. ◦ Natural reason why some people migrated and others with similar characteristics did not – there was excess demand for RSE employment, so not all households who wanted to participate could do so. Match on: PS-1: - household demographic variables pre-RSE - characteristics of the 18-50 year old males (english literacy, education, health, alcohol use) - household’s previous experience and network in New Zealand - Household baseline assets and housing - Geography (island) - Wage and Salary history PS-2: all this plus whether they applied to work in RSE. Difference-in-differences Specification 4 𝑌𝑖,𝑡 = 𝛼 + 𝛽𝐸𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑅𝑆𝐸𝑖 + 𝛿𝑡 + 𝛾𝑅𝑆𝐸𝑖,𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑡 𝑡=2 Fixed Effects Specification: 4 𝑌𝑖,𝑡 = 𝜇𝑖 + 𝛿𝑡 + 𝛾𝑅𝑆𝐸𝑖,𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑡 𝑡=2 Two measures of exposure to policy: - Ever work in New Zealand in RSE by time t - Cumulative number of months in RSE at time t The exposure to the ‘treatment’ varied widely 0.14 Tonga 0.12 Vanuatu Cumulative duration of RSE months worked at wave 4 of our survey • duration ranges from 1 RSE month to over 20 RSE months 0.08 Density variation due to variable spell lengths, only some workers having multiple spells and a few households with multiple workers • 0.1 0.06 0.04 • 0.02 0 0 5 10 15 Months 20 25 Remarkably low attrition in Tonga ◦ Only 1% per round (sample sizes 448 in round 1, 442 in round 2, 444 in round 3, 440 in round 4). Higher attrition in Vanuatu ◦ 10-15% per round, but not cumulative since rounds 3 and 4 also tried to track baseline households not in round 2 ◦ Sample sizes 456 in round 1, 382 in round 2, 388 in round 3, 348 in round 4. ◦ Slightly higher among non-RSE households ◦ Partly due to mobility of individuals amongst extended family and lower cost residential mobility Greater reliance on informal/shanty housing in urban settlements in Vanuatu than in Tonga More difficult to track households over survey rounds Appendix shows main results are robust to bounding approaches to deal with this attrition. 40 participating in RSE Percentage Increase from 45 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Income -DD Income -FE Tonga Expenditure -DD Vanuatu Expenditure -FE Table 2: Average Impact of RSE Migration on Household Income and Expenditure in Tonga Difference-in-Differences Fixed Effects Baseline Mean (1) (2) (3) (5) (6) Outcome Variable: for RSE households All PS-1 PS-2 All PS-1 PANEL A: IMPACT OF EVER BEING IN THE RSE Per Capita Income 979 331.0*** 278.4*** 233.1* 347.4*** 271.0*** 248.7** Log per Capita Income 6.57 0.355*** Per Capita Expenditure 829 224.1** 127.1 Log per Capita Expenditure 6.58 0.124** PANEL B: IMPACT PER MONTH'S DURATION IN RSE Per Capita Income 979 24.56*** 0.346*** 0.290*** (7) PS-2 0.383*** 0.355*** 0.324*** 104.6 249.8** 117.8* 133.0 0.117** 0.0834 0.128*** 0.0926* 0.0900 23.49** 20.03* 39.48*** 35.06*** 31.19*** Log per Capita Income 6.57 Per Capita Expenditure 829 9.765 3.476 -0.126 15.78 2.632 1.170 Log per Capita Expenditure 6.58 0.00257 0.00227 -0.00178 0.00339 -0.00106 -0.00277 1,774 448 1,499 379 1,092 274 1,774 448 1,499 379 1,092 274 Number of Observations Number of Households 0.0326*** 0.0350*** 0.0329*** 0.0459*** 0.0469*** 0.0449*** Table 3: Average Impact of RSE Migration on Household Income and Expenditure in Vanuatu Difference-in-Differences Fixed Effects Baseline Mean (1) (2) (3) (5) (6) (7) Outcome Variable: for RSE households All PS-1 PS-2 All PS-1 PS-2 PANEL A: IMPACT OF EVER BEING IN THE RSE Per Capita Income 85282 42,861*** 44,441*** 48,241*** 29,522* 32,760** 37,717** Log per Capita Income 10.73 Per Capita Expenditure 65872 Log per Capita Expenditure 10.63 0.320*** 0.301*** 0.364*** 0.186* 0.167 0.267** 12,353** 13,020** 1,093 2,228 2,978 0.240*** 0.261*** 0.254*** 0.134* 0.137* 0.132* 3,391 5,066** 5,964** 8,495 PANEL B: IMPACT PER MONTH'S DURATION IN RSE Per Capita Income 85282 3,382* Log per Capita Income 10.73 Per Capita Expenditure 65872 Log per Capita Expenditure 10.63 Number of Observations Number of Households 4,992** 5,219** 0.0366*** 0.0466*** 0.0501*** 0.0284** 0.0364*** 0.0488*** 1,006 2,225** 2,023** 660.3 1,531** 1,504** 0.0233** 0.0351*** 0.0321*** 0.0162* 0.0258** 0.0236** 1,574 456 1,225 360 977 269 1,574 456 1,225 360 977 269 Results show a 31-42 percent increase in income per capita over the 2 years for the average household participating in the RSE This makes it one of, if not the most, successful development intervention for which rigorous impact evaluation is available: ◦ Progresa/Oportunidades – only 8 percent increase in per capita expenditure, and this involved handing out lots of money ◦ Microfinance – recent Spandana randomized trial by Banerjee et al. finds no impact on average income. But migrants earned NZ$12,000 in NZ, compared to baseline household incomes of $NZ1400 per capita in Tonga and NZ$2500 per capita in Vanuatu. So if you can earn 5-7 times per capita income, why is increase “only” 30-40%? ◦ 1) Migrants have costs in NZ and of airfare, so amount remitted + repatriated = NZ$5,500. ◦ 2) This increase is only for one individual per household. Since average household is 5-6 members, this makes PER CAPITA increase around NZ$1,100. ◦ 3) Only half the households went for 2 years, so average per capita increase over 2 years requires dividing by 1.5 ◦ 4) Then households face opportunity cost in terms of what migrant would have done at home. Imagine a 10-step ladder, where on the bottom step were the poorest people and the top step the richest people, state which step of the ladder they thought their household was on today, and on which step their household was on two years ago. We find 0.43 step increase in Tonga and 0.65-0.77 increase in Vanuatu – approximately 0.5 standard deviation increase in both countries. Find Tongan households 10-11 percentage points more likely to have improved dwelling over 2 years if in RSE. Vanuatu 6-7 percentage points more likely. Households with Bank account: 10-14 percentage point increase in Tonga from RSE, 17-19 percentage point increase in Vanuatu Tongan RSE households are significantly more likely to have acquired a cellphone, television, DVD player, and bicycle over the two-year period than similar non-RSE households. RSE households also seem to have sold their kerosene ovens and purchased gas or electric ovens instead. The ni-Vanuatu RSE households are significantly more likely to have acquired a radio or stereo, a DVD player, a computer, a gas or electric oven and a boat over the two-year period than similar non-RSE households. - School fees identified as one of most important uses of money earned -Find a 10-14 percentage point increase in proportion of 16-18 year olds attending school in Tonga; no significant effect in Vanuatu -Not much non-farm self-employment Relatively modest – villages got about $500 in remittances to village on average – used in Tonga mostly to improve water supply. In Tonga 92 percent of leaders say that it has had positive effects after two years, and in Vanuatu, even at 6 months, 72 percent of leaders say the overall impact is positive. RSE designed with promoting development in the Pacific as an explicit goal. We find it has largely met this goal. Results make seasonal migration one of the most cost-effective and largest impact development interventions for which rigorous evidence available Caveats: ◦ Impacts may change over longer-term ◦ Gains still pale in comparison to permanent migration ◦ Open question how far one can extrapolate to other country contexts, but scale and best-practice procedures along with large baseline differences between Tonga and Vanuatu suggest reasonable external validity.